Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here

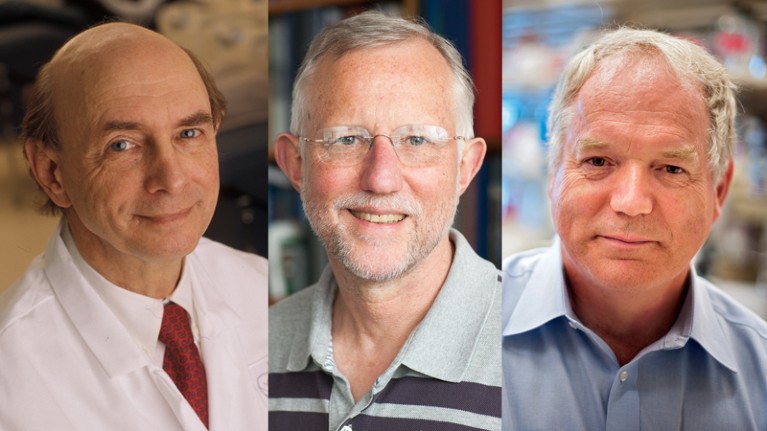

Harvey Alter, Charles Rice and Michael Houghton (left to right) won the 2020 Nobel prize in medicine for their research on the hepatitis C virus.Credit: NIH History Office, John Abbott/The Rockefeller University, Richard Siemens/University of Alberta

Hepatitis C scientists win medicine Nobel

A trio of scientists who identified and characterized hepatitis C — the virus that is responsible for many cases of hepatitis and liver disease — are the recipients of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology of Medicine. Harvey Alter, Michael Houghton and Charles Rice share the award. “It stands out as an emblem of great science,” says Ellie Barnes, who studies liver medicine and immunology. “We’ve got to a point where we can cure most people who are infected.”

Houghton has turned down high-profile awards because they didn’t acknowledge his collaborators, George Quo and Qui-Lim Choo. “It’s all based on the Nobel prize,” explained Houghton in 2013. “In his will, Dr. Nobel says there can be no more than three. All of the other major awards tend to copy that and limit it to three. It’s antiquated.”

Nature | 5 min read & National Post | 5 min read (from 2013)

Life on Venus: the truth is up there

Researchers are racing to confirm the surprise discovery of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus — and investigate whether it really could indicate the presence of life. Astronomers propose using NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii and its telescope-on-a-plane, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy. And three space missions are scheduled to fly close to Venus in the coming months: Europe and Japan’s BepiColombo spacecraft — on its way to Mercury — and the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter and NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, both travelling to the Sun. There is also a spacecraft currently orbiting Venus: Japan’s Akatsuki mission, which can’t spot phosphine directly but can investigate the atmosphere and the clouds. And India, the United States and Europe are planning future missions.

Read more: Possible sign of life on Venus stirs up heated debate (National Geographic | 11 min read)

Last chance for WIMPs

Researchers are pushing to build a final generation of supersensitive detectors — or one ‘ultimate’ detector — that will leave an elusive dark-matter candidate with no place to hide. For decades, physicists have hypothesized that weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) are the strongest candidate, but several experiments have failed to turn up any evidence for them. Over the coming months, operations will begin at three existing underground detectors — in the United States, Italy and China — that search for dark-matter particles by looking for interactions in supercooled vats of xenon. If that doesn’t do the job, researchers will look to rival WIMP detectors that use materials such as germanium and argon. Or perhaps an even more powerful xenon detector, which would be so sensitive that they would reach the ‘neutrino floor’ — a natural limit beyond which dark matter would interact so little with xenon nuclei that its detection would be clouded by neutrinos.

Features & opinion

Form a ‘journal club’ for equity in science

A group of early-career researchers that meets regularly to discuss inequalities in science and society share their tips to start your own gathering. They use a journal-club format in which they discuss a book, set of articles, podcast or movie (often a documentary). “But unlike journal clubs, which often focus on critiquing the work being discussed, we use the materials to launch examinations of ourselves, each other, our departments and our institution at large,” writes the group.

How science really works

As a young biology student, Joshua Rothman discovered that science “was two-faced: simultaneously thrilling and tedious, all-encompassing and narrow. And yet this was clearly an asset, not a flaw”. Now a writer and editor, Rothman reviews a new book by philosopher Michael Strevens that aims to identify the special something that drives science’s countless successes. The practice of science “channels hope, anger, envy, ambition, resentment—all the fires fuming in the human heart—to one end,” argues Strevens. “The production of empirical evidence.”