Abstract

Objective

Not all individuals self-identify with race categories on birth certificates, selecting “Other” and writing in identities. Our hypothesis was that curating write-in responses in the “Other” race category would contribute to understanding preterm birth inequities.

Methods

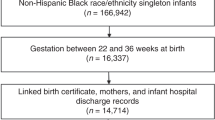

We analyzed Pennsylvania birth certificates (2006–2014). Two independent coders reviewed each write-in response among those who selected “Other” race. We compared preterm birth rates across subpopulations within “Other” race category using a Monte Carlo simulated Chi-square test.

Results

Among 1,196,125 singleton births, 72,891 (6.1%) exclusively selected “Other” race; Hispanic more often than non-Hispanic individuals (54.5% vs 0.7%), p < 0.0001). Only 545 (0.8%) of Hispanic individuals wrote in responses aligned with preestablished race categories compared to 2,601 (33.2%) of non-Hispanic individuals. Preterm birth rates varied significantly across identities within the “Other” group (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Utilizing combinations of self-identified race, ethnicity, and continental origin may facilitate public health efforts focused on birth outcome equity.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data is available from the Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council (PHC4, https://www.phc4.org/browse-our-data/).

References

Driscoll AK, Ely DM. Disparities in infant mortality by maternal race and Hispanic origin, 2017-2018. Semin Perinatol. 2022;46:151656.

Ely DM, Driscoll AK. Infant Mortality in the United States, 2021: Data From the Period Linked Birth/Infant Death File. Natl Vital Stat Rep Cent Dis Control Prev Natl Cent Health Stat Natl Vital Stat Syst. 2023;72:1–19.

Hahn RA, Mulinare J, Teutsch SM. Inconsistencies in coding of race and ethnicity between birth and death in US infants. A new look at infant mortality, 1983 through 1985. JAMA. 1992;267:259–63.

Brumberg HL, Dozor D, Golombek SG. History of the birth certificate: from inception to the future of electronic data. J Perinatol. 2012;32:407–11.

Weikel BW, Klawetter S, Bourque SL, Hannan KE, Roybal K, Soondarotok M, et al. Defining an Infant’s Race and Ethnicity: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2023;151:e2022058756.

US Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS). 2023. Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 13 Dec 2023.

P1: RACE - Census Bureau Table. 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALPL2020.P1;https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALPL2010.P1. Both accessed 14 Feb 2024.

NHIS-Detailed Race and Ethnicity Summary Health Statistics. 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/NHISDataQueryTool/SHS_adult3yr/index.html. Accessed 13 Dec 2023.

Holloway K, Radack J, Passarella M, Ellison AM, Chaiyachati BH, Burris HH, et al. Avoiding loss of native individuals in birth certificate data. J Perinatol J Calif Perinat Assoc. 2023;43:385–6.

The United Nations and Decolonization - Committee of 24 - Non-Self-Governing Territories. 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140227010648/http://www.un.org/en/decolonization/nonselfgovterritories.shtml. Accessed 27 Feb 2024.

Race - Health, United States. 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/sources-definitions/race.htm. Accessed 19 Jul 2024.

List of Countries by Continent. 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/list-of-countries-by-continent. Accessed 21 Feb 2024.

Martin JA, Osterman MJK, Kirmeyer SE, Gregory ECW. Measuring Gestational Age in Vital Statistics Data: Transitioning to the Obstetric Estimate. Natl Vital Stat Rep Cent Dis Control Prev Natl Cent Health Stat Natl Vital Stat Syst. 2015;64:1–20.

Bradley DR, Cutcomb S. Monte Carlo simulations and the chi-square test of independence. Behav Res Methods Instrum. 1977;9:193–201.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–9.

Vang ZM, Elo IT, Nagano M. Preterm birth among the Hmong, other Asian subgroups and non-Hispanic whites in California. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:184.

DeSisto CL, McDonald JA. Variation in Birth Outcomes by Mother’s Country of Birth Among Hispanic Women in the United States, 2013. Public Health Rep. 2018;133:318–28.

Dongarwar D, Tahseen D, Wang L, Aliyu MH, Salihu HM. Trends and predictors of preterm birth among Asian Americans by ethnicity, 1992-2018. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet. 2022;35:5881–7.

Mittermaier M, Raza MM, Kvedar JC. Bias in AI-based models for medical applications: challenges and mitigation strategies. Npj Digit Med. 2023;6:1–3.

Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Fed. Regist. 2024. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/03/29/2024-06469/revisions-to-ombs-statistical-policy-directive-no-15-standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and. Accessed 17 Jun 2024.

Initial Proposals For Updating OMB’s Race and Ethnicity Statistical Standards. Fed Regist. 2023. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/01/27/2023-01635/initial-proposals-for-updating-ombs-race-and-ethnicity-statistical-standards. Accessed 18 Dec 2023.

Maghbouleh N, Schachter A, Flores RD. Middle Eastern and North African Americans may not be perceived, nor perceive themselves, to be White. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119:e2117940119.

Editors of Community Biology. #Black Lives Matter. Commun Biol. 2020;3:332.

Zhou S, Banawa R, Oh H. Stop Asian hate: The mental health impact of racial discrimination among Asian Pacific Islander young and emerging adults during COVID-19. J Affect Disord. 2023;325:346–53.

Fernander A. What does critical race theory have to do with academic medicine? J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;114:274–7.

Hannah-Jones N. The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story. New York, NY: Random House Publishing Group; 2021.

The 1619 Project. N. Y. Times. 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html. Accessed 13 Dec 2023.

Institute of Medicine Board on Health Care Service Subcommittee on Standardized Collection of Race/Ethnicity Data for Healthcare Quality Improvement. Race, Ethnicity, and Language Data: Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

Bureau UC. Over Half a Million People Self-Identified as Brazilian in 2020 Census. 2023. Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/10/2020-census-dhc-a-some-other-race-population.html. Accessed 17 Jun 2024.

Cheng ER, Hawkins SS, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW, Taveras EM. Association of missing paternal demographics on infant birth certificates with perinatal risk factors for childhood obesity. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:453.

Funding

The time of BHC is supported by career development award NIH K08MH129657 and the time of DM-W is supported by career development award NIH K23HD102526.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KRH and HHB conceived of the study. KBH and AB reviewed each race written-in response. JR performed the analysis. BHC, DMH, AME participated in each study meeting, providing scientific guidance. KRH drafted the manuscript with mentorship from HHB. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest and have no relevant financial disclosures. The Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council (PHC4) is an independent state agency responsible for addressing the problem of escalating health costs, ensuring the quality of health care, and increasing access to health care for all citizens regardless of ability to pay. PHC4 has provided data to this entity in an effort to further PHC4’s mission of educating the public and containing health care costs in Pennsylvania. PHC4, its agents, and staff, have made no representation, guarantee, or warranty, express or implied, that the data – financial, patient, payor, and physician specific information – provided to this entity, are errorfree, or that the use of the data will avoid differences of opinion or interpretation. This analysis was not prepared by PHC4. This analysis was done by investigators at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. PHC4, its agents and staff, bear no responsibility or liability for the results of the analysis, which are solely the opinion of this entity.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Holloway, K.R., Radack, J., Barreto, A. et al. The “Other” race category on birth certificates and its impact on analyses of preterm birth inequity. J Perinatol 45, 372–377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-02123-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-02123-x