Abstract

Study design: Descriptive study.

Objective: To describe the demographics, cause of injury, and annual-paid medical costs for the 5 years following injury for cases of work-related tetraplegia.

Setting: A single United States workers' compensation (WC) claims database.

Methods: Tetraplegia cases with initial date of injury from 1 January 1989 to 31 December 1999 were selected by cross-referencing word search terms pertaining to body part injured and nature of injury. The main outcome measures were injury causes and annual-paid medical payments (adjusted to year 2000 medical consumer price index) of work-related tetraplegia by injury group for each year postinjury over a 5-year time period.

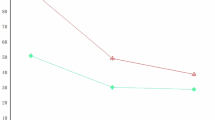

Results: A total of 62 claimants with work-related tetraplegia injured between 1 January 1989 and 31 December 1999. The vast majority of those identified were male claimants (92%) and more than a quarter worked in the construction industry (26%). Other highly represented industries included transportation and retail (15% each), manufacturing (13%), and agriculture and utility (11% each). The majority of injuries were the result of falls (36%) and vehicular accidents (34%). The mean Year 1 cost was $560 524 for those with a high-level tetraplegia (C2–4 ASIA A–C), $431 033 for a low-level injury (C5–8 ASIA A–C), and $178 041 for those with an ASIA D tetraplegia injury. The mean cost of subsequent years (Years 2–5) was $130 992 for a high-level, $129 250 for a low-level, and $34 352 for an ASIA D tetraplegia injury.

Conclusions: Mean costs for Year 1 postinjury in WC cases are similar to previously published estimates. Comparing the current results with those of previous spinal cord injury cost studies suggests that those with work-related tetraplegia may receive more injury-related paid medical benefits after the first year postinjury than cases who do not receive WC-supported benefits.

Sponsorship: Supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDDR) (Grant # H133N00024).

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal cord injury: facts and figures at a glance. J Spin Cord Med 2001; 24: 212–213.

DeVivo MJ, Whiteneck GG, Charles ED . The economic impact of spinal cord injury. In: Stover SL, DeLisa JA, Whiteneck GG (eds). Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Outcomes from the Model Systems. Aspen Publishers: Gaithersburg, MD 1995, pp 234–271.

Cifu DX, Seel RT, Kreutzer JS, McKinley WO . A multicenter investigation of age-related differences in lengths of stay, hospitalization charges, and outcomes for a matched tetraplegia sample. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 733–740.

DeVivo MJ et al. Trends in spinal cord injury demographics and treatment outcomes between 1973 and 1986. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992; 73: 424–430.

DeVivo MJ . Causes and costs of spinal cord injury in the United States. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 809–813.

Price C, Makintubee S, Herndon W, Istre GR . Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury and acute hospitalization and rehabilitation charges for spinal cord injuries in Oklahoma, 1988–1990. Am J Epidemiol 1994; 139: 37–47.

Johnson RL, Brooks CA, Whiteneck GG . Cost of spinal cord injury in a population-based registry. Spinal Cord 1996; 34: 470–480.

Menter RR et al. Impairment, disability, handicap and medical expenses of persons aging with spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1991; 29: 613–619.

Harvey C et al. New estimates of the direct costs of traumatic spinal cord injuries: results of a nationwide survey. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 834–850.

Webb SB, Berzins E, Wingardner TS, Lorenzi ME . First year hospitalization costs for the spinal cord injured patient. Paraplegia 1977–1978; 15: 311–318.

US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Lost-Worktime Injuries: Characteristics and Resulting Time Away from Work, 2000 (USDL02-196). [http://stats.bls.gov/oshome.htm, Series Id: CDU00013X3N] Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office 2000.

Tate DG, Forchheimer M, Daugherty J, Maynard F . Determining differences in post discharge outcomes among catastrophically and noncastrophically sponsored outpatients with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1994; 73: 89–97.

American Spinal Injury Association. International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI ASIA. Chicago: American Spinal Injury Association 2000.

American Medical Association. Physicians' Current Procedural Terminology. CPT 2001. Chicago: American Medical Association 2000.

US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index – All Urban Consumers, US City Average, Medical Care, Series Id: CUUR0000SAM. Available from URL: http://data.bls.gov/servlet/SurveyOutputServlet.

Tabachnick B, Fidell L . Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd edn. New York (NY): Harper Collins 1996.

US Census Bureau. Geographic Areas Reference Manual. http://www.census.gov/geo/www/garm.html.

Rosenberg NL, Gerhart K, Whiteneck G . Occupational spinal cord injury: demographic and etiologic differences from non-occupational injuries. Neurology 1993; 43: 1385–1388.

Fullerton HN . Evaluating the 1995 labor projections. Monthly Labor Rev 1997; 5–9.

US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Lost-worktime Injuries and Illnesses: Characteristics and Resulting Time Away From Work, 2000. [USDL 02-196] Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office 2002. Also available from URL: http://stats.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/case/osnr0015.pdf.

US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, Series Id: LFU11106000001 and LFU11106000000. Available from URL: http://www.bls.gov/data/.

US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, Series Id: LFU1132015800001 and LFU1132015800000. Available from URL: http://www.bls.gov/data/.

Tate DG, Forchheimer M, Daugherty J, Maynard F . Insurance benefits coverage for persons with spinal cord injuries: determining differences across payers. J Am Paraplegia Soc 1993; 16: 76–80.

Berkowitz M et al. The Economic Consequences of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. New York (NY): Demos Publications 1992.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Jamil Ahmed, Radha Vijayakumar, Ashar Ata, and Santosh Verma for their assistance in data collection. We also acknowledge Russell Hensel for his technical assistance, and Helen Wellman, Rammahon Maikala, and Jon Mukand for their review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Webster, B., Giunti, G., Young, A. et al. Work-related tetraplegia: cause of injury and annual medical costs. Spinal Cord 42, 240–247 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101526

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101526

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Work-related traumatic spinal cord lesions in Chile, a 20-year epidemiological analysis

Spinal Cord (2011)

-

Rehospitalization following compensable work-related tetraplegia

Spinal Cord (2006)

-

Services provided following compensable work-related tetraplegia

Spinal Cord (2004)