Abstract

Study design

Cross-sectional study.

Objectives

To identify socio-demographic and injury-related factors that contribute to activity limitations and participation restrictions in people with spinal cord injury (SCI) in Bangladesh.

Setting

Centre for the Rehabilitation of the Paralysed (CRP), Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Methods

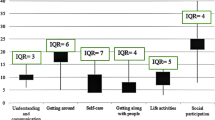

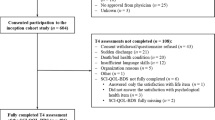

This study involved 120 (83% men) participants with SCI; their median (interquartile range) age and injury duration were 34 (25–43) years and 5 (2–10) years, respectively. Data were collected from the follow-up records kept by the Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) unit of CRP and a subsequent home visit that included interview-administered questions, questionnaires, and a neurological examination. The dependent variables were activity limitations and participation restrictions, assessed with the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0, scored 0–100; a high score indicates greater activity limitations and participation restrictions). Independent variables included socio-demographic factors (i.e., age, sex, marital status, educational level, monthly household income, employment status, and place of residence) and injury-related factors (i.e., injury duration, cause of injury, injury severity, and type of paralysis). Multivariable linear regression analyses were performed to identify the factors that independently contributed to activity limitations and participation restrictions.

Results

Three significant independent variables explained 20.7% of the variance in activity limitations and participation restrictions (WHODAS 2.0 score), in which tetraplegia was the strongest significant contributing factor, followed by rural residence and complete injury.

Conclusions

This study would indicate that tetraplegia, complete injury, and residing in a rural area are the major contributions in limiting the activity and participation following SCI in Bangladesh.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Kirchberger I, Biering-Sorensen F, Charlifue S, Baumberger M, Campbell R, Kovindha A, et al. Identification of the most common problems in functioning of individuals with spinal cord injury using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:221–9.

Kemp B, Adkins R, Thompson L. Aging with a spinal cord injury: what recent research shows. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2004;10:175–197.

Thompson L, Yakura J. Aging Related Functional Changes in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2001;6:69–82.

Barclay L, McDonald R, Lentin P. Social and community participation following spinal cord injury: a critical review. Int J Rehabil Res. 2015;38:1–19.

World Health Organization. International perspectives on spinal cord injury; 2013.

Hossain MS, Rahman MA, Bowden JL, Quadir MM, Herbert RD, Harvey LA. Psychological and socioeconomic status, complications and quality of life in people with spinal cord injuries after discharge from hospital in Bangladesh: a cohort study. Spinal Cord. 2015;54:483–9.

Hossain MS, Rahman MA, Herbert RD, Quadir MM, Bowden JL, Harvey LA. Two-year survival following discharge from hospital after spinal cord injury in Bangladesh. Spinal Cord. 2015;54:132–6.

Whiteneck G, Meade MA, Dijkers M, Tate DG, Bushnik T, Forchheimer MB. Environmental factors and their role in participation and life satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1793–803.

Whiteneck G, Tate D, Charlifue S. Predicting community reintegration after spinal cord injury from demographic and injury characteristics. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1485–91.

Krause JS, Broderick L. Outcomes after spinal cord injury: comparisons as a function of gender and race and ethnicity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:355–62.

Jorgensen S, Iwarsson S, Lexell J. Secondary health conditions, activity limitations, and life satisfaction in older adults with long-term spinal cord injury. PM & R. 2016;9:356–66.

Hoque MF, Grangeon C, Reed K. Spinal cord lesions in Bangladesh: an epidemiological study 1994-1995. Spinal Cord. 1999;37:858–61.

Islam MS, Hafez MA, Akter M. Characterization of spinal cord lesion in patients attending a specialized rehabilitation center in Bangladesh. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:783–6.

Centre for the Rehabilitation of the Paralyzed. Annual report: 2014–2015, celebrating 36 years of service. Bangladesh: CRP Printing Press; 2015.

Ustun T, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J. Measuring health and disability: manual for WHO disability assessment schedule (WHODAS 2.0). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A, et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:535–46.

Wolf AC, Tate RL, Lannin NA, Middleton J, Lane-Brown A, Cameron ID. The World health organization disability assessment scale, WHODAS II: reliability and validity in the measurement of activity and participation in a spinal cord injury population. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44:747–55.

Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Rehm J, Kennedy C, Epping-Jordan J, et al. Developing the World Health Organization disability assessment schedule 2.0. BullWorld Health Organ. 2010;88:815–23.

Federici S, Bracalenti M, Meloni F, Luciano JV. World Health Organization disability assessment schedule 2.0: an international systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2016;39:2347–80.

Fitch T, Villanueva G, Quadir MM, Sagiraju HK, Alamgir H. The prevalence and risk factors of post-traumatic stress disorder among workers injured in rana plaza building collapse in Bangladesh. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58:756–63.

Population Housing Census. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. 2011. http://203.112.218.65/WebTestApplication/userfiles/Image/National%20Reports/PopulationHousingCensus2011.pdf. Accessed 16 Feb 2017.

Kirshblum S, William W. Updates for the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25:505–17.

Schuld C, Wiese J, Franz S, Putz C, Stierle I, Smoor I, et al. Effect of formal training in scaling, scoring and classification of the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:282–88.

Walden K, Belanger LM, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns SP, Echeverria E, Kirshblum S, et al. Development and validation of a computerized algorithm for international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (ISNCSCI). Spinal Cord. 2016;54:197–03.

Rick Hansen Institute. ISNCSCI algorithm. http://www.isncscialgorithm.com/. Accessed 22 June 2017.

Katz MH. Multivariable analysis: a practical guide for clinicians and public health researchers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

Skold C, Levi R, Seiger A. Spasticity after traumatic spinal cord injury: nature, severity, and location. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1548–57.

Ravensbergen HJ, de Groot S, Post MW, Slootman HJ, van der Woude LH, Claydon VE. Cardiovascular function after spinal cord injury: prevalence and progression of dysfunction during inpatient rehabilitation and 5 years following discharge. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014;28:219–29.

Jackson AB, Groomes TE. Incidence of respiratory complications following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:270–5.

Harvey LA, Batty J, Jones R, Crosbie J. Hand function of C6 and C7 tetraplegics 1-16 years following injury. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:37–43.

Sekaran P, Vijayakumari F, Hariharan R, Zachariah K, Joseph SE, Kumar RK. Community reintegration of spinal cord-injured patients in rural south India. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:628–32.

Fisher RJ. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J Consumer Res. 1993;20:303–315.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants for their cooperation, and the physiotherapists Rasel Howlader and Maisha Hoque for data collection. We gratefully acknowledge Kazi Imdadul Hoque, a clinical physiotherapist, CRP for his valuable suggestions to the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kader, M., Perera, N.K.P., Sohrab Hossain, M. et al. Socio-demographic and injury-related factors contributing to activity limitations and participation restrictions in people with spinal cord injury in Bangladesh. Spinal Cord 56, 239–246 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0001-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0001-y

This article is cited by

-

Disability trajectories individuals with spinal cord injury in mainland China: do psychosocial resources and diseases factors predict trajectories?

Spinal Cord (2025)

-

Meaning of Work Participation After Spinal Cord Injury in Bangladesh: A Qualitative Study in a Low- and Middle-Income Country Context

Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation (2024)

-

An assessment of disability and quality of life in people with spinal cord injury upon discharge from a Bangladesh rehabilitation unit

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Loss of work-related income impoverishes people with SCI and their families in Bangladesh

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Health status, quality of life and socioeconomic situation of people with spinal cord injuries six years after discharge from a hospital in Bangladesh

Spinal Cord (2019)