Abstract

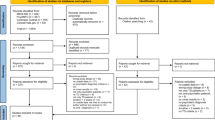

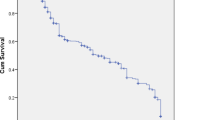

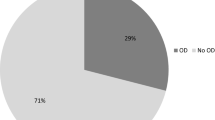

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) rates with second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are considered to be low relative to first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs), even in the particularly vulnerable elderly population. However, risk estimates are unavailable for patients naïve to FGAs. Therefore, we aimed to determine the TD incidence in particularly vulnerable, antipsychotic-naïve elderly patients treated with the SGA risperidone or olanzapine. The present work describes a prospective inception cohort study of antipsychotic-naïve elderly patients aged ⩾55 years identified at New York Metropolitan area in-patient and out-patient geriatric psychiatry facilities and nursing homes at the time of risperidone or olanzapine initiation. At baseline, 4 weeks, and at quarterly periods, patients underwent assessments of medical and medication history, abnormal involuntary movements, and extra-pyramidal signs. TD was classified using Schooler–Kane criteria. Included in the analyses were 207 subjects (age: 79.8 years, 70.0% female, 86.5% White), predominantly diagnosed with dementia (58.9%) or a major mood disorder (30.9%), although the principal treatment target was psychosis (78.7%), with (59.4%) or without (19.3%) agitation. With risperidone (n=159) the cumulative TD rate was 5.3% (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.7, 9.9%) after 1 year (mean dose: 1.0±0.76 mg/day) and 7.2% (CI: 1.4, 12.9%) after 2 years. With olanzapine (n=48) the cumulative TD rate was 6.7% (CI: 0, 15.6%) after 1 year (mean dose: 4.3±1.9 mg/day) and 11.1% (CI: 0, 23.1%) after 2 years. TD risk was higher in females, African Americans, and patients without past antidepressant treatment or with FGA co-treatment. The TD rates for geriatric patients treated with risperidone and olanzapine were comparable and substantially lower than previously reported for similar patients in direct observation studies using FGAs. This information is relevant for all patients receiving antipsychotics, not just the especially sensitive elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

American Psychiatric Association Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSMIV. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC.

Briesacher BA, Limcango MR, Simone-Wastila L, Doshi JA, Levens SR, Shea DG et al (2005). The quality of drug prescribing in nursing homes. Arch Intern Med 165: 1280–1285.

Caroff S, Mann S, Campbell ES, Sullivan KA (2002). Movement disorders associated with atypical antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry 63 (Suppl 4): 12–19.

Casey DE (1999). Tardive dyskinesia and atypical antipsychotic drugs. Schizophrenia Res 35: S61–S66.

Chakos MH, Alvir JMaJ, Woerner MG, Koreen A, Geisler S, Mayerhoff D et al (1996). Incidence and correlates of tardive dyskinesia in first episode of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53: 313–319.

Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM (2004). Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry 161: 414–425.

Correll CU, Kane JM (2007). One-year incidence rates of tardive dyskinesia in children and adolescents treated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 17: 647–656.

Correll CU, Schenk EM (2008). Tardive dyskinesia and new antipsychotics. Curr Opin Psychiatry 21: 151–156.

Davidson M, Harvey PD, Vervarcke J, Gagiano CA, De Hooge JD, Bray G, Risperidone Working Group et al (2000). A long-term, multicenter, open-label study of risperidone in elderly patients with psychosis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 15: 506–514.

de Leon J (2007). The effect of atypical vs typical antipsychotics on tardive dyskinesia: a naturalistic study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 257: 169–172.

Dolder CR, Jeste DV (2003). Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical vs atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry 53: 1142–1145.

Glazer WM, Morgenstern H, Doucette JT (1993). Predicting the long-term risk of tardive dyskinesia in outpatients maintained on neuroleptic medications. J Clin Psychiatry 54: 133–139.

Glazer WM, Morgenstern H, Doucette J (1994). Race and tardive dyskinesia among outpatients at a CMHC. Hosp Commun Psychiatry 45: 38–42.

Glazer WM, Morgenstern H, Pultz JA, Yeung PP, Rak IW (1999). Incidence of persistent tardive dyskinesia may be lower with quetiapine treatment than previously reported with typical antipsychotics in patients with psychoses. In: Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. ACNP: Nashville, TN. p 271.

Guy W (1976). ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, revised. National Institute of Mental Health: Rockville, MD. Pub. No. (ADM) 76–338. National Institute of Mental Health.

Jeste DV, Caliguiri MP, Paulsen JS, Heaton RK, Lacro JP, Harris MJ et al (1995). Risk of tardive dyskinesia in older patients: a prospective longitudinal study of 266 outpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52: 756–765.

Jeste DV, Lacro JP, Palmer B, Rockwell E, Harris MJ, Caligiuri MP (1999a). Incidence of tardive dyskinesia in early stages of low-dose treatment with typical neuroleptics in older patients. Am J Psychiatry 156: 309–311.

Jeste DV, Okamoto A, Napolitano J, Kane JM, Martinez RA (2000). Low incidence of persistent tardive dyskinesia in elderly patients with dementia treated with risperidone. Am J Psychiatry 157: 1150–1155.

Jeste DV, Rockwell E, Harris MJ, Lohr JB, Lacro J (1999b). Conventional vs newer antipsychotics in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 7: 70–76.

Kane JM, Woerner MG, Pollack S, Safferman AZ, Lieberman JA (1993). Does clozapine cause tardive dyskinesia? J Clin Psychiatry 54: 327–330.

Kinon BJ, Stauffer VL, Kaiser CJ, Hay DP, Kollack-Walker S (2005). Incidence of presumptive tardive dyskinesia in elderly patients treated with olanzapine or conventional antipsychotics. Poster Presented at the International Congress of Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. Poster no. 49.

Lee PE, Sykora K, Gill SS, Mamdani M, Marras C, Anderson G et al (2005). Antipsychotic medications and drug-induced movement disorders other than Parkinsonism: a population-based cohort study in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 53: 1374–1379.

Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, Buchanan RW, Davis JM, Kane JM et al (2002). The Mount Sinai Conference on the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 28: 5–16.

Miller DD, Caroff SN, Davis SM, Rosenheck RA, Mc E, Saltz BL et al (2008). Extrapyramidal side-effects of antipsychotics in a randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry 193: 279–288.

Morgenstern H, Glazer WM (1993). Identifying risk factors for tardive dyskinesia among neuroleptic medication: results of the Yale tardive dyskinesia study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50: 723–733.

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR (1996). A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 49: 1373–1379.

Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM (2009). Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med 360: 225–235. Erratum in N Engl J Med. 2009 Oct 29;361(18):1814.

Saltz BL, Woerner MG, Kane JM, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Bergmann KJ et al (1991). Prospective study of tardive dyskinesia incidence in the elderly. JAMA 266: 2402–2406.

SAS Institute (1989). SAS/STAT User's Guide, version 6, Vol 2, 4th edn. SAS Institute: Cary, NC.

SAS Institute (1994). SAS/STAT Software: Changes and Enhancements, SAS Institute: Cary, NC.

Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P (2005). Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 294: 1934–1943.

Schooler NR, Kane JM (1982). Research diagnoses for tardive dyskinesia (RD-TD). Arch Gen Psychiatry 39: 486–487.

Simpson GM, Angus JW (1970). A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 212: 11–19.

Simpson GM, Lee JH, Zoubok B, Gardos G (1979). A rating scale for tardive dyskinesia. Psychopharmacology 64: 171–179.

Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, Fischer MA, Mogun H, Solomon DH et al (2005). Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med 353: 2335–2341.

Woerner MG, Alvir JMaJ, Saltz BL, Lieberman JA, Kane JM (1998). Prospective study of tardive dyskinesia in the elderly: rates and risk factors. Am J Psychiatry 155: 1521–1528.

Woods SW (2003). Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 663–667.

Woods SW, Morgenstern H, Saksa JR, Walsh BC, Sullivan MC, Money R et al (2010). Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with atypical vs conventional antipsychotic medications: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry 71: 463–474.

Yassa R, Jeste DV (1997). Gender as a factor in the development of tardive dyskinesia. In: Yassa R, Nair NPV, Jeste DV (eds). Neuroleptic Induced Movement Disorder. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 40–56.

Yassa R, Nastase C, Dupont D, Thibeau M (1992). Tardive dyskinesia in elderly psychiatric patients: a 5-year study. Am J Psychiatry 149: 1206–1211.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by NIMH Grant MH 32369, an NIMH Clinical Research Center grant (MH 41960), and an NIMH Intervention Research Center grant (MH 60575) to The Zucker Hillside Hospital. We are grateful to Ann Fletcher, DiAnn Shortell-Jacobson, Donna O'Shea, MA, Erica Greenberg, MA, and Natasha Bennett, MA for participation in data collection, and Joseph Bonavisa, Ronald Brenner, MD, Edward Eschmann, Howard Guzik, MD, Lucy Macina, MD, Mary Toland, RN, and the Geriatric Psychiatry staff at The Zucker Hillside Hospital for assistance in patient recruitment. We thank Delbert Robinson, MD, for helpful comments on the work. Eli Lilly and Company and Janssen Pharmaceuticals provided medication for patients who were prescribed one of the study drugs by their treating doctor but could not afford to pay for it.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr Correll has been a consultant and/or advisor to, or has received honoraria from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, IntraCellular Therapies, Ortho-McNeill/Janssen/J&J, GSK, Hoffmann-La Roche, Medicure, Otsuka, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Supernus, Takeda, and Vanda. Dr Alvir is currently an employee of Pfizer Dr Kane has been a consultant and/or advisor to, or has received honoraria from Merck, Lundbeck, Novartis, Sepracor, Targacept, Esai, Hoffman-LaRoche, Astra-Zeneca, Janssen, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo, Johnson & Johnson, Otsuka, Vanda, Proteus, Takeda, Targacept, IntraCellular Therapies, Rules Based Medicine, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Sunovion. Drs Woerner, Greenwald, and Delman have nothing to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Woerner, M., Correll, C., Alvir, J. et al. Incidence of Tardive Dyskinesia with Risperidone or Olanzapine in the Elderly: Results from a 2-Year, Prospective Study in Antipsychotic-Naïve Patients. Neuropsychopharmacol 36, 1738–1746 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.55

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.55

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Reported time to onset of neurological adverse drug reactions among different age and gender groups using metoclopramide: an analysis of the global database Vigibase®.

European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology (2018)