Abstract

Study design

Three-round Delphi study followed by a Consensus Conference with selected stakeholders.

Objectives

To identify a set of core educational content that people with spinal cord injury (SCI) need to acquire during rehabilitation.

Setting

The Delphi study was performed electronically. The Consensus Conference was held at the Città della Salute e della Scienza University Hospital of Turin, Italy.

Methods

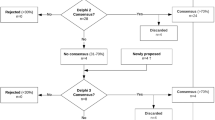

A panel of 20 experts (healthcare professionals and SCI survivors) participated in a three-round Delphi study. In round 1, arguments for core educational content were solicited and reduced into items. In rounds 2 and 3, a five-point Likert scale was used to find consensus on and validate core educational content items (threshold for consensus and agreement: 60% and 80%, respectively). A Consensus Conference involving 32 stakeholders was held to discuss, modify (if appropriate) and approve the list of validated items.

Results

The 171 arguments proposed in round 1 were reduced into 74 items; 67 were validated in round 3. The Consensus Conference approved a final list of 72 core educational content items, covering 16 categories, which were made into a checklist.

Conclusions

Consensus was achieved for a set of core educational content for people with SCI. The resultant checklist could serve as an assessment tool for both healthcare professionals and SCI survivors. It can also be used to support SCI survivors’ education, streamline resource use and bridge the gap between information provided during rehabilitation and information SCI survivors need to function in the community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Matter B, Feinberg M, Schomer K, Harniss M, Brown P, Johnson K. Information needs of people with spinal cord injuries. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:545–54.

Manns PJ, May LA. Perceptions of issues associated with the maintenance and improvement of long-term health in people with SCI. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:411–9.

Pollard C, Kennedy P. A longitudinal analysis of emotional impact, coping strategies and post-traumatic psychological growth following spinal cord injury: a 10-year review. Br J Health Psychol. 2007;12:347–62.

Conti A, Dimonte V, Rizzi A, Clari M, Mozzone S, Garrino L, et al. Barriers and facilitators of education provided during rehabilitation of people with spinal cord injuries: a qualitative description. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0240600.

Conti A, Clari M, Kangasniemi M, Martin B, Borraccino A, Campagna S. What self-care behaviours are essential for people with spinal cord injury? A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Disabil Rehabilitation. 2020;0:1–16.

Rivers CS, Fallah N, Noonan VK, Whitehurst DG, Schwartz CE, Finkelstein JA, et al. Health conditions: effect on function, health-related quality of life, and life satisfaction after traumatic spinal cord injury. A prospective observational registry cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabilitation. 2018;99:443–51.

Todorovic M, Barton M, Bentley S, St John JA, Ekberg J. Designing accessible educational resources for people living with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2020:1–13. [Epub ahead of print].

May L, Day R, Warren S. Evaluation of patient education in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: knowledge, problem-solving and perceived importance. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:405–13.

Robineau S, Nicolas B, Mathieu L, Duruflé A, Leblong E, Fraudet B, et al. Assessing the impact of a patient education programme on pressure ulcer prevention in patients with spinal cord injuries. J Tissue Viability. 2019;28:167–72.

Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Martin Ginis KA, Latimer-Cheung AE, Bourne C, Campbell D, Cappe S, et al. Development of an evidence-informed leisure time physical activity resource for adults with spinal cord injury: the SCI Get Fit Toolkit. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:491–500.

Shepherd JD, Badger-Brown KM, Legassic MS, Walia S, Wolfe DL. SCI-U: e-learning for patient education in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;35:319–29.

Whalley Hammell K. Experience of rehabilitation following spinal cord injury: a meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:260–74.

van Wyk K, Backwell A, Townson A. A narrative literature review to direct spinal cord injury patient education programming. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2015;21:49–60.

Evardone M, Wilson CS, Weinel D, Soble JR, Kang Y. Does attendance in SCI education courses impact health outcomes in acute rehabilitation? J Spinal Cord Med. 2018;41:17–27.

Fann JR, Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Tate DG, Wilson CS, Temkin N, et al. Depression after spinal cord injury: comorbidities, mental health service use, and adequacy of treatment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:352–60.

Portmann Bergamaschi R, Escorpizo R, Staubli S, Finger ME. Content validity of the work rehabilitation questionnaire-self-report version WORQ-SELF in a subgroup of spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord. 2014;52:225–30.

Hoffman JM, Bombardier CH, Graves DE, Kalpakjian CZ, Krause JS. A longitudinal study of depression from 1 to 5 years after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:411–8.

Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–15.

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53:205–12.

Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manag. 2004;42:15–29.

Hsu C-C, Sanford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Evaluation. 2007;12:1–8.

Ludwig B. Predicting the future: have you considered using the Delphi methodology? J Ext. 1997;35. https://www.joe.org/joe/1997october/tt2.php. Accessed 9 Mar 2020.

Khodyakov D, Grant S, Denger B, Kinnett K, Martin A, Peay H, et al. Practical considerations in using online modified-Delphi approaches to engage patients and other stakeholders in clinical practice guideline. Dev Patient. 2020;13:11–21.

Green B, Jones M, Hughes D, Williams A. Applying the Delphi technique in a study of GPs’ information requirements. Health Soc Care Community. 1999;7:198–205.

Tastle WJ, Abdullat A, Wierman MJ. A new approach in requirements elicitation analysis. J Emerg Technol Web Intell. 2010;2:221–31.

Tastle WJ, Wierman MJ. Consensus and dissention: a measure of ordinal dispersion. Int J Approx Reasoning. 2007;45:531–45.

Meijering JV, Kampen JK, Tobi H. Quantifying the development of agreement among experts in Delphi studies. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2013;80:1607–14.

DeJong G, Tian W, Hsieh C-H, Junn C, Karam C, Ballard PH, et al. Rehospitalization in the first year of traumatic spinal cord injury after discharge from medical rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:S87–97.

Jensen MP, Truitt AR, Schomer KG, Yorkston KM, Baylor C, Molton IR. Frequency and age effects of secondary health conditions in individuals with spinal cord injury: a scoping review. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:882–92.

Jörgensen S, Iwarsson S, Lexell J. Secondary health conditions, activity limitations, and life satisfaction in older adults with long-term spinal cord. Inj PM R. 2017;9:356–66.

Alexander MS, Aisen CM, Alexander SM, Aisen ML. Sexual concerns after Spinal Cord Injury: an update on management. NeuroRehabilitation. 2017;41:343–57.

Adriaansen JJE, Asbeck FWA, Lindeman E, Woude LHVv, Groot S, Post MWM. Secondary health conditions in persons with a spinal cord injury for at least 10 years: design of a comprehensive long-term cross-sectional study. Disabil Rehabilitation. 2013;35:1104–10.

Müller R, Landmann G, Béchir M, Hinrichs T, Arnet U, Jordan X, et al. Chronic pain, depression and quality of life in individuals with spinal cord injury: mediating role of participation. J Rehabil Med. 2017;49:489–96.

Gabbe BJ, Nunn A. Profile and costs of secondary conditions resulting in emergency department presentations and readmission to hospital following traumatic spinal cord injury. Injury. 2016;47:1847–55.

Ullah MM, Fossey E, Stuckey R. The meaning of work after spinal cord injury: a scoping review. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:92–105.

Post MWM, van Leeuwen CMC. Psychosocial issues in spinal cord injury: a review. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:382–9.

Conti A, Clari M, Arese S, Bandini B, Cavallaro L, Mozzone S, et al. Validation and psychometric evaluation of the Italian version of the Spinal Cord Injury Secondary Conditions Scale. Spinal Cord. 2020;58:496–503.

New PW. Secondary conditions in a community sample of people with spinal cord damage. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39:665–70.

Burkell JA, Wolfe DL, Potter PJ, Jutai JW. Information needs and information sources of individuals living with spinal cord injury. Health Inf Libraries J. 2006;23:257–65.

Kirby RL, Mitchell D, Sabharwal S, McCranie M, Nelson AL. Manual wheelchair skills training for community-dwelling veterans with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0168330.

Worobey L, Oyster M, Nemunaitis G, Cooper R, Boninger ML. Increases in wheelchair breakdowns, repairs, and adverse consequences for people with traumatic spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91:463–9.

Nelson AL, Groer S, Palacios P, Mitchell D, Sabharwal S, Kirby RL, et al. Wheelchair-related falls in veterans with spinal cord injury residing in the community: a prospective cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1166–73.

Gontkovsky ST, Russum P, Stokic DS. Perceived information needs of community-dwelling persons with chronic spinal cord injury: findings of a survey and impact of race. Disabil Rehabilitation. 2007;29:1305–12.

Chang F-H, Liu C-H, Hung H-P. An in-depth understanding of the impact of the environment on participation among people with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:2192–9.

Buscemi V, Cassidy E, Kilbride C, Reynolds FA. A qualitative exploration of living with chronic neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury: an Italian perspective. Disabil Rehabilitation. 2018;40:577–86.

Walker A, Selfe J. The Delphi method: a useful tool for the allied health researcher. Br J Ther Rehabilitation. 1996;3:677–81.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the participants from the SCI Regional Coordination of Torino, their caregivers and healthcare professionals of the Italian Spinal Cord Society (SIMS) for dedicating their time to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB, AC and AR were responsible for designing and writing the study protocol, and for submitting the study to the ethical committee. AB and AC were also responsible for writing the report and coordinating research activities. AR and SM were responsible for database management and analysed the data. AB, AR and SC interpreted the results. SC and VD provided methodological supervision to the study and feedback on the report.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved (Resolution No. 105785/2016 - #CS2/28) by the Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, Mauriziano Hospital, ASL TO 1 Research Ethics Committee. All applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed. All respondents to the three rounds of the Delphi study were included only after acknowledging their willingness to participate in the study. The participants in the Consensus Conference provided written, informed consent and anonymity was maintained throughout the research process.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Borraccino, A., Conti, A., Rizzi, A. et al. Developing a consensus on the core educational content to be acquired by people with spinal cord injuries during rehabilitation: findings from a Delphi study followed by a Consensus Conference. Spinal Cord 59, 1187–1199 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00652-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00652-2

This article is cited by

-

The technical expert/clinical user/patient panel (TECUPP): centering patient and family perspectives in patient-reported measure development

Research Involvement and Engagement (2025)