Key Points

-

A high proportion of patients will not fully understand the consent to treatment even when adequate information has been provided.

-

Sufficient time should be given for patients to consider the disclosed information to allow them to understand the treatment procedure better.

-

Consent should be repeated before carrying out the actual treatment especially if some time has elapsed since signing the consent form and the actual time of treatment.

Abstract

Objective To determine whether parents of children attending the outpatient general anaesthesia (OPGA) session at the Eastman Dental Hospital, London fully understand the proposed treatment.

Design Observational study supported by structured questionnaires and interviews.

Setting Casualty service in the Department of Paediatric Dentistry and the Victor Goldman Unit (a day-stay general anaesthetic unit) of the Eastman Dental Hospital.

Main outcome measures The parents' understanding of the consent was assessed based on their knowledge of the actual treatment procedure, the type of anaesthesia to be used and the number and type of teeth that would be extracted.

Results Fifty-two of the 70 subjects (74%) approached completed both parts of the survey (interviews one and two). Results showed that 40% of the written consent obtained from the parents were not valid. The subjects' knowledge of the proposed treatment improved on the day of the actual treatment although 19% of them still did not fully understand the procedure. There was a statistically significant increase in the proportion of valid consent on the day of the actual treatment. Many of the subjects had no knowledge of the type of anaesthesia that would be used for their children but were more aware of the number and type of teeth that were going to be extracted. The time interval between the consent process and the actual treatment did not have any significant effect on the subjects' understanding of the consent, but it implied that with time the subjects' knowledge improved.

Conclusion A proportion of subjects did not fully understand the proposed treatment procedure even after being adequately informed. Appropriate measures should be taken to ensure that the patients or their guardians truly understand the proposed treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Rozovsky LE . Imposing your will upon the patient. The temptation can have legal consequences. Oral Health 1986; 76: 51–53.

Etchells E, Sharpe G, Walsh P, Williams JR, Singer PA . Bioethics for clinicians: 1. Consent. Can Med Assoc J 1996; 155: 177–180.

Bailey BL . Informed consent in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 1985; 110: 709–713.

St Clair T . Informed consent in pediatric dentistry. A comprehensive overview. Pediatr Dent 1995; 17: 90–97.

Mitchell J . A fundamental problem of consent. Br Med J 1995; 310: 43–48.

Doyal L, Cannell H . Informed consent and the practice of good dentistry. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 454–460.

Maintaining Standards. Guidance to dentists on professional and personal conduct 1997 Amended 1999 London: General Dental Council; Consent 3.7.

Hagan PP, Hagan JP, Fields HW, Machen JB . The legal status of informed consent for behaviour management techniques in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent 1984; 6: 204–208.

Consent to Treatment revised by J Gilberthorpe London; Medical Defence Union 1996 p 5.

Advice Sheet B1. Ethics in Dentistry London; British Dental Association 1995: 49–53.

Cassileth BR, Zupkis RV, Sutton-Smith K, March V . Informed consent – Why are its goals imperfectly realized? N Engl J Med 1980; 302: 896–900.

Waisel DB, Truog RD . Informed Consent. Anesthesiol 1997; 87: 968–978.

Family Law Reform Act (1969) Section 8(1). The Public General Acts and Church Assembly Measures 1969; Part I. Chapter 46: 997–1021 London: HMSO.

Worthington LM, Flynn PJ, Strunin L . Death in the dental chair: an avoidable catastrophe? (Editorial). Br J Anaesth 1998; 80: 131–132.

Lavelle-Jones C, Byrne DJ, Rice P, Cuschieri A . Factors affecting quality of informed consent. Br Med J 1993; 306: 8859–8890.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed Tahir, M., Mason, C. & Hind, V. Informed consent: optimism versus reality. Br Dent J 193, 221–224 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801529

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801529

This article is cited by

-

Ambulante zahnärztliche Behandlung von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Allgemeinanästhesie

Oralprophylaxe & Kinderzahnheilkunde (2022)

-

Exploring how newly qualified dentists perceive certain legal and ethical issues in view of the GDC standards

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Mothers’ perceptions of their child’s enrollment in a randomized clinical trial: Poor understanding, vulnerability and contradictory feelings

BMC Medical Ethics (2013)

-

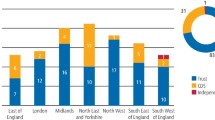

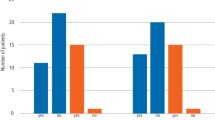

An audit of the level of knowledge and understanding of informed consent amongst consultant orthodontists in England, Wales and Northern Ireland

British Dental Journal (2008)

-

How informed is informed consent?

British Dental Journal (2002)