Source research: Hermansen, A. S. et al. Immigrant–native pay gap driven by lack of access to high-paying jobs. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09259-6 (2025).

Messages for policy

• Prioritize initiatives to improve immigrants’ access to high-paying positions. Equal-pay policies are important, but closing the pay gap requires greater access.

• Invest in language training, education and vocational skills to improve access to quality employment.

• Early access to employment information, networks, job-search assistance and employer referral can reduce mismatches in job placement.

• Standardized and transparent recognition of foreign degrees and credentials could help immigrants to access jobs that match their skills and training.

• Employer bias in hiring and promotion practices contributes to job segregation. Improved organizational transparency and managerial accountability can counteract this issue.

The policy problem

Differences in earning levels between immigrants to high-income nations and people born there persist even after accounting for education and other human-capital characteristics. These disparities remain despite long-standing integration efforts and anti-discrimination legislation1.

Designing effective responses requires a clear understanding of what drives these gaps. Do pay differences arise because immigrants are paid less than people born in that country who do the same work for the same employer (that is, within-job pay inequality) or because they are concentrated in low-paying jobs and labour-market sectors? Each mechanism requires a distinct policy response2–5: one would target unfair wage-setting; the other, barriers to better-paid employment.

Identifying the relative contributions of unequal job access and within-job pay inequality is therefore crucial for designing effective policies to narrow the pay gap between nationals and migrants, and to expand economic opportunities for immigrant workforces.

The findings

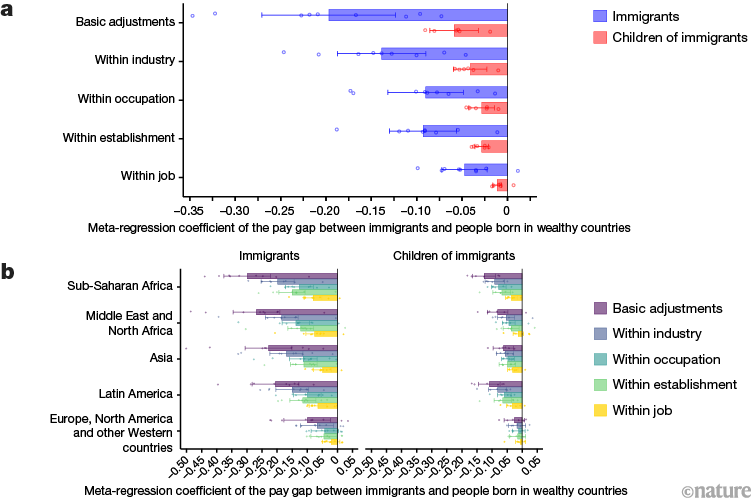

We show that earning gaps are driven mainly by differences in the types of job that immigrants hold, and to a lesser extent by unequal pay for equal work (Fig. 1a). Looking across nine European and North American countries, we find that, on average, three-quarters of the gap reflects immigrants’ under-representation in high-paying occupations and firms, whereas one-quarter is due to differences in pay for the same role at the same workplace. These patterns hold across countries with diverse labour-market structures and immigration histories. Immigrants from Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and Asia are affected more than are those from Europe and North America (Fig. 1b), but the dominant role of access to high-paying jobs is consistent across regions of origin. Both the overall gap and within-job inequality are smaller among children of immigrants born in wealthy nations, showing that disparities narrow as barriers — such as language skills and credential recognition — are reduced.

Figure 1 | Earnings gaps between immigrants to nine high-income countries and people born there. Earning gaps between immigrants and individuals born in one of nine wealthy countries (Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the United States) after basic adjustments (age, sex, education and region of employment) and comparing workers in the same industry, occupation, establishment and job (that is, with unique combinations of occupations and workplaces). a, Average gaps for all immigrants. b, Average gaps separated by immigrants’ region of origin. The results are obtained from a meta-analysis of country-specific estimates of the differences in earnings, in log-transformed annual earnings. Overlaid dots represent country-specific differences for each comparison. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals and the line at zero represents the reference category (people born in the analysed nations).Credit: Hermansen, A. S. et al./Nature (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

The study

We used administrative records that link employees to employers for 13.5 million workers across Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the United States. These records provide information on workers’ earnings, occupations and employers, enabling direct comparisons between immigrant employees and people born in that country who have the same occupation at the same workplace. We documented how much of the pay gap arises from individuals in the same job receiving different salaries as opposed to arising from immigrants being concentrated in low-paying industries, occupations and establishments.

Our comparative design spanned countries with diverse labour-market institutions and immigration histories, enhancing the generalizability of the findings. The results highlight the central role of job sorting in shaping immigrant labour-market disparities and underscore the importance of addressing structural barriers to ensure that immigrants can fully contribute to their host country’s economy.

Read the paper: Immigrant–native pay gap driven by lack of access to high-paying jobs

Read the paper: Immigrant–native pay gap driven by lack of access to high-paying jobs

Encounters with inequality lead to demands for taxes on the rich

Encounters with inequality lead to demands for taxes on the rich

Racial bias eliminated when ratings switch from five stars to thumbs up or down

Racial bias eliminated when ratings switch from five stars to thumbs up or down