Abstract

Background

Biliary atresia (BA) is a severe pediatric biliary disorder characterized by the progressive obstruction of liver bile ducts. In the absence of treatment, fibrosis advances rapidly in most affected children. Despite the identification of various factors contributing to fibrosis progression, comprehensive investigations into the microenvironmental alterations within the liver are still scarce.

Methods

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) was conducted on two normal tissues adjacent to liver tumors, two choledochal cyst liver tissues, and four BA liver tissues. This analysis, combined with spatial localization data, elucidated the heterogeneity of the livers affected by BA. Ultimately, a diagnostic model for BA was developed, leveraging high-resolution fibrosis-related gene signatures.

Results

We identified scar-associated macrophages (SAMs) originating from monocytes, which played a pivotal role in fibrosis progression and may be implicated in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of biliary epithelial cells (BECs). Furthermore, the hub genes CD96, EVL, S100A6, and S100A11 were found to be upregulated in SAMs and regulatory T cells (Tregs), aiding in the diagnosis of BA.

Conclusion

SAMs and BECs not only exhibited a pro-fibrotic phenotype but also co-localized within fibrotic regions. Their interaction may facilitate the activation of EMT, highlighting a potential therapeutic target for BA treatment.

Impact

-

Analysis of the immune landscape: Through single-cell and spatial transcriptomic techniques, the paper reveals the complex immune landscape associated with BA fibrosis.

-

Exploration of new therapeutic targets: This paper reveals that SAMs can promote the progression of liver fibrosis by regulating the EMT conversion of BECs, opening up a new therapeutic approach.

-

Application of diagnostic markers: The paper identifies biomarkers that may improve early diagnostic accuracy and postoperative prognosis and recommends their incorporation into clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biliary atresia (BA) is a severe fibroinflammatory disease affecting both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts.1 It is characterized by rapid fibrosis progression and subsequent liver failure.2 The disease is thought to be driven by multiple factors, including inflammation, genetic predisposition, and immune dysregulation. However, the precise mechanisms underlying its abnormal fibrotic progression remain unclear.3 Further research is needed to elucidate the heterogeneous cellular alterations, differentiation dynamics, and complex interactions within the BA liver microenvironment.

Single-cell RNA (scRNA) sequencing is a highly sensitive, accurate, and efficient method for sorting and sequencing individual cells. However, its limitation in capturing the spatial context of cells is addressed by spatial transcriptomics (ST), which provides deeper insights into cellular distribution within tissues. A recent scRNA-seq study identified several key features in BA livers, including macrophage hypo-inflammation, impaired Kupffer cell function, cytotoxic T cell expansion, and a deficiency of CX3CR1+ effector T and NK cells.4 Additionally, significant cellular heterogeneity was observed in the BA liver microenvironment.5 Our study further identified aberrant proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) activation in Bile duct epithelial cells (BECs), as well as the heterogeneity of scar-associated macrophages (SAMs). These findings contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the microenvironmental alterations in BA livers.

Kasai portoenterostomy (KPE) surgery is effective in restoring biliary drainage in BA. Research indicates that early KPE intervention is crucial, making the differentiation of BA from other cholestatic diseases essential.6,7 While MMP7 is a promising non-invasive biomarker for BA, its clinical utility is limited by the lack of standardized protocols.8,9 In this study, we employed a combined approach of ST and scRNA-seq to construct, for the first time, a four-gene diagnostic model for BA with higher resolution. Additionally, these four genes also serve as predictors for native liver survival.

In this study, we integrated scRNA-seq and ST techniques to reveal microenvironmental changes across different stages of BA fibrosis. Pseudo-time and Cell Chat analyses indicated that SAMs may play a role in promoting EMT activation in BECs and were co-localized in fibrotic regions. Lastly, we developed a high-resolution fibrosis score to aid in the diagnosis of BA.

Methods

Figure S1 shows the flowchart of this study.

Data collection and sample collection

The cohort consisted of four children with type III BA, two with choledochal cysts (CC), one with hepatoblastoma, and one with hemangioma who were treated at the Department of General Surgery of Tianjin Children’s Hospital between 2023 and 2024. All children received surgical treatment from the same team. Clinical and pathologic data were obtained from histopathology reports and electronic records of the Department of General Surgery, Tianjin Children’s Hospital. Fibrosis grading using the METAVIR scoring method. Deep scRNA-seq was performed on cells in liver tissues of BA, CC, and in normal tissues adjacent to liver tumors (NC). Meanwhile, deep ST sequencing was performed on the fibrosis Grade IV BA liver tissues and normal tissues adjacent to hepatoblastoma. Sequencing information and clinical information for these samples were presented in Table S1.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Children’s Hospital (2022-SYYJCYJ-008) and informed consent was obtained from the legal guardian of each patient. The livers of patients in the BA and control groups were collected during the procedure.

Single-cell suspension preparation and quality control: Tissue samples are dissociated into single-cell suspensions using sCelLiVE™ Tissue Dissociation Solution, and the cells are diluted to a suitable concentration of 2.5–3.5 × 105 cells/mL.

Single cell isolation and labeling: The cell suspension is injected into the SCOPE-chip™ microfluidic chip, and single cells are separated according to the principle of “Poisson distribution”. After cell lysis, the magnetic beads with unique Barcode and UMI tags capture the mRNA by binding to the poly(A) tails on the mRNA, labeling the cells and mRNA.

Reverse transcription and amplification: Collect the magnetic beads in the microarray, reverse transcribe the mRNA captured by the magnetic beads into cDNA and amplify it.

Single-cell sequencing library construction: The cDNA is fragmented and ligated to construct a sequencing library for Illumina sequencing platform.

The gene microarray data (GSE15235,10 GSE46960,11 GSE122340,12 GSE159720,13 GSE221346, GSE16365014 and GSE17618915) were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. We provide information about each sample in the supplementary materials (Table S2).

ST barcoded microarray slide information

ST experiments were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (10x Genomics). Briefly, HE-stained sections of 5 μm thick paraffin block samples of liver tissue were taken, selected areas were incubated with probes, and then transferred to 10x air-transferred slides by the CytAssist system for capture and library construction.

ST barcoded microarray processing

The batch effect was removed using the “tidyverse” package (version 1.3.2) and the “SCTransform” function.16 To improve ST resolution, the top 30 highly expressed genes in each cluster from scRNA-seq data originating from the same sample were extracted. These genes were scored by the “AUCell” method in ST barcoded microarray.

The scRNA-seq analysis

First, doublets were removed from the samples by the “DoubletFinder” package (version 2.0.3).17 Both sets of cells were normalized with the “Seurat” package (version 4.1.1)18 with parameters nFeature_RNA ≥ 200, nCount_RNA ≥ 500, log10FeaturePerUMI ≥ 0.8, and percent_mito ≤ 15. Detailed cell counts for the samples can be accessed in Table S3.

Afterwards, the batch effect was removed and scRNA-seq data were integrated using the “tidyverse” package (version 1.3.2) and the “SCTransform” function.16 Unified manifold approximation projection (UMAP) method was used as a visualization method for cell clustering.19 To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), we used the “FindAllMarkers” function in Seurat. The Benjamini-Hochberg method estimated the false discovery rate (FDR).20 The criterion for selecting DEGs was an FDR value of less than 0.05. The “clusterProfiler” package (version 4.6.2) and “GSVA” package (version 1.46.0) was used to compute cell-enriched pathways.21 In order to characterize the correlation between cells and fibrosis, “AddModuleScore” function22 was performed to quantify the fibrosis score of each cell through the 33 liver fibrosis-specific matrisome genes (LFMGs) identified in the study of Hong You et al.23. The Kupffer score and (marrow monocyte-derived macrophages) MoMF score for MPs (Mononuclear phagocyte system) were also collected.24

Analysis of tissue heterogeneity

To quantify the heterogeneity of cell types in different tissues, we compared the observed and expected number of cells for each cluster in each tissue according to the following previously described formula, Ro/e = (observed/expected), where the expected number of cells of cell clusters in a given tissue was calculated by Chi-square test.24 If Ro/e > 1.5, we assume a weak positive (+) enrichment of a cell cluster in the given tissue. If Ro/e > 3, the identification is positive (++); Ro/e > 5, it is a strong positive (+++).

Single-cell pseudo time analysis

We used “monocle” to analyze the lineage differentiation of cell subtypes with potential developmental relationships.25

Single-cell interaction analysis

The “CellChat” package (version 1.5.0)26 was used to compute intercellular communication relationships and visualized with the “patchwork” package (version 1.1.2).

Meta-analysis of public datasets

To further validate BA liver cell heterogeneity, we performed scRNA deconvolution analyses of the GSE46960, GSE122340, GSE159720, and GSE221346 cohorts via the Cibersort website (https://cibersortx.stanford.edu/). Hedges’g is mainly used to calculate standardized mean difference in small studies, thus integrating the data through meta-analysis and making the conclusions more reliable.27 When I2 < 0.5, the fixed effects model is chosen, and when I2 ≥ 0.5, the random effects model is chosen.

Identifying molecular models of fibrosis

Firstly, through the “SPARK” package, screening and spatial localization of genes with significant correlation existed.28 After that, the fibrosis region highly expressed genes, BA highly expressed genes in ST and BA highly expressed genes in scRNA were screened by “FindAllMarkers” function respectively. The overlapping genes were taken into account including Lasso regression, Neural Network (MLP), Logistic Regression (LR), Linear discriminant analysis, Quadratic discriminant analysis, k-Nearest Neighbor, Decision tree, Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Ridge Regression (RR), Elastic Net regression (ENR), Support vector machine, Grandient Boosting Machine, stepwise LR and Naive Bayesian algorithm. Finally, Lasso regression combined with RF achieved the best diagnostic results. We also validated the predictive effect of the integration of the four hub genes of the model on BA autologous liver survival.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed through the use of R software (version 4.1.3). Data conforming to the normal distribution were evaluated using the unpaired Student’s t-test and data conforming to the non-normal distribution were evaluated using the Wilcoxon test, and the statistical significance threshold was set at p < 0.05. Spearman correlation analysis for two sets of normal quantitative data.

Results

The scRNA-seq analysis

First, eight scRNA-seqs were integrated for a total of 58,850 cells, including T and NK cells, B cells, MPs, EndoCs, proliferating cells, hepatocytes, Plasma cells (PCs), EpiCs, neutrophils and fibroblasts (Fig. 1a, b). Total 14,905 cells after integration of GSE163650, including T and NK cells, B cells, MPs, neutrophils, other cells, PCs, and proliferating cells (Fig. S2A, B).

a Cellular markers were used to identify and verify the distribution of cellular subpopulations. b UMAP projections for each cell of the scRNA-seq cohort. c UMAP projections showing the distribution of BA (Fibrosis ≤ 2), BA (Fibrosis > 2), CC and NC single cells. d Percentage difference between BA(Fibrosis ≤ 2), BA(Fibrosis > 2), CC and NC cell clusters. e Percentage difference between BA, CC, and NC cell clusters. f 33 LFMGs were used to assess Fibrosis Score for BA (Fibrosis ≤ 2), BA (Fibrosis > 2), CC and NC. g Differences in Fibrosis Score of each cell cluster. scRNA-seq single-cell RNA sequencing, UMAP Uniform manifold approximation and projection, BA biliary atresia, CC Choledochal cysts, NC Normal control, LFMGs liver fibrosis-specific matrisome genes.

Cellular annotations were taken for marker genes and references in Table S4. The cell occupancy ratios showed an increase in MPs infiltration and a decrease in EndoCs infiltration with increasing fibrosis. While hepatocytes and EpiCs showed an increase and then a decrease (Fig. 1c, d). The percentage of T and NK cells, MPs, hepatocytes, and EpiCs was increased in BA compared to NC. While the percentage of B cells, EndoCs, and neutrophils decreased (Figs. 1e; S2C). Consistent with clinicopathological observations, BA in the high fibrosis grade group had the highest fibrosis scores (Fig. 1f). MPs, endothelial cell, EpiCs, and fibroblasts had significantly higher fibrosis scores (Figs. 1g; S2D).

BECs exhibit EMT activation and pro-fibrotic phenotypes

In the present study, we found that epithelial alterations play an important role in the progression of BA. EpiCs and hepatocytes were reclusttered into 10 clusters (Fig. S3A). The starting point of cell differentiation was determined based on differentiation trajectories and marker genes of the EpiCs (Fig. S3B). Cluster 0 was labeled as BECs. Clusters 1, 3, 4, and 5 were labeled as hepatocytes. The remaining cells were classified as bipotent, hepatocyte-mediated bipotent and bile duct-mediated bipotent based on differentiation trajectory (Figs. 2a; S3C). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis showed that BECs were associated with bile secretion and hepatocytes with metabolism (Fig. S3D, E).

a UMAP projection showing the distribution of 1603 EpiCs from the Tianjin Children’s Hospital scRNA-seq cohort after dimensionality reduction clustering. b Differences in Fibrosis Score of five cell clusters. c Percentage difference between BA(Fibrosis ≤ 2), BA(Fibrosis > 2), C,C and NC cell clusters. d Percentage difference between BA, CC, and NC cell clusters. e 4 LFMGs change heterogeneity with cell track expression. f Differential GSVA enrichment analysis of BECs between BA and controls. g Volcano map showing results of differential analysis between BECs and other cells. h Venn diagram showing overlapping genes of EMT-related signaling pathway genes from GSEA website and genes up-regulated by BECs. i ST analysis reveals heterogeneity of five cell clusters localized in the liver. BECs Bile duct epithelial cells, EMT epithelial-mesenchymal transition, UMAP Uniform manifold approximation and projection, EpiCs epithelial cells, BA biliary atresia, CC Choledochal cysts, NC Normal control, LFMGs liver fibrosis-specific matrisome genes, GSVA Gene set variation analysis, ST Spatial transcriptome.

Further functional analysis revealed elevated fibrosis scores in BECs, bipotent cells, and bile duct-mediated bipotent cells (Fig. 2b). With increasing levels of fibrosis, BECs and bipotent cells increased, while hepatocytes and hepatocyte-mediated bipotent cells decreased (Fig. 2c, D). Besides that, with the differentiation of bipotent cells to BECs, the fibrosis-related genes ANXA2, CXCL6, MMP7 and S100A6 showed a significant elevation in BA compared to CC and NC (Fig. 2e). Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) showed that fibrosis-related pathway EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION were up-regulated in hepatocytes and cholangiocytes in BA compared to CC and NC (Fig. 2f). In addition, there were overlapping genes for up-regulated genes of BECs and EMT-related genes in BA (Fig. 2g, h). Combined with ST analysis, we further demonstrated the correlation between BECs and BA fibrosis. BECs were significantly enriched in fibrotic areas. In contrast, hepatocytes were significantly enriched in the NC (Fig. 2i). In conclusion, aberrant activation of EMT and upregulation of fibrotic gene expression in BECs may promote fibrotic progression in BA.

In addition to this, we analyzed the heterogeneity of EndoCs and fibroblasts. Cells were classified as liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), vein ECs, artery ECs, and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) based on genetic markers (Fig. S4A, B). Decreased LSECs infiltration in BA but increased percentage of artery ECs and vein ECs (Fig. S4C, D). HSCs showed higher fibrosis scores, while HSCs, arterial ECs, and venous ECs were enriched in fibrotic areas (Fig. S4E, F). We observed abnormal proliferation of arteries and veins in areas of fibrosis.

Partial BECs have a tendency to differentiate towards HSCs

To further demonstrate EMT activation, we subjected hepatocytes, EpiCs, and HSCs to pseudo time analysis. Interestingly, partial BECs have a phenotype of conversion to HSCs, which does not occur in hepatocytes (Fig. 3a). This cluster of cells was identified as EMT-associated BECs that may have undergone EMT activation. Pseudo time difference analysis revealed that differential gene changes in cluster 2 converged with the differentiation of EMT-associated BECs (Fig. 3b). Compared to other BECs, fibrosis-related genes were specifically expressed in EMT-associated BECs, including EGR1,29 IGFBP7,30 ITGB131 and TPM132 (Fig. 3c). GO enrichment analysis revealed that cluster 2 differential genes were associated with fibrotic pathways such as wound healing and myofibril assembly (Fig. 3d). EMT-related genes CDH2, CALU, CDH6, COPA, CALD1 and CADM1 are up-regulated in EMT-associated BECs compared to other BECs (Fig. 3e). In conclusion, EMT-associated BECs and HSCs have similar phenotypes, which may be a key process in their promotion of fibrosis.

a Pseudotime analysis of BECs, hepatocytes, other EpiCs, and HSCs. b Heatmap of pseudotime differential gene analysis. c Expression of cluster 2 fibrosis-related genes in EMT-associated BECs. d GO enrichment analysis of cluster 2 specific genes. e Compared with other BECs, EMT-related genes were up-regulated in EMT-associated BECs. BECs Bile duct epithelial cells, HSCs Hepatic stellate cells, EpiCs epithelial cells, EMT epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

SAMs play a key role in liver fibrosis progression

To further analyze which cells play a key role in MPs with high fibrosis scores, we derived 19,728 MPs and classified them into 10 clusters based on marker genes, including CD14+Mon1, CD16+Mon2, TIMD4+Kupffer cells (KCs), TREM2+SAMs, CD300E+intMon, CD1E+cDC2, IL1B+Pi Mon, FCN1+Monlike-Mac, IL3RA+pDC and CLEC9A+cDC1 (Figs. 4a; S2H, I; S5A). GO enrichment analysis showed that CD14+Mon1 and CD16+Mon2 regulated cell chemotaxis and migration (Fig. S5B, C). TIMD4+KC plays a role in the regulation of innate immunity and viral clearance (Fig. S5D). TREM2+SAMs play roles such as regulating apoptosis and CD300E+intMon promotes cell adhesion (Fig. S5E, F). In addition, IL1B+Pi Mon has functions such as regulating the NFKB signaling pathway and Th17 cell differentiation (Fig. S5G).

a UMAP projection showing the distribution of 19,728 myeloid cells in the Tianjin Children’s Hospital scRNA cohort after dimensionality reduction clustering. b Percentage difference between BA(Fibrosis ≤ 2), BA(Fibrosis > 2), C,C and NC cell clusters. Percentage difference between BA, CC, and NC cell clusters. c Differences in Fibrosis Score of 8 scRNA samples and 10 myeloid cell clusters. d Differences in MoMF Score of 8 scRNA samples and 10 myeloid cell clusters. e Differences in Kupffer Score of 8 scRNA samples and 10 myeloid cell clusters. f CD14+Mon1, TIMD4+SAMs, CD300E+intMon, and IL1B+Pi Mon were enriched in fibrotic regions. SAMs scar-associated macrophages, UMAP Uniform manifold approximation and projection, BA biliary atresia, CC Choledochal cysts, NC Normal control, scRNA-seq single-cell RNA sequencing, MoMF marrow monocyte-derived macrophages.

The proportion of TREM2+SAMs and CLEC9A+cDC1 were increased in BA compared to NC (Fig. 4b, S2J). Elevated fibrosis scores in CD14+Mon1, TREM2+SAMs, CD300E+intMon, and IL1B+Pi Mon (Fig. 4c). To understand the origin of subpopulations of MPs, this study defined macrophages derived from Kupffer score or MoMF score based on reported markers. MoMF scores were higher for CD14+Mon1, TREM2+SAMs, CD300E+intMon, and IL1B+Pi Mon. Meanwhile, based on the original report, it was hypothesized that TREM2+SAMs may act as mature cells and play a pro-fibrotic role (Fig. 4d, e).33 The ST analysis further revealed that CD14+Mon1, TREM2+SAMs, CD300E+intMon, and IL1B+Pi Mon were enriched in fibrotic areas (Fig. 4F). In conclusion, TREM2+SAMs in MPs were identified as a key cluster promoting fibrosis.

SAMs are derived from monocytes and are associated with EMT activation

Pseudo time analysis revealed different differentiation trajectories of SAMs between and within groups (Fig. 5a). Expression of fibrosis-associated genes ANXA2, LGALS3, S100A8, SPP1 and TGFB1 was progressively elevated in BA with progressive differentiation of monocytes to SAMs (Fig. 5b). However, we observed a progressive increase in CD9 and TREM2 expression accompanied by a progressive decrease in IL1B expression (Fig. 5b). This further suggests a pro-inflammatory to pro-fibrotic phenotypic switch in BA different from NC. Furthermore, GSVA enrichment analysis showed that four cell types in BA were upregulated in fibrosis-related pathways EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION compared to NC and CC (Fig. 5c). Meanwhile, there was a significant correlation between KRT18 and the marker genes of SAMs (CD9 and TREM2) in GSE46960, GSE122340 and GSE1523 cohorts (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5d). The key gene for EMT, CDH2, showed the same strong correlation (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5d). Therefore, SAMs are not only a key cluster of pro-fibrosis but may also be involved in EMT activation.

a Pseudotime analysis of CD14+Mon1, TIMD4+SAMs, CD300E+intMon and IL1B+Pi Mon. b Changes in expression of fibrosis-related genes, marker genes for SAMs and marker genes for Pi Mon following pseudotime. c GSVA differential enrichment analysis of IGHM+naïve B, CD19+T1B, IGHD+T2B, and MME+Immature B in BA and control groups. d Correlation analysis of signature genes of SAMs (CD9 and TREM2) and KRT18, CDH2 in GSE46960, GSE122340, and GSE15235 cohorts. SAMs scar-associated macrophages, EMT epithelial-mesenchymal transition, GSVA Gene set variation analysis, BA biliary atresia.

Immunoregulatory effects of Treg and Th1 are associated with liver fibrosis

We derived 20,195T and NK cells for analysis. A total of 11 cell types were labeled according to markers for T and NK cells, including NCAM1+NK cells, SKAP1+T cells, FYN+T cells, SELL+T cells, ZNF683+T cells, FCGR3A+NK cells, CCL5+T cells, LEF1+T cells, MKI67+T cells, IFNG+Th1 cells and FOXP3+Treg cells (Table S4; Figs. S3E, F; S6A). With increasing fibrosis, the percentage of NCAM1+NK cells gradually decreased, while ZNF683+T cells, CCL5+NKT cells, IFNG+Th1 cells, and FOXP3+Treg cells gradually increased (Figs. S3G; S6B). Besides that, the percentage of SKAP1+T cells, IFNG+Th1 cells and FOXP3+Treg cells was increased in BA compared to NC (Figure S6C). The ST indicated that IFNG+Th1 cells and FOXP3+Treg cells were enriched in fibrotic areas (Fig. S6D). These results suggest that Treg and Th1 may promote fibrosis by exerting immunomodulatory functions in BA.

We derived 7844 B cells and 783 PCs. A total of 7 clusters were obtained after performing the reclustering annotation, including IGHM+naive B, CD19+T1B, RAG1+Pre B, IGHD+T2B, MME+Immature B, IGHA+PCs, and IGHG+PCs (Fig. S6E). Similar to previous studies, we found an increased percentage of RAG1+Pre-B, IGHD+T2B, and IGHG+PCs in BA compared to NC and CC (Fig. S6F, G).34

Validation of meta-analysis of public data

Bulk sequencing data with both BA and controls were included for deconvolution analysis of all single-cell species (Fig. S7). Results of meta-analysis showed that BECs, ZNF683+T cells, IFNG+Th1 cells, TREM2+SAMs, CD14+Mon1, and CD19+T1B infiltrated increased in BA samples. Hepatocytes, TIMD4+KC, Neutrophils, and IGHG+PCs were less infiltrated in BA. This further confirms the important role of SAMs and BECs in the occurrence and development of BA.

Intercellular interaction

We selected fibrosis-associated immune cells, BECs, and HSCs for cell interaction analysis. Increased PERIOSTIN, CHEMERIN, FGF, GAS, ANGPT, PARs, IL6, TGFb, PTN ligand-receptor interactions in BA compared to CC and NC (Fig. 6a). HSCs, BECs, CD14+Mon1, TREM2+SAMs, CD300E+intMon, IL1B+Pi Mon, FOXP3+Treg and IFNG+Th1 interactions are enhanced (Fig. 6b). The loop diagram also demonstrates that CD14+Mon1, TREM2+SAMs, and CD300E+intMon not only have increased interactions with HSCs but also enhanced interactions with BECs (Fig. 6c). TREM2+SAMs can act on BECs via SPP1-(ITGAV + ITGB1) and AREG-(EGFR + ERBB2), which may promote the abnormal proliferation of BECs (Fig. 6d). In turn, BECs may also promote TREM2+SAMs complement activity via C3-(ITGAX + ITGB2) (Fig. 6e). Several studies found that both SPP1-(ITGAV + ITGB1) and AREG-(EGFR + ERBB2) promoted EMT activation.35,36,37 In addition, TREM2, CD9, and KRT19 co-localized in the fibrotic zone, further demonstrating the strong interactions between SAMs and BECs (Fig. 6f). ST analysis also showed that C3-(ITGAX + ITGB2), SPP1-(ITGAV + ITGB1), TGFB signaling pathway, and FGF1-FGFR3 co-localized in fibrotic regions in BA compared to NC (Fig. S8A–E). Therefore, SAMs may promote EMT activation in BECs to exert the pro-fibrotic effect, which may be a potential basis for the rapid progression of BA fibrosis.

a Histogram of differences in cellular communication between BA and controls. b Heatmap of differences in the number and intensity of cellular effects between BA and controls. c Chord plot of the number of cellular actions between BA and controls. d, e Dot plot of the interaction between BECs and fibrosis-associated cells. f Analysis of co-localization of TREM2, KRT19, and CD9 on the ST analysis. g Heatmap showed the CXCL pathway difference between the control group and the BA group. BECs Bile duct epithelial cells, HSCs Hepatic stellate cells, BA biliary atresia.

In addition, Treg and Th1 cells may promote the convergence of SAMs towards fibrous regions via the CXCL signaling pathway (Fig. 6g).

External validation of SAMs facilitates the occurrence of EMT in BECs

The single-cell dataset GSE176189 was used for external validation. After quality control, a total of 106,897 cells were used for subsequent analysis. To further validate the interaction between SAMs and BECs, we performed secondary annotation only on the MPs. Eventually, 16 subgroups were identified (Fig. S9A, B). Compared to CC, the EMT signaling pathways in BECs, FCN+Mon, and TREM2+SAMs were significantly upregulated in BA (Fig. S9C–E). Similarly, cell communication analysis showed that the interaction between BECs and SAMs was significantly enhanced in BA (Fig. S9F). Compared to CC, in BA, SAMs significantly upregulated their influence on BECs through the SPP1-ITGAV/ITGB1 signaling pathway (Fig. S9G). In summary, these results further support that SAMs can promote EMT in BECs through the SPP1-ITGAV/ITGB1 signaling pathway.

Identifying molecular models of fibrosis

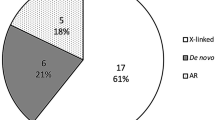

SPARK identifies spatial expression models of genes by detecting highly variable genes in space. A total of 9668 genes were screened by SPARK for differences in spatial location in BA liver (adjP-value < 0.05). A total of 6385 highly expressed genes in the fibrotic region of the ST (adjP-value < 0.05). A total of 664 genes were highly expressed in BA in the ST (adjP-value < 0.05) and 248 genes were highly expressed in BA in the scRNA (adjP-value < 0.05). A total of 16 overlapping genes were further screened (Fig. 7a). Among 15 machine learning algorithms individually or in combination, we chose Lasso regression incorporating RF as the best algorithm, including a total of four hub genes, namely S100A6, S100A11, CD96 and Enah/Vasp-Like (EVL) (Fig. 7b). The fibrosis model constructed for the four hub genes had an Area under the cure (AUC) of 1.000 for the Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) in the training cohort GSE46960 and 0.839 and 0.879 for the ROC in the validation cohorts GSE122340 and GSE221346, respectively (Fig. 7c–e). Meanwhile, these four genes could divide the 45 BA samples of GSE159720 into high and low expression groups (Fig. 7f). Kaplan-Meier curves observed that the high expression group showed poorer autologous liver survival (Fig. 7g).

a Venn diagram showing overlapping genes identified by SPARK as highly variable, highly expressed in fibrotic regions, spatial BA-related genes, and single-cell BA highly expressed genes. b Integration of 15 machine learning approaches for hub genes screening of overlapping genes for BA diagnosis. c–e ROC curves demonstrating the diagnostic efficacy of four genetic models for BA in GSE46960 (train set), GSE122340 (test set), and GSE221346 (test set). f Four genes classify GSE15235 into two subgroups, high and low expression. g Differences in autologous liver survival in two subpopulations of GSE15235. BA biliary atresia, ROC Receiver operating characteristic curve.

S100A6, S100A11, CD96, and EVL are all expressed at elevated levels in grade III and IV fibrosis of BA. Of these four genes, CD96 and EVL are predominantly expressed in T and NK cells (Fig. S10A, B). CD96 expression was elevated in SKAP1+T cells, LEF1+T cells, and FOXP3+Treg T cells compared to controls. EVL expression was elevated in SKAP1+T cells, MKI67+T cells, and IFNG+Th1 cells compared to controls. S100A11 and S100A6 are predominantly expressed in MPs (Fig. S10C, D). S100A11 expression was elevated in TIMD4+KC cells, TREM2+SAMs cells, and FCN1+Monlike-Mac cells compared to controls. S100A6 expression was elevated in TIMD4+KC cells and TREM2+SAMs cells compared to controls. Correlation analysis of the four external datasets showed that these four genes and fibrosis-related genes remained strongly correlated (Figure S10E,F). Finally, we summarized the mechanism of the process of fibrosis in BA discovered in this study (Fig. 8).

Discussion

Studies have shown that fibrosis in BA progresses rapidly, often leading to early-stage cirrhosis; however, the precise mechanisms remain unclear. Yuxia Zhang et al. were pioneers in using single-cell immuno-mapping to highlight the potential of B-cell-targeted therapies in mitigating liver inflammation.4 Subsequently, Shan Zheng et al. described immune cells that may be involved in fibrosis progression.5 Our study focuses on fibrotic region-specific cells and the highly expressed genes associated with fibrosis promotion and predictive value. We observed abnormal proliferation of BECs in fibrotic regions, potentially regulated by CD14+Mon1, TREM2+SAMs, CD300E+intMon, and IL1B+Pi Mon. Additionally, IFNG+Th1 and FOXP3+Treg were enriched in fibrotic regions, promoting the chemotaxis of TREM2+SAMs. Importantly, by integrating ST with scRNA sequencing, we developed high-resolution diagnostic models for BA, with four genes in the model also showing predictive value for native liver survival.

In BA, BECs exhibit both damage and proliferative repair, which may be linked to disease progression. The accumulation of interferon-responsive neutrophils has been shown to induce BEC apoptosis in BA.38 Additionally, direct viral actions can also result in BEC apoptosis.39,40 The repair process of BECs is characterized as non-functional, as evidenced by the downregulation of genes involved in ciliary signaling.41,42 We observed advanced fibrosis with BEC infiltration in fibrotic regions, accompanied by a marked upregulation of ANXA2, CXCL6, MMP7, and S100A6 as BECs matured. Notably, hepatocyte infiltration was predominant in the early stages of BA fibrosis, while BEC infiltration became more pronounced in the later stages, suggesting that BECs may serve as the initiating factor in fibrosis.2

In this study, we observed that a subset of BECs in BA underwent abnormal EMT, acquiring a mesenchymal phenotype. Previous research has identified abnormal activation of the Hedgehog signaling pathway in BA, which, in turn, stimulates EMT in BECs.43 Our previous work also demonstrated that EGF can promote EMT in BECs.44 However, there remains a lack of comprehensive studies exploring the role of EMT in promoting fibrosis. Our current findings, derived from scRNA-seq and ST sequencing, suggest that SAMs may act as initiators of EMT in BECs. The interaction between SAMs and BECs primarily occurs through the SPP1-(ITGAV + ITGB1) and AREG-(EGFR + ERBB2) pathways. SPP1-(ITGAV + ITGB1) facilitates cell adhesion and proliferation, while AREG-(EGFR + ERBB2) supports epithelial cell damage repair.45,46,47 Notably, SPP1 has been shown to induce EMT in alveolar epithelial cells in studies of lung fibrosis.37 In lung adenocarcinoma research, SPP1 was found to promote the expression of COL11A1,48 and in colorectal cancer studies, SPP1 was implicated in inducing EMT.49 Additionally, AREG has been shown to promote EMT activation in oral epithelial cells.50 EGFR, as an epidermal growth factor receptor, is known to enhance cell proliferation.51 The strong interactions between SAMs and BECs may represent a novel avenue for future research on BA fibrosis and could inform the development of targeted therapies.

Macrophages infiltrate and accumulate extensively in the livers of children with BA, and studies have shown that depletion of these macrophages can mitigate fibrosis.52,53 In this context, CD14+Mon1, TIMD4+SAMs, CD300E+intMon, and IL1B+Pi Mon have been implicated in fibrosis progression. Pseudo time analysis indicated that TIMD4+SAMs are derived from CD14+Mon1, CD300E+intMon, and IL1B+Pi Mon. Fibrosis-associated genes such as ANXA2, LGALS3, and SPP1 were progressively upregulated during the maturation of TIMD4+SAMs. N.C. Henderson et al. demonstrated that SAMs are elevated in liver fibrosis and exert a pro-fibrotic effect.33 Concurrently, MMP9+neutrophils in the liver, which participate in TGF-β1 activation, facilitate the differentiation of SAMs.54 Treg cells have immunomodulatory roles, and their dysfunction is linked to autoimmune mechanisms in BA. Studies have reported reduced peripheral Treg proportions, along with a decrease in both the number and function of hepatic Tregs in the RRV-induced BA mouse model.55,56,57

CD96, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, plays a role in regulating NK cell effector function and metastasis.58 Consistent with previous studies, CD96 is primarily expressed on the surface of T and NK cells.59 However, whether CD96 acts as an inhibitor or activator of NK and T cells remains controversial.60 In hepatocellular carcinoma, CD96+NK cells predominantly express TGF-β and IL-10, with reduced expression of IL-15, perforin, T-bet, and granzyme B.60 B. Jin et al. observed that serum sCD96 levels were significantly elevated in patients with cirrhosis due to chronic viral hepatitis B, though the underlying mechanism remains unclear.61 In our study, we found that CD96 was primarily expressed in fibrotic regions during the advanced stages of hepatic fibrosis, suggesting a potential pro-fibrotic role. EVL, a member of the Ena/VASP family, is involved in actin cytoskeleton reorganization, cell migration, contractile ring formation, and intercellular attachment.62 Our findings indicate that EVL is predominantly expressed in T and NK cells, which may facilitate their migration to fibrotic regions.63 S100A6 and S100A11, both members of the S100 protein family, have been closely associated with fibrosis in several studies. S100A6 serves as a cellular marker for activated fibroblasts and promotes the proliferation of activated HSCs, thereby contributing to fibrosis.64,65 Additionally, S100A6 was found to be overexpressed in intrahepatic cholangiocytes of BDL mice.66 In hepatocellular carcinoma, overexpression of S100A11 has been shown to promote inflammation and fibrosis in vivo.67 S100A11 activates HSCs and the fibrotic process by regulating the deacetylation of Smad3 in the TGF-β signaling pathway.68 These findings suggest that S100A6 and S100A11 play a promotive role in liver fibrosis. In our study, we observed that S100A6 and S100A11 were predominantly expressed in MPs, with significantly higher expression in TREM2+SAMs.

In addition, S100A6 and S100A11 also exhibit pro-inflammatory effects. Studies have found that in patients with systemic sclerosis, S100A6 may be an upstream molecule in pulmonary fibrosis, innate immunity, and vascular injury.69 S100A6 can also promote B cell infiltration, exacerbating autoimmune encephalitis.70 Fengguang Yang et al. discovered that S100A6 regulates nucleus pulposus cell apoptosis via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.71 S100A11 can inhibit the viability of nasal mucosal epithelial cells, promoting apoptosis and inflammation.72 In rheumatoid arthritis, extracellular S100A11 increases the secretion of IL-6 and TNF by neutrophils.73 The expression of the S100A11 gene promotes IL-29 expression, which inhibits vaccinia virus replication.74 Increased expression of S100A6 and S100A11 may jointly enhance the inflammatory response in the livers of children with BA.

This study has several limitations. First, despite extensive validation using publicly available data, our analysis was based on only eight single-cell samples and two ST samples, which may have introduced bias. We plan to conduct further experimental validation to address this. Secondly, due to the absence of IGHM, IGHD, IGHA, and IGHG genes in the GSE163650 dataset, we were unable to validate our findings for B cells and PCs. Lastly, the study included four BA cases with varying degrees of fibrosis. To reduce bias, we performed a partial merge, which may have limited our ability to precisely delineate the progression of fibrosis.

Conclusions

This study offers a comprehensive overview of the cellular composition at different stages of fibrosis and identifies cell types that may contribute to fibrosis in BA. These findings further elucidate the microenvironmental changes associated with the progression of BA fibrosis. The interaction between SAMs and BECs may promote EMT activation, highlighting a potential therapeutic strategy for BA treatment. Additionally, the high expression of CD96, EVL, S100A6, and S100A11 in fibrotic regions suggests their potential use as diagnostic and prognostic markers for BA.

Data availability

The data used and analyzed during the current study are available from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

References

Hartley, J. L., Davenport, M. & Kelly, D. A. Biliary atresia. Lancet 374, 1704–1713 (2009).

Lendahl, U., Lui, V. C. H., Chung, P. H. Y. & Tam, P. K. H. Biliary atresia—emerging diagnostic and therapy opportunities. EBioMedicine 74, 103689 (2021).

Shen, W. J., Chen, G., Wang, M. & Zheng, S. Liver fibrosis in biliary atresia. World J. Pediatr. 15, 117–123 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Liver immune profiling reveals pathogenesis and therapeutics for biliary atresia. Cell 183, 1867–1883.e1826 (2020).

Ye, C. et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal the fibrosis-related immune landscape of biliary atresia. Clin. Transl. Med. 12, e1070 (2022).

He, L. et al. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and post-Kasai portoenterostomy prognosis of biliary atresia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 11, 11692 (2021).

Schreiber, R. A., Harpavat, S., Hulscher, J. B. F. & Wildhaber, B. E. Biliary atresia in 2021: epidemiology, screening and public policy. J. Clin. Med. 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11040999 (2022).

Nomden, M., Beljaars, L., Verkade, H. J., Hulscher, J. B. F. & Olinga, P. Current concepts of biliary atresia and matrix metalloproteinase-7: a review of literature. Front. Med. 7, 617261 (2020).

Kong, F. et al. Progress in biomarkers related to biliary atresia. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 12, 305–315 (2024).

Moyer, K. et al. Staging of biliary atresia at diagnosis by molecular profiling of the liver. Genome Med. 2, 33 (2010).

Bessho, K. et al. Gene expression signature for biliary atresia and a role for interleukin-8 in pathogenesis of experimental disease. Hepatology 60, 211–223 (2014).

Luo, Z., Shivakumar, P., Mourya, R., Gutta, S. & Bezerra, J. A. Gene expression signatures associated with survival times of pediatric patients with biliary atresia identify potential therapeutic agents. Gastroenterology 157, 1138–1152.e1114 (2019).

So, J. et al. Biliary-atresia-associated mannosidase-1-alpha-2 gene regulates biliary and ciliary morphogenesis and laterality. Front. Physiol. 11, 538701 (2020).

Taylor, S. A. et al. Transcriptional profiling of pediatric cholestatic livers identifies three distinct macrophage populations. PLoS ONE 16, e0244743 (2021).

Xiao, M. H. et al. Integrative single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses identify a pathogenic cholangiocyte niche and TNFRSF12A as therapeutic target for biliary atresia. Hepatology, https://doi.org/10.1097/hep.0000000000001064 (2024).

Hafemeister, C. & Satija, R. Normalization and variance stabilization of single-cell RNA-seq data using regularized negative binomial regression. Genome Biol. 20, 296 (2019).

McGinnis, C. S., Murrow, L. M. & Gartner, Z. J. DoubletFinder: doublet detection in single-cell RNA sequencing data using artificial nearest neighbors. Cell Syst. 8, 329–337.e324 (2019).

Butler, A., Hoffman, P., Smibert, P., Papalexi, E. & Satija, R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 411–420 (2018).

Becht, E. et al. Dimensionality reduction for visualizing single-cell data using UMAP. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4314 (2018).

Ghosh, D. Incorporating the empirical null hypothesis into the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 11, https://doi.org/10.1515/1544-6115.1735 (2012).

Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14, 7 (2013).

Tirosh, I. et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 352, 189–196 (2016).

Chen, W. et al. Matrisome gene-based subclassification of patients with liver fibrosis identifies clinical and molecular heterogeneities. Hepatology 78, 1118–1132 (2023).

Guillot, A. & Tacke, F. Liver macrophages: old dogmas and new insights. Hepatol. Commun. 3, 730–743 (2019).

Qiu, X. et al. Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nat. Methods 14, 979–982 (2017).

Jin, S. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 12, 1088 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. Traditional Chinese medicine for bradyarrhythmia: evidence and potential mechanisms. Front. Pharm. 9, 324 (2018).

Sun, S., Zhu, J. & Zhou, X. Statistical analysis of spatial expression patterns for spatially resolved transcriptomic studies. Nat. Methods 17, 193–200 (2020).

Livingston, M. J. et al. Autophagy activates EGR1 via MAPK/ERK to induce FGF2 in renal tubular cells for fibroblast activation and fibrosis during maladaptive kidney repair. Autophagy 20, 1032–1053 (2024).

Ko, T. et al. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate the development of heart failure via Htra3-TGF-β-IGFBP7 axis. Nat. Commun. 13, 3275 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq of heart reveals intercellular communication drivers of myocardial fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Elife 12, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.80479 (2023).

Li, W. & Cheng, B. Knockdown of LncRNA NEAT1 inhibits myofibroblast activity in oral submucous fibrosis through miR-760/TPM1 axis. J. Dent. Sci. 17, 707–717 (2022).

Ramachandran, P. et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature 575, 512–518 (2019).

Zhang, M., Srivastava, G. & Lu, L. The pre-B cell receptor and its function during B cell development. Cell Mol. Immunol. 1, 89–94 (2004).

Wang, Q., Wang, F., Li, X., Ma, Z. & Jiang, D. Quercetin inhibits the amphiregulin/EGFR signaling-mediated renal tubular epithelial-mesenchymal transition and renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Phytother. Res. 37, 111–123 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. LINC01133 promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma epithelial-mesenchymal transition mediated by SPP1 through binding to Arp3. Cell Death Dis. 15, 492 (2024).

Ji, J. et al. Increased expression of OPN contributes to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and indicates a poor prognosis. J. Transl. Med. 21, 640 (2023).

Fu, M. et al. Down-regulation of STAT3 enhanced chemokine expression and neutrophil recruitment in biliary atresia. Clin. Sci. 135, 865–884 (2021).

Harada, K., Sato, Y., Isse, K., Ikeda, H. & Nakanuma, Y. Induction of innate immune response and absence of subsequent tolerance to dsRNA in biliary epithelial cells relate to the pathogenesis of biliary atresia. Liver Int. 28, 614–621 (2008).

Harada, K. et al. Innate immune response to double-stranded RNA in biliary epithelial cells is associated with the pathogenesis of biliary atresia. Hepatology 46, 1146–1154 (2007).

Lim, Y. Z. et al. Pkd1l1-deficiency drives biliary atresia through ciliary dysfunction in biliary epithelial cells. J. Hepatol. 81, 62–75 (2024).

Glessner, J. T. et al. Biliary atresia is associated with polygenic susceptibility in ciliogenesis and planar polarity effector genes. J. Hepatol. 79, 1385–1395 (2023).

Omenetti, A. et al. Hedgehog activity, epithelial-mesenchymal transitions, and biliary dysmorphogenesis in biliary atresia. Hepatology 53, 1246–1258 (2011).

Zheng, Q. et al. Potential therapeutic target of EGF on bile duct ligation model and biliary atresia children. Pediatr. Res. 94, 1297–1307 (2023).

Rayego-Mateos, S. et al. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and its ligands in kidney inflammation and damage. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 8739473 (2018).

Frank, J. W., Seo, H., Burghardt, R. C., Bayless, K. J. & Johnson, G. A. ITGAV (alpha v integrins) bind SPP1 (osteopontin) to support trophoblast cell adhesion. Reproduction 153, 695–706 (2017).

Erikson, D. W., Burghardt, R. C., Bayless, K. J. & Johnson, G. A. Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1, osteopontin) binds to integrin alpha v beta 6 on porcine trophectoderm cells and integrin alpha v beta 3 on uterine luminal epithelial cells, and promotes trophectoderm cell adhesion and migration. Biol. Reprod. 81, 814–825 (2009).

Yi, X. et al. SPP1 facilitates cell migration and invasion by targeting COL11A1 in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 22, 324 (2022).

Xu, C. et al. SPP1, analyzed by bioinformatics methods, promotes the metastasis in colorectal cancer by activating EMT pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 91, 1167–1177 (2017).

Li, M., Yuan, Z. & Tang, Z. Areca nut-induced AREG promote oral epithelial cell proliferation, migration, and EMT. Oral Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.15065 (2024).

Schinke, H. et al. A transcriptomic map of EGFR-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition identifies prognostic and therapeutic targets for head and neck cancer. Mol. Cancer 21, 178 (2022).

Tian, X. et al. Conditional depletion of macrophages ameliorates cholestatic liver injury and fibrosis via lncRNA-H19. Cell Death Dis. 12, 646 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Th2 signals induce epithelial injury in mice and are compatible with the biliary atresia phenotype. J. Clin. Investig. 121, 4244–4256 (2011).

Fabre, T. et al. Identification of a broadly fibrogenic macrophage subset induced by type 3 inflammation. Sci. Immunol. 8, eadd8945 (2023).

Lages, C. S., Simmons, J., Chougnet, C. A. & Miethke, A. G. Regulatory T cells control the CD8 adaptive immune response at the time of ductal obstruction in experimental biliary atresia. Hepatology 56, 219–227 (2012).

Brindley, S. M. et al. Cytomegalovirus-specific T-cell reactivity in biliary atresia at the time of diagnosis is associated with deficits in regulatory T cells. Hepatology 55, 1130–1138 (2012).

Taylor, A. E. et al. Interleukin 2 promotes hepatic regulatory T cell responses and protects from biliary fibrosis in murine sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology 68, 1905–1921 (2018).

Georgiev, H., Ravens, I., Papadogianni, G. & Bernhardt, G. Coming of age: CD96 emerges as modulator of immune responses. Front. Immunol. 9, 1072 (2018).

Blake, S. J., Dougall, W. C., Miles, J. J., Teng, M. W. & Smyth, M. J. Molecular pathways: targeting CD96 and TIGIT for cancer immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 5183–5188 (2016).

Feng, S., Isayev, O., Werner, J. & Bazhin, A. V. CD96 as a Potential immune regulator in cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021303 (2023).

Gong, J. et al. Establishment of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay system for determining soluble CD96 and its application in the measurement of sCD96 in patients with viral hepatitis B and hepatic cirrhosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 155, 207–215 (2009).

Damiano-Guercio, J. et al. Loss of Ena/VASP interferes with lamellipodium architecture, motility and integrin-dependent adhesion. Elife 9, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.55351 (2020).

Donhauser, N. et al. Transfer of HTLV-1 p8 and Gag to target T-cells depends on VASP, a novel interaction partner of p8. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008879 (2020).

Xia, P. et al. Therapeutic effects of recombinant human S100A6 and soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products(sRAGE) on CCl(4)-induced liver fibrosis in mice. Eur. J. Pharm. 833, 86–93 (2018).

Krenkel, O., Hundertmark, J., Ritz, T. P., Weiskirchen, R. & Tacke, F. Single cell RNA sequencing identifies subsets of hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts in liver fibrosis. Cells 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8050503 (2019).

Dong, X. H. et al. S100 calcium binding protein A6 and associated long noncoding ribonucleic acids as biomarkers in the diagnosis and staging of primary biliary cholangitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 27, 1973–1992 (2021).

Sobolewski, C. et al. S100A11/ANXA2 belongs to a tumour suppressor/oncogene network deregulated early with steatosis and involved in inflammation and hepatocellular carcinoma development. Gut 69, 1841–1854 (2020).

Zhu, T. et al. The S100 calcium binding protein A11 promotes liver fibrogenesis by targeting TGF-β signaling. J. Genet Genom. 49, 338–349 (2022).

Landi, C. et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage proteomic analysis in pulmonary fibrosis associated with systemic sclerosis: S100A6 and 14-3-3ε as potential biomarkers. Rheumatology 58, 165–178 (2019).

Lin, C. H. et al. S100A6 participates in initiation of autoimmune encephalitis and is under epigenetic control. Brain Behav. 13, e2897 (2023).

Yang, F. et al. S100A6 Regulates nucleus pulposus cell apoptosis via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway: an in vitro and in vivo study. Mol. Med. 30, 87 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. S100A11 regulates nasal epithelial cell remodeling and inflammation in CRSwNPs via the RAGE-mediated AMPK-STAT3 pathway. Mol. Immunol. 140, 35–46 (2021).

Navrátilová, A. et al. S100A11 (calgizzarin) is released via NETosis in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and stimulates IL-6 and TNF secretion by neutrophils. Sci. Rep. 11, 6063 (2021).

Bin, L. et al. Inhibition of S100A11 gene expression impairs keratinocyte response against vaccinia virus through downregulation of the IL-10 receptor 2 chain. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 124, 270–277.e271 (2009).

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Tianshan Talent Training Program (Grant No. 2023TSYCJC0052), Tianjin Municipal Science& Technology Planning Project (Grant No. 21ZXGWSY00070), and Tianjin Applied Basic Research Project Planning Project (Grant No. 22JCZDJC00290).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. and T.F.L. designed the study and analyzed the data. T.F.L., S.W.L., L.G., S.J.Z., and Y.Q.C. collected the data. T.F.L., Q.H.Y., Y.M., J.Y.L., and J.M. drafted and revised the manuscript. T.F.L., Y.L.Z., and A.A. revised the images. T.F.L. and J.H.Z. revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent for publication

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Children’s Hospital (2022-SYYJCYJ-008) and informed consent was obtained from the legal guardian of each patient.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Li, T., Liu, S. et al. Scar-associated macrophages and biliary epithelial cells interaction exacerbates hepatic fibrosis in biliary atresia. Pediatr Res 99, 362–374 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04100-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04100-2