Abstract

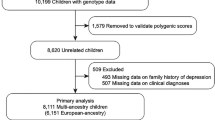

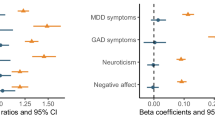

Lockdowns and social restrictions imposed in response to the Covid-19 pandemic intensified the proximity and reciprocal exposure among members of nuclear families. It is unclear how variation in mental distress during this period is attributed to potential influences of family members. This study used genetic data from adolescents (n = 4 388), mothers (n = 27 852) and fathers (n = 25 953), to disentangle the contributions of parent-driven, child-driven, and partner-driven components to mental distress during the first two months of the Covid-19 lockdown. Separate models also included adolescents’ non-pandemic mental distress as outcomes (n = 13 484). Trio genome-wide complex trait analyses separated two types of genetic components; direct–how an individual’s genotype is associated with their own mental distress, and indirect–how an individual’s genotype is associated with the mental distress of family members. A trio polygenic score (PGS) design was used to investigate associations of specific genetic liability factors with mental distress, and whether these changed over time (PGS×time). Results suggest that family-level genetic factors contribute to mental distress; variance components capturing indirect genetic effects accounted for 10% of adolescent mental distress (mother-driven), 2–3% of maternal (partner-driven), and 5% of paternal mental distress (child-driven). Mothers’ depression and ADHD PGS were positively associated with fathers’ mental distress. No PGS×time interactions were found. Direct genetic effects accounted for 9–10% variance in mental distress across family members, partly explained by genetic variants associated with anxiety, depression, ADHD and neuroticism. These findings highlight the importance of family dynamics and emphasize the potential value of including family members in mental health interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Code availability

Analysis code is publicly available on GitHub: https://github.com/psychgen/Family-trios-Covid19.

References

Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:1142–50.

Madigan S, Racine N, Vaillancourt T, Korczak DJ, Hewitt JM, Pador P, et al. Changes in depression and anxiety among children and adolescents from before to during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177:567–81.

Gorostiaga A, Aliri J, Balluerka N, Lameirinhas J. Parenting styles and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: A systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3192.

Gustavson K, Ystrom E, Stoltenberg C, Susser E, Surén P, Magnus P, et al. Smoking in pregnancy and child ADHD. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20162509.

Gustavson K, Ystrom E, Ask H, Ask Torvik F, Hornig M, Susser E, et al. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy and offspring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder–a longitudinal sibling control study. JCPP Adv. 2021;1:e12020.

Hegemann L, Eilertsen E, Pettersen JH, Corfield EC, Cheesman R, Frach L, et al. Direct and indirect genetic effects on early neurodevelopmental traits. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2025;66:1053-64.

Frach L, Barkhuizen W, Allegrini AG, Ask H, Hannigan LJ, Corfield EC, et al. Examining intergenerational risk factors for conduct problems using polygenic scores in the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29:951–61.

Hughes AM, Torvik FA, van Bergen E, Hannigan LJ, Corfield EC, Andreassen OA, et al. Parental education and children’s depression, anxiety, and ADHD traits, a within-family study in MoBa. NPJ Sci Learn. 2024;9:46.

Ask H, Rognmo K, Torvik FA, Røysamb E, Tambs K. Non-random mating and convergence over time for alcohol consumption, smoking, and exercise: the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Behav Genet. 2012;42:354–65.

Ask H, Idstad M, Engdahl B, Tambs K. Non-random mating and convergence over time for mental health, life satisfaction, and personality: The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Behav Genet. 2013;43:108–19.

Pilkington PD, Milne LC, Cairns KE, Lewis J, Whelan TA. Modifiable partner factors associated with perinatal depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2015;178:165–80.

Ahmadzadeh YI, Eley TC, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D, et al. Anxiety in the family: A genetically informed analysis of transactional associations between mother, father and child anxiety symptoms. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60:1269–77.

McAdams TA, Rijsdijk FV, Neiderhiser JM, Narusyte J, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, et al. The relationship between parental depressive symptoms and offspring psychopathology: evidence from a children-of-twins study and an adoption study. Psychol Med. 2015;45:2583–94.

Ystrom H, Nilsen W, Hysing M, Sivertsen B, Ystrom E. Sleep problems in preschoolers and maternal depressive symptoms: An evaluation of mother-and child-driven effects. Dev Psychol. 2017;53:2261.

Ayorech Z, Cheesman R, Eilertsen EM, Bjørndal LD, Røysamb E, McAdams TA, et al. Maternal depression and the polygenic p factor: A family perspective on direct and indirect effects. J Affect Disord. 2023;332:159–67.

Bijma P. The quantitative genetics of indirect genetic effects: a selective review of modelling issues. Heredity (Edinb). 2014;112:61–9.

Kendall K, Van Assche E, Andlauer T, Choi K, Luykx J, Schulte E, et al. The genetic basis of major depression. Psychol Med. 2021;51:2217–30.

Smoller JW. The genetics of stress-related disorders: PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:297–319.

Cheesman R, Rayner C, Eley T The genetic basis of child and adolescent anxiety. In: Pediatric anxiety disorders. Elsevier; 2019. pp. 17–46.

Eilertsen EM, Jami ES, McAdams TA, Hannigan LJ, Havdahl AS, Magnus P, et al. Direct and indirect effects of maternal, paternal, and offspring genotypes: Trio-GCTA. Behav Genet. 2021;51:154–61.

Bjørndal LD, Eilertsen EM, Ayorech Z, Cheesman R, Ahmadzadeh YI, Baldwin JR, et al. Disentangling direct and indirect genetic effects from partners and offspring on maternal depression using trio-GCTA. Nature Mental Health. 2024;2:417-25.

Eilertsen EM, Cheesman R, Ayorech Z, Røysamb E, Pingault JB, Njølstad PR, et al. On the importance of parenting in externalizing disorders: an evaluation of indirect genetic effects in families. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022;63:1186–95.

Cheesman R, Eilertsen EM, Ahmadzadeh YI, Gjerde LC, Hannigan LJ, Havdahl A, et al. How important are parents in the development of child anxiety and depression? A genomic analysis of parent-offspring trios in the Norwegian Mother Father and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). BMC Med. 2020;18:284.

Stracke M, Heinzl M, Müller AD, Gilbert K, Thorup AAE, Paul JL, et al. Mental health is a family affair—systematic review and meta-analysis on the associations between mental health problems in parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:4485.

Magnus P, Birke C, Vejrup K, Haugan A, Alsaker E, Daltveit AK, et al. Cohort profile update: The Norwegian mother and child cohort study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:382–8.

Brandlistuen RE, Kristjansson D, Alsaker E, Valen R, Birkeland E, Røyrvik EC, et al. Cohort profile update: The Norwegian mother, father and child cohort (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol. 2025;54:dyaf139.

Paltiel L, Anita H, Skjerden T, Harbak K, Bækken S, Kristin SN, et al. The biobank of the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study–present status. Norsk Epidemiologi. 2014;24:1-2.

Corfield EC, Frei O, Shadrin AA, Rahman Z, Lin A, Athanasiu L, et al. The Norwegian Mother, Father, and Child cohort study (MoBa) genotyping data resource: MoBaPsychGen pipeline v.1. 2022.

Tambs K, Moum T. How well can a few questionnaire items indicate anxiety and depression?. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87:364–7.

Choi SW, Mak TS, O’Reilly PF. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat Protoc. 2020;15:2759–72.

Privé F, Arbel J, Vilhjálmsson BJ. LDpred2: better, faster, stronger. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:5424–31.

Allegrini A AndreaAllegrini/LDpred2[R] 2024 [Available from: https://github.com/AndreAllegrini/LDpred2.

International HapMap 3 Consortium. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467:52.

Purves KL, Coleman JR, Meier SM, Rayner C, Davis KA, Cheesman R, et al. A major role for common genetic variation in anxiety disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:3292–303.

Adams MJ, Streit F, Meng X, Awasthi S, Adey BN, Choi KW, et al. Trans-ancestry genome-wide study of depression identifies 697 associations implicating cell types and pharmacotherapies. Cell. 2025;188:640–52.e9.

Nagel M, Jansen PR, Stringer S, Watanabe K, De Leeuw CA, Bryois J, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nat Genet. 2018;50:920–7.

Demontis D, Walters GB, Athanasiadis G, Walters R, Therrien K, Nielsen TT, et al. Genome-wide analyses of ADHD identify 27 risk loci, refine the genetic architecture and implicate several cognitive domains. Nat Genet. 2023;55:198–208.

Watson HJ, Yilmaz Z, Thornton LM, Hübel C, Coleman JRI, Gaspar HA, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight risk loci and implicates metabo-psychiatric origins for anorexia nervosa. Nat Genet. 2019;51:1207–14.

Bezanson J, Edelman A, Karpinski S, Shah VB. Julia: A fresh approach to numerical computing. SIAM Review. 2017;59:65–98.

Eilertsen EM VCModels (1.0.0) [Julia] [Available from: https://github.com/espenmei/VCModels.jl.

Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52:317–32.

Vrieze SI. Model selection and psychological theory: a discussion of the differences between the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Psychol Methods. 2012;17:228.

Dominicus A, Skrondal A, Gjessing HK, Pedersen NL, Palmgren J. Likelihood ratio tests in behavioral genetics: Problems and solutions. Behav Genet. 2006;36:331–40.

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S, Christensen RHB, Singmann H, et al. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version 1.1-27-1. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4.

Ask H, Eilertsen EM, Gjerde LC, Hannigan LJ, Gustavson K, Havdahl A, et al. Intergenerational transmission of parental neuroticism to emotional problems in 8-year-old children: Genetic and environmental influences. JCPP Adv. 2021;1:e12054.

Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Gjessing HK, Skjaerven R, Melve KK, Schreuder P, et al. Self-selection and bias in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Norway. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23:597–608.

Funding

We would like to thank Freja Ulvestad Kärki at the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, The Norwegian Directorate of Health and Haakon Steen at Mental Helse for a valuable discussion of our results. MoBa is supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services and the Ministry of Education and Research. We are grateful to all the participating families in Norway who take part in this on-going cohort study. For generating high-quality genomic data, we thank the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), the HARVEST collaboration, the NORMENT Centre at the University of Oslo, the Center for Diabetes Research at the University of Bergen, deCODE Genetics, the Research Counsil of Norway, the South-Eastern and Western Norway Regional Health Authorities, the ERC AdG, Stiftelsen KG Jebsen, the Trond Mohn Foundation, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Data from the Norwegian Patient Registry has been used in this publication. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors, and no endorsement by the Norwegian Patient Registry is intended nor should be inferred. This work was performed on the TSD (Tjeneste for Sensitive Data) facilities, owned by the University of Oslo, operated and developed by the TSD service group at the University of Oslo, IT Department (USIT) (tsd-drift@usit.uio.no). The analyses were performed on resources provided by Sigma2 - the National Infrastructure for High-Performance Computing and Data Storage in Norway. The RCN supported Dr Pettersen, Mrs Johannessen and Drs Brandlistuen, Ask, Lund, Hegemann, Corfield, Andreassen, Havdahl and Ystrom (grants 324620, 274611, 324499, 324252, 336085, 336078, 288083, 331640). The South Eastern Regional Health Authority of Norway (Helse Sør-Øst) supported Drs Hannigan, Havdahl, Hegemann and Corfield (grants 2019097, 2020022, 2022083, 2021045). Nordforsk supported Drs Andreassen and Ystrom (grants 164218, 147386) and partly supported this work through the funding to Post-pandemic mental health: Risk and resilience in young people, project number 156298 (Drs Lund, Brandlistuen and Ask). The European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme (FAMILY) supported Dr Havdahl (grant 101057529), the European Union’s Horizon RIA grant supported Dr Andreassen (101057429) and The European Union supported Drs Eilertsen and Ystrom (GeoGen 101045526 and ESSGN 101073237). Dr Corfield is a member of the MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol which is supported by the Medical Research Council and the University of Bristol (MC_UU_00032/1). Open access funding provided by Norwegian Institute of Public Health (FHI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JHP, LJH, EE and HA conceptualized and designed the study. JHP drafted the manuscript. JHP and EE conducted statistical analyses. REB, EE and HA provided supervision. EE, LH, LJH, IOL, PMJ, ECC, EY, OAA, AH, REB and HA reviewed the manuscript and provided important feedback. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agents.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pettersen, J.H., Eilertsen, E., Hegemann, L. et al. Intra-familial dynamics of mental distress during the Covid-19 lockdown. Transl Psychiatry (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-026-03876-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-026-03876-z