Abstract

Study design

Prospective cohort study.

Objectives

To evaluate the relationship between quality of life (QOL) after a traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI) and acute predictors, with a particular emphasis on the initial severity of the neurological injury. Secondarily, to compare the QOL after a TSCI with the general population.

Setting

A single Level-1 SCI-trauma centre.

Methods

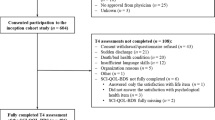

A cohort of 119 individuals admitted after a cervical TSCI between April 2010 and September 2016 was studied. QOL was assessed using the SF-36v2 questionnaire 6–12 months following the injury, and compared to the general population. The relationship between the initial severity of the neurological injury and the SF-36 summary scores was assessed using linear multivariable regression analyses.

Results

Individuals sustaining less severe neurological injury (grade D) exhibited higher PCS than individuals with grades A, B or C injury. Individuals with initial grade A injury showed increased MCS than individuals with incomplete grade B, C or D injury, with 42.9% scoring higher than the general population. The initial grade was significantly associated with chronic PCS and MCS.

Conclusions

The initial severity of the neurological injury after a cervical TSCI may be used to estimate QOL in the subacute period following the injury. Individuals with complete tetraplegia may report good mental QOL despite severe physical impairment. Our findings could help clinicians to determine realistic expectations for patients in terms of QOL, and optimize the rehabilitation plan based on the initial evaluation after a TSCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Sezer N, Akkus S, Ugurlu FG. Chronic complications of spinal cord injury. World J Orthop. 2015;6:24–33.

Richard-Denis A, Feldman D, Thompson C, Mac-Thiong JM. Prediction of functional recovery six months following traumatic spinal cord injury during acute care hospitalization. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;41:1–9.

Consortium for Spinal Cord M. Early acute management in adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31:403–79.

Kirshblum SC, O’Connor KC. Predicting neurologic recovery in traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:1456–66.

van Middendorp JJ, Hosman AJ, Donders AR, Pouw MH, Ditunno JF Jr, Curt A, et al. A clinical prediction rule for ambulation outcomes after traumatic spinal cord injury: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377:1004–10.

Organization WH Health statistics and information systems. WHOQOL: measuring Quality of life: WHO; 2018. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/. Accessed 15 Apr 2018.

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:71–5.

Veenhoven R. Social conditions for human happiness: a review of research. Int J Psychol. 2015;50:379–91.

Wilson JR, Grossman RG, Frankowski RF, Kiss A, Davis AM, Kulkarni AV, et al. A clinical prediction model for long-term functional outcome after traumatic spinal cord injury based on acute clinical and imaging factors. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:2263–71.

Dijkers M. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: a meta analysis of the effects of disablement components. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:829–40.

Cushman DM, Thomas K, Mukherjee D, Johnson R, Spill G. Perceived quality of life with spinal cord injury: a comparison between emergency medicine and physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians. PM R. 2015;7:962–9.

Lidal IB, Veenstra M, Hjeltnes N, Biering-Sorensen F. Health-related quality of life in persons with long-standing spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:710–5.

Forchheimer M, McAweeney M, Tate DG. Use of the SF-36 among persons with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83:390–5.

Kivisild A, Sabre L, Tomberg T, Ruus T, Korv J, Asser T, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury in Estonia. Spinal Cord. 2014;52:570–5.

Quebec Gd. Quebec handy numbers. In: Quebec Idlsd, editor. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Quebec ed: Institut de la statistique du Quebec; 2017.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A, et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:535–46.

Baker SP, O’Neill B. The injury severity score: an update. J Trauma. 1976;16:882–5.

Charlson M, Wells MT, Ullman R, King F, Shmukler C. The Charlson comorbidity index can be used prospectively to identify patients who will incur high future costs. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112479.

Chappell PWS. Quality of life following spinal cord injury for 20-40 Year old males living in Sri Lanka. Asia Pac Disabil Rehabil J. 2003;14:168–78.

Post M, Noreau L. Quality of life after spinal cord injury. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2005;29:139–46.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83.

RA A. When to use the Benferroni correction. Ophtalmic Physiol Opt. 2014;34:502–08.

Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ. 1998;316:1236–8.

Hopman WM, Towheed T, Anastassiades T, Tenenhouse A, Poliquin S, Berger C, et al. Canadian normative data for the SF-36 health survey. Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study Research Group. CMAJ. 2000;163:265–71.

Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD, Coleman WP, Tuszynski MH, Lammertse D, et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:190–205.

Noreau L, Fougeyrollas P, Post M, Asano M. Participation after spinal cord injury: the evolution of conceptualization and measurement. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2005;29:147–56.

Erosa NA, Berry JW, Elliott TR, Underhill AT, Fine PR. Predicting quality of life 5 years after medical discharge for traumatic spinal cord injury. Br J Health Psychol. 2014;19:688–700.

Haran MJ, Lee BB, King MT, Marial O, Stockler MR. Health status rated with the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:2290–5.

Abrantes-Pais Fde N, Friedman JK, Lovallo WR, Ross ED. Psychological or physiological: why are tetraplegic patients content? Neurology. 2007;69:261–7.

Farivar SS, Cunningham WE, Hays RD. Correlated physical and mental health summary scores for the SF-36 and SF-12 Health Survey, V.I. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:54.

Taft C, Karlsson J, Sullivan M. Do SF-36 summary component scores accurately summarize subscale scores? Qual life Res. 2001;10:395–404.

Bonanno GA, Kennedy P, Galatzer-Levy IR, Lude P, Elfstrom ML. Trajectories of resilience, depression, and anxiety following spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2012;57:236–47.

Albrecht GL, Devlieger PJ. The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:977–88.

Diener ESE. Measuring quality of life: economic, social, and subjective indicators. Soc Indic Res. 1997;40:189–216.

Clayton KS, Chubon RA. Factors associated with the quality of life of long-term spinal cord injured persons. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:633–8.

Ames H, Wilson C, Barnett SD, Njoh E, Ottomanelli L. Does functional motor incomplete (AIS D) spinal cord injury confer unanticipated challenges? Rehabil Psychol. 2017;62:401–6.

Martz E, Livneh H, Priebe M, Wuermser LA, Ottomanelli L. Predictors of psychosocial adaptation among people with spinal cord injury or disorder. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1182–92.

Westgren N, Levi R. Quality of life and traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:1433–9.

Ebrahimzadeh MH, Soltani-Moghaddas SH, Birjandinejad A, Omidi-Kashani F, Bozorgnia S. Quality of life among veterans with chronic spinal cord injury and related variables. Arch Trauma Res. 2014;3:e17917.

Mortenson WB, Noreau L, Miller WC. The relationship between and predictors of quality of life after spinal cord injury at 3 and 15 months after discharge. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:73–9.

Author contributions

ARD contributed to the design of the study, data collection, statistical analysis, data interpretation and article redaction. CT contributed to the data collection and statistical analysis. JMMT contributed to the design of the study, data interpretation and article preparation.

Funding

This research was funded by the US Department of Defense Spinal Cord Injury Research Program. Part of the data was collected through the Rick Hansen Spinal Cord Injury Registry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richard-Denis, A., Thompson, C. & Mac-Thiong, JM. Quality of life in the subacute period following a cervical traumatic spinal cord injury based on the initial severity of the injury: a prospective cohort study. Spinal Cord 56, 1042–1050 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0178-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0178-8

This article is cited by

-

A Systematic Review of the Impact of Spinal Cord Injury on Costs and Health-Related Quality of Life

PharmacoEconomics - Open (2024)

-

The EQ-5D-5L in patients admitted to a hospital in Japan with recent spinal cord injury: a descriptive study

Spinal Cord (2019)

-

The relevance of MRI for predicting neurological recovery following cervical traumatic spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2019)