Abstract

Objective

Diazoxide is used to treat infants with persistent hypoglycemia, but the prevalence of its use and adverse effects are not well described. We report demographic and clinical characteristics of infants treated with diazoxide in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs).

Study design

Retrospective cohort study of infants 24–41 weeks’ gestation admitted to 392 NICUs from 1997–2016, comparing characteristics between hypoglycemic infants exposed/not exposed to diazoxide. For diazoxide courses > 1 day, we report percentages of infants starting diuretics and/or developing new ventilator/oxygen requirement during therapy.

Results

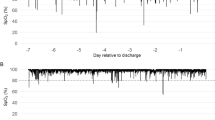

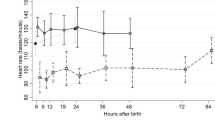

Among 1,249,466 infants, 185,832 had hypoglycemia; 1066/185,832 (0.57%) received diazoxide. Diazoxide use increased over time (P = 0.001). Infants receiving diazoxide varied from 0–14.9% among centers. New diuretic courses were associated with 91/664 (14%), and new oxygen or ventilator requirement during therapy was associated with 64/556 (12%) and 34/647 (5%), respectively.

Conclusions

Diazoxide use in NICU settings has increased over time. Infants receiving diazoxide commonly received diuretics.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Güemes M, Hussain K. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62:1017–36.

Thornton PS, Stanley CA, De Leon DD, Harris D, Haymond MW, Hussain K, et al. Recommendations from the Pediatric Endocrine Society for Evaluation and Management of Persistent Hypoglycemia in Neonates, Infants, and Children. J Pediatr. 2015;167:238–45.

Adamkin DH. Committee on fetus and newborn. Postnatal glucose homeostasis in late-preterm and term infants. Pediatrics. 2011;127:575–9.

Sweet CB, Grayson S, Polak M. Management strategies for neonatal hypoglycemia. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2013;18:199–208.

Stanley CA, Rozance PJ, Thornton PS, De Leon DD, Harris D, Haymond MW, et al. Re-evaluating “transitional neonatal hypoglycemia”: mechanism and implications for management. J Pediatr. 2015;166:1520–5.e1.

Harris DL, Weston PJ, Harding JE. Incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in babies identified as at risk. J Pediatr. 2012;161:787–91.

Hoe FM, Thornton PS, Wanner LA, Steinkrauss L, Simmons RA, Stanley CA. Clinical features and insulin regulation in infants with a syndrome of prolonged neonatal hyperinsulinism. J Pediatr. 2006;148:207–12.

National Library of Medicine. DaileyMed. Package insert: Proglycem-diazoxide suspension. 2 October, 2015. Available at: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=b16c7832-2fd9-49af-b923-1dc0d91fd6e2. Accessed 4 Dec, 2017.

Rozenkova K, Guemes M, Shah P, Hussain K. The diagnosis and management of hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2015;7:86–97.

Welters A, Lerch C, Kummer S, Marquard J, Salgin B, Mayatepek E, et al. Long- term medical treatment in congenital hyperinsulinism: a descriptive analysis in a large cohort of patients from different clinical centers. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:150.

Hu S, Xu Z, Yan J, Liu M, Sun B, Li W, et al. The treatment effect of diazoxide on 44 patients with congenital hyperinsulinism. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25:1119–22.

Abu-Osba YK, Manasra KB, Mathew PM. Complications of diazoxide treatment in persistent neonatal hyperinsulinism. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64:1496–1500.

Nebesio TD, Hoover WC, Caldwell RL, Nitu ME, Eugster EA. Development of pulmonary hypertension in an infant treated with diazoxide. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007;20:939–44.

Demirel F, Unal S, Cetin II, Esen I, Arasli A. Pulmonary hypertension and reopening of the ductus arteriosus in an infant treated with diazoxide. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2011;24:603–5.

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Podcast: FDA warns about a serious lung condition in infants and newborns treated with Proglycem (diazoxide). 16 July, 2015. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugSafetyPodcasts/ucm455659.htm

Rozance PJ. Update on neonatal hypoglycemia. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2014;21:45–50.

Gillies DR. Complications of diazoxide in the treatment of nesidioblastosis. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:500–1.

Spitzer AR, Ellsbury DL, Handler D, Clark RH. The pediatrix babysteps data warehouse and the pediatrix qualitysteps improvement project system--tools for “meaningful use” in continuous quality improvement. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:49–70.

Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, Clark RH, Zemel BS. New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e214–24.

Hornik CP, Fort P, Clark RH, Watt K, Benjamin DK Jr., Smith PB, et al. Early and late onset sepsis in very-low-birth-weight infants from a large group of neonatal intensive care units. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88(Suppl 2):S69–74.

Cuzick J. A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med. 1985;4:87–90.

Flanagan SE, Kapoor RR, Mali G, Cody D, Murphy N, Schwahn B, et al. Diazoxide- responsive hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia caused by HNF4A gene mutations. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:987–92.

Rozance PJ, Hay WW Jr. New approaches to management of neonatal hypoglycemia. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2016;2:3.

Erjavec K, Poljicanin T, Matijevic R. Impact of the implementation of new WHO diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus on prevalence and perinatal outcomes: A population-based study. J Pregnancy. 2016;2016:2670912.

World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data 2016–Overweight and obesity. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/overweight/en/. Accessed 4 Dec, 2017.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ. Births in the United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;287:1–8.

Collins JE, Leonard JV, Teale D, Marks V, Williams DM, Kennedy CR, et al. Hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia in small for dates babies. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:1118–20.

Yamamoto JM, Kallas-Koeman MM, Butalia S, Lodha AK, Donovan LE Large-for- gestational-age (LGA) neonate predicts a 2.5-fold increased odds of neonatal hypoglycaemia in women with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2017;33:e2824.

Bartorelli C, Gargano N, Leonetti G, Zanchetti A. Hypotensive and renal effects of diazoxide, a sodiumretaining benzothiadiazine compound. Circulation. 1963;27:895–903.

Hutcheon DE, Barthalmus KS. Antihypertensive action of diazoxide. A new benzothiazine with antidiuretic properties. Br Med J. 1962;2:159–61.

Green TP. Systemic vasodilatation and renal sodium excretion: effects of hydralazine and diazoxide. Life Sci. 1984;34:2169–76.

Tas E, Mahmood B, Garibaldi L, Sperling M. Liver injury may increase the risk of diazoxide toxicity: a case report. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174:403–6.

Yoshida K, Kawai M, Marumo C, Kanazawa H, Matsukura T, Kusuda S, et al. High prevalence of severe circulatory complications with diazoxide in premature infants. Neonatology. 2014;105:166–71.

Silvani P, Camporesi A, Mandelli A, Wolfler A, Salvo I. A case of severe diazoxide toxicity. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14:607–9.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was funded under National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) contract HHSN275201000003I (principal investigator: Benjamin) for the Pediatric Trials Network.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. DK Benjamin receives support from the National Institutes of Health (award 2K24HD058735-06, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HHSN275201000003I), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (HHSN272201500006I), ECHO Program (1U2COD023375-01), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (1U24TR001608-01); he also receives research support from Cempra Pharmaceuticals (subaward to HHSO100201300009C) and consulting payments from AstraZeneca, Cempra, Shionogi Inc., The Medicines Company, Allergan, Astellas Pharma, Cidara Therapeutics, Purdue Pharma, and UCB Biosciences, Inc. Dr. R Benjamin serves on the Speaker’s Bureau for Pfizer. Dr. Clark is an employee of Pediatrix Medical Group, Inc. Dr. Cotten receives grant funding from the NIH (5U10 HD040492-16 and 1R01-EY025009-01A1). Dr. Greenberg receives salary support for research from NIH awards (HHSN 275201000003I, HHSN 272201300017I, HHSN200201253663), and from the Food and Drug Administration (HHSF223201610082C). The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gray, K.D., Dudash, K., Escobar, C. et al. Prevalence and safety of diazoxide in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol 38, 1496–1502 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-018-0218-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-018-0218-4

This article is cited by

-

Higher C-peptide levels and glucose requirements may identify neonates with transient hyperinsulinism hypoglycemia who will benefit from diazoxide treatment

European Journal of Pediatrics (2020)

-

Genotype and phenotype analysis of a cohort of patients with congenital hyperinsulinism based on DOPA-PET CT scanning

European Journal of Pediatrics (2019)

-

Current and Emerging Agents for the Treatment of Hypoglycemia in Patients with Congenital Hyperinsulinism

Pediatric Drugs (2019)