Abstract

Study design

Longitudinal cohort study of privately insured beneficiaries with and without traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI).

Objectives

Compare the incidence of and adjusted hazards for psychological morbidities among adults with and without traumatic SCI, and examine the effect of chronic centralized and neuropathic pain on outcomes.

Setting

Privately insured beneficiaries were included if they had an ICD-9-CM diagnostic code for traumatic SCI (n = 9081). Adults without SCI were also included (n = 1,474,232).

Methods

Incidence of common psychological morbidities were compared at 5-years of enrollment. Survival models were used to quantify unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for incident psychological morbidities.

Results

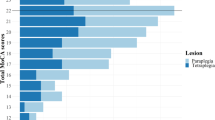

Adults with SCI had a higher incidence of any psychological morbidity (59.1% vs. 30.9%) as compared to adults without SCI, and differences were to a clinically meaningful extent. Survival models demonstrated that adults with SCI had a greater hazard for any psychological morbidity (HR: 1.67; 95%CI: 1.61, 1.74), and all but one psychological disorder (impulse control disorders), and ranged from HR: 1.31 (1.24, 1.39) for insomnia to HR: 2.10 (1.77, 2.49) for post-traumatic stress disorder. Centralized and neuropathic pain was associated with all psychological disorders, and ranged from HR: 1.31 (1.23, 1.39) for dementia to HR: 3.83 (3.10, 3.68) for anxiety.

Conclusions

Adults with SCI have a higher incidence of and risk for common psychological morbidities, as compared to adults without SCI. Efforts are needed to facilitate the development of early interventions to reduce risk of chronic centralized and neuropathic pain and psychological morbidity onset/progression in this higher risk population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

Data availability

All data accessed for this study were purchased through the ClinformaticsTM Data Mart Database, a de-identified nationwide claims database of all beneficiaries from a single private payer. Thus, data are not eligible or available for public data access.

References

National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, Facts and Figures at a Glance. Birmingham, AL: University of Alabama at Birmingham; 2021.

Gerhart K, Koziol-McLain J, Lowenstein S, GG W. Quality of life following spinal cord injury: knowledge and attitudes of emergency care providers. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:807–12.

Cushman LA, Dijkers MP. Depressed mood in spinal cord injured patients: staff perceptions and patient realities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:191–6.

Frank RG, Elliott TR, Corcoran JR, Wonderlich SA. Depression after spinal cord injury: is it necessary?☆. Clin Psychol Rev. 1987;7:611–30.

Williams R, Murray A. Prevalence of depression after spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:133–40.

Peterson MD, Kamdar N, Chiodo A, Tate DG. Psychological morbidity and chronic disease among adults with traumatic spinal cord injuries: a longitudinal cohort study of privately insured bene ficiaries. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:920–8.

Craig A, Tran Y, Middleton J. Psychological morbidity and spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:108–14.

Cragg JJ, Stone JA, Krassioukov AV. Management of cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with chronic spinal cord injury: an evidence-based review. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1999–2012.

Quinones AR, Markwardt S, Botoseneanu A. Multimorbidity combinations and disability in older adults. J Gerontol a-Biol. 2016;71:823–30.

Tolentino JC, Schmidt SL. Association between depression and cardiovascular disease: A review based on QT dispersion. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26:1568–70.

Krause JS, Kemp B, Coker J. Depression after spinal cord injury: relation to gender, ethnicity, aging, and socioeconomic indicators. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:1099–109.

Mahmoudi E, Lin P, Peterson MD, Meade MA, Tate DG, Kamdar N. Traumatic spinal cord injury and risk of early and late onset alzheimer’s disease and related dementia: large longitudinal study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:1147–54.

Huynh V, Rosner J, Curt A, Kollias S, Hubli M, Michels L. Disentangling the effects of spinal cord injury and related neuropathic pain on supraspinal neuroplasticity: a systematic review on neuroimaging. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1413.

Kennedy P, Sherlock O, Sandu N. Rehabilitation outcomes in people with pre-morbid mental health disorders following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:290–4.

McDonald SD, Mickens MN, Goldberg-Looney LD, Mutchler BJ, Ellwood MS, Castillo TA. Mental disorder prevalence among U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs outpatients with spinal cord injuries. The. J Spinal Cord Med. 2018;41:691–702.

Goldenberg DL, Clauw DJ, Palmer RE, Clair AG. Opioid use in fibromyalgia: a cautionary tale. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:640–8.

Peng X, Robinson RL, Mease P, Kroenke K, Williams DA, Chen Y, et al. Long-term evaluation of opioid treatment in fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:7–13.

Hairston DR, Gibbs TA, Wong SS, Jordan A. Clinician bias in diagnosis and treatment. In: Medlock MSD, Shtasel D, Trinh NH, Williams DR editors. Racism and psychiatry. Current clinical psychiatry. Cham Switzerland: Humana Press, Springer Nature; 2019.

Heinemann AW, Wilson CS, Huston T, Koval J, Gordon S, Gassaway J, et al. Relationship of psychology inpatient rehabilitation services and patient characteristics to outcomes following spinal cord injury: the SCIRehab project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;35:578–92.

Whiteneck GG, Gassaway J, Dijkers MP, Lammertse DP, Hammond F, Heinemann AW, et al. Inpatient and postdischarge rehabilitation services provided in the first year after spinal cord injury: findings from the SCIRehab Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:361–8.

Wilson C, Huston T, Koval J, Gordon SA, Schwebel A, Gassaway J. SCIRehab Project series: the psychology taxonomy. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:319–28.

Fann JR, Bombardier C, Richards JS, Tate DG, Wilson CS, Temkin N, et al. Depression after spinal cord injury: comorbidities, mental health service use, and adequacy of treatment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:352–60.

Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Krause JS, Tulsky D, Tate DG. Symptoms of major depression in people with spinal cord injury: implications for screening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1749–56.

Benson K, Hartz AJ. A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N. Engl J Med. 2000;342:1878–86.

Reeves S, Garcia E, Kleyn M, Housey M, Stottlemyer R, Lyon-Callo S, et al. Identifying sickle cell disease cases using administrative claims. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:S61–7. 5 Suppl

Kerr EA, McGlynn EA, Van Vorst KA, Wickstrom SL. Measuring antidepressant prescribing practice in a health care system using administrative data: implications for quality measurement and improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2000;26:203–16.

Leslie WD, Lix LM, Yogendran MS. Validation of a case definition for osteoporosis disease surveillance. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:37–46.

Doktorchik C, Patten S, Eastwood C, Peng M, Chen G, Beck CA, et al. Validation of a case definition for depression in administrative data against primary chart data as a reference standard. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:9.

Noyes K, Liu H, Lyness JM, Friedman B. Medicare beneficiaries with depression: comparing diagnoses in claims data with the results of screening. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:1159–66.

Acknowledgements

This research was developed in part under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR #90RTHF0001-01-00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP and EM were responsible for designing the conceptual framework of the study. PL and NK conducted the statistical analyses. MM, GR, and JK contributed substantially to the data interpretation and the article preparation. All authors provided writing support and contributed to the editing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics statement

This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the researchers’ institution.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peterson, M.D., Meade, M.A., Lin, P. et al. Psychological morbidity following spinal cord injury and among those without spinal cord injury: the impact of chronic centralized and neuropathic pain. Spinal Cord 60, 163–169 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00731-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00731-4

This article is cited by

-

The impact of non-invasive brain-computer interface technology on the therapeutic effect of patients with spinal cord injury: a summary of evidence based on meta-analysis

Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation (2025)

-

Incident traumatic spinal cord injury and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia: longitudinal case and control cohort study

Spinal Cord (2024)

-

A comprehensive look at the psychoneuroimmunoendocrinology of spinal cord injury and its progression: mechanisms and clinical opportunities

Military Medical Research (2023)

-

Neuropathic Pain and Spinal Cord Injury: Management, Phenotypes, and Biomarkers

Drugs (2023)