Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Socioeconomic disparities in diet are well documented, but the relative importance of different indicators of socioeconomic position (SEP) is not well known. The aim of this study was to explore relationships between food patterns, SEP (occupation, education and income) and degree of work control.

Subjects/Methods:

A cross-sectional population-based study 2000–2001, using three self-administered questionnaires including food frequency questions (FFQs). Factor analysis was used to explore food patterns. Participants include 9762 working Oslo citizens, 30–60 years of age, having answered the questionnaires with <20% of the FFQ missing.

Results:

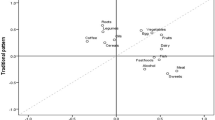

Four food patterns were found: Western, prudent, traditional and sweet. In multivariate analyses, the likelihood of having a high intake of the Western pattern was lowest in the two highest educational groups (women: odds ratio (OR)=0.54/OR=0.75; men: OR=0.51/OR=0.76), and in the two highest occupational groups for men (OR=0.73/OR=0.78). The odds of having a high intake of the prudent pattern was highest in the two highest educational groups (women: OR=2.50/OR=1.84; men: OR=2.23/OR=1.37), and among the self-employed (women OR=1.61, men OR=1.68), as well as in the highest occupational group for men (OR=1.33). Women always having work control were least likely to have high intake of the Western pattern (OR=0.78) and most likely to have high intake of the prudent pattern (OR=1.39).

Conclusions:

The SEP indicators were in different ways related to the food patterns, but the effect of occupation and income was partly explained by education, especially among women. Women's work control and men's occupation were important for their eating habits.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arkkola T, Uusitalo U, Kronberg-Kippila C, Mannisto S, Virtanen M, Kenward MG et al. (2008). Seven distinct dietary patterns identified among pregnant Finnish women—associations with nutrient intake and sociodemographic factors. Public Health Nutr 11, 176–182.

Avendano M, Kunst AE, Huisman M, Lenthe FV, Bopp M, Regidor E et al. (2006). Socioeconomic status and ischaemic heart disease mortality in 10 western European populations during the 1990s. Heart 92, 461–467.

Devine CM, Connors MM, Sobal J, Bisogni CA (2003). Sandwiching it in: spillover of work onto food choices and family roles in low- and moderate-income urban households. Soc Sci Med 56, 617–630.

Devine CM, Jastran M, Jabs J, Wethington E, Farell TJ, Bisogni CA (2006). ‘A lot of sacrifices:’work-family spillover and the food choice coping strategies of low-wage employed parents. Soc Sci Med 63, 2591–2603.

Engeset D, Alsaker E, Ciampi A, Lund E (2005). Dietary patterns and lifestyle factors in the Norwegian EPIC cohort: the Norwegian Women and Cancer (NOWAC) study. Eur J Clin Nutr 59, 675–684.

Erikson R (1992). The Constant Flux: A Study of Class Mobility in Industrial Societies. Clarendon Press: Oxford.

Fung TT, Schulze M, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB (2004). Dietary patterns, meat intake, and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Arch Intern Med 164, 2235–2240.

Fung TT, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Hu FB (2001). Dietary patterns and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. Arch Intern Med 161, 1857–1862.

Galobardes B, Lynch J, Smith GD (2007). Measuring socioeconomic position in health research. Br Med Bull 81-82, 21–37.

Giskes K, Turrell G, Van Lenthe FJ, Brug J, Mackenbach JP (2006). A multilevel study of socio-economic inequalities in food choice behaviour and dietary intake among the Dutch population: the GLOBE study. Public Health Nut 9, 75–83.

Heidemann C, Schulze MB, Franco OH, van Dam RM, Mantzoros CS, Hu FB (2008). Dietary patterns and risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all causes in a prospective cohort of women. Circulation 118, 230–237.

Hjartaker A, Lund E (1998). Relationship between dietary habits, age, lifestyle, and socio-economic status among adult Norwegian women. The Norwegian Women and Cancer Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 52, 565–572.

Hu FB, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Spiegelman D, Willett WC (2000). Prospective study of major dietary patterns and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Am J Clin Nutr 72, 912–921.

Irala-Estevez JD, Groth M, Johansson L, Oltersdorf U, Prattala R, Martinez-Gonzalez MA (2000). A systematic review of socio-economic differences in food habits in Europe: consumption of fruit and vegetables. Eur J Clin Nutr 54, 706–714.

Johansson L, Thelle DS, Solvoll K, Bjorneboe GE, Drevon CA (1999). Healthy dietary habits in relation to social determinants and lifestyle factors. Br J Nutr 81, 211–220.

Kunst AE, Groenhof F, Andersen O, Borgan JK, Costa G, Desplanques G et al. (1999). Occupational class and ischemic heart disease mortality in the United States and 11 European countries. American J Public Health 89, 47–53.

Lallukka T, Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O, Roos E, Lahelma E (2007). Multiple socio-economic circumstances and healthy food habits. Eur J Clin Nutr 61, 701–710.

Lallukka T, Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S, Roos E, Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E (2004). Working conditions and health behaviours among employed women and men: the Helsinki Health Study. Prev Med 38, 48–56.

Mackenbach JP, Bos V, Andersen O, Cardano M, Costa G, Harding S et al. (2003). Widening socioeconomic inequalities in mortality in six Western European countries. Int J Epidemiol 32, 830–837.

Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE, Cavelaars AE, Groenhof F, Geurts JJ (1997). Socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in western Europe. The EU Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health. Lancet 349, 1655–1659.

Metcalf P, Scragg R, Davis P (2006). Dietary intakes by different markers of socioeconomic status: results of a New Zealand workforce survey. N Z Med J 119, U2127.

Mishra G, Ball K, Arbuckle J, Crawford D (2002). Dietary patterns of Australian adults and their association with socioeconomic status: results from the 1995 National Nutrition Survey. Eur J Clin Nutr 56, 687–693.

Mosdøl A (2004). Dietary assessment—the weakest link?: a dissertation exploring the limitations to questionnaire based methods of dietary assessment. Doctoral Thesis, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo.

Osler M, Heitmann BL, Gerdes LU, Jorgensen LM, Schroll M (2001). Dietary patterns and mortality in Danish men and women: a prospective observational study. Br J Nutr 85, 219–225.

Perrin AE, Simon C, Hedelin G, Arveiler D, Schaffer P, Schlienger JL (2002). Ten-year trends of dietary intake in a middle-aged French population: relationship with educational level. Eur J Clin Nutr 56, 393–401.

Petkeviciene J, Klumbiene J, Prattala R, Paalanen L, Pudule I, Kasmel A (2007). Educational variations in the consumption of foods containing fat in Finland and the Baltic countries. Public Health Nutr 10, 518–523.

Raulio S, Roos E, Mukala K, Prattala R (2008). Can working conditions explain differences in eating patterns during working hours? Public Health Nutr 11, 258–270.

Robinson SM, Crozier SR, Borland SE, Hammond J, Barker DJ, Inskip HM (2004). Impact of educational attainment on the quality of young women's diets. Eur J Clin Nutr 58, 1174–1180.

Rognerud MA, Zahl PH (2006). Social inequalities in mortality: changes in the relative importance of income, education and household size over a 27-year period. Eur J Public Health 16, 62–68.

Roos E, Lahelma E, Saastamoinen P, Elstad JI (2005). The association of employment status and family status with health among women and men in four Nordic countries. Scand J Public Health 33, 250–260.

Silventoinen K, Lahelma E (2002). Health inequalities by education and age in four Nordic countries, 1986 and 1994. J Epidemiol Community Health 56, 253–258.

Slattery ML, Boucher KM, Caan BJ, Potter JD, Ma KN (1998). Eating patterns and risk of colon cancer. Am J Epidemiol 148, 4–16.

Sogaard AJ, Selmer R, Bjertness E, Thelle D (2004). The Oslo Health Study: the impact of self-selection in a large, population-based survey. Int J Equity Health 3, 3.

Stallone DD, Brunner EJ, Bingham SA, Marmot MG (1997). Dietary assessment in Whitehall II: the influence of reporting bias on apparent socioeconomic variation in nutrient intakes. Eur J Clin Nutr 51, 815–825.

Strand BH, Tverdal A (2004). Can cardiovascular risk factors and lifestyle explain the educational inequalities in mortality from ischaemic heart disease and from other heart diseases? 26 year follow up of 50 000 Norwegian men and women. J Epidemiol Community Health 58, 705–709.

The World Bank (1993). Investing in health. World Development Report. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wandel M, Fagerli RA (1999). Norwegians’ opinions of a healthy diet in different stages of life. J Nutr Educ 31, 339.

Wickrama K, Conger RD, Lorenz FO (1995). Work, marriage, lifestyle, and changes in men's physical health. J Behav Med 18, 97–111.

Wilkinson RG, Marmot MG (2006). Social Determinants of Health. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Acknowledgements

The data collection was conducted as part of the Oslo Health Study carried out in 2000–2001 as a collaboration between the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, the Oslo City Council and the University of Oslo. No external funding was used. All authors contributed in the conception and the writing of the article. Statistical analyses were executed by MKRK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Råberg Kjøllesdal, M., Holmboe-Ottesen, G. & Wandel, M. Associations between food patterns, socioeconomic position and working situation among adult, working women and men in Oslo. Eur J Clin Nutr 64, 1150–1157 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2010.116

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2010.116

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Gender-specific mediators of the association between parental education and adiposity among adolescents: the HEIA study

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Eating styles of young females in Azerbaijan

International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing (2019)

-

Perceived rules and accessibility: measurement and mediating role in the association between parental education and vegetable and soft drink intake

Nutrition Journal (2015)