Abstract

Background/objectives

Obesity prevalence in Mexican children has increased rapidly and is among the highest in the world. We aimed to estimate the longitudinal association between nonessential energy-dense food (NEDF) consumption and body mass index (BMI) in school-aged children 5 to 11 years, using a cohort study with 6 years of follow-up.

Subjects/methods

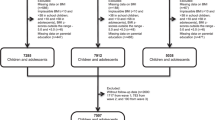

We studied the offspring of women in the Prenatal omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, child growth, and development (POSGRAD) cohort study. NEDF was classified into four main groups: chips and popcorn, sweet bakery products, non-cereal based sweets, and ready-to-eat cereals. We fitted fixed effects models to assess the association between change in NEDF consumption and changes in BMI.

Results

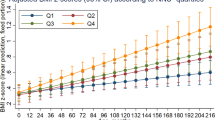

Between 5 and 11 years, children increased their consumption of NEDF by 225 kJ/day (53.9 kcal/day). In fully adjusted models, we found that change in total NEDF was not associated with change in children’s BMI (0.033 kg/m2, [p = 0.246]). However, BMI increased 0.078 kg/m2 for every 418.6 kJ/day (100 kcal/day) of sweet bakery products (p = 0.035) in fully adjusted models. For chips and popcorn, BMI increased 0.208 kg/m2 (p = 0.035), yet, the association was attenuated after adjustment (p = 0.303).

Conclusions

Changes in total NEDF consumption were not associated with changes in BMI in children. However, increases in the consumption of sweet bakery products were associated with BMI gain. NEDF are widely recognized as providing poor nutrition yet, their impact in Mexican children BMI seems to be heterogeneous.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81.

Bentham J, Di Cesare M, Bilano V, Bixby H, Zhou B, Stevens GA, et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;319:2627–42.

Hernández-Cordero S, Cuevas-Nasu L, Morales-Ruán M, Humarán IM-G, Ávila-Arcos M, Rivera-Dommarco J. Overweight and obesity in Mexican children and adolescents during the last 25 years. Nutr Diabetes. 2017;7:e247.

Shamah-Levy T, Romero-Martínez M, Barrientos-Gutiérrez T, Cuevas-Nasu L, Bautista-Arredondo S, Colchero M, et al. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2021 sobre Covid-19. Resultados nacionales. Cuernavaca, México: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; 2022.

Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Sievers ML, Bennett PH, Looker HC. Childhood obesity, other cardiovascular risk factors, and premature death. N. Eng J Med. 2010;362:485–93.

Dwyer J. Starting down the right path: nutrition connections with chronic diseases of later life. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:415S–20S.

Halldorsson TI, Gunnarsdottir I, Birgisdottir BE, Gudnason V, Aspelund T, Thorsdottir I. Childhood growth and adult hypertension in a population of high birth weight. Hypertension. 2011;58:8–15.

Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35:891–8.

Sánchez-Pimienta TG, Batis C, Lutter CK, Rivera JA. Sugar-sweetened beverages are the main sources of added sugar intake in the Mexican population. J Nutr. 2016;146:1888S–96S.

Batis C, Pedraza LS, Sánchez-Pimienta TG, Aburto TC, Rivera-Dommarco JA. Energy, added sugar, and saturated fat contributions of taxed beverages and foods in Mexico. Salud Publ Méx. 2017;59:512–7.

Romieu I, Dossus L, Barquera S, Blottière HM, Franks PW, Gunter M, et al. Energy balance and obesity: what are the main drivers? Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28:247–58.

Cornwell B, Villamor E, Mora-Plazas M, Marin C, Monteiro CA, Baylin A. Processed and ultra-processed foods are associated with lower-quality nutrient profiles in children from Colombia. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:142–7.

Larson NI, Miller JM, Watts AW, Story MT, Neumark-Sztainer DR. Adolescent snacking behaviors are associated with dietary intake and weight status. J Nutr. 2016;146:1348–55.

Aburto TC, Pedraza LS, Sánchez-Pimienta TG, Batis C, Rivera JA. Discretionary foods have a high contribution and fruit, vegetables, and legumes have a low contribution to the total energy intake of the Mexican population. J Nutr. 2016;146:1881S–7S.

Bonvecchio-Arenas A, Theodore FL, Hernández-Cordero S, Campirano-Núñez F, Islas AL, Safdie M, et al. The school as an opportunity for obesity prevention: an experience from the Mexican school system. Rev Espanola de Nutr Comunitaria. 2010;16:13–6.

Ramírez-Ley K, De Lira-García C, de las Cruces Souto-Gallardo M, Tejeda-López MF, Castañeda-González LM, Bacardí-Gascón M, et al. Food-related advertising geared toward Mexican children. J Public Health. 2009;31:383–8.

Calvert SL. Children as consumers: advertising and marketing. Future Child. 2008;18:205–34.

Prentice AM, Jebb SA. Fast foods, energy density and obesity: a possible mechanistic link. Obes Rev. 2003;4:187–94.

Neri D, Steele EM, Khandpur N, Cediel G, Zapata ME, Rauber F, et al. Ultraprocessed food consumption and dietary nutrient profiles associated with obesity: a multicountry study of children and adolescents. Obes Rev. 2022;23:e13387.

Dicken SJ, Batterham RL. Ultra-processed food and obesity: what is the evidence? Curr Nutr Rep. 2024;13:23–38.

Popkin BM, Barquera S, Corvalan C, Hofman KJ, Monteiro C, Ng SW, et al. Towards unified and impactful policies to reduce ultra-processed food consumption and promote healthier eating. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:462–70.

Cunha DB, Costa THM, Veiga GV, Pereira RA, Sichieri R. Ultra-processed food consumption and adiposity trajectories in a Brazilian cohort of adolescents: ELANA study. Nutr Diabetes. 2018;8:28.

Durão C, Severo M, Oliveira A, Moreira P, Guerra A, Barros H, et al. Evaluating the effect of energy-dense foods consumption on preschool children’s body mass index: a prospective analysis from 2 to 4 years of age. Eur J Nutr. 2015;54:835–43.

Shroff MR, Perng W, Baylin A, Mora-Plazas M, Marin C, Villamor E. Adherence to a snacking dietary pattern and soda intake are related to the development of adiposity: a prospective study in school-age children. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1507–13.

Phillips SM, Bandini LG, Naumova EN, Cyr H, Colclough S, Dietz WH, et al. Energy‐dense snack food intake in adolescence: longitudinal relationship to weight and fatness. Obes Res. 2004;12:461–72.

Field AE, Austin SB, Gillman MW, Rosner B, Rockett HR, Colditz GA. Snack food intake does not predict weight change among children and adolescents. Int J Obes. 2004;28:1210–16.

Gonzalez-Casanova I, Stein AD, Hao W, Garcia-Feregrino R, Barraza-Villarreal A, Romieu I, et al. Prenatal supplementation with docosahexaenoic acid has no effect on growth through 60 months of age–3. J Nutr. 2015;145:1330–4.

Lohman T, Roche A, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual Abridged Edition: Human Kinetics Books; 1991. Available from: http://books.google.com.mx/books?id=wgd9QgAACAAJ.

World Health Organization. WHO AnthroPlus for personal computers manual: software for assessing growth of the world’s children and adolescents. (Geneva: WHO. 2009). Available from: https://www.who.int/growthref/tools/en/.

De Onis M WHO child growth standards: Methods and development - Length/Height-for-age, Weight-for-age, Weight-for-length, Weight-for-height and Body mass index-for-age 2006. Available from: https://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/Technical_report.pdf?ua=1.

Angulo-Estrada JS, Espinosa-Montero J, Gaytan-Colin MA, González-de-Cossío-Martínez T, Gutiérrez JP, Barrera LH, et al. Programa de Cómputo: Rec24Hrs. 5 Pasos (R24H5). Cuernavaca, Morelos: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; 2013.

Conway JM, Ingwersen LA, Vinyard BT, Moshfegh AJ. Effectiveness of the US Department of Agriculture 5-step multiple-pass method in assessing food intake in obese and nonobese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1171–8.

Ramírez Silva I, Barragán-Vázquez S, Rodríguez-Ramírez S, Rivera-Dommarco J, Mejía-Rodríguez F, Barquera-Cervera S, et al. Base de alimentos de México (BAM): Compilación de la composición de los alimentos frecuentemente consumidos en el país. 2019. Available from: https://insp.mx/informacion-relevante/bam-bienvenida.

Congreso de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Ley del Impuesto Especial sobre Producción y Servicios Mexico2014. Available from: http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/78_241219.pdf.

Bitok E, Sabate J. Nuts and cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;61:33–7.

Kris-Etherton PM, Hu FB, Ros E, Sabaté J. The role of tree nuts and peanuts in the prevention of coronary heart disease: multiple potential mechanisms. J Nutr. 2008;138:1746S–51S.

Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N. Eng J Med. 2011;364:2392–404.

Hernández B, Gortmaker SL, Laird NM, Colditz GA, Parra-Cabrera S, Peterson KE. Validez y reproducibilidad de un cuestionario de actividad e inactividad física para escolares de la ciudad de México. Salud Publica Mex. 2000;42:315–23.

Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: modeling change and event occurrence: Oxford University Press; 2003. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/book/41753.

Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm E, Ascherio A, Rosner BA, Spiegelman D, et al. Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: a comparison of approaches for adjusting for total energy intake and modeling repeated dietary measurements. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:531–40.

StataCorp L. Stata 13: College Station: StataCorp LP; 2014. Available from: https://www.stata.com/company/.

Juul F, Martinez-Steele E, Parekh N, Monteiro CA, Chang VW. Ultra-processed food consumption and excess weight among US adults. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:90–100.

Priebe MG, McMonagle JR. Effects of ready-to-eat-cereals on key nutritional and health outcomes: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164931.

Michels N, De Henauw S, Beghin L, Cuenca-García M, Gonzalez-Gross M, Hallstrom L, et al. Ready-to-eat cereals improve nutrient, milk and fruit intake at breakfast in European adolescents. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:771–9.

Frantzen LB, Treviño RP, Echon RM, Garcia-Dominic O, DiMarco N. Association between frequency of ready-to-eat cereal consumption, nutrient intakes, and body mass index in fourth-to sixth-grade low-income minority children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:511–9.

Kuriyan R, Lokesh DP, D’souza N, Priscilla DJ, Peris CH, Selvam S, et al. Portion controlled ready-to-eat meal replacement is associated with short term weight loss: a randomised controlled trial. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26:1055–65.

Donin AS, Nightingale CM, Owen CG, Rudnicka AR, Perkin MR, Jebb SA, et al. Regular breakfast consumption and type 2 diabetes risk markers in 9-to 10-year-old children in the child heart and health study in England (CHASE): a cross-sectional analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001703.

Hall KD. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: a one-month inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019;30:67–77.e3.

Bornet FR, Jardy-Gennetier A-E, Jacquet N, Stowell J. Glycaemic response to foods: impact on satiety and long-term weight regulation. Appetite. 2007;49:535–53.

Hall KD. A review of the carbohydrate–insulin model of obesity. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71:323–6.

Simpson S, Raubenheimer D. Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis. Obes Rev. 2005;6:133–42.

World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Buse K, Hawkes S. Health in the sustainable development goals: ready for a paradigm shift? Glob Health. 2015;11:13.

Secretaría de Salud. Acuerdo Nacional para la Salud Alimentaria. Estrategia contra el sobrepeso y la obesidad. México: Secretaría de Salud; 2010. Available from: https://www.sep.gob.mx/work/models/sep1/Resource/635/1/images/programadeaccion_sept.pdf.

Consejo de autoregulación y ética publicitariar. Código PABI. Código de autoregulación de publicidad de alimentos y bebidas no alcohólicas dirigida al público infantil. Ciudad de México: CONAR; 2012. Available from: https://www.conar.org.mx/pdf/codigo_pabi.pdf.

Funding

Primary funding for the study came from the National Institute of Public Health and from National Institutes of Health Grant Number R01DK108148.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DI-Z conceived the design research, performed the computations and was the major contributor in writing the manuscript. CB, GMS, DM and TB-G, assisted in the statistical analysis and contributed to writing the manuscript. AB-V, IR-S and IR contributed to the follow-up of the cohort and supervised the cleaning and processing data. IR-S derived the nonessential energy-dense food database. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol was approved by the Ethics, Biosafety, and Research Committees’ of the National Institute of Public Health of Mexico and the Emory University. Parental signed consent and children’s informed consent were obtained at each wave of the study. This investigation conformed to all principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Illescas-Zárate, D., Batis, C., Singh, G.M. et al. Association between consumption of nonessential energy-dense food and body mass index among Mexican school-aged children: a prospective cohort study. Int J Obes 48, 1292–1299 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01552-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01552-0