Abstract

The emerging field of cancer neuroscience has demonstrated great progress in revealing the crucial role of the nervous system in cancer initiation and progression. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is characterized by perineural invasion and modulated by autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) and sensory innervations. Here, we further demonstrated that within the tumor microenvironment of PDAC, nociceptor neurons interacted with cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) through calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and nerve growth factor (NGF). This interaction led to the inhibition of interleukin-15 expression in CAFs, suppressing the infiltration and cytotoxic function of natural killer (NK) cells and thereby promoting PDAC progression and cancer pain. In PDAC patients, nociceptive innervation of tumor tissue is negatively correlated with the infiltration of NK cells while positively correlated with pain intensity. This association serves as an independent prognostic factor for both overall survival and relapse-free survival for PDAC patients. Our findings highlight the crucial regulation of NK cells by nociceptor neurons through interaction with CAFs in the development of PDAC. We also propose that targeting nociceptor neurons or CGRP signaling may offer a promising therapy for PDAC and cancer pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent studies have increasingly unveiled the pivotal role of the nervous system in the initiation and progression of cancer, fostering the establishment of an emerging field — cancer neuroscience.1,2,3,4 The development of cancer neuroscience offers additional therapeutic targets and strategies for combating cancer.5,6 Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is characterized by perineural invasion (PNI) with abnormal autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) and sensory innervations.7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Cancer pain is also the commonly presenting symptom of PDAC, ranking among the most severe types of pain.14 The role of sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation in PDAC progression has been extensively studied15; for sensory innervation, it was reported that ablation of sensory neurons prevents PNI and inhibits the formation or progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN); however, the broader mechanisms necessitates further exploration.16,17 It is reported that sensory neurons, especially nociceptor neurons, possess immunomodulatory properties. The spleen-innervating nociceptors promote the splenic germinal center response and humoral immunity.18 In a melanoma model, nociceptor neurons have been shown to suppress anti-tumor immunity by inducing the exhaustion of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells.19 Similarly, in sepsis and lethal pneumonia mouse models, nociceptor neurons inhibit the recruitment and surveillance of neutrophils, resulting in altered lung γδT cell numbers.20,21 Vagal sensory neurons have also been proved to promote immune homeostasis in the lung via JAK1 signaling.22 Thus, the impact of nociceptor neurons on cancer immunosurveillance in PDAC requires thorough investigation.

In the current study, we delved into the role and underlying mechanisms of nociceptor neurons in PDAC progression and cancer pain. Our findings demonstrate that nociceptor neurons interact with cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), subsequently suppressing natural killer (NK) cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) of PDAC and thereby fostering disease progression. Furthermore, inhibition of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) signaling through receptor activity modifying protein 1 (RAMP1) emerges as a promising therapeutic avenue for targeting PDAC and associated cancer pain.

Results

Ablation of nociceptor neurons suppresses the progression of PDAC

We first sought to explore the role of nociceptive innervation in PDAC development. To achieve this, we detected the distribution of CGRP+ nociceptive nerves in PDAC tissue or normal pancreas from patients receiving pancreatectomy and found significantly increased nociceptive innervation in PDAC tissue (Fig. 1a). Higher nociceptive innervation was also found in tumor tissue from orthotopic PDAC mice instead of the pancreas from naïve mice (Fig. 1b). Next, we chemically ablated nociceptor neurons in C57BL/6 mice using repeated injections of resiniferatoxin (RTX), a high-affinity transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) ligand following established protocols20,21 (Fig. 1c). The effects of denervation on nociceptor neurons were assessed using the hot plate test, revealing heat insensitivity — prolonged latency time to thermal stimulation in RTX-treated mice (Fig. 1d). After a 4-week recovery period, luciferin-labeled KPC#1 cells (5 × 104 cells per mouse) were inoculated into the mouse pancreas to establish the murine orthotopic PDAC model. Mice were observed for an additional 7 weeks to ensure adequate nerve innervation in TME. Tumor burden was measured through in vivo bioluminescent imaging at 1, 3, 5, and 7 weeks post tumor inoculation. Notably, RTX-treated mice displayed a lower local tumor burden, as evidenced by the total flux of KPC cells in tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 1e). Tumor tissues harvested after 7 weeks showed a significant reduction in tumor weight in the RTX group compared to vehicle group (Fig. 1f). In a separate experiment, RTX-induced nociceptor neuron ablation significantly prolonged overall survival time in tumor-inoculated mice (Fig. 1g). To confirm these findings, we established the PDAC model with a distinct KPC cell line (KPC#2). Similarly, RTX pretreatment markedly reduced the orthotopic tumor burden (Supplementary information, Fig. S1a–e). Moreover, we used the autochthonous PDAC murine model — KPC mice and administered vehicle or RTX when tumor was evident. The results showed decreased tumor weight in RTX-treated KPC mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S2a, b). These results collectively demonstrate that the chemical ablation of nociceptor neurons suppresses PDAC progression and improves prognosis.

a CGRP+ nociceptive nerves or β-tubulin III-labeled total nerves in normal pancreas or PDAC tissues from patients. Left, representative images of hematoxylin & eosin and immunofluorescence staining; right, quantification (n = 5 patients/group). Normal pancreas was obtained from the adjacent pancreatic tissues from patients with benign pancreatic lesion (serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas). Scale bar, 100 μm. The same sections were also stained for TH and ChAT (Supplementary information, Fig. S3g). b Expression of CGRP in murine normal pancreas and PDAC tissue. Top, representative images; bottom, quantification (n = 5 mice/group). Scale bar, 50 μm. c Experimental scheme for chemical ablation of TRPV1+ nociceptor neurons and tumor measurement. C57BL/6 mice at 4 weeks of age were treated with RTX (30 μg/kg, 70 μg/kg, and 100 μg/kg) subcutaneously for 3 consecutive days. Mice were rested for 4 weeks before orthotopic inoculation with KPC cells (5 × 104 cells/mouse) into pancreas. d Hot plate test to determine the heat sensitivity. Left, diagram of hot plate test; right, quantification of latency time (n = 8 mice/group). e In vivo bioluminescence of fluxes emitted by KPC cells in vehicle- or RTX-treated tumor-bearing mice at 1, 3, 5 and 7 weeks post inoculation. Left, images were obtained at 15 min after D-luciferin injection (30 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)); right, quantification of luciferase activity (n = 8 mice/group). f Tumor weights were compared between the vehicle and RTX groups. Left, images of tumors harvested 7 weeks post inoculation; right, quantification of tumor weight (n = 8 mice/group). g Survival analysis of tumor-bearing mice treated with vehicle or RTX (n = 10 mice/group). h Von Frey test measured the upper abdominal mechanical pain associated with cancer in mice treated with vehicle or RTX at baseline (BL), 3, 5, and 7 weeks after KPC inoculation. i CPA test was conducted to assess hypersensitivity to mechanical stimulation elicited by 0.02 g von Frey filament. Top, brief protocol of CPA test; bottom, representative traces and quantification (n = 7 mice/group). j Open field test was performed at 7 weeks after tumor inoculation to determine the distance (mm) and mean speed (mm/s) over a 20 min duration in vehicle- or RTX-treated mice (n = 7 mice/group). Top, representative traces; bottom, quantification. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; ns not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We also investigated various tumor-infiltrating nerve fibers via immunofluorescence staining in the TME of naïve mice or vehicle/RTX-treated mice. We observed increased innervations of various nerve fibers labeled by CGRP (peptidergic), IB4 (non-peptidergic), choline acetyltransferase (ChAT, parasympathetic), and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, sympathetic), as well as β-tubulin III (total nerve fibers) in the PDAC tissues of vehicle-treated mice, compared to pancreas of naïve mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S3a–f). The enhanced TH+ and ChAT+ nerve fiber innervation was also verified in human PDAC tissue compared to normal pancreas (Supplementary information, Fig. S3g, h). In RTX-treated PDAC tissue, the fluorescence signal of CGRP was significantly decreased, while the signals of markers of other types of nerve fibers (IB4, ChAT, TH and β-tubulin III) remained similar compared to those in mice exposed to the vehicle (Supplementary information, Fig. S3a–f). The loss of nociceptor neurons was further verified by RT-PCR with lower expression of TRPV1 and CGRP in the thoracic 9–13 (T9–13) dorsal root ganglion (DRG) from RTX-treated mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S3i–k). All of these results affirm the effective chemical ablation of nociceptor neurons, which leads to decreased CGRP positive innervation in the TME of PDAC.

Ablation of nociceptor neurons alleviates cancer-induced pain

Clinically, advanced PDAC patients often experience severe visceral pain and reduced mobility, resulting in functional impairment and a diminished quality of life.23 To investigate whether the ablation of nociceptor neurons could alleviate cancer-induced pain, mechanical allodynia was assessed through von Frey test on the right upper abdomen of PDAC mice at baseline, 3 weeks, 5 weeks, and 7 weeks after tumor inoculation according to reported protocols.24 Additionally, cancer-induced spontaneous pain was evaluated using the conditioned place aversion (CPA) test at 7 weeks post KPC cell injection. Our findings revealed that the ablation of nociceptor neurons significantly reduced mechanical allodynia and alleviated CPA induced by low threshold filament that is largely imperceptible to naïve mice (Fig. 1h, i). Attenuated mechanical allodynia was also detected in KPC mice treated with RTX (Supplementary information, Fig. S2c). Importantly, in the movement activity experiment by the open field test,24 mice treated with RTX exhibited greater overall movement distance and increased speed at 7 weeks after tumor inoculation (Fig. 1j). Thus, the ablation of TRPV1+ nociceptor neurons with RTX significantly alleviated cancer-induced visceral pain and improved locomotor function in PDAC mice.

Ablation of nociceptor neurons improves the infiltration and function of NK cells

Next, we aim to explore how PDAC progression is suppressed by the ablation of nociceptor neurons with RTX. Previous reports have revealed the expression of TRPV1 in various tumors, implicating its involvement in their progression.25 Consequently, we examined the direct effect of RTX on KPC cells in vitro. The IC50 curve for RTX on KPC cells was generated through CCK8 experiments, revealing an IC50 value of 8.3 μM, significantly higher than the concentration used in the current study (Supplementary information, Fig. S4a). RTX treatment did not induce changes in the proliferation and apoptosis of KPC cells, as evidenced by plate cloning assays and flow cytometry, when compared to vehicle treatment (Supplementary information, Fig. S4b, c). Additionally, RTX had no impact on the cell migration of KPC via a transwell experiment (Supplementary information, Fig. S4d, e). These results suggest that RTX does not directly inhibit the development of PDAC.

In prior studies, nociceptors were demonstrated to influence the recruitment and cytotoxicity of neutrophils and T cells in sepsis and melanoma mouse models. Here, we examined the alteration of immune cells in the TME following the chemical ablation of nociceptor neurons. Fresh tumor tissues from PDAC mice treated with either vehicle or RTX were collected for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to identify distinct cell types (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary information, Fig. S5a, b). Notably, the percentage of NK cells significantly increased following nociceptor neuron ablation, while the percentage of T cells remained similar between the vehicle and RTX-treated groups (Fig. 2c, d). Further analysis revealed heightened transcriptional expression of NK cell activation markers, TNF-α (Tnfa), IFN-γ (Ifng), and Granzyme B (Gzmb), in the TME of RTX-treated PDAC mice (Fig. 2e). These findings were validated in subsequent flow cytometry experiments, where the ablation of nociceptor neurons via RTX increased both the percentage and number of NK cells, while the percentage and number of CD3+ CD4+ T cells and CD3+ CD8+ T cells remained unchanged (Fig. 2f–i; Supplementary information, Fig. S6a–c). Moreover, the expression of TNF-α and Granzyme B (GrzmB) in NK cells of mice lacking innervation of nociceptor neurons was significantly higher than that in control PDAC mice (Fig. 2j, k). The increased infiltration of NK cells with enhanced activation was also detected in the tumor tissue from KPC mice after RTX treatment (Supplementary information, Fig. S2d–f). Regarding T cell activation, there was no difference in the expression of IFN-γ, GrzmB, and TNF-α in T cells of both groups (Supplementary information, Fig. S6d–f). However, the T cell exhaustion indicators like TIM3 and PD-1 were decreased after the ablation of nociceptor neurons (Supplementary information, Fig. S6g, h). These results suggest that the ablation of nociceptor neurons improves the infiltration and cytotoxic function of NK cells, as well as decreases exhausted T cells in the TME of PDAC.

a scRNA-seq was performed on murine PDAC tissues to determine the impact of nociceptive denervation on the TME. Cluster analysis with UAMP visualization: each color represents a cell group identified through clustering, with scatter points indicating individual cells. b Differences in cell populations revealed by integrated visualization. c Proportional analysis for NK cell through scRNA-seq. Left, proportion of NK cell in all the cell types. Right, proportion of NK cell from vehicle or RTX group in total NK cells from both groups. d Proportional analysis for T cell. Left, proportion of T cell in all the cell types. Right, proportion of T cell from vehicle or RTX group in total T cells from both groups. e Volcanic maps showed transcriptional expression of NK cell activation markers TNF-α (Tnfa), IFN-γ (Ifng), and granzyme B (Gzmb) in the TME of RTX-treated PDAC mice. The horizontal coordinate represents the difference of the pct value, the vertical coordinate represents the adjusted P value, and the color of the scatter plot represents the range of the log2FC (fold change) value. f Percentage of CD3– NK1.1+ cells in CD45+ cells by flow cytometry analysis. Left, representative images; right, quantification (n = 8 mice/group). g Percentage of CD3+ T cells in CD45+ cells. Left, representative images; right, quantification (n = 8 mice/group). h Representative images of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. i Comparison of percentages of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells in CD3+ T cells between vehicle and RTX groups (n = 8 mice/group). j, k Expression of the activation markers including TNF-α (j) and GrzmB (k) of NK cells. Left, representative images of flow cytometry; right, quantification (n = 8 mice/group). Data are shown as mean ± SEM; ns not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

We also assessed other immune cells involved in anti-tumor immunity through flow cytometry. No differences were observed in the percentage and number of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and macrophages in the tumor tissue from control mice compared to mice lacking nociceptive innervation (Supplementary information, Fig. S7a–d). To determine whether the immune modulation by nociceptor neurons is systemic or specific to the TME of PDAC, we examined changes in peripheral immune cells in the mouse spleen. No statistical differences were found in the percentage, activation, or exhaustion of peripheral NK cells and T cells between vehicle- and RTX-treated PDAC mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S8a–k). Similarly, there was no difference in the percentage of peripheral MDSCs and macrophages between two groups (Supplementary information, Fig. S9a, b). These findings demonstrate that the immune regulation by nociceptor neurons specifically targets the TME of PDAC rather than is systemic modulation.

Genetic or selective ablation of DRG nociceptor neurons suppresses PDAC via NK cell modulation

We next employed a genetic approach to ablate TRPV1+ neurons in mice. Trpv1-DTR mice were injected with diphtheria toxin (DTX) to denervate TRPV1+ neurons in DRG and vagal ganglia21,26 (Supplementary information, Fig. S10a). After a 7-day resting period, KPC cells were orthotopically inoculated, and a hot plate test was conducted to assess changes in heat sensitivity (Supplementary information, Fig. S10b). DTX-treated Trpv1-DTR mice exhibited significantly decreased local tumor burden and tumor weight at 5 and 7 weeks post tumor inoculation (Supplementary information, Fig. S10c, d). Concurrently, the TME of DTX-treated Trpv1-DTR mice showed the enhanced number of infiltrated NK cells and expression of NK cell activation markers such as TNF-α and GrzmB (Supplementary information, Fig. S10e, f). This genetic ablation approach further validates the role and mechanism of NK cell modulation via nociceptor neurons in PDAC.

Since the PDAC-innervating TRPV1+ nociceptive nerve mainly derives from thoracic DRG neurons,27,28,29 we further examined whether selective ablation of DRG nociceptor neurons would be enough to suppress PDAC growth via NK cell modulation. To this end, we injected mice intrathecally (i.t.) with RTX or vehicle to ablate TRPV1+ neurons in the thoracic DRG section26 (Supplementary information, Fig. S10g). Western blot verified the significantly decreased expression of TRPV1 in thoracic DRG of RTX-treated mice while the expression of β-tubulin III showed no statistical difference (Supplementary information, Fig. S10h). A significant reduction in local tumor burden and tumor weight at 5 and 7 weeks post tumor inoculation was observed in mice i.t. injected with RTX (Supplementary information, Fig. S10i, j). Meanwhile, increased infiltration of NK cells and expression of NK cell activation markers such as TNF-α and GrzmB (Supplementary information, Fig. S10k, l) were also found in RTX-treated mice. These results demonstrate that nociceptor nerves from DRG mainly play an immunomodulatory role in PDAC.

NK cells, but not T cells, mediate the inhibitory effect of nociceptor ablation on PDAC

Although the ablation of nociceptor neurons primarily influenced the infiltration and activation of NK cells, we also observed alterations in exhausted T cells within the PDAC tissue. To further validate the critical role of NK cells, rather than T cells, in the inhibition of PDAC resulting from the ablation of nociceptor neurons, we depleted NK cells through continuous anti-NK1.1 antibody injections30 in mice receiving either vehicle or RTX, and closely monitored the development of PDAC (Fig. 3a, b). In vivo imaging experiments demonstrated that the ablation of nociceptor neurons by RTX reduced the tumor burden of PDAC at 3, 5, and 7 weeks after tumor inoculation; however, this inhibitory effect was nullified when NK cells were depleted (Fig. 3c, d). Upon harvesting the tumor at 7 weeks after tumor injection, a decreased tumor weight was observed in RTX-treated mice, but not in mice treated with both RTX and anti-NK1.1 antibody (Fig. 3e, f). Flow cytometry confirmed the effective depletion of NK cells following anti-NK1.1 antibody administration and further demonstrated that the RTX-induced enhancement of NK cell infiltration into tumor tissues was abolished by the combined anti-NK1.1 treatment (Supplementary information, Fig. S11a–c).

a Anti-NK1.1 (250 μg/2 days, i.p.) antibody was administered after chemical ablation of nociceptor neurons and 1 day before orthotopic inoculation with KPC cells (5 × 104 cells/mouse) into pancreas. b Hot plate test was conducted to detect thermal hyperalgesia before and after vehicle or RTX treatment. c, d In vivo bioluminescence of fluxes by KPC cells in tumor-bearing mice was measured at 1, 3, 5, and 7 weeks post inoculation of KPC cells. Images were obtained at 15 min after D-luciferin injection (30 mg/kg, i.p.) (c) and luciferase activities were quantified (d). e Tumors harvested at the experimental endpoint were shown. f Comparison of tumor weight. g Experimental scheme for chemical ablation of nociceptor neurons in Rag1–/– mice and orthotopic inoculation of KPC cells (5 × 104 cells/mouse). h Heat sensitivity detected by hot plate test. i In vivo imaging showing the tumor burden of Rag1–/– mice treated with vehicle or RTX at indicated time points. Left, representative bioluminescence images; right, quantification of luciferase activity. j Tumors harvested at the experimental endpoint (left) and comparison of tumor weight (right). k Flow cytometry showing the number of infiltrated NK cells. l Expression of NK cell activation markers, including TNF-α and GrzmB, was compared between vehicle and RTX groups. n = 8 mice/group for b–f, and n = 7 mice/group for i–l. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; ns not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We also induced the ablation of nociceptor neurons through RTX treatment in Rag1–/–mice with deficiencies in T cells and B cells31 (Fig. 3g). The hot plate test indicated decreased thermal sensitivity in RTX-treated mice (Fig. 3h). Following orthotopic implantation of KPC cells, tumor growth was monitored. Remarkably, nociceptive denervation still exhibited suppression of tumor growth in these T cell-deficient mice (Fig. 3i, j), with enhanced infiltration and activation of NK cells in PDAC tissues (Fig. 3k, l). These findings underscore that NK cells, but not T cells, mediate the therapeutic effect of the ablation of nociceptor neurons on PDAC.

CGRP released from nociceptor neurons modulates NK cells contributing to PDAC progression

Nociceptors release neuropeptides such as CGRP and substance P (SP) from their peripheral terminals upon noxious stimulation.32 In the present study, scRNA-seq indicated that the expression levels of RAMP1 and calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CALCRL), the receptors of CGRP, were much higher than that of NK-1R, the receptor of SP, in PDAC tissue (Fig. 4a). The disparate expression of RAMP1, CALCRL, and NK-1R was further validated by western blotting (Fig. 4b). Since CGRP was reported to regulate neutrophils and lymphocytes,21,22,33 we hypothesized that CGRP might contribute to the NK cell-mediated tumor regression. We then detected the CGRP levels in pancreas and serum and found a significant increase in PDAC patients compared to non-PDAC patients (Fig. 4c; Supplementary information, Fig. S11d). The CGRP level also increased in PDAC mice while decreased in RTX-treated PDAC mice (Fig. 4c; Supplementary information, Fig. S11e). In vitro experiments showed that RTX with the dose range inhibiting the CGRP release from DRG neurons failed to influence the proliferation and activation of NK cells (Supplementary information, Fig. S11f–i), suggesting a direct effect of RTX on nociceptor neurons but not NK cells.

a scRNA-seq showing the expression of RAMP1, CALCRL and NK-1R in PDAC tissues. b Expression of RAMP1, CALCRL and NK-1R shown by western blot (n = 3/group). c CGRP level in normal pancreas or PDAC tissue from patients or mice (n = 5/group). Top, CGRP level in human tissue; bottom, CGRP level in murine tissue. d Experimental design to detect the effect of vehicle or Rimegepant (200 μg/2 days/mouse, intragastric gavage (i.g.)) treatment on PDAC mice. e In vivo bioluminescence of fluxes by KPC cells in tumor-bearing mice at 1, 3, 5, and 7 weeks after KPC inoculation. Images were obtained at 15 min after D-luciferin injection (30 mg/kg, i.p.) and representative images were shown. f Quantification of luciferase activity in e. g Comparison of harvested tumor weight. h Survival analysis of tumor-bearing mice treated with vehicle or Rimegepant (n = 10 mice/group). i Flow cytometry was performed to detect the proportion of NK cells and their activation in tumor tissue. j Von Frey test measured abdominal mechanical pain in mice treated with vehicle or Rimegepant at baseline (BL) and 3, 5, and 7 weeks after tumor inoculation. k CPA test was performed to gauge hypersensitivity caused by mechanical stimulation. Left, representative traces. Right, quantification of CPA score. l Open field test was conducted at 7 weeks after tumor inoculation to determine the distance (mm) and mean speed (mm/s) over a 20 min duration in both groups. Left, representative traces; right, quantification. n = 7 mice/group for e–g and i–l. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Rimegepant is an orally administered small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonist used clinically to treat migraines.34,35 Here we administered Rimegepant to PDAC mice at a dose of 200 μg per mouse every 2 days to block CGRP signaling (Fig. 4d). Observations on tumor progression indicated that Rimegepant treatment significantly decreased the tumor burden and improved the overall survival of PDAC mice compared to vehicle treatment (Fig. 4e–h). Mechanistically, in vitro experiments showed that CGRP did not affect the apoptosis and proliferation of KPC cells (Supplementary information, Fig. S12a, b). However, Rimegepant treatment increased the number of infiltrated NK cells and enhanced the expression of cytotoxic markers like TNF-α and GrzmB on NK cells in the TME of PDAC (Fig. 4i). This immune modulation is consistent with that observed after the ablation of nociceptor neurons via RTX. Given that Rimegepant did not directly activate NK cells in the in vitro experiment (Supplementary information, Fig. S12c–e), it is clear that blockade of the CGRP pathway mediates its anti-tumor immunity.

We also examined cancer-induced visceral pain and mobility function after CGRP blockade therapy. Von Frey test showed that application of Rimegepant could attenuate mechanical allodynia in PDAC mice at 7 weeks after tumor inoculation (Fig. 4j). In the CPA test, mice treated with Rimegepant exhibited alleviated ongoing spontaneous pain (Fig. 4k). Moreover, we observed improved movement ability via open field experiments in mice treated with Rimegepant compared to mice receiving vehicle treatment at 7 weeks after KPC implantation (Fig. 4l). Thus, blocking CGRP signaling could improve visceral pain and the quality of life.

To further verify the crucial role of CGRP, we employed Calca–/– mice with global knockout (KO) of CGRP to establish the orthotopic PDAC model (Supplementary information, Fig. S13a). Significant reduction of tumor burden was observed in Calca–/– mice at 5 and 7 weeks after tumor implantation, as compared to Calca+/+ mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S13b, c). The increased infiltration and activation of NK cells were also detected in PDAC tissues from Calca–/– mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S13d–f). Taken together, these results demonstrate that CGRP released from nociceptor neurons regulates NK cells engaging in the development of PDAC.

IL-15 mediates the modulation of CGRP on NK cells

Given that not only the infiltration but also the cytotoxic function of NK cells was upregulated in the TME of PDAC following CGRP blockade, we postulated that factors influencing the priming and activation of NK cells were involved. Consequently, we conducted a comprehensive screening of NK cell-related cytokines and chemokines via the analyses of the scRNA-seq data and RT-PCR data of the PDAC tissues from vehicle- or RTX-treated mice.36,37,38 Both analyses revealed heightened transcriptional expression of interleukin (IL)-2, IL-12, and notably, IL-15 in RTX-treated mice (Fig. 5a, b). This was further substantiated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), revealing a significant elevation in IL-15 levels after the ablation of nociceptor neurons (Fig. 5c). Gene ontology analysis of pathway enrichment from scRNA-seq also revealed that the ablation of nociceptive neurons in mice with PDAC upregulated the IL-15 production pathway (Fig. 5d). Moreover, in CGRP KO mice, the increase of NK cells was accompanied by higher level of IL-15 in PDAC tissue (Supplementary information, Fig. S13g).

a Bubble and violin plot visualization of cytokines and chemokines between vehicle and RTX groups at the scRNA-seq level. Left, violin plot. Right, quantitative bubble plot. The yellow to red color represents the increased expression level of the gene by Z-score, while the size of the bubble represents the percentage of cells with positive expression of the gene. b Cytokines and chemokines related to the chemotaxis and activation of NK cells were screened using RT-PCR (n = 3/group). c Interleukin levels in tumor tissue were further assessed using ELISA (n = 6 mice/group). d Gene ontology enrichment of signaling pathways showed that ablation of nociceptor enhanced IL-15 production in PDAC tissue. e Experimental scheme for anti-IL-15 antibody treatment. Anti-IL-15 antibody (200 μg) or control IgG was i.p. administered every 2 days from 1 day before KPC cell inoculation to the end of the experiment. f Thermal sensitivity was assessed using the hot plate test (n = 8 mice/group). g In vivo living imaging was conducted at 1, 3, 5, and 7 weeks after tumor implantation. Images were obtained at 15 min after D-luciferin injection (30 mg/kg, i.p.). h Quantification of luciferase activity (n = 8 mice/group) in g. i Tumors harvested at the experimental endpoint were shown. j Quantification of tumor weight (n = 8 mice/group) in i. k Flow cytometry showing the number of infiltrated NK cells. l Expression of NK cell activation markers, including TNF-α and GrzmB was compared (n = 8 mice/group). Data are shown as mean ± SEM; ns not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To test the hypothesis that IL-15 regulates NK cell function following the ablation of nociceptor neurons, we treated PDAC mice with anti-IL-15 antibodies to block the IL-15 pathway39 (Fig. 5e). The hot plate test confirmed the antinociceptive effect of RTX treatment (Fig. 5f). Tumor growth measurements demonstrated that RTX-induced ablation of nociceptor neurons reduced the tumor burden of PDAC, but this effect was nullified by concurrent treatment with anti-IL-15 antibodies (Fig. 5g–j). Flow cytometry analysis indicated an increase in the number of infiltrated NK cells in PDAC tissue after RTX treatment; however, this increase was attenuated with the simultaneous administration of anti-IL-15 antibodies (Fig. 5k). Further analysis revealed that combined anti-IL-15 antibody treatment could reverse the increased expression of NK cell activation markers, including TNF-α and GrzmB (Fig. 5l). These results suggest that IL-15 indirectly mediates the modulation of CGRP on NK cells.

CGPR inhibits IL-15 secretion from CAFs to suppress NK cells

We then asked how CGRP regulates IL-15 expression in the TME of PDAC. Through scRNA-seq analysis, we found that the receptors of CGRP, RAMP1, and CALCRL, were mainly expressed on CAFs of the TME, co-expressing with α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (encoded by Acta2) (Fig. 6a). Further analysis demonstrated that α-SMA-positive CAFs exhibited the highest expression of RAMP1 and CALCRL compared to other cell types including macrophages, Acta2-negative CAFs, NK cells, T cells, and tumor cells (Fig. 6b). Since the pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) are usually cultured and activated to obtain α-SMA+ CAFs in PDAC,40 we further examined the mRNA expression of RAMP1 and CALCRL in murine and human activated PSC cell lines and primary cultured PSCs. The results showed that the expression levels of RAMP1 and CALCRL on PSCs were 5–10 times higher than those on KPC cells, NK cells or CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6c). Western blot and immunofluorescence staining confirmed the expression of RAMP1 and CALCRL on murine and human CAFs, and their co-expression with α-SMA, respectively (Fig. 6d, e).

a Co-expression profiles of Ramp1 and Calcrl genes through a UMAP plot from scRNA-seq analysis. Top, Ramp1 marked in red and Calcrl in green, and yellow for the merged display. Bottom, the CAF cell population was visualized using UMAP and the expression of Acta2 was clustered after being highlighted; Acta2_positive circled in red and Acta2_negative in blue. b Expression levels of Ramp1 and Calcrl in distinct cell types visualized using a violin plot, where the horizontal coordinate represents different cell populations, and the vertical coordinate represents the average expression level. c mRNA expression of RAMP1 and CALCRL in murine and human activated PSC lines (mPSC and ihPSC) and primary cultured PSCs (pmPSC and phPSC). The KPC cells, NK cells, and CD8+ T cells were used as controls (n = 3 cultures/group). d Western blot demonstrating the RAMP1 and CALCRL expressions on PSCs and control cells. e Immunofluorescence staining showing the co-expression of RAMP1, CALCRL, and α-SMA in murine and human PSC cell lines and primary cultured PSCs. Scale bars, 100 μm or 200 μm as indicated. f ELISA was used to determine the effect of increasing concentrations of CGRP (0 nM, 0.1 nM, 1 nM and 5 nM) on the IL-15 expression in mPSCs after 24 h stimulation (n = 5 cultures/group). g, h IL-15 levels in mPSCs (g) or ihPSCs (h) after 24 h treatment of CGRP (1 nM) or combined with Rimegepant (Rime, 1 μM) by ELISA (n = 4 cultures/group). i IL-15 levels in mPSCs with vector (mPSC-v) or Ramp1 KO mPSCs after CGRP treatment (n = 5 cultures/group). j DRG neurons from mice treated with vehicle or RTX were co-cultured with mPSCs in the presence or absence of Rimegepant (1 μM). Left, diagram of experiments; right, levels of IL-15 released from mPSCs under the indicated conditions via ELISA (n = 4 cultures/group). k Levels of IL-15 in the co-culture medium of DRG neurons with mPSC-v or Ramp1 KO mPSC (n = 5 cultures/group). Data are shown as mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.001.

We next stimulated murine and human CAFs with increasing concentrations of CGRP. We found that CGRP significantly decreased the expression level of IL-15 in PSCs, as detected by ELISA (Fig. 6f; Supplementary information, Fig. S14a–c). However, co-incubation of Rimegepant with CGRP reversed the reduction of IL-15 induced by CGRP in both murine and human activated PSCs (Fig. 6g, h; Supplementary information, Fig. S14d, e). Rimegepant alone did not affect the IL-15 release from mPSCs (Supplementary information, Fig. S14f). Similarly, in mPSCs with Ramp1 KO, CGRP treatment failed to inhibit the IL-15 release (Fig. 6i; Supplementary information, Fig. S14g). In the co-culture system of PSCs and DRG neurons from vehicle-treated PDAC mice, the level of IL-15 in the co-culture medium significantly decreased compared to that in the medium of PSC cultured alone. IL-15 production was restored when Rimegepant was added to the co-culture system or PSCs were co-cultured with DRG neurons from RTX-treated mice (Fig. 6j; Supplementary information, Fig. S14h). Moreover, when DRG neurons were co-cultured with RAMP1-deficient mPSCs, the level of IL-15 was restored (Fig. 6k). We also treated KPC cells with various concentrations of CGRP; however, no change in IL-15 levels was observed, further confirming that IL-15 release from PSCs was modulated by CGRP (Supplementary information, Fig. S12f).

To further confirm the interaction between CGRP and CAFs to modulate NK cells via IL-15, we analyzed the IL-15 signaling pathway and outgoing interactions from the scRNA-seq data and found significantly increased IL-15 signal intensity between NK cells and CAFs in PDAC tissues from RTX-treated mice (Fig. 7a, b). We then introduced the culture medium of mPSCs treated with vehicle or CGRP into the NK cell culture system, and detected a significant inhibition in both the number and expression of cytotoxic markers of NK cells under CGRP treatment (Supplementary information, Fig. S15a–c). When culturing mPSCs, Ramp1 KO mPSCs, or IL-15 KO mPSCs with or without DRG neurons and then adding the culture medium to NK cells, we found that compared to medium of mPSCs alone or medium from the co-culture of DRG neurons with Ramp1 KO mPSCs, the co-culture medium of DRG neurons and mPSCs or the medium of IL-15 KO mPSCs hampered the proliferation and activation of NK cells (Fig. 7c, d; Supplementary information, Fig. S15d). We also directly administered increasing concentrations of CGRP to NK cells; however, no observable changes were noted in NK cell proliferation and activation markers, such as TNF-α and GrzmB (Supplementary information, Fig. S16a–c). These findings demonstrate that CGRP released from nociceptor neurons acts on CAFs to inhibit IL-15 secretion, consequently suppressing NK cells. This modulation occurs indirectly through CAFs rather than through direct interactions with NK cells in the TME of PDAC.

a Visualization of specific differences in the IL-15 signaling pathway between vehicle and RTX groups. The marked networks represent signal transmission and communication between cell subsets, and the signal intensity between cells is reflected by the thickness of the lines. b Visualization of cell communication signals: output signals between vehicle and RTX groups. The horizontal coordinate represents each cell group, and the vertical coordinate represents the top-ranked signaling molecules. The darker green in the heat map represents an increase in signal intensity. The histograms on the upper and right sides represent the summation of signal intensities. c Change of proliferaton of NK cells when treated with the culture or co-culture medium of DRG neuron, mPSC-v, Ramp1 KO mPSC, or IL-15 KO mPSC for 24 h (n = 5 cultures/group). d Expression of NK cell activation markers including TNF-α and GrzmB after the indicated co-incubation with culture medium by flow cytometry (n = 5 cultures/group). e Levels of NGF released from PSC or PSC co-cultured with DRG neurons (n = 5 cultures/group). f Levels of NGF in mPSC after vehicle, CGRP (1 nM) treatment or CGRP plus Rimegepant (Rime, 1 μM) treatment (n = 5 cultures/group). g NGF level in the co-culture medium of DRG neurons with mPSC-v or Ramp1 KO mPSC (n = 5 cultures/group). h Level of CGRP in DRG neurons after stimulation with increasing concentrations of NGF (n = 5 cultures/group). i Level of CGRP released from DRG neurons cultured alone or co-cultured with mPSCs or with mPSCs plus TrkA inhibitor (1 μM) for 24 h (n = 5 cultures/group). j Concentration of CGRP released from DRG neurons co-cultured with mPSC-v or Ngf KO mPSC for 24 h (n = 5 cultures/group). k Representative images of neurite outgrowth of DRGs treated with mPSC conditioned medium (left) and quantification of total length of neurites extending from DRG (right; n = 3 culture/group). Scale bar, 100 μm. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

CAFs release NGF to promote CGRP production in nociceptor neurons

CAFs were reported to release nerve growth factor (NGF) when activated by paracrine Sonic Hedgehog to foster PNI in PDAC.41 NGF/tropomyosin receptor kinase A (TrkA) pathway was also upregulated during PDAC development.42,43 From the scRNA-seq analysis, we further determined that NGF is predominantly expressed in CAFs, with significantly higher expression levels than in tumor cells and other cell types in murine and human PDAC tissues (Supplementary information, Fig. S16d–g). We then assayed the levels of NGF released from CAFs during co-culture with DRG neurons or direct stimulation with CGRP. The results showed elevated levels of NGF following the addition of DRG neurons or CGRP to PSCs, but decreased levels of NGF when PSCs were treated with Rimegepant or Ramp1 KO mPSCs were used (Fig. 7e–g). Increased level of NGF could in turn promote the CGRP production in DRG neurons (Fig. 7h). In the co-culture system of PSCs and DRG neurons, increased CGRP levels were detected compared to DRG neurons cultured alone, but this increase was reversed by TrkA inhibitor or NGF depletion in mPSCs (Fig. 7i, j; Supplementary information, Fig. S15e). The conditioned medium of mPSCs, particularly of CGRP-treated mPSCs, significantly enhanced the neurite outgrowth of DRG neurons and CGRP+ nociceptive neurons; however, this effect was abolished by the medium of Ngf KO CAFs (Fig. 7k; Supplementary information, Fig. S16h, i). Direct administration of NGF, though, did not affect the proliferation and activation of NK cells (Supplementary information, Fig. S16j–l). These findings collectively revealed the close communication between nociceptor neurons and CAFs in the TME, playing a crucial role in the progression of PDAC.

The nociceptive innervation in the TME is correlated with survival and cancer pain of PDAC patients

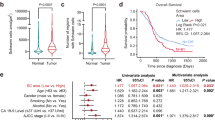

Lastly, we explored the association between nociceptor neuron innervation and the postoperative survival of PDAC patients. Multiplex fluorescent immunohistochemical staining was employed to identify the expression of α-SMA (labeling CAFs), RAMP1, CGRP in sensory nerves, and IL-15, as well as infiltration of NK cells (labeled by NCR1) in tumor tissues from PDAC patients (Fig. 8a). The number of NK cells in PDAC tissue was further quantified using flow cytometry. The results revealed that patients with high CGRP+ nociceptive innervation in the TME exhibited a decreased infiltration of NK cells and reduced immunofluorescence signal of IL-15 (Fig. 8b, c). The expression level of CGRP showed a negative correlation with the number of NK cells in PDAC (R = 0.365, P < 0.001) (Fig. 8d).

a Multiplex immunohistochemical staining of CGRP+ nociceptive nerve fibers, activated PSCs (labeled by α-SMA), RAMP1, IL-15, and infiltrated NK cells (labeled by NCR1) in tumors of PDAC patients. Based on the expression level of CGRP by immunofluorescence staining, patients were divided into CGRP low and CGRP high groups. Representative images with CGRP low and high expression were shown. Scale bar, 100 μm or 200 μm as indicated. b Flow cytometry was performed to detect NK cell infiltration into fresh tumor tissues obtained from PDAC patients undergoing surgical treatment (n = 22 patients in CGRP low group, n = 21 in CGRP high group). Representative images (left) and quantification (right) were shown. c Comparison of IL-15 levels by immunofluorescence staining in CGRP low and high patients (n = 22 patients in CGRP low group, n = 21 in CGRP high group). d Correlation between CGRP expression level and NK cell infiltration was calculated (n = 43 patients). e Based on the expression level of CGRP by immunofluorescence staining, patients were divided into CGRP low (n = 97 patients) and CGRP high (n = 78 patients) groups. Increased pain intensity was evaluated by NRS score in PDAC patients with high CGRP+ nociceptive innervation. f Associations between CGRP+ nociceptive innervation and OS or RFS. g Multivariate Cox regression was used to analyze independent risk factors associated with OS and RFS. h Graphical abstract. In the TME of PDAC, NGF from CAFs promotes the CGRP release from nociceptor neurons. CGRP further binds to the RAMP1 on CAFs and inhibits the expression of IL-15 to suppress the infiltration and cytotoxic function of NK cells, thus promoting PDAC progression and cancer pain. Data are shown as mean ± SEM or median with interquartile range; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Moreover, patients with elevated CGRP+ nociceptive innervation experienced more severe cancer pain, as determined by the numeric rating scale (NRS) score (Fig. 8e). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated that PDAC patients with high CGRP+ nociceptive innervation had reduced overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) (Fig. 8f). Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses further confirmed that CGRP+ nociceptive innervation is an independent prognostic factor for OS (HR, 2.278; 95% CI, 1.555–3.338) and RFS (HR, 1.782; 95% CI, 1.203–2.638) in PDAC patients (Fig. 8g; Supplementary information, Table S1).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that in the TME of PDAC, NGF from CAFs facilitates the secretion of CGRP from nociceptor neurons. CGRP further activates RAMP1 in CAFs and inhibits the expression of IL-15 to suppress the infiltration and cytotoxic function of NK cells, thus promoting PDAC progression and cancer pain (Fig. 8h). Targeting the nociceptor neurons or CGRP pathway might be a promising therapy for PDAC and cancer pain.

While the roles of sensory innervation in tumor progression have been increasingly studied, the underlying mechanisms and the involved cell types need further exploration.44 Immune regulation is a crucial aspect of the crosstalk between the tumor and the neural system. Traditionally, this regulation has been attributed to T cell differentiation, infiltration, and function. Sympathetic nerves have been reported to regulate tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes through β2-adrenergic receptor (ADRB2) on CD8+ T cells in melanoma.45 Catecholamines from sympathetic nerves contribute to CD8+ T cell exhaustion in melanoma and PDAC through the β1-adrenergic receptor (ADRB1).46 The synergy between β-blockers and immune checkpoint blockers enhances CD8+ T cell responses, inducing the development of tissue-resident memory-like T cells.46 In an orthotopic PDAC model, acetylcholine hindered PDAC cells from recruiting CD8+ T cells by inhibiting CCL5, directly suppressed IFNγ production, and promoted Th2 to Th1 differentiation.47 In a melanoma model, nociceptor neurons were found to suppress anti-tumor immunity by directly increasing the CGRP-mediated exhaustion of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. In our current research, we also observed reduced exhaustion of CD8+ T cells after RTX treatment; however, no corresponding increase in cytotoxic T lymphocytes and their cytotoxic function was detected. Remarkably, the anti-tumor effect of RTX-induced nociceptive denervation persisted in T cell-deficient mice. Meanwhile, the infiltration of NK cells and their cytotoxic function were significantly boosted after the ablation of nociceptive neurons, providing a new mechanism for the regulation of NK cells by PDAC innervation, distinct from the documented modulation of T cells.

It has been reported that RTX may cause off-target effects due to the widespread expression of TRPV1 in various tissues, such as neurotoxicity from non-specific neuronal damage, cardiovascular stimulation, respiratory disturbances, and hypothermia.48,49,50 In this study, we strictly followed a well-established protocol for nociceptor neuron ablation, using young mice (4 weeks old), administering multiple subcutaneous injections with increasing doses, and closely monitoring their status.19,20,21 All mice were given 4 weeks to recover before further experiments. As a result, no obvious side effects were observed, and no mice were excluded from the study after RTX treatment.

CAFs constitute major components of the PDAC stroma, influencing desmoplasia, angiogenesis, immune evasion, and drug resistance.40,51 CAFs activated by paracrine Sonic Hedgehog display significantly increased levels of matrix metalloproteinases and NGF, promoting PNI in PDAC.41 Co-cultivation of PSCs with lymphocytes inhibits spontaneous lymphocyte apoptosis through IL-15 expressed on PSCs, and this effect is reduced by an anti-IL-15 antibody.52 IL-15 also plays a pivotal role in enhancing NK cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and NK cell therapies.53,54 Thus, it is possible that CAFs regulate neuroimmune reconstitution of the TME in PDAC. In the current study, we provided further evidence that CAFs drive CGRP production in nociceptor neurons via NGF. CGRP then hinders the release of IL-15, contributing to the immune suppression of NK cells. To be noted, various tumor-derived factors such as secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and NGF could also activate CGRP production in nociceptor neurons, which in turn triggers the positive feedback loop of nociceptor and CAF.19,55,56 Future studies should investigate the temporal and mechanistic initiation of nerve–CAF interactions during early carcinogenesis to fully understand their role in tumor progression.

Interestingly, a recent study by Kobayashi et al. also investigated nerve–CAF interactions in colorectal cancer (CRC).57 They found that sympathetic nerve stimulation induces NGF secretion from CAFs, leading to increased tumor innervation and promoting tumor progression. Adrenergic stimulation promotes CRC growth through α2-adrenergic receptor-mediated activation of Yes-associated protein, and NGF boosts CRC cell growth via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway.57 While our study focuses on immune suppression via nociceptor neuron–CAF interactions, Kobayashi et al. emphasize their direct impact on tumor cell biology. Collectively, both studies underscore the critical role of nerve–CAF crosstalk in modulating immune responses and tumor growth, highlighting the potential for targeting this interaction as a therapeutic strategy in distinct cancers.

Pain is one of the most severe and debilitating symptoms associated with advanced or metastatic cancer. The mechanisms of cancer pain are complex, presenting in various forms such as somatic, neuropathic, and visceral pain.58 Nerve hyperinnervation plays a crucial role in carcinogenesis and cancer pain, and targeting NGF, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or granulocyte and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors has been shown to inhibit nerve sprouting and alleviate cancer pain.59,60,61 Here, we further highlight the role of CGRP+ nociceptor neurons in PDAC-related visceral pain. We also utilized the novel orally-dosed RAMP1 antagonist Rimegepant and observed both NK cell activation-mediated anti-tumor and antinociceptive effects in PDAC mice. Importantly, Rimegepant has been approved by the FDA for the acute treatment of migraine in adults.34,35 Considering that our clinical data showed a correlation between high CGRP innervation and poor prognosis and severe pain, the application of Rimegepant to PDAC patients might be a promising therapeutic approach and warrants clinical trials for verification.

There are several limitations to this study that should be acknowledged. First, although we utilized two cell lines and KPC mice to verify the main findings, the majority of experiments were conducted with a single PDAC cell line. Additionally, the absence of conditional KO models, such as Ramp1 or Ngf deletion specifically in CAFs, limits the in vivo evidence supporting the proposed mechanisms. Second, due to the relatively small sample size of the clinical study, the prognostic significance of CGRP+ nerves on patient survival requires further validation in larger PDAC cohorts. Lastly, while we identified a significant correlation between nociceptive innervation and NK cell infiltration in human PDAC tissues, we did not examine potential interactions with CD8+ T cells. This restricts our conclusions on the regulation of NK cells within the specific models used. Given that CD8+ T cell activity often correlates more strongly with therapeutic responses, future investigations should explore the role of nociceptor neurons in modulating both NK and T cells, as well as other immune components, using diverse tumor models and patient cohorts with multiple tumor types.

Materials and methods

Cell line

The mouse KPC cell line was derived from PDAC in LSL-KrasG12D;LSL-Trp53R172H;Pdx1-Cre (KPC#1) mice and identified by short tandem repeat analysis. The KPC#2 cell line (LSL-KrasG12D/+;LSL-Trp53R172H/+;Pdx1-Cre) from KPC mouse was a gift from Dr. Shengyu Yang (Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Penn State University College of Medicine, USA). The mouse PSC cell line (mPSC) was purchased from Kanglang Biological Technology Co., Ltd (KL-PC1033M). The immortalization of human PSC (named Immortal Human PSC (ihPSC)) was achieved by transfection of SV40 large T antigen and human telomerase.62 All these cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 (KPC#1 and KPC#2) (Gibco, C11875500BT) or DMEM (mPSC and ihPSC) (Gibco, C11995500BT) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, 10099141), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco, 10378016) in a humidified incubator at 37 °C. KPC cell lines were tested for CR-mediated mutant Kras and Trp53 allelic recombination using PCR63 (Supplementary information, Fig. S17a). The primer sequences for detecting recombinant Kras and Trp53 sites were shown in Supplementary information, Table S2. All the cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination every 6 months using a mycoplasma kit (Solarbio, CA1080).

Animals and tumor models

All animal experimental procedures adhered to the approved protocols by the IACUC and Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital (Approval# YYJC-AE-2022016). Four-week-old C57BL/6J and Rag1–/– mice were procured from GemPharmatech LLC. C57BL/6Smoc-Calcaem1Smoc mice were ordered from Southern Model Animal Company in Shanghai, China. The TRPV1-Cre (B6.129-Trpv1tm1(cre)Bbm/J) and DTR (C57BL/6-Gt (ROSA)26Sortm1(HBEGF)Awai/J) mice were donated by Prof. Zilong Wang (Southern University of Science and Technology, China). KPC mice (C57BL/6Smoc-Trp53 em4(R172H) Kras em4(LSL-G12D) Tg (Pdx1-Cre) Smoc mice) were purchased from Shanghai Model Organisms Center.

All tumor cell lines were implanted during exponential growth. Mouse orthotopic model of PDAC was established in situ as follows: Initially, a luciferin-labeled KPC cell suspension containing 5 × 104 cells per mouse was prepared. The KPC cell suspension was formulated using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and matrix glue (BD, 356234). Subsequently, mice were anesthetized using 2% isoflurane (RWD, R510-22) at a fresh gas flow rate of 4 L/min. Once the mice were under anesthesia, the left side of the abdomen was subjected to disinfection using Geriodide disinfectant for three times. With autoclaved scissors, the skin and peritoneum were successively incised to expose the pancreatic tissue. The cell suspension was meticulously injected into the mouse pancreas, ensuring a maximal volume of 40 μL to prevent leakage. Following the injection, the pancreas was gently repositioned within the peritoneal cavity. The abdominal wall and skin were carefully sutured using surgical sutures to complete the procedure. The survival time of each mouse was recorded and evaluated using Kaplan-Meier method. Tumor weight was determined upon harvest.

Ablation of TRPV1+ nociceptor neurons

For chemical ablation of TRPV1+ nociceptor neurons, 4-week-old C57BL/6 wild-type mice were treated with RTX (Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., S25831). RTX was prepared by dissolving in a solution containing 2% dimethyl sulfoxide (Solarbio Life Sciences, D8370) and 0.15% Tween-80 (Solarbio, T8360) in PBS (Solarbio, D1040), and the solution was stored at –80 °C. Over the course of three consecutive days, mice received subcutaneous injections in the flank with escalating doses of RTX (30 μg/kg, 70 μg/kg, and 100 μg/kg). The mice in the control group received only the vehicle solution. Ablation of TRPV1+ nociceptor neurons was confirmed 28 days after RTX treatment by a lack of pain withdrawal reflex when mice were exposed to a hot plate. For KPC mouse model, the development of pancreatic cancer in these mice was monitored by ultrasound scans (Canon Aplio i800, Japan). Mice with tumor volumes of 20–60 mm³ were randomly assigned into vehicle group and RTX group as described above. For genetic ablation of nociceptor neurons, Trpv1-DTR mice were treated with DTX. DTX (200 ng) was dissolved in 100 μL PBS and i.p. injected daily for 21 days with PBS injection as control. To target ablation of DRG TRPV1+ neurons, C57BL/6 mice were injected i.t. with RTX (25 ng/mouse) using a 30G needle and an airtight syringe in the T9–T13 region for two consecutive days. Female mice aged 4 weeks were selected for the experiments.

NK cell depletion

To deplete NK cells in mice, an anti-NK1.1 antibody (Selleck, A2114) was administered via intraperitoneal injection at a dosage of 250 μg in 100 μL of PBS every 2 days.30 The treatment regimen commenced 1 day prior to the orthotopic tumor transplantation and continued until the end of the experiment. Flow cytometry was used to confirm the significant decrease of NK cells after treatment (Supplementary information, Fig. S17b).

IL-15 neutralization

To deplete IL-15 in mice, we obtained an anti-IL-15 antibody from BioXCell (BE0315). Following a protocol from a previous report,39 mice received intraperitoneal injections of 200 μg of anti-IL-15 neutralizing antibody or isotype control antibody IgG2a (BioXCell, BP0089) every 2 days from 1 day before KPC inoculation to the end of the experiment.

CGRP receptor blockade

For CGRP receptor blockade in vivo, C57BL/6 mice with tumor were administered 200 µg of Rimegepant (BMS-927711, APEXBIO, A3259) orally every 2 days from 1 day before KPC inoculation to the end of the experiment. The dose was calculated referring to previous studies using the metrological conversion formula between human and mouse according to a previous report.34

Live animal imaging

Tumor growth was analyzed by bioluminescent imaging. D-luciferin (Genomeditech, GM-040611) was employed for the study. About 15 min after intraperitoneal injection of 30 mg/kg of D-luciferin, bioluminescent images of tumor-bearing mice were captured via the IVIS Lumina III system. The bioluminescence images were analyzed using the Living Image software provided by PerkinElmer.

Behavioral tests

All the behavioral tests were conducted in a blinded manner and performed during 9:00–16:00. Animals were habituated in a light- and humidity-controlled testing environment for at least 2 days prior to baseline testing.

Hot plate test

Mice were positioned on a 53 °C hot plate (Zhenghua, Anhui, China) enclosed within a transparent plexiglass cylinder. The latency time for heat sensitivity was defined as the time between placing the mice on the hot plate and their avoidance response to heat-induced pain, such as jumping or paw licking. A maximum cutoff value of 40 s was set to avoid thermal injury.

Von Frey test

Mechanical pain was assessed using von Frey filaments, following a methodology outlined in a previous report.24 On the testing day, mice were allowed to acclimate in the test box for 2 h without any interventions. Subsequently, 0.02 g von Frey filament was repeatedly applied to the abdomen (10 times, with ~1–2 min between each stimulation) and the frequency of abdominal nociceptive responses was measured.

CPA assay

As previously reported,64,65 a modified CPA assay was employed in the current study. Mice were introduced to a customized two-chamber (red or white walls) apparatus positioned on an elevated grid floor for habituation over 3 days (30 min each). Baseline preference was video-recorded for 10 min and movement was tracked using the VisuTrack software 2.0 (Xinruan, Shanghai, China) on the final day of the habituation. All mice displayed < 65% preference for either chamber, thus allowing for the inclusion of all mice with baseline recordings in the experiment. Mice were then isolated in their favored chamber. Pairing was initiated by using a 0.02 g von Frey filament to gently stimulate the abdomen in a repeated manner every 10 s for 10 min. This stimulus was designed to be minimally intrusive. Subsequently, the mice were given a 10-min resting period in their cages, after which they were reintroduced to the CPA chamber, where they were allowed to resume moving freely between chambers for 10 min. VisuTrack software 2.0 was used for the analysis of the recorded video. The time ratios of mice in their preferred chambers before and after stimulation were calculated and compared.

Open field test

Mouse locomotor function was evaluated using the open field test. Mice were placed within a 50 cm × 50 cm chamber and their locomotor activity was video-recorded via an overhead camera connected to a computer system. VisuTrack software 2.0 was used to automatically track and record mouse movements for a 20-min period.

Cell preparation for scRNA-seq

PDAC tissues from RTX- or vehicle-treated mice were collected, with 3 mice in each group. Tumorigenesis and growth were monitored using non-invasive in vivo imaging. Significant differences in tumor burden were observed at 7 weeks after tumor inoculation, and the PDAC tissues were dissected and sampled then. The tissue was washed in ice-cold RPMI 1640 and dissociated using Tissue Dissociation Reagent A (Seekone, K01801-30) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNase I treatment (Sigma, 9003-98-9) was optional based on the viscosity of the homogenate. Cell count and viability were assessed using a fluorescence Cell Analyzer (Countstar® Rigel S2) with AO/PI reagent after erythrocyte removal (Solarbio, R1010). Finally, fresh cells were washed twice in RPMI 1640 and resuspended at 1 × 106 cells/mL in 1× PBS and 0.04% bovine serum albumin. Subsequently, viability test can distinguish immune cells, fibroblast cells, and tumor cells based on cell density and size. Library construction and sequencing were performed when cell viability reached above 90%, with a total of 500,000 viable tumor cells per gram before dissociation and a clustering rate of < 5%.

scRNA-seq library construction and sequencing

scRNA-seq libraries were prepared using the SeekOne® Digital Droplet Single Cell 3′ library preparation kit (SeekGene, K00202). In brief, an appropriate number of cells were mixed with reverse transcription reagent and added to the sample well in the SeekOne® chip. Barcoded Hydrogel Beads (BHBs) and partitioning oil were dispensed into corresponding wells separately in the chip. After emulsion droplet generation, reverse transcription was performed at 42 °C for 90 min and then terminated at 80 °C for 15 min. Next, cDNA was purified from broken droplets and amplified in a PCR reaction. The amplified cDNA product was then cleaned, fragmented, end-repaired, A-tailed, and ligated to sequencing adapters. Finally, indexed PCR was performed to amplify the DNA representing the 3′ polyA part of expressing genes, which also contained Cell Barcode and Unique Molecular Index. The indexed sequencing libraries were cleaned up with SPRI beads, quantified by quantitative PCR (KAPA Biosystems, KK4824), and then sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with PE150 read length. The specific analysis process and details of single-cell sequencing are presented as follows: First, we screened and enriched the highly variable characteristic genes. A subset of genes with high variability between cells was calculated using the R package seurat, and 2000 genes with the highest degree of variation were selected for downstream analyses. Subsequently, cell dimension reduction clustering and principal component analysis were performed. Principal component parameters were calculated, and the most significant components were filtered based on enrichment and P-value. Nonlinear dimensionality reduction analysis using TSNE or UMAP algorithms was performed to cluster cells into several classes. Finally, intercellular communication analysis was conducted to reveal the signal communication between the microenvironment cell subsets. Cellular communication was analyzed and visualized using the R package CellChat, which contains a database of signaling molecules and is used for differential expression analysis and statistical tests.

Analysis for human PDAC scRNA-seq dataset

The scRNA-seq data of 24 patients were downloaded from CRA001160 dataset. Seurat R package was used to screen for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) to obtain trajectories and subclusters with biological significance. UMAP was used to map high-dimensional gene expression data from scRNA-seq to low-dimensional space. The DEGs were shown using bubble plot in the ggplot2 package, and the distribution of cells in space was observed.

Primary NK cell isolation and culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were separated from the spleens of C57BL/6 mice within 30 min of collection using Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation (DAKEWE, 7211011). Primary NK cells were then enriched by negative selection using a MACS NK cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-115-818). Primary NK cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 5% horse serum, 5% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 500 U/mL IL-2 (absin, abs05280), and 20 ng/mL IL-15 (absin, abs01328). All the primary cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Co-culture of DRG neurons and PSCs

DRG neurons and PSCs were indirectly co-cultured in 6-well plates for 24 h. DRG neurons (2 × 105) were suspended in the lower chamber medium containing 10% FBS, and PSCs (2 × 105) were suspended in the upper chamber medium containing 10% FBS. In addition, Rimegepant (1 μM) was used to block the CGRP-RAMP1 signaling, and 1 μM of the selective TrkA inhibitor (GW441756, Selleck Chemicals, Munich, Germany) was added to the cultures for the inhibition of TrkA signaling. Finally, the levels of IL-15, NGF, and CGRP were detected by ELISA through collecting supernatant.

ELISA

ELISA for CGRP (CUSABIO, CSB-EQ027706MO), NGF (Elabscicence, E-EL-M0815c), IL-2 (Neobioscience, EMC002), IL-12 (Neobioscience, EMC006) or IL-15 (Neobioscience, EMC126) was performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry

For flow staining, fresh tumor tissues were collected, digested in serum-free cell medium containing 1 mg/mL collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich, C4-22) and 100 μg/mL DNase I (SparkJade, AC1711) at 37 °C for 40–60 min, and then ground into single-cell suspension. The mouse spleen was directly ground into a single-cell suspension. Subsequently, surface antibodies anti-CD45, anti-CD3, anti-CD8, anti-CD4, anti-NK1.1, anti-CD56, anti-TIM-3, anti-PD-1, anti-Ly-6G, anti-Ly-6C, anti-F4/80 and anti-CD11b were added at a 1:100 dilution in PBS containing 1% FBS and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. For intracellular cytokine staining in tumor tissues, cells were stimulated with Leukocyte Activation Cocktail (BD, 55083) in a 37 °C, humidified CO2 incubator for 4 h. Then, intracellular cytokines were stained with anti-TNF-α, anti-IFN-γ, and anti-GrzmB after the cells were treated using a Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Fixation/Penetration kit (BD, 554717) at a 1:100 dilution and adjusted to a final volume of 250 µL. Data acquisition was performed using the BECKMAN CytoFLEX LX flow cytometry, and analysis was performed using CyExpert. Apoptosis of tumor cells was assessed using the APC-Annexin V/PI apoptosis kit (UElandy, A6030L). Data acquisition was performed using BD FACSCanto II (BD) and analyzed using Flowjo 10.

For more information of antibodies and the gating strategies for flow cytometry experiments, please refer to Supplementary information, Table S3 and Fig. S17c.

Immunofluorescence staining

For frozen sections, Leica CM1860 cyrostat was used to prepare sections with a thickness of 20 μm. The section was antigen repaired and blocked for 2 h using 20% donkey serum (Solarbio, S9100) in 0.5% Triton X-100/PBS. The following primary antibodies were used for nerve staining, including anti-TH antibody (Boster, PB9449), anti-CGRP antibody (Abcam, ab181887), anti-ChAT antibody (Proteintech, 24418-1-AP) and anti-β-tubulin III antibody (TUBB III) (Boster, BM3881), used at 1:100 dilution in 2% donkey serum with 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for 48 h at 4 °C. Anti-NCR1 antibody (Abcam, 199128), anti-IL-15 antibody (Proteintech) and anti-RAMP1 antibody (Thermo Fisher, PA5-110265) require overnight incubation at 4 °C. The section was washed three times with TBST to remove the primary antibody, and incubated with the secondary antibody at 1:100 dilution in 2% donkey serum with 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS. For paraffin sections, 4-μm thick sections were prepared using Leica RM2235 rotary microtome. Multiple fluorescent staining of paraffin tissues was performed using the Opal 7-Color Manual IHC kit (Akoya, NEL811001KT) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For ISOLECTIN GS-IB4, Alexa Fluor 647 (Sigma, L2895) was dissolved in PBS solution at 1:50 dilution and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The slides were mounted with Fluoromount-G medium containing diamidino phenylindole (DAPI) (Southern Biotech, 0100-20). Images were collected on a KEYENCE microscope (KEYENCE BX-Z800 series) using either 10× or 20× air objectives. Five images of different fields of view were randomly selected from each section, and the nerve density was calculated by quantifying the percentage of the total fluorescence area of nerve fibers to the fluorescence area of DAPI by ImageJ, and the average value was calculated (each point represents a mouse in the figure).

Cell fluorescence

The cells were inoculated into a 24-well plate containing climbing tablets at the optimal concentration. After the cells were stuck to the wall, they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10–15 min and rinsed with PBS three times. Triton X-100 permeates cells and enhances cell membrane permeability. Fluorescence staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using primary antibodies anti-RAMP1 (Thermo Fisher, PA5-110265, at 1:100 dilution), anti-CALCRL (alomone, ACC-060, at 1:200 dilution) and anti-α-SMA (Abcam, ab7817, at 1:100 dilution), and secondary antibody of goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor™ 488 (Invitrogen, A11001) or goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor™ Plus 594 (Invitrogen, A32740). Figures and data were collected on a KEYENCE microscopy (KEYENCE BX-Z800 series) using a 40× lens.

Patients and samples

All patients provided written informed consent. The use of these tissues and patient information was authorized by the Ethics Committee of the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital (Approval# Ek2022279). Tumor samples were retrospectively analyzed from 175 PDAC patients treated at the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital from 2016 to 2017, which were archived in the Biobank after adequate informed consents were obtained. Forty-three cases of fresh PDAC tissues were prospectively collected in 2022 for flow cytometry and immunofluorescence staining. All these patients underwent radical resection of pancreatic cancer with R0 margins confirmed by 2 pathologists. None of the patients had received chemotherapy or radiotherapy at the time of sample collection. All patients received gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy for at least 6 cycles. Normal pancreatic tissues from patients with benign diseases were subjected to pancreatic resection surgery. Ten fresh tissue samples were used to assess differential expression of CGRP in normal pancreas (n = 5) and PDAC (n = 5). Patient blood samples were collected before surgery and used for ELISA. The NRS scores at the initial diagnosis of PDAC before cancer treatment and pain medication were recorded to assess pain intensity. NRS is widely recognized as a reliable and convenient tool for pain assessment in clinical trials, with strong correlations with other validated instruments.66,67 An NRS score of 3 was further set as the cutoff threshold to identify mild pain or moderate to severe pain.68 Postoperative follow-up for patients was conducted every 3 months initially. OS was defined as the time interval from the date of surgery to that of death due to any cause or that of the last follow-up. RFS was calculated from the date of surgery to that of local recurrence or metastasis. Local recurrence or metastasis was diagnosed by radiological examination (contrast-enhanced CT or MRI scanning).

Statistical analysis and software

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 and GraphPad Prism v9.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.). The statistical significance was determined using unpaired Student’s t-test (two-tailed), one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test, or as indicated in figure legends. Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate OS or RFS at different CGRP expression levels in PDAC and the difference between survival rates was examined by the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to assess the relationship between different factors and OS/RFS. Each mouse was considered a separate biological sample. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Deidentified scRNA-seq raw data are available from the National Genomics Data Center (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/subcenter/1) under accession number OEP005530 (Shared URL: https://www.biosino.org/node/project/detail/OEP005530). Further information related to the data reported in this paper can be acquired from the lead contact Jihui Hao (haojihui@tjmuch.com) upon reasonable request.

References

Monje, M. et al. Roadmap for the emerging field of cancer neuroscience. Cell 181, 219–222 (2020).

Winkler, F. et al. Cancer neuroscience: state of the field, emerging directions. Cell 186, 1689–1707 (2023).

Mancusi, R. & Monje, M. The neuroscience of cancer. Nature 618, 467–479 (2023).

Wang, K. et al. STING suppresses bone cancer pain via immune and neuronal modulation. Nat. Commun. 12, 4558 (2021).

Hanahan, D. & Monje, M. Cancer hallmarks intersect with neuroscience in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 41, 573–580 (2023).

Shi, D. D. et al. Therapeutic avenues for cancer neuroscience: translational frontiers and clinical opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 23, e62–e74 (2022).

Ferdoushi, A. et al. Tumor innervation and clinical outcome in pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 11, 7390 (2021).

Kondo, N. et al. An increased number of perineural invasions is independently associated with poor survival of patients with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 44, 1345–1351 (2015).

Crippa, S. et al. Implications of perineural invasion on disease recurrence and survival after pancreatectomy for pancreatic head ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. 276, 378–385 (2022).

Hinshaw, D. C. & Shevde, L. A. The tumor microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res. 79, 4557–4566 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Role of the nervous system in cancers: a review. Cell Death Discov. 7, 76 (2021).

Demir, I. E. et al. Targeting nNOS ameliorates the severe neuropathic pain due to chronic pancreatitis. EBioMedicine 46, 431–443 (2019).

Ceyhan, G. O. et al. Pancreatic neuropathy results in “neural remodeling” and altered pancreatic innervation in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 104, 2555–2565 (2009).

Grossberg, A. J. et al. Multidisciplinary standards of care and recent progress in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70, 375–403 (2020).

Ni, B. et al. Crosstalk between peripheral innervation and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Neurosci. Bull. 39, 1717–1731 (2023).

Saloman, J. L. et al. Ablation of sensory neurons in a genetic model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma slows initiation and progression of cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 3078–3083 (2016).

Sinha, S. et al. PanIN neuroendocrine cells promote tumorigenesis via neuronal cross-talk. Cancer Res. 77, 1868–1879 (2017).

Wu, M. et al. Innervation of nociceptor neurons in the spleen promotes germinal center responses and humoral immunity. Cell 187, 2935–2951.e19 (2024).

Balood, M. et al. Nociceptor neurons affect cancer immunosurveillance. Nature 611, 405–412 (2022).

Pinho-Ribeiro, F. A. et al. Blocking neuronal signaling to immune cells treats streptococcal invasive infection. Cell 173, 1083–1097.e22 (2018).

Baral, P. et al. Nociceptor sensory neurons suppress neutrophil and γδ T cell responses in bacterial lung infections and lethal pneumonia. Nat. Med. 24, 417–426 (2018).

Tamari, M. et al. Sensory neurons promote immune homeostasis in the lung. Cell 187, 44–61.e17 (2024).

Ceyhan, G. O. et al. Pancreatic neuropathy and neuropathic pain—a comprehensive pathomorphological study of 546 cases. Gastroenterology 136, 177–186.e1 (2009).

Selvaraj, D., Hirth, M., Gandla, J. & Kuner, R. A mouse model for pain and neuroplastic changes associated with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pain 158, 1609–1621 (2017).

Li, L. et al. The impact of TRPV1 on cancer pathogenesis and therapy: a systematic review. Int J. Biol. Sci. 17, 2034–2049 (2021).

Lai, N. Y. et al. Gut-innervating nociceptor neurons regulate Peyer’s Patch Microfold cells and SFB levels to mediate Salmonella host defense. Cell 180, 33–49.e22 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Phenotype screens of murine pancreatic cancer identify a Tgf-α-Ccl2-paxillin axis driving human-like neural invasion. J. Clin. Invest. 133, e166333 (2023).

Makhmutova, M. & Caicedo, A. Optical imaging of pancreatic innervation. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 663022 (2021).

Schwartz, E. S. et al. TRPV1 and TRPA1 antagonists prevent the transition of acute to chronic inflammation and pain in chronic pancreatitis. J. Neurosci. 33, 5603–5611 (2013).

Ma, Y. et al. Combination of PD-1 inhibitor and OX40 agonist induces tumor rejection and immune memory in mouse models of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 159, 306–319.e12 (2020).

Wang, K. et al. PD-1 blockade inhibits osteoclast formation and murine bone cancer pain. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 3603–3620 (2020).

Wakabayashi, H. et al. Decreased sensory nerve excitation and bone pain associated with mouse Lewis lung cancer in TRPV1-deficient mice. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 36, 274–285 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Chen, M., Liu, Z., Wang, X. & Ji, T. The neuropeptide calcitonin gene-related peptide links perineural invasion with lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 21, 1254 (2021).

Croop, R. et al. Oral rimegepant for preventive treatment of migraine: a phase 2/3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 397, 51–60 (2021).

Lipton, R. B. et al. Rimegepant, an oral calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist, for migraine. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 142–149 (2019).

Shimasaki, N., Jain, A. & Campana, D. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 19, 200–218 (2020).

Dean, I. et al. Rapid functional impairment of natural killer cells following tumor entry limits anti-tumor immunity. Nat. Commun. 15, 683 (2024).