Abstract

Background

This study examined the relationship between prenatal maternal stress (PREMS) and non-nutritive suck (NNS) and tested its robustness across 2 demographically diverse populations.

Methods

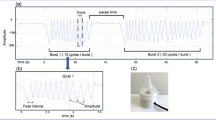

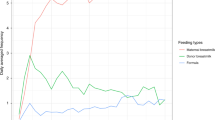

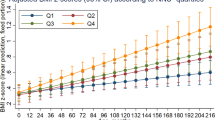

The study involved 2 prospective birth cohorts participating in the national Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Program: Illinois Kids Development Study (IKIDS) and ECHO Puerto Rico (ECHO-PROTECT). PREMS was measured during late pregnancy via the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10). NNS was sampled from 1- to 8-week-olds using a custom pacifier for ~5 min.

Results

Overall, 237 mother–infant dyads completed this study. Despite several significant differences, including race/ethnicity, income, education, and PREMS levels, significant PREMS-NNS associations were found in the 2 cohorts. In adjusted linear regression models, higher PREMS, measured through PSS-10 total scores, related to fewer but longer NNS bursts per minute.

Conclusions

A significant association was observed between PREMS and NNS across two diverse cohorts. This finding is important as it may enable the earlier detection of exposure-related deficits and, as a result, earlier intervention, which potentially can optimize outcomes. More research is needed to understand how NNS affects children’s neurofunction and development.

Impact

-

In this double-cohort study, we found that higher maternal perceived stress assessed in late pregnancy was significantly associated with fewer but longer sucking bursts in 1- to 8-week-old infants.

-

This is the first study investigating the association between prenatal maternal stress (PREMS) and infant non-nutritive suck (NNS), an early indicator of central nervous system integrity.

-

Non-nutritive suck is a potential marker of increased prenatal stress in diverse populations.

-

Non-nutritive suck can potentially serve as an early indicator of exposure-related neuropsychological deficits allowing for earlier interventions and thus better prognoses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Woody, C. A., Ferrari, A. J., Siskind, D. J., Whiteford, H. A. & Harris, M. G. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J. Affect Disord. 219, 86–92 (2017).

Dennis, C. L., Falah-Hassani, K. & Shiri, R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 210, 315–323 (2017).

Loomans, E. M. et al. Psychosocial stress during pregnancy is related to adverse birth outcomes: results from a large multi-ethnic community-based birth cohort. Eur. J. Public Health 23, 485–491 (2013).

Phelan, A. L., DiBenedetto, M. R., Paul, I. M., Zhu, J. & Kjerulff, K. H. Psychosocial stress during first pregnancy predicts infant health outcomes in the first postnatal year. Matern. Child Health J. 19, 2587–2597 (2015).

Yuksel, F., Akin, S. & Durna, Z. Prenatal distress in Turkish pregnant women and factors associated with maternal prenatal distress. J. Clin. Nurs. 23, 54–64 (2014).

Hou, Q. et al. The associations between maternal lifestyles and antenatal stress and anxiety in Chinese pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 8, 10771 (2018).

Tang, X., Lu, Z., Hu, D. & Zhong, X. Influencing factors for prenatal stress, anxiety and depression in early pregnancy among women in Chongqing, China. J. Affect Disord. 253, 292–302 (2019).

Woods, S. M., Melville, J. L., Guo, Y., Fan, M. Y. & Gavin, A. Psychosocial stress during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 202, 61 e61–61.e67 (2010).

Dunkel Schetter, C. & Tanner, L. Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 25, 141–148 (2012).

Fenster, L. et al. Psychologic stress in the workplace and spontaneous abortion. Am. J. Epidemiol. 142, 1176–1183 (1995).

Hansen, D., Lou, H. C. & Olsen, J. Serious life events and congenital malformations: a national study with complete follow-up. Lancet 356, 875–880 (2000).

Lou, H. C. et al. Prenatal stressors of human life affect fetal brain development. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 36, 826–832 (1994).

Neugebauer, R. et al. Association of stressful life events with chromosomally normal spontaneous abortion. Am. J. Epidemiol. 143, 588–596 (1996).

Nimby, G. T., Lundberg, L., Sveger, T. & McNeil, T. F. Maternal distress and congenital malformations: do mothers of malformed fetuses have more problems? J. Psychiatr. Res. 33, 291–301 (1999).

Paarlberg, K. M. et al. Psychosocial factors and pregnancy outcome: a review with emphasis on methodological issues. J. Psychosom. Res. 39, 563–595 (1995).

Glover, V. Annual Research Review: Prenatal stress and the origins of psychopathology: an evolutionary perspective. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 52, 356–367 (2011).

Talge, N. M., Neal, C. & Glover, V. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48, 245–261 (2007).

Van den Bergh, B. R., Mulder, E. J., Mennes, M. & Glover, V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 29, 237–258 (2005).

Buss, C., Davis, E. P., Muftuler, L. T., Head, K. & Sandman, C. A. High pregnancy anxiety during mid-gestation is associated with decreased gray matter density in 6-9-year-old children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 141–153 (2010).

Glover, V., O’Connor, T. G., Heron, J., Golding, J. & team, A. S. Antenatal maternal anxiety is linked with atypical handedness in the child. Early Hum. Dev. 79, 107–118 (2004).

Obel, C., Hedegaard, M., Henriksen, T. B., Secher, N. J. & Olsen, J. Psychological factors in pregnancy and mixed-handedness in the offspring. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 45, 557–561 (2003).

King, S. et al. Prenatal maternal stress from a natural disaster predicts dermatoglyphic asymmetry in humans. Dev. Psychopathol. 21, 343–353 (2009).

Kleinhaus, K. et al. Prenatal stress and affective disorders in a population birth cohort. Bipolar Disord. 15, 92–99 (2013).

O’Connor, T. G., Heron, J., Golding, J., Glover, V. & Team, A. S. Maternal antenatal anxiety and behavioural/emotional problems in children: a test of a programming hypothesis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 44, 1025–1036 (2003).

Rice, F. et al. The links between prenatal stress and offspring development and psychopathology: disentangling environmental and inherited influences. Psychol. Med. 40, 335–345 (2010).

Rodriguez, A. & Bohlin, G. Are maternal smoking and stress during pregnancy related to ADHD symptoms in children? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 46, 246–254 (2005).

Laplante, D. P., Brunet, A., Schmitz, N., Ciampi, A. & King, S. Project Ice Storm: prenatal maternal stress affects cognitive and linguistic functioning in 5 1/2-year-old children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 47, 1063–1072 (2008).

Mennes, M., Stiers, P., Lagae, L. & Van den Bergh, B. Long-term cognitive sequelae of antenatal maternal anxiety: involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 30, 1078–1086 (2006).

Anderson, P. J. et al. Underestimation of developmental delay by the new Bayley-III Scale. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 164, 352–356 (2010).

Anderson, P. J. & Burnett, A. Assessing developmental delay in early childhood—concerns with the Bayley-III scales. Clin. Neuropsychol. 31, 371–381 (2017).

Spencer-Smith, M. M., Spittle, A. J., Lee, K. J., Doyle, L. W. & Anderson, P. J. Bayley-III cognitive and language scales in preterm children. Pediatrics 135, e1258–e1265 (2015).

Slattery, J., Morgan, A. & Douglas, J. Early sucking and swallowing problems as predictors of neurodevelopmental outcome in children with neonatal brain injury: a systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 54, 796–806 (2012).

Wolff, P. H. The serial organization of sucking in the young infant. Pediatrics 42, 943–956 (1968).

Barlow, S. M., Burch, M., Venkatesan, L., Harold, M. & Zimmerman, E. Frequency modulation and spatiotemporal stability of the sCPG in preterm infants with RDS. Int. J. Pediatr. 2012, 581538 (2012).

Zimmerman, E. & DeSousa, C. Social visual stimuli increase infants suck response: a preliminary study. PLoS ONE 13, e0207230 (2018).

Estep, M., Barlow, S. M., Vantipalli, R., Finan, D. & Lee, J. Non-nutritive suck parameter in preterm infants with RDS. J. Neonatal Nurs. 14, 28–34 (2008).

Wolthuis-Stigter, M. I. et al. Sucking behaviour in infants born preterm and developmental outcomes at primary school age. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 59, 871–877 (2017).

Wolthuis-Stigter, M. I. et al. The association between sucking behavior in preterm infants and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years of age. J. Pediatr. 166, 26–30 (2015).

LeWinn, K. Z., Caretta, E., Davis, A., Anderson, A. L., Oken E. & Program Collaborators for Environmental Influences on Child Health O. SPR perspectives: environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Program: overcoming challenges to generate engaged, multidisciplinary science. Pediatr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01598-0 (2021).

Eick, S. M. et al. Associations of maternal stress, prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and demographic risk factors with birth outcomes and offspring neurodevelopment: an overview of the ECHO.CA.IL Prospective Birth Cohorts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 742 (2021).

Ferguson, K. K. et al. Demographic risk factors for adverse birth outcomes in Puerto Rico in the PROTECT cohort. PLoS ONE 14, e0217770 (2019).

Manjourides, J. et al. Cohort profile: center for research on early childhood exposure and development in Puerto Rico. BMJ Open 10, e036389 (2020).

Cohen, S. Perceived Stress Scale. https://www.mindgarden.com/documents/PerceivedStressScale.pdf (1994).

Cohen, S. & Janicki-Deverts, D. Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. J. Appl Soc. Psychol. 42, 1320–1334 (2012).

Lee, E. H. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale (vol 6, pg 121, 2012). Asian Nurs. Res. 7, 160–160 (2013).

MD APP. Perceived Stress Scale Calculator. https://www.mdapp.co/perceived-stress-scale-pss-calculator-389/ (2020).

Zimmerman, E. et al. Associations of gestational phthalate exposure and non-nutritive suck among infants from the Puerto Rico Testsite for Exploring Contamination Threats (PROTECT) birth cohort study. Environ. Int. 152, 106480 (2021).

Martens, A., Hines, M. & Zimmerman, E. Changes in non-nutritive suck between 3 and 12 months. Early Hum. Dev. 149, 105141 (2020).

Willer, C. J., Li, Y. & Abecasis, G. R. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 26, 2190–2191 (2010).

Hernan, M. A., Hernandez-Diaz, S., Werler, M. M. & Mitchell, A. A. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. Am. J. Epidemiol. 155, 176–184 (2002).

Shrier, I. & Platt, R. W. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8, 70 (2008).

Williams, T. C., Bach, C. C., Matthiesen, N. B., Henriksen, T. B. & Gagliardi, L. Directed acyclic graphs: a tool for causal studies in paediatrics. Pediatr. Res. 84, 487–493 (2018).

Lin, S. & Kelsey, J. Use of race and ethnicity in epidemiologic research: concepts, methodological issues, and suggestions for research. Epidemiol. Rev. 22, 187–202 (2000).

Oh, S. S. et al. Diversity in clinical and biomedical research: a promise yet to be fulfilled. PLoS Med. 12, e1001918 (2015).

Motel, S. & Patten, E. Hispanics of Puerto Rican Origin in the Unites States, 2010 (2012).

Cantonwine, D. E. et al. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations among pregnant women in Northern Puerto Rico: distribution, temporal variability, and predictors. Environ. Int. 62, 1–11 (2014).

Ferguson, K. K. et al. Environmental phthalate exposure and preterm birth in the PROTECT birth cohort. Environ. Int. 132, 105099 (2019).

Field, T. et al. Nonnutritive sucking during tube feedings: effects on preterm neonates in an intensive care unit. Pediatrics 70, 381–384 (1982).

Boyle, E. M. et al. Sucrose and non-nutritive sucking for the relief of pain in screening for retinopathy of prematurity: a randomised controlled trial. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 91, F166–F168 (2006).

Foster, J. P., Psaila, K. & Patterson, T. Non-nutritive sucking for increasing physiologic stability and nutrition in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, CD001071 (2016).

DiPietro, J. A., Hodgson, D. M., Costigan, K. A. & Johnson, T. R. Fetal antecedents of infant temperament. Child Dev. 67, 2568–2583 (1996).

DiPietro, J. A., Costigan, K. A. & Gurewitsch, E. D. Fetal response to induced maternal stress. Early Hum. Dev. 74, 125–138 (2003).

Kinsella, M. T. & Monk, C. Impact of maternal stress, depression and anxiety on fetal neurobehavioral development. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 52, 425–440 (2009).

DiPietro, J. A., Costigan, K. A., Shupe, A. K., Pressman, E. K. & Johnson, T. R. Fetal neurobehavioral development: associations with socioeconomic class and fetal sex. Dev. Psychobiol. 33, 79–91 (1998).

Field, T. Prenatal depression risk factors, developmental effects and interventions: a review. J. Pregnancy Child Health. 4, 301 (2017).

Merced-Nieves, F. M., Dzwilewski, K. L. C., Aguiar, A., Lin, J. & Schantz, S. L. Associations of prenatal maternal stress with measures of cognition in 7.5-month-old infants. Dev. Psychobiol. 63, 960–972 (2020).

Merced-Nieves, F. M. et al. Association of prenatal maternal perceived stress with a sexually dimorphic measure of cognition in 4.5-month-old infants. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 77, 106850 (2020).

Bergman, K., Sarkar, P., O’Connor, T. G., Modi, N. & Glover, V. Maternal stress during pregnancy predicts cognitive ability and fearfulness in infancy. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 46, 1454–1463 (2007).

Adams-Chapman, I., Bann, C. M., Vaucher, Y. E., Stoll, B. J. & Eksni, C. Association between feeding difficulties and language delay in preterm infants using Bayley scales of infant development. J. Pediatr. 163, 680 (2013).

Wolthuis-Stigter, M. I. et al. The association between sucking behavior in preterm infants and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years of age. J. Pediatr. 166, 26 (2015).

Glover, V. Maternal depression, anxiety and stress during pregnancy and child outcome; what needs to be done. Best. Pr. Res Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 28, 25–35 (2014).

Heinrichs, M. et al. Effects of suckling on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responses to psychosocial stress in postpartum lactating women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 4798–4804 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank our ECHO colleagues; the medical, nursing, and program staff; and the children and families participating in the ECHO cohorts. We also acknowledge the contribution of the following ECHO program collaborators: ECHO Components—Coordinating Center: Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, North Carolina: Smith PB, Newby KL, Benjamin DK.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) program, Office of The Director, National Institutes of Health, under award numbers U2COD023375 (Coordinating Center), U24OD023382 (Data Analysis Center), U24OD023319 (PRO Core), and U2COD023375 (OIF). Dr. Aung’s work was supported by NIH award number P30ES030284. Research on the ECHO-PROTECT cohort was supported by the Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Center (NNIEHS P42ES017198, P50ES026049, and UH3OD023251), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) grant R836155, the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Program (NIH OD023251), and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, award number U54MD007600. Research on the IKIDS cohort was supported by the Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Center (NIEHS P01 ES022848 and USEPA RD83543401) and the ECHO Program (NIH OD023272).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

E.Z. and A.A. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: E.Z. and A.A. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: E.Z. and A.A. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: E.Z., A.A., S.D.G., and M.T.A. Review of the original draft: all authors. Statistical analysis: M.T.A. and S.D.G. Obtained funding: E.Z., A.A., S.L.S., A.N.A., J.F.C., and J.D.M. Administrative, technical, or material support: E.Z., A.A., S.L.S., and A.N.A. Supervision: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent statement

Written informed consent was obtained from participants during pregnancy and at the child’s first assessment.

Disclaimer

The content and views expressed here are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the EPA, NIEHS, NIH, or National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, or Duke University (which manages Drs. Zimmerman and Aguiar’s NIH award number U2COD023375).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zimmerman, E., Aguiar, A., Aung, M.T. et al. Examining the association between prenatal maternal stress and infant non-nutritive suck. Pediatr Res 93, 1285–1293 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01894-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01894-9

This article is cited by

-

Impact of intrapartum oxytocin administration on neonatal sucking behavior and breastfeeding

Scientific Reports (2024)