Abstract

In the terrestrial isopod Armadillidium vulgare, many females produce progenies with female-biased sex ratios due to two feminizing sex ratio distorters (SRD): Wolbachia endosymbionts and a nuclear non-mendelian locus called the f element. To investigate the potential impact of these SRD on the evolution of host sex determination, we analyzed their temporal distribution in six A. vulgare populations sampled between 2003 and 2017, for a total of 29 time points. SRD distribution was heterogeneous among populations despite their close geographic locations, so that when one SRD was frequent in a population, the other SRD was rare. In contrast with spatial heterogeneity, our results overall did not reveal substantial temporal variability in SRD prevalence within populations, suggesting equilibria in SRD evolutionary dynamics may have been reached or nearly so. Temporal stability was also generally reflected in mitochondrial and nuclear variation. Nevertheless, in a population, a Wolbachia strain replacement coincided with changes in mitochondrial composition but no change in nuclear composition, thus constituting a typical example of mitochondrial sweep caused by endosymbiont rise in frequency. Rare incongruence between Wolbachia strains and mitochondrial haplotypes suggested the occurrence of intraspecific horizontal transmission, making it a biologically relevant parameter for Wolbachia evolutionary dynamics in A. vulgare. Overall, our results provide an empirical basis for future studies on SRD evolutionary dynamics in the context of multiple sex determination factors co-existing within a single species, to ultimately evaluate the impact of SRD on the evolution of host sex determination mechanisms and sex chromosomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sex ratio distorters (SRD) are selfish genetic elements located on sex chromosomes or transmitted by a single sex, which skew the proportion of males and females in progenies towards the sex that enhances their own vertical transmission (Beukeboom and Perrin 2014). They are found in a wide range of animal and plant species, of which they tremendously impact the ecology and evolution (Burt and Trivers 2006; Werren 2011). SRD are sources of genetic conflicts because they increase their own transmission at the expense of other genetic elements of the genome (Burt and Trivers 2006; Werren 2011; Beukeboom and Perrin 2014). Genetic variants are therefore selected if they mitigate the fitness costs inflicted by SRD. Hence, female-biased sex ratios impose strong selective pressure, known as sex ratio selection, favouring genotypes producing more individuals of the under-represented sex (i.e., males) and ultimately restoring Fisherian (i.e., balanced) sex ratios. Thus, SRD may promote the evolution of host sex determination mechanisms (Burt and Trivers 2006; Werren 2011; Cordaux et al. 2011; Beukeboom and Perrin 2014).

SRD are particularly well documented in arthropods, among which is the emblematic bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia (Werren et al. 2008; Kaur et al. 2021). Wolbachia is a cytoplasmic, maternally inherited alpha-proteobacterium that often acts as a reproductive parasite by manipulating host reproduction in favor of infected females, thereby conferring itself a transmission advantage. In particular, Wolbachia has evolved the ability to induce female-biased sex ratios in host progenies through male killing, thelytokous (i.e., all female-producing) parthenogenesis and feminization (Werren et al. 2008; Cordaux et al. 2011; Hurst and Frost 2015; Kaur et al. 2021).

Feminization, causing infected (and non-transmitting) genetic males to develop into (transmitting) phenotypic females, is mostly documented in terrestrial isopods (Martin et al. 1973). In the well-studied Armadillidium vulgare, chromosomal sex determination follows female heterogamety (ZZ males and ZW females) (Juchault and Legrand 1972; Chebbi et al. 2019; Cordaux et al. 2021). In some A. vulgare populations, sex ratio is biased by Wolbachia bacteria or by a nuclear locus called the f element (Rigaud et al. 1997; Cordaux et al. 2011; Cordaux and Gilbert 2017). Three Wolbachia strains are known to naturally occur in A. vulgare: wVulC, wVulM and wVulP (Rigaud et al. 1991; Cordaux et al. 2004; Verne et al. 2007). The f element results from the horizontal transfer of a large portion of a feminizing Wolbachia genome in the A. vulgare genome (Leclercq et al. 2016). The f element induces female development, as a W chromosome does, and it shows non-Mendelian inheritance, making it an SRD (Legrand and Juchault 1984; Leclercq et al. 2016). In this species, sex ratio selection has resulted in the evolution of a masculinizing allele restoring balanced sex ratios, hence conferring resistance to feminization (Rigaud and Juchault 1993). This nuclear locus represents a new male sex-determining locus, thereby effectively establishing a new male heterogametic system XY/XX. Thus, multiple sex determination factors co-exist in A. vulgare, ultimately caused by feminizing SRD (Juchault and Mocquard 1993; Cordaux and Gilbert 2017). Given the widespread distribution of Wolbachia infection in terrestrial isopods (Bouchon et al. 1998; Cordaux et al. 2012), it has been suggested that SRD may have contributed to the frequent turnovers of sex chromosomes recorded in this clade (Juchault and Mocquard 1993; Juchault and Rigaud 1995; Becking et al. 2017, 2019; Russell et al. 2021).

To elucidate the potential impact of SRD on the evolution of sex determination in terrestrial isopods, it is essential to clarify the intraspecific evolutionary dynamics of SRD such as Wolbachia and the f element. Previous studies have shown that: (i) Wolbachia and the f element are present at variable frequencies in A. vulgare populations, (ii) the f element is overall more frequent than Wolbachia, (iii) the two SRD usually do not co-occur at high frequency in populations, and (iv) mitochondrial haplotypes (mitotypes) are tightly linked to Wolbachia strains (suggesting stable maternal transmission), but not to the f element (Juchault et al. 1993; Durand et al. 2023). These results have provided insights into the spatial distribution of Wolbachia and the f element in A. vulgare; in the present study, we investigate their temporal dynamics.

Prior studies on endosymbiont temporal dynamics have shown that host population invasions can occur within just a few years, e.g., Wolbachia in Drosophila simulans (Turelli and Hoffmann 1991) and Eurema hecabe (Miyata et al. 2024), and Rickettsia in Bemisia tabaci (Himler et al. 2011). Likewise, nuclear suppressors of SRD can rise in frequency very quickly, e.g., Wolbachia suppressor in Hypolimna bolina (Charlat et al. 2007). Similar patterns of rapid spread and evolution of resistance have been reported for a nuclear SRD, Paris Sex Ratio, in D. simulans (Helleu et al. 2019). Endosymbiont temporal dynamics has seldom been studied on a longer time scale. Comparison of historical (i.e., museum) and contemporary sympatric populations of H. bolina highlighted fluctuations of Wolbachia frequency over periods of 73–123 years (Hornett et al. 2009). However, at an intermediate time scale (10–20 years), Wolbachia was found to decrease in frequency in Acraea encedon (Hassan et al. 2013), while it was stably maintained in Eurema mandarina (Kageyama et al. 2020) and D. simulans (Weeks et al. 2007; Carrington et al. 2011). In the case of A. vulgare, SRD temporal dynamics has previously been tackled by a single study (Juchault et al. 1992), in which Wolbachia prevalence was found to decrease concomitantly to an increase of f element prevalence in an A. vulgare population from Niort (western France) sampled at three time points over a period of 23 years (1963, 1973 and 1986). However, a single population was included in the study, thus limiting the breadth of its conclusions. Here we report an analysis of Wolbachia and f element distribution in six A. vulgare populations sampled each up to six times over up to 12 years, representing a total of 889 individuals from 29 time points. The studied populations were sampled in a narrow geographic area in western France, within 70 km of the Niort population (Juchault et al. 1992), to control for spatial dynamics. In contrast to most previous studies, here we analyzed SRD in the context of both mitochondrial and nuclear variation. Our results highlight an overall temporal stability of SRD distribution in A. vulgare, with few exceptions.

Materials and Methods

A total of 889 A. vulgare individuals were analyzed, from six natural populations sampled in western France between 2003 and 2017 (Fig. 1). DNA samples from Beauvoir-2017, Chizé-2017, Coulombiers-2017, Gript-2017, La Crèche-2017 and Poitiers-2015 were available from Durand et al. (2023). All other individuals were collected by hand. Sex ratios in sampled individuals should not be considered as reflecting those of populations, due to possible selection biases by samplers. Individuals were sexed and stored in alcohol or at −20 °C prior to DNA extraction. Total genomic DNA of samples collected between 2003 and 2013 was extracted from gonads using phenol and chloroform (Kocher et al. 1989) and DNA of samples collected between 2014 and 2016 was extracted from the head and legs, as described previously (Leclercq et al. 2016).

Four molecular markers were used to assess the presence of Wolbachia and the f element in DNA extracts: Jtel (Leclercq et al. 2016), wsp (Braig et al. 1998), recR (Badawi et al. 2014) and ftsZ (Werren et al. 1995) (Table S1). While Jtel is specific to the f element, wsp and recR are specific to Wolbachia, and ftsZ is present in both the f element and Wolbachia (Leclercq et al. 2016). The presence or absence of these markers was assessed by PCR assays, as described previously (Leclercq et al. 2016). Different amplification patterns were expected for individuals with Wolbachia only (Jtel-, wsp + , recR + , ftsZ + ), the f element only (Jtel + , wsp-, recR-, ftsZ + ), both Wolbachia and the f element present (Jtel + , wsp + , recR + , ftsZ + ) or both Wolbachia and the f element lacking (Jtel-, wsp-, recR-, ftsZ-). The few individuals exhibiting other amplification patterns were classified as “undetermined status”.

To characterize Wolbachia strain diversity, wsp PCR products were purified and Sanger sequenced using both forward and reverse primers by GenoScreen (Lille, France). Sequences from forward and reverse reads were assembled using Geneious v.7.1.9 to obtain one consensus sequence per individual.

To evaluate mitochondrial diversity, a ~ 700 bp-long portion of the Cytochrome Oxidase I (COI) gene was amplified by PCR in all individuals (Folmer et al. 1994) (Table S1). PCR products were purified and Sanger sequenced as described above. Mitotype networks were built using the pegas package for R (Paradis 2010).

To evaluate nuclear diversity, all individuals were genotyped at 22 microsatellite markers (Verne et al. 2006; Giraud et al. 2013) distributed in five multiplexes (Multiplex 1: Av1, Av2, Av4, Av5, Av9; Multiplex 2: Av6, Av3, Av8; Multiplex 3: AV0023, AV0056, AV0085, AV0086, AV0096; Multiplex 4: AV0002, AV0016, AV0018, AV0032, AV0099; Multiplex 5: AV0061, AV0063, AV0089, AV0128) (Table S2). PCR was performed using fluorescence-marked forward primers, as described previously (Durand et al. 2017). PCR fragments were separated by electrophoresis on an ABI 3730XL automated sequencer by Genoscreen (Lille, France). Alleles were scored using the software GeneMapper 3.7 (Applied Biosystems), each genotype being independently read by two people.

Of the 22 amplified microsatellite markers, Av4 and Av5 could not be scored because of multiple peaks, AV0096 and AV0128 did not amplify consistently, and AV0023 and AV0061 were monomorphic across the dataset. The Genepop package for R (Rousset 2008) detected no linkage disequilibrium between the 16 remaining loci. The presence of null alleles was tested by using a combination of software, as recommended previously (Dąbrowski et al. 2014): Micro-Checker (Van Oosterhout et al. 2004), Cervus (Kalinowski et al. 2007) and ML-NullFreq (Kalinowski and Taper 2006). As a result, AV0099 was discarded because it consistently presented hints of null alleles in many populations and sampling years. Individuals whose genotypes were available for fewer than 13 out of the 15 remaining markers were removed from the following analyses.

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was tested for each locus, locality and sampling year with an exact test using Markov chain with the Genepop package for R. The Fstat software v. 2.9.3.2 (Goudet 2001) was used to calculate allelic richness and heterozygosity (based on a minimum of 3 individuals). Genetic differentiation was estimated by computing Fst values for all pairs of populations (Weir and Cockerham 1984) with Fstat. Significance was calculated using global tests implemented in Fstat with a level of significance adjusted for multiple tests using the standard Bonferroni correction. The longitudes and latitudes of the populations were used to calculate Euclidean distances between populations and to test for isolation by distance by correlating these geographical distances with the genetic distances. Significance of the correlation was tested at individual scale by using a Mantel test (with 9999 permutations) implemented in GENALEX v 6.2 (Peakall and Smouse 2006). Genetic clusters were also delineated without a priori with a Bayesian, individual-based approach implemented in the software Structure (Pritchard et al. 2000). The admixture model was selected, as well as the option of correlated allele frequencies. The number of clusters (K) varied from 2 to 9. For each value of K, 20 independent runs were carried out, as recommended in Evanno et al. (2005), with a total number of 100,000 iterations and a burn-in of 10,000. To determine the most likely value of K, the method described in Evanno et al. (2005) was applied as implemented in Structure Harvester version 0.6.9 (Earl and vonHoldt 2012). In addition, a Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components (DAPC) (Jombart et al. 2010) was performed on populations according to their sampling locality and year with the adegenet package (Jombart 2008), to search for potential discrepancies across time points within populations.

Statistical analyses were carried out using the R software (v.4.2.1). The influence of sex, and population if appropriate, on SRD prevalence was analyzed using general linear models with a binomial error distribution. Maximal models, including all higher order interactions, were simplified by sequentially eliminating non-significant terms and interactions to establish a minimal model (Crawley 2012). The significance of the explanatory variables was established using a likelihood ratio test, which is approximately distributed as a Chi-square distribution (Bolker 2008). The significant Chi-squared values given in the text are for the minimal model, whereas non-significant values correspond to those obtained before the deletion of the variable from the model. Chi-square tests were used to compare the frequency of individuals infected by Wolbachia and the frequency of individuals carrying the f-element in the different populations. Figures were realized with ggplot2 (Wickham et al. 2020). Results from Structure were processed with the program Distruct (Rosenberg 2003) for graphical representation.

Results

We tested the presence of Wolbachia and the f element in 889 individuals (627 females and 262 males) from six populations sampled at various time points between 2003 and 2017, representing a total of 29 sampling points (Tables 1 and S3). Among the 889 analyzed individuals, we failed to determine the status of 29 individuals. Of the remaining 860 individuals, 29.9% carried only the f element, 15.2% carried only Wolbachia, 0.6% carried both SRD and 54.3% carried none. Although sometimes present in males, both SRD were significantly more frequent in females than in males (Wolbachia: χ² = 73.59, p < 0.0001; f element: χ² = 41.03, p < 0.0001, Tables 1 and S3). Wolbachia-infected individuals carried one of the three previously known Wolbachia strains of A. vulgare: wVulC (n = 22), wVulM (n = 25) or wVulP (n = 83).

Overall, both SRD were found at least at one time point in all six populations (Fig. 2). However, the populations displayed substantial variation in the distribution of the two SRD. In Beauvoir, Chizé, Coulombiers and La Crèche populations, the f element was significantly more predominant (29–86% frequency) than Wolbachia (2–10%) (χ² > 36.91 and p < 10−9 in all four populations). Conversely, Wolbachia was significantly more frequent (63%) than the f element (2%) in Poitiers (χ² > 135.32, p < 10−16). Finally, both SRD were very rare in Gript (2–3%) and did not differ in frequencies (χ² = 0.10, p = 0.748). Remarkably, f element prevalence did not differ significantly across time points (spanning up to 12 years) in all four populations in which it was predominant (χ² = 0.002, p = 0.968), although f element prevalence was significantly different among populations (χ² = 62.55, p < 0.0001). In these populations, f element prevalence was significantly higher in females than in males (χ² = 61.87, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). In Poitiers, where Wolbachia remained globally frequent over time, females were also significantly more infected than males (χ² = 106.06, p < 0.0001). Interestingly, the frequency of the wVulC strain significantly decreased over time (χ² = 12.18, p < 0.0001) while the wVulP strain exhibited the opposite trend, and significantly so (χ² = 6.03, p = 0.014).

Sequencing of the COI mitochondrial gene of 884 individuals identified 12 mitotypes, nine of which have previously been detected in A. vulgare populations (named I to VIII, and XII) (Durand et al. 2023) and three are newly described mitotypes (XXIV to XXVI; GenBank accession numbers OR074129 to OR074131, respectively) (Fig. 3 and Table S3). There was an excellent congruence between Wolbachia strains and mitotypes, as previously reported (Verne et al. 2012; Durand et al. 2023). Indeed, individuals carrying wVulC were associated with either mitotype V or its close relatives (XII and XXVI), those carrying wVulP were associated with mitotype VII and those carrying wVulM were associated with mitotype II. Exceptions included two individuals infected by wVulM, which were associated with the distantly related mitotypes I and III. By contrast, the f element was found in eight different mitochondrial backgrounds (I to VI, VIII and XXV) distributed across the mitochondrial network.

Mitochondrial haplotype network of 12 mitochondrial variants from six Armadillidium vulgare populations sampled at different time points. Each circle represents one haplotype and circle diameter is proportional to the number of individuals carrying the haplotype. Branch lengths connecting circles are proportional to divergence between haplotypes.

All time points considered, there were between three (in Chizé) and six (in Poitiers) mitotypes per population (Figs. 3 and S1). Mitotype frequencies were globally stable across time points within populations (e.g., Coulombiers, Fig. 4A), with the notable exceptions of La Crèche and Poitiers populations. In La Crèche, a shift in major mitotypes occurred between 2005 and 2012, with the increasing rarity of mitotype III and V being concomitant with the rise in frequency of mitotypes I and VIII, followed by stability since 2012 (Fig. 4B). In Poitiers, the rise in frequency of mitotype VII (associated with Wolbachia strain wVulP) coincided with a relative decrease of wVulC-associated mitotypes V, XII and XXVI (Fig. 4C).

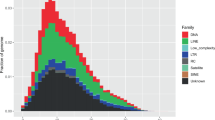

To test if the patterns of SRD and mitochondrial variation were also reflected in the nuclear genome, we examined variation in 667 individuals with genotype information available for at least 13 out of the 15 retained microsatellite markers (see Materials and Methods), representing a total of 28 sampling points (Poitiers-2015 was discarded due to low genotyping success) (Table S3). None of the loci significantly departed from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for all sampling points. Allelic richness ranged from 1 to 4.78 and heterozygosity ranged from 0 to 0.91 (Table S4). Pairwise Fst values ranged from 0 to 0.091 (mean Fst = 0.035) (Table S5). The majority of Fst values between populations (200/321) were significant, suggesting the occurrence of genetic differentiation among populations. Consistently, a Mantel test evaluating the correlation between genetic and geographic distances revealed a significant isolation by distance (r2 = 0.034, p < 0.001). Such a signal of genetic structure was confirmed by Bayesian clustering analyses. Indeed, a delta-K analysis (Evanno et al. 2005) inferred that the best fit to the data was obtained for K = 2 genetic clusters (Fig. S2). A first genetic cluster mainly comprised individuals sampled in Poitiers and Coulombiers, and a second genetic cluster comprised those from Beauvoir, Chizé, La Crèche and Gript (Fig. 5). In agreement with isolation by distance, this clustering pattern reflected the geographic distribution of populations, as the former cluster encompassed eastern-most populations and the latter cluster encompassed western-most populations (Fig. 1). It is noteworthy that the low delta-K values obtained suggested poor convergence between the 20 independent runs, which may be the result of a previously highlighted effect of isolation by distance (Meirmans 2012). By contrast, the clustering analysis did not highlight any obvious change in genetic structure between time points within populations. The DAPC also suggested a major population structuration (Fig. 6), as the first component separated Poitiers and Coulombiers (locating towards the right side of the axis) from the other populations (locating towards the left side of the axis). It also supported overall homogeneity of populations across time points, apart from La Crèche-2005, which was separated from the other La Crèche time points in the second component of the DAPC. The exception of La Crèche-2005 was also reflected in the significant pairwise Fst values between time points within population, which were generally non-significant for the other populations (Table S5).

Assignment of individuals from six A. vulgare populations sampled at different time points to one of two genetic clusters (blue and pink colors) following Bayesian analysis. Each bar represents an individual, and the proportion of each color represents the probability of assignment to the corresponding cluster.

The two axes represent the first two principal components (PC). Dots represent individuals. Each of the 28 sampling points presents a 95% inertia ellipse and is labeled with two letters indicating the population and the two last digits of the sampling year. The eigenvalues of the analysis (inset) show the relative amount of genetic structure captured by the principal components (the first two components are highlighted in dark gray).

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the temporal dynamics of two SRD segregating in natural populations of the terrestrial isopod A. vulgare, to shed light on the potential impact of SRD on the evolution of host sex determination mechanisms at a within-species scale. Wolbachia and f element distributions were highly heterogeneous among populations in our study area, despite their modest geographic distance of at most 80 km. The emerging trend is that when one SRD is frequent in a population, the other SRD is rare, as noted previously (Durand et al. 2023). As it causes a stronger bias toward females, Wolbachia is expected to prevail over the f element in A. vulgare populations (Rigaud 1997; Cordaux and Gilbert 2017). Yet, the f element was the dominant SRD in four out of six populations we studied and was rising in frequency in Niort (Juchault et al. 1992). Overall, the f element is more widespread than Wolbachia in A. vulgare populations (Juchault et al. 1993; Durand et al. 2023). Previously proposed explanations include a higher fitness cost entailed by Wolbachia relative to the f element and occasional paternal transmission of the f element (which some males carry, Fig. 2) enabled by masculinizing epistatic alleles (Juchault et al. 1992; Rigaud and Juchault 1993; Rigaud 1997; Rigaud and Moreau 2004; Cordaux and Gilbert 2017).

In contrast with spatial heterogeneity, our sampling scheme with up to six sampling time points spanning 12 years per population highlights a global temporal stability in SRD prevalence within populations. At first glance, this qualitative pattern differs from that previously reported for the Niort population, in which Wolbachia prevalence was found to decrease concomitantly to an increase of f element prevalence over a period of 23 years (Juchault et al. 1992). Given A. vulgare’s generation time of one year, our study might have spanned too few generations (12) to capture variation in SRD prevalence, which the Niort study spanning 23 generations did. Nevertheless, the time scale of our study enabled us to detect variation in Wolbachia strain prevalence, as well as mitochondrial and nuclear variation within and between populations, suggesting that lack of resolution is not an issue. Alternatively, most of the populations we studied may reflect some relatively stable equilibrium with respect to SRD evolutionary dynamics, an equilibrium that the Niort population might not have reached. Indeed, theoretical models have indicated that when feminizing factors are in competition, the one that induces the strongest bias toward females is expected to spread in the population (Taylor 1990). Thus, a single SRD should remain in the population at equilibrium. Consistently, in most of the populations we analyzed, a single SRD occurs at high frequency, suggesting that these populations may be at or near equilibrium for an SRD. This signal of temporal stability is reminiscent of that recorded in the butterfly E. mandarina, in which the feminizing wFem Wolbachia strain has been stably maintained at high frequency for 12 years in a Japanese population (Kageyama et al. 2020). Similarly, the cytoplasmic incompatibility-inducing wRi Wolbachia strain has apparently reached an equilibrium frequency at ~93% in D. simulans populations from California (Weeks et al. 2007; Carrington et al. 2011). It has been suggested that an apparent stability could be due to hidden processes such as population structure (including extinction-recolonization processes), intragenomic conflicts and coevolutionary processes (Hatcher 2000).

The temporal stability of SRD in most of A. vulgare populations is also reflected in host mitochondrial and nuclear variation, with two notable exceptions. The first one is La Crèche population in 2005, which differs from the other time points (2012 to 2017) on both mitochondrial and nuclear grounds. Interestingly, the sampling spot in La Crèche has been altered by land remodeling between 2005 and 2012. This anthropogenic activity may have caused the reduction or collapse of the historic A. vulgare population and the introduction of new individuals as part of the addition of materials during the remodeling (e.g., soil from another location). Such an extinction-recolonization scenario may explain the loss of Wolbachia (present at low frequency in 2005) and the increase in f element frequency in 2012. It is noteworthy that from 2012 on, SRD, mitochondrial and nuclear variation have been stable, suggesting that stabilization of the population dynamics may be reached in a few years.

The second case of instability is the Poitiers population, which is stable with respect to nuclear variation but not to both mitochondrial and SRD variation. Poitiers is the only population in our dataset in which Wolbachia is the dominant SRD across time points, thus highlighting a qualitative pattern of temporal stability. However, our results indicate that the rise in frequency of the wVulP strain correlates with a decrease of the wVulC strain, suggesting a Wolbachia strain replacement in this population. The wVulP strain is characterized by a recombination event involving wVulC (Verne et al. 2007), indicating that wVulC is older than wVulP, which is consistent with the situation recorded in Poitiers. Assuming the driver of this replacement is Wolbachia and not another cytoplasmic element (like the mitochondrion), replacement of wVulC by wVulP could be due to the latter strain having a transmission advantage over the former strain. Unfortunately, the wVulP strain is not very well characterized, and while feminization induction is likely (Verne et al. 2007), it has not been formally demonstrated and compared to feminization induced by wVulC (Rigaud et al. 1991; Cordaux et al. 2004). Neither has the respective costs of these two Wolbachia strains been investigated. In any event, because Wolbachia and mitochondria are co-inherited cytoplasmic entities, changes in Wolbachia strains associated with different mitotypes are expected to lead to concomitant changes in mitochondrial variation, but no change in nuclear variation. Therefore, our observations in Poitiers may constitute a typical example of mitochondrial sweep caused by endosymbiont rise in frequency (Galtier et al. 2009).

Wolbachia dynamics in Poitiers also illustrates that transovarial, maternal transmission is the main transmission mode of Wolbachia in A. vulgare. However, non-maternal transmission may also occur, as suggested by two individuals with wVulM from Beauvoir and La Crèche. These individuals carry mitotypes I and III, respectively, unlike all other wVulM-infected individuals which carry mitotype II. As mitotypes I, II and III are distantly related, a plausible explanation is that the two unusual individuals have acquired Wolbachia by horizontal transfer, although the hypothesis of historical infections cannot be formally discarded. Horizontal transfer of Wolbachia is largely documented in arthropods (O’Neill et al. 1992; Werren et al. 1995; Heath et al. 1999; Vavre et al. 1999), including terrestrial isopods (Bouchon et al. 1998; Cordaux et al. 2001, 2012). Potential mechanisms in isopods include contact between wounded individuals (Rigaud and Juchault 1995) and cannibalism/predation (Le Clec’h et al. 2013). In total, our results suggest that two out of 136 Wolbachia-infected individuals could conceivably have acquired their symbionts by horizontal transmission. This may be an underestimate, as horizontal transfers between individuals carrying the same mitotype cannot be detected with our approach. If so, horizontal transmission may occur at a measurable rate in A. vulgare, suggesting that it is a parameter of importance in Wolbachia evolutionary dynamics in this species.

To conclude, the evolutionary dynamics of SRD, mitochondrial and nuclear variation from various populations over a period of up to 12 years revealed that distributions of Wolbachia and the f element were much more variable spatially than temporally. This conclusion is well supported for the f element, with four populations independently showing the same pattern. For Wolbachia, it has remained at high frequency over time but strain genotyping identified an apparently ongoing strain replacement. It is however more difficult to draw strong conclusions for this SRD as it occurred at high frequency in a single population. Such geographic and temporal distribution suggests that migration may not heavily influence SRD evolution in A. vulgare, a species exhibiting strong female phylopatry (Durand et al. 2019). This is in contrast with the highly dispersive H. bolina, in which Wolbachia frequency has been shown to fluctuate over time (Hornett et al. 2009). Overall, our results provide an empirical basis for future studies on SRD evolutionary dynamics in the context of multiple sex determination factors co-existing within a single species, such as modeling investigations. These efforts will ultimately contribute to assess the impact of SRD on the evolution of host sex determination mechanisms and sex chromosomes.

Data availability

Mitotypes are available in GenBank under accession numbers OR074129 to OR074131. All other data are provided in the supplementary information.

References

Badawi M, Giraud I, Vavre F, Grève P, Cordaux R (2014) Signs of neutralization in a redundant gene involved in homologous recombination in Wolbachia endosymbionts. Genome Biol Evol 6:2654–2664

Becking T, Chebbi MA, Giraud I, Moumen B, Laverré T, Caubet Y et al. (2019) Sex chromosomes control vertical transmission of feminizing Wolbachia symbionts in an isopod. PLOS Biol 17:e3000438

Becking T, Giraud I, Raimond M, Moumen B, Chandler C, Cordaux R et al. (2017) Diversity and evolution of sex determination systems in terrestrial isopods. Sci Rep 7:1–14

Beukeboom LW, Perrin N (2014) The evolution of sex determination. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bolker BM (2008) Ecological models and data in R. Princeton University Press: Princeton and Oxford.

Bouchon D, Rigaud T, Juchault P (1998) Evidence for widespread Wolbachia infection in isopod crustaceans: molecular identification and host feminization. Proc Biol Sci 265:1081–1090

Braig HR, Zhou WG, Dobson SL, O’Neill SL (1998) Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding the major surface protein of the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. J Bacteriol 180:2373–2378

Burt A, Trivers R (2006) Genes in conflict. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Carrington LB, Lipkowitz JR, Hoffmann AA, Turelli M (2011) A re-examination of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in California Drosophila simulans. PloS One 6:e22565

Charlat S, Hornett EA, Fullard JH, Davies N, Roderick GK, Wedell N et al. (2007) Extraordinary flux in sex ratio. Science 317:214

Chebbi MA, Becking T, Moumen B, Giraud I, Gilbert C, Peccoud J et al. (2019) The genome of armadillidium vulgare (Crustacea, Isopoda) provides insights into sex chromosome evolution in the context of cytoplasmic sex determination. Mol Biol Evol 36:727–741

Cordaux R, Bouchon D, Greve P (2011) The impact of endosymbionts on the evolution of host sex-determination mechanisms. Trends Genet 27:332–341

Cordaux R, Chebbi MA, Giraud I, Pleydell DRJ, Peccoud J (2021) Characterization of a sex-determining region and its genomic context via statistical estimates of haplotype frequencies in daughters and sons sequenced in pools. Genome Biol Evol 13:evab121

Cordaux R, Gilbert C (2017) Evolutionary significance of wolbachia-to-animal horizontal gene transfer: female sex determination and the f element in the isopod armadillidium vulgare. Genes 8:186

Cordaux R, Michel Salzat A, Bouchon D (2001) Wolbachia infection in crustaceans: novel hosts and potential routes for horizontal transmission. J Evol Biol 14:237–243

Cordaux R, Michel-Salzat A, Frelon-Raimond M, Rigaud T, Bouchon D (2004) Evidence for a new feminizing Wolbachia strain in the isopod Armadillidium vulgare: evolutionary implications. Heredity 93:78–84

Cordaux R, Pichon S, Hatira HB, Doublet V, Greve P, Marcade I et al. (2012) Widespread Wolbachia infection in terrestrial isopods and other crustaceans. Zookeys 176:123–131

Crawley MJ (2012) The R book. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester.

Dąbrowski MJ, Pilot M, Kruczyk M, Żmihorski M, Umer HM, Gliwicz J (2014) Reliability assessment of null allele detection: inconsistencies between and within different methods. Mol Ecol Resour 14:361–373

Durand S, Cohas A, Braquart-Varnier C, Beltran-Bech S (2017) Paternity success depends on male genetic characteristics in the terrestrial isopod Armadillidium vulgare. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 71:90

Durand S, Grandjean F, Giraud I, Cordaux R, Beltran-Bech S, Bech N (2019) Fine-scale population structure analysis in Armadillidium vulgare (Isopoda: Oniscidea) reveals strong female philopatry. Acta Oecol 101

Durand S, Lheraud B, Giraud I, Bech N, Grandjean F, Rigaud T et al. (2023) Heterogeneous distribution of sex ratio distorters in natural populations of the isopod Armadillidium vulgare. Biol Lett 19:20220457

Earl DA, vonHoldt BM (2012) STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour 4:359–361

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J (2005) Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: a simulation study. Mol Ecol 14:2611–2620

Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R (1994) DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol 3:294–299

Galtier N, Nabholz B, Glémin S, Hurst GDD (2009) Mitochondrial DNA as a marker of molecular diversity: a reappraisal. Mol Ecol 18:4541–4550

Giraud I, Valette V, Bech N, Grandjean F, Cordaux R (2013) Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci for the isopod crustacean Armadillidium vulgare and transferability in terrestrial isopods. Plos One 8:e76639

Goudet (2001) FSTAT, a program to estimate and test gene diversities and fixation indices, version 2.9.3. http://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.htm

Hassan SSM, Idris E, Majerus MEN (2013) Male-killer dynamics in the tropical butterfly acraea encedon (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). Afr Entomol 21:209–214

Hatcher MJ (2000) Persistence of selfish genetic elements: population structure and conflict. Trends Ecol Evol 15:271–277

Heath BD, Butcher RDJ, Whitfield WGF, Hubbard SF (1999) Horizontal transfer of Wolbachia between phylogenetically distant insect species by a naturally occurring mechanism. Curr Biol 9:313–316

Helleu Q, Courret C, Ogereau D, Burnham KL, Chaminade N, Chakir M et al. (2019) Sex-ratio meiotic drive shapes the evolution of the Y chromosome in drosophila simulans. Mol Biol Evol 36:2668–2681

Himler AG, Adachi-Hagimori T, Bergen JE, Kozuch A, Kelly SE, Tabashnik BE et al. (2011) Rapid spread of a bacterial symbiont in an invasive whitefly is driven by fitness benefits and female bias. Science 332:254–256

Hornett EA, Charlat S, Wedell N, Jiggins CD, Hurst GDD (2009) Rapidly shifting sex ratio across a species range. Curr Biol CB 19:1628–1631

Hurst GDD, Frost CL (2015) Reproductive parasitism: maternally inherited symbionts in a biparental world. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7:a017699

Jombart T (2008) adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24:1403–1405

Jombart T, Devillard S, Balloux F (2010) Discriminant analysis of principal components: a new method for the analysis of genetically structured populations. BMC Genet 11:94

Juchault P, Legrand JJ (1972) Croisement de néo-mâles experimentaux chez Armadillidium vulgare Latr. (Crustace, Isopode, Oniscoide). Mise en evidence d’une hétérogamétie femelle. C R Acad Sci Paris 274:1387–1389

Juchault P, Mocquard JP (1993) Transfer of a parasitic sex factor to the nuclear genome of the host: A hypothesis on the evolution of sex-determining mechanisms in the terrestrial isopod Armadillidium vulgare Latr. J Evol Biol 6:511–528

Juchault P, Rigaud T (1995) Evidence for female heterogamety in two terrestrial crustaceans and the problem of sex chromosome evolution in isopods. Heredity 75:466–471

Juchault P, Rigaud T, Mocquard J-P (1992) Evolution of sex-determining mechanisms in a wild population of Armadillidium vulgare Latr. (Crustacea, Isopod): competition between two feminizing parasitic sex factors. Heredity 69:382–390

Juchault P, Rigaud T, Mocquard J-P (1993) Evolution of sex determination and sex ratio variability in wild populations of Armadillidium vulgare (Latr.) (Crustacea, Isopoda): a case study in conflict resolution. Acta Oecologica 14:547–562

Kageyama D, Narita S, Konagaya T, Miyata MN, Abe J, Mitsuhashi W, et al. (2020) Persistence of a Wolbachia-driven sex ratio bias in an island population of Eurema butterflies. 2020.03.24.005017

Kalinowski ST, Taper ML (2006) Maximum likelihood estimation of the frequency of null alleles at microsatellite loci. Conserv Genet 7:991–995

Kalinowski ST, Taper ML, Marshall TC (2007) Revising how the computer program cervus accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Mol Ecol 16:1099–1106

Kaur R, Shropshire JD, Cross KL, Leigh B, Mansueto AJ, Stewart V et al. (2021) Living in the endosymbiotic world of Wolbachia: a centennial review. Cell Host Microbe 29:879–893

Kocher TD, Thomas WK, Meyer A, Edwards SV, Paabo S, Villablanca FX et al. (1989) Dynamics of mitochondrial-DNA evolution in animals: amplification and sequencing with conserved primers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:6196–6200

Le Clec’h W, Chevalier FD, Genty L, Bertaux J, Bouchon D, Sicard M (2013) Cannibalism and predation as paths for horizontal passage of Wolbachia between terrestrial isopods. PLoS One 8:e60232

Leclercq SB, Thézé J, Chebbi MA, Giraud I, Moumen B, Ernenwein L et al. (2016) Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:15036–15041

Legrand JJ, Juchault P (1984) Nouvelles données sur le déterminisme génétique et épigénétique de la monogénie chez le crustacés isopodes terrestres Armadillidium vulgare Latr. Génét Sél Evol 16:57–84

Martin G, Juchault P, Legrand JJ (1973) Mise en évidence d’un micro-organisme intracytoplasmique symbiote de l’Oniscoide Armadillidium vulgare L. dont la présence accompagne l’intersexualité ou la féminisation totale des mâles génétiques de la lignée thélygène. Comptes Rendus Académie Sci Paris 276:2313–2316

Meirmans PG (2012) The trouble with isolation by distance. Mol Ecol 21:2839–2846

Miyata M, Nomura M, Kageyama D (2024) Rapid spread of a vertically transmitted symbiont induces drastic shifts in butterfly sex ratio. Curr Biol 34:R490–R492

O’Neill SL, Giordano R, Colbert AM, Karr TL, Robertson HM (1992) 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial endosymbionts associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:2699–2702

Paradis E (2010) pegas: an R package for population genetics with an integrated–modular approach. Bioinformatics 26:419–420

Peakall R, Smouse PE (2006) genalex 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Popul Genet Softw Teach Res Mol Ecol Notes 6:288–295

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155:945

Rigaud T (1997) Inherited microorganisms and sex determination of arthropod hosts. In: O’Neill SL, Hoffmann AA, Werren JH (eds) Influential passengers: inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction, Oxford Univ. Press: Oxford, pp 81–101

Rigaud T, Juchault P (1993) Conflict between feminizing sex ratio distorters and an autosomal masculinizing gene in the terrestrial isopod Armadillidium vulgare Latr. Genetics 133:247–252

Rigaud T, Juchault P (1995) Success and failure of horizontal transfers of feminizing Wolbachia endosymbionts in woodlice. J Evol Biol 8:249–255

Rigaud T, Juchault P, Mocquard JP (1997) The evolution of sex determination in isopods crustaceans. Bioessays 19:409–416

Rigaud T, Moreau M (2004) A cost of Wolbachia-induced sex reversal and female-biased sex ratios: decrease in female fertility after sperm depletion in a terrestrial isopod. Proc R Soc B-Biol Sci 271:1941–1946

Rigaud T, Souty Grosset C, Raimond R, Mocquard JP, Juchault P (1991) Feminizing endocytobiosis in the terrestrial crustacean Armadillidium vulgare Latr. (Isopoda): recent acquisitions. Endocytobiosis Cell Res 7:259–273

Rosenberg NA (2003) DISTRUCT: a program for the graphical display of population structure. Mol Ecol Notes 4:137–138

Rousset F (2008) GENEPOP’007: a complete re-implementation of the GENEPOP software for Windows and Linux. Mol Ecol Resour 8:103–106

Russell A, Borrelli S, Fontana R, Laricchiuta J, Pascar J, Becking T et al. (2021) Evolutionary transition to XY sex chromosomes associated with Y-linked duplication of a male hormone gene in a terrestrial isopod. Heredity 127:266–277

Taylor DR (1990) Evolutionary consequences of cytoplasmic sex ratio distorters. Evol Ecol 4:235–248

Turelli M, Hoffmann AA (1991) Rapid spread of an inherited incompatibility factor in California Drosophila. Nature 353:440–442

Van Oosterhout C, Hutchinson WF, Wills DPM, Shipley P (2004) Micro-checker: software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol Ecol Notes 4:535–538

Vavre F, Fleury F, Lepetit D, Fouillet P, Boulétreau M (1999) Phylogenetic evidence for horizontal transmission of Wolbachia in host-parasitoid associations. Mol Biol Evol 16:1711–1723

Verne S, Johnson M, Bouchon D, Grandjean F (2007) Evidence for recombination between feminizing Wolbachia in the isopod genus Armadillidium. Gene 397:58–66

Verne S, Johnson M, Bouchon D, Grandjean F (2012) Effects of parasitic sex-ratio distorters on host genetic structure in the Armadillidium vulgare-Wolbachia association. J Evol Biol 25:264–276

Verne S, Puillandre N, Brunet G, Gouin N, Samollow PB, Anderson JD et al. (2006) Characterization of polymorphic microsatellite loci in the terrestrial isopod Armadillidium vulgare. Mol Ecol Notes 6:328–330

Weeks AR, Turelli M, Harcombe WR, Reynolds KT, Hoffmann AA (2007) From parasite to mutualist: rapid evolution of Wolbachia in natural populations of Drosophila. PLoS Biol 5:e114

Weir BS, Cockerham CC (1984) Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38:1358–1370

Werren JH (2011) Selfish genetic elements, genetic conflict, and evolutionary innovation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(2):10863–10870

Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME (2008) Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:741–751

Werren JH, Zhang W, Guo LR (1995) Evolution and phylogeny of Wolbachia: reproductive parasites of arthropods. Proc Biol Sci 261:55–63

Wickham H, Chang W, Henry L, Pedersen TL, Takahashi K, Wilke C, et al. (2020) ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/index.html

Acknowledgements

We thank Sébastien Verne and Victorien Valette for assistance with sample collection. This work was funded by Agence Nationale de la Recherche Grants ANR-15-CE32-0006 (CytoSexDet) to RC and TR, and ANR-20-CE02-0004 (SymChroSex) to JP, and intramural funds from the CNRS and the University of Poitiers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RC, JP and TR designed the experiments. FG, NB and JP sampled populations. SD, IG and AL performed laboratory work. SD, RP and NB performed data analyses. RC and SD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TR, JP, NB, RP and FG amended the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

No specific permission was required for sampling the populations from Beauvoir, Chizé, Gript and La Crèche because they were located in public areas. Populations from Coulombiers and Poitiers were sampled on private lands after the land owners gave permission to conduct sampling on the sites.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Associate editor: Louise Johnson

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Durand, S., Pigeault, R., Giraud, I. et al. Temporal stability of sex ratio distorter prevalence in natural populations of the isopod Armadillidium vulgare. Heredity 133, 287–297 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-024-00713-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-024-00713-1