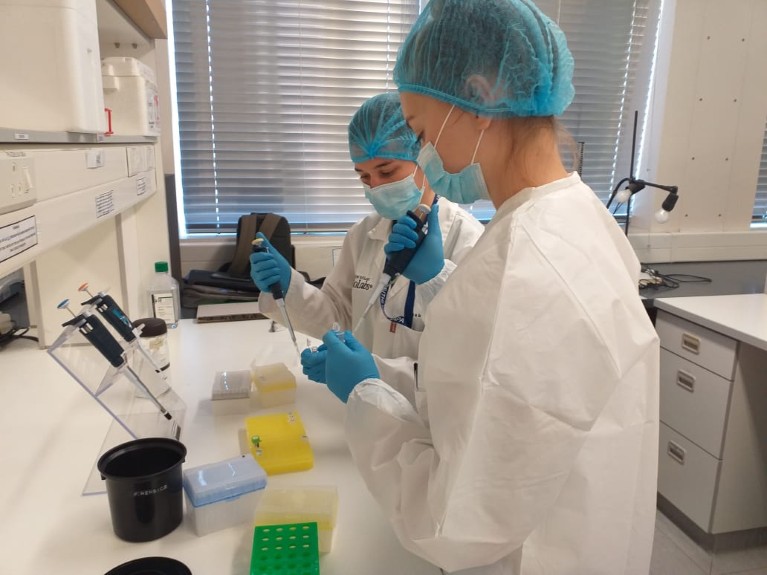

Caption: At work in Laura Heathfield’s lab.Credit: Laura Heathfield

In South Africa, where thousands of people who have died remain unidentified each year, and cause-of-death records are far from complete, Laura Heathfield is offering a powerful tool for accuracy and closure: DNA.

Based at the University of Cape Town (UCT), Heathfield is contributing to the development of molecular autopsy research, an approach to post-mortem analysis that uses genetic testing to answer questions traditional autopsies can’t. While traditional DNA forensics matches samples to known relatives, molecular autopsies delve into the genetic causes of sudden, unexplained deaths, particularly in infants and young people, by sequencing multiple genes linked to inherited conditions.

Heathfield’s efforts were recently awarded South Africa’s prestigious NRF P-rating, a distinction given to promising young researchers by South Africa’s National Research Foundation. But for her, this recognition is more than personal. “I hope it brings attention to Africa’s urgent forensic and humanitarian challenges and drives real investment into solutions,” she says.

Unidentified, unclaimed, unresolved

Two of the most critical forensic science challenges in Africa today are unidentified remains and unexplained deaths, especially in infants. South Africa’s high level of unidentified remains is driven by several overlapping challenges from lack of a centralised missing persons data base and mass migration and porous borders — especially from neighbouring countries — to limited access to ante-mortem DNA or dental records in undocumented people.

“I’ve seen hundreds of nameless bodies in our mortuaries and countless infant deaths with no clear cause of death,” says Heathfield “This work is about restoring dignity to the dead and giving families the answers they deserve.”

Her research has already led to real-world breakthroughs. In one case, she discovered a lethal genetic mutation in a deceased baby, a mutation that would have allowed the surviving twin to be treated, had it been caught earlier. “That case reminds me why this work matters beyond the science,” she says. “It’s about saving lives and preventing repeated tragedies.”

The first forensic exome panel of its kind in Africa

Heathfield’s current research is a custom forensic exome panel designed specifically for post-mortem use in African populations. Unlike hospital-based genetic tests, a custom forensic exome panel is a genetic testing tool that targets selected regions of the exome— the protein-coding portion of the human genome.

With state-of-the-art facilities at UCT and the Western Cape’s Forensic Pathology Services, including Africa’s first MiSeq FGx sequencing platform, installed in 2018, which enables high-resolution forensic DNA sequencing even from degraded samples which are vital for post-mortem analysis.

Heathfield is pushing the boundaries of DNA technology in forensic settings. “We’re moving from analysing single genes to scanning entire panels, all from biological material collected from a deceased person that has been damaged or degraded,” she says.

Ethical research practices in African mortuaries are evolving as Heathfield collaborates with forensic teams in Namibia, Botswana, and Kenya, sharing ethical frameworks and protocols developed in Cape Town. In some cases, post-mortem bone and tooth samples are sent to her lab for analysis; in others, she advises on establishing local capacity and runs training workshops across the continent..

“The volume of forensic casework that come in can overwhelm the police or the state’s forensic services, leaving little time for advanced DNA analyses and exploration of new technologies and research. Additionally, it appears that many studies in a post-mortem forensic setting globally use additional samples taken at autopsy for research without the informed consent of the next of kin,” she explains.

In Cape Town, she developed a framework to conduct post-mortem genetic research ethically and responsibly, a model that is now being used by forensic teams across South Africa. “I want informed consent and engagement with next of kin to become the norm,” she says.

Training Africa’s next generation of DNA detectives

Heathfield has supervised more than 85 postgraduate students and co-authored numerous high-impact papers. She’s also sounding the alarm about the state of forensic education. “Too many students skip the core sciences for flashy forensic courses,” she warns. “Master the science first then apply it to the forensic world.”

She envisions a future where African forensic labs are proactive, equipped to deliver answers that are scientifically sound, ethically gathered, and socially transformative. This means generating African-specific DNA data, guiding investigations in real time, and shaping national policy on unidentified remains and sudden deaths.

By using DNA to discover why people died, rather than just who they were, Heathfield is helping rewrite the script of forensic science in Africa, one gene at a time.