Abstract

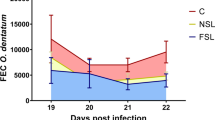

Diet is one of the strongest ecological forces shaping the gut environment, yet its impact on intestinal worms (helminths) remains poorly understood. The helminth Hymenolepis diminuta is a suitable model for investigating how lifestyle changes in modern societies may disrupt host–helminth relationships. Here we show that dietary fiber availability shapes the developmental trajectory and life strategies of H. diminuta in a stage-dependent manner. Fiber deprivation at the time of host colonization leads to developmental arrest, manifested by reduced growth, absence of reproduction, and transcriptional changes consistent with suppressed development. This state is accompanied by diet-dependent remodeling of the host small intestinal microbiota and metabolome: whereas fiber-rich diets support fermentative microbial communities and a chemically diverse intestinal environment, the Western diet promotes dysbiotic profiles with reduced fermentation capacity and a more pro-inflammatory immune response. In contrast, adult H. diminuta that reach maturity in hosts maintained on a fiber-rich diet exhibit a reversible, estivation-like suppression of reproduction during short-term fiber deprivation, with full restoration of egg production following dietary recovery. Together, these findings indicate that dietary transitions associated with industrialized lifestyles can redirect helminth developmental programs and host–helminth–microbiome interactions, with implications for helminth persistence and potential therapeutic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Transcriptomic data generated in this study are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession code PRJNA1126432. Bacteriome sequencing data are archived in the European Nucleotide Archive under accession code PRJEB86956. Metabolomics data and additional source data supporting the findings of this study—including images and videos of Hymenolepis diminuta, worm length measurements, egg counts, cytokine relative and Cp values, raw and relative body weight data, a checklist of bacteriome sequences, and a table of metabolite annotations and standards are available in the Figshare repository under accession https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26038633. Detailed methodological protocols are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Fan, Y. & Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 55–71 (2021).

Garcia-Bonete, M. J., Rajan, A., Suriano, F. & Layunta, E. The underrated gut microbiota helminths, bacteriophages, fungi, and archaea. Life 13, 1765 (2023).

Lukeš, J., Stensvold, C. R., Jirků-Pomajbíková, K. & Wegener Parfrey, L. Are human intestinal eukaryotes beneficial or commensals? PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005039 (2015).

Chibani, C. M. et al. A catalogue of 1,167 genomes from the human gut archaeome. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 48–61 (2022).

Sobotková, K. et al. Helminth therapy – from the parasite perspective. Trends Parasitol. 35, 501–515 (2019).

Han, G. & Vaishnava, S. Microbial underdogs: exploring the significance of low-abundance commensals in host-microbe interactions. Exp. Mol. Med 55, 2498–2507 (2023).

Rook, G., Bäckhed, F., Levin, B. R., McFall-Ngai, M. J. & McLean, A. R. Evolution, human-microbe interactions, and life history plasticity. Lancet 390, 521–530 (2017).

Reynolds, L. A., Finlay, B. B. & Maizels, R. M. Cohabitation in the intestine: Interactions among helminth parasites, bacterial microbiota, and host immunity. J. Immunol. 195, 4059–4066 (2015).

Jirků, M. et al. Helminth interactions with bacteria in the host gut are essential for its immunomodulatory effect. Microorganisms 9, 226 (2021).

Williams, A. R. et al. Emerging interactions between diet, gastrointestinal helminth infection, and the gut microbiota in livestock. BMC Vet. Res. 17, 62 (2021).

Wammes, L. J. et al. Community deworming alleviates geohelminth-induced immune hyporesponsiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 12526–12531 (2016).

Weinstock, J. V. The worm returns. Nature 491, 183–185 (2012).

Venkatakrishnan, A. et al. Evolution of bacteria in the human gut in response to changing environments: an invisible player in the game of health. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 752–758 (2021).

You, C., Jirků, M., Corcoran, D. L., Parker, W. & Jirků-Pomajbíková, K. Altered gut ecosystems plus the microbiota’s potential for rapid evolution: A recipe for inevitable change with unknown consequences. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 5969–5977 (2021).

Myhill, L. J. et al. Mucosal barrier and Th2 immune responses are enhanced by dietary inulin in pigs infected with Trichuris suis. Front. Immunol. 9, 2557 (2018).

Myhill, L. J. et al. Fermentable dietary fiber promotes helminth infection and exacerbates host inflammatory responses. J. Immunol. 204, 3042–3055 (2020).

Carvalho, N., das Neves, J. H., Pennacchi, C. S. & Amarante, A. F. T. D. Hypobiosis and development of Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus colubriformis infection in lambs under different levels of nutrition. Ruminants 3, 401–412 (2023).

Daniel, H. Gut physiology meets microbiome science. Gut Microbiome 4, 1–14 (2023).

Weiss, A. S. et al. Nutritional and host environments determine community ecology and keystone species in a synthetic gut bacterial community. Nat. Commun. 14, 4780 (2023).

Loke, P. & Harris, N. L. Networking between helminths, microbes, and mammals. Cell Host Microbe 31, 464–471 (2023).

Sulima-Celińska, A., Kalinowska, A. & Młocicki, D. The tapeworm Hymenolepis diminuta as an important model organism in the experimental parasitology of the 21st Century. Pathogens 11, 1439 (2022).

Reyes, J. L. et al. Macrophages treated with antigen from the tapeworm Hymenolepis diminuta condition CD25+ T cells to suppress colitis. FASEB J. 33, 5676–5689 (2019).

Pomajbíková, K. J. et al. The benign helminth Hymenolepis diminuta ameliorates chemically induced colitis in a rat model system. Parasitology 145, 1324–1335 (2018).

Williamson, L. L. et al. Got worms? Perinatal exposure to helminths prevents persistent immune sensitization and cognitive dysfunction induced by early-life infection. Brain Behav. Immun. 51, 14–28 (2016).

McKenney, E. A. et al. Alteration of the rat cecal microbiome during colonization with the helminth Hymenolepis diminuta. Gut Microbes 6, 182–193 (2015).

Parfrey, L. W. et al. A benign helminth alters the host immune system and the gut microbiota in a rat model system. PLoS ONE 12, e0182205 (2017).

Shute, A. et al. Worm expulsion is independent of alterations in the composition of the colonic bacteria that occur during experimental Hymenolepis diminuta infection in mice. Gut Microbes 11, 497–510 (2020).

Cheng, A. M., Jaint, D., Thomas, S., Wilson, J. K. & Parker, W. Overcoming evolutionary mismatch by self-treatment with helminths: current practices and experience. J. Evol. Med 3, 235910 (2015).

Liu, J., Morey, R. A., Wilson, J. K. & Parker, W. Practices and outcomes of self-treatment with helminths based on physicians’ observations. J. Helminthol. 91, 267–277 (2017).

Mettrick, D. F. The intestine as an environment for Hymenolepis diminuta. In Biology of the tapeworm Hymenolepis diminuta (ed. Arai, H. P.) 281–356 (Academic Press Inc., New York, 1980).

Jiang, C., Storey, K. B., Yang, H. & Sun, L. Aestivation in nature: physiological strategies and evolutionary adaptations in hypometabolic states. Int J. Mol. Sci. 24, 14093 (2023).

Hand, S. C., Denlinger, D. L., Podrabsky, J. E. & Roy, R. Mechanisms of animal diapause: recent developments from nematodes, crustaceans, insects, and fish. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 310, 172 (2016).

Diniz, D. F. A., De Albuquerque, C. M. R., Oliva, L. O., De Melo-Santos, M. A. V. & Ayres, C. F. J. Diapause and quiescence: dormancy mechanisms that contribute to the geographical expansion of mosquitoes and their evolutionary success. Parasit. Vectors 10, 310 (2017).

Yang, Q. et al. Transcriptome and metabolome analyses of sea cucumbers Apostichopus japonicus in Southern China during the summer aestivation period. J. Ocean Univ. China 20, 198–212 (2021).

Makino, M., Ulzii, E., Shirasaki, R., Kim, J. & You, Y. J. Regulation of satiety quiescence by neuropeptide signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Front Neurosci. 15, 678590 (2021).

Schmeisser, K. et al. Mobilization of cholesterol induces the transition from quiescence to growth in Caenorhabditis elegans through steroid hormone and mTOR signaling. Commun. Biol. 7, 121 (2024).

Komuniecki, R. & Roberts, L. S. Developmental physiology of cestodes. XIV. Roughage and carbohydrate content of host diet for optimal growth and development of Hymenolepis diminuta. J. Parasitol. 61, 427–433 (1975).

Mettrick, D. F. Competition for ingested nutrients between the tapeworm Hymenolepis diminuta and the rat host. Can. J. Public Health 64, 70–82 (1973).

Herz, M. et al. Genome-wide transcriptome analysis of Echinococcus multilocularis larvae and germinative cell cultures reveals genes involved in parasite stem cell function. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1335946 (2024).

Patel, B. et al. Voltage-gated proton channels modulate mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production by complex I in renal medullary thick ascending limb. Redox Biol. 27, 101191 (2019).

Kawai, T. et al. Regulation of hepatic oxidative stress by voltage-gated proton channels (Hv1/VSOP) in Kupffer cells and its potential relationship with glucose metabolism. FASEB J. 34, 15805–15821 (2020).

Chaidee, A. et al. Transcriptome changes of liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini in diabetic hamsters. Parasite 31, 54 (2024).

Folz, J. et al. Human metabolome variation along the upper intestinal tract. Nat. Metab. 5, 777–788 (2023).

Makki, K., Deehan, E. C., Walter, J. & Bäckhed, F. The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 23, 705–715 (2018).

Kaakoush, N. O. Insights into the role of Erysipelotrichaceae in the human host. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 5, 84 (2015).

Lynch, J. B. et al. Gut microbiota Turicibacter strains differentially modify bile acids and host lipids. Nat. Commun. 14, 3669 (2023).

Beisner, J., Gonzalez-Granda, A., Basrai, M., Damms-Machado, A. & Bischoff, S. C. Fructose-induced intestinal microbiota shift following two types of short-term high-fructose dietary phases. Nutrients 12, 3444 (2020).

Montrose, D. C. et al. Dietary fructose alters the composition, localization, and metabolism of gut microbiota in association with worsening colitis. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 525–550 (2021).

Desai, M. S. et al. A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell 167, 1339–1353 (2016).

Lloyd-Price, J. et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 569, 655–662 (2019).

Cani, P. D. Human gut microbiome: hopes, threats and promises. Gut 67, 1716–1725 (2018).

Louis, P., Solvang, M., Duncan, S. H., Walker, A. W. & Mukhopadhya, I. Dietary fibre complexity and its influence on functional groups of the human gut microbiota. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 80, 386–397 (2021).

Morrison, K. E., Jašarević, E., Howard, C. D. & Bale, T. L. It’s the fiber, not the fat: significant effects of dietary challenge on the gut microbiome. Microbiome 8, 15 (2020).

Meyer, R. K., Bime, M. A. & Duca, F. A. Small intestinal metabolomics analysis reveals differentially regulated metabolite profiles in obese rats and with prebiotic supplementation. Metabolomics 18, 60 (2022).

Davidson, R. E., Leese, H. J. & Davidson, R. E. Sucrose absorption by the rat small intestine in vivo and in vitro. J. Physiol. 267, 237–248 (1977).

Dunkleyl, L. C., Mettrick, D. F. & Dunkley, L. C. A. Hymenolepis diminuta: Effect of quality of host dietary carbohydrate on growth. Exp. Parasitol. 25, 146–161 (1969).

Roberts, L. S. & Platzer, E. G. Developmental physiology of cestodes. II. Effects of changes in host dietary carbohydrate and roughage on previously established Hymenolepis diminuta. J. Parasitol. 53, 85–93 (1967).

Vacca, F. & Le Gros, G. Tissue-specific immunity in helminth infections. Mucosal Immunol. 15, 1212–1223 (2022).

Queiroz-Glauss, C. P. et al. Helminth infection modulates the number and function of adipose tissue Tregs in high-fat diet-induced obesity. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e0010105 (2022).

Su, C. Wen et al. Helminth infection protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity via induction of alternatively activated macrophages. Sci. Rep. 8, 4607 (2018).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. FeatureCounts: an efficient general-purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

Ge, S. X., Son, E. W. & Yao, R. iDEP: an integrated web application for differential expression and pathway analysis of RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinforma. 19, 534 (2018).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e1 (2013).

Pafčo, B. et al. Metabarcoding analysis of strongylid nematode diversity in two sympatric primate species. Sci. Rep. 8, 5933 (2018).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naïve Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261–5267 (2007).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 5261–5267 (2013).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Waste not, want not: why rarefying microbiome data is inadmissible. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10, e1003531 (2014).

Hancock, J. M. Jaccard distance (Jaccard Index, Jaccard Similarity Coefficient). In: Dictionary of bioinformatics and computational biology (eds. Grant, P. & Mandal, S. S.) (John Wiley & Sons, 2004).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, 860 (2011).

Moos, M. et al. Cryoprotective metabolites are sourced from both external diet and internal macromolecular reserves during metabolic reprogramming for freeze tolerance in the Drosophilid fly, Chymomyza costata. Metabolites 12, 163 (2022).

Pfaffl, M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acid Res. 29, e45 (2001).

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under the INTER-EXCELLENCE program (grant no. LTAUSA19008 to K.J.), by the Research Council of Norway (grant no. 324516 to K.J. and M.K.), by the ERD fund project Center for Research of Pathogenicity and Virulence of Parasites (project no. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000759 to M.K., M.O., J.L.), and by the Czech Science Foundation (grant no. 23-07990S to R.K. and 25-15298S to J.L.). We acknowledge the CF Genomics CEITEC MU, provided through the NCMG research infrastructure (LM2023067 funded by MEYS CR), for their support with obtaining scientific data presented in this paper. Computational resources were provided by the e-INFRA CZ project (ID: 90254), supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic and IT4Innovations National Super Computer Center (project #Open-34-44), Technical University of Ostrava, Czech Republic. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and guidance during the review process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J. conceptualized the study, developed methodology, conducted software analyses, performed investigation, carried out formal analysis and data curation, contributed to writing, produced visualizations, validated results, and supervised the work. W.P. contributed to conceptualization and methodology, performed software analyses and investigation, carried out formal analysis and data curation, contributed to writing, produced visualizations, validated results, and supervised the work. O.K. contributed to methodology, software, investigation, visualization, validation, and supervision. M.K. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, formal analysis, and data curation, contributed to writing, produced visualizations, validated results, and supervised the work. V.I. contributed to methodology, software, investigation, visualization, validation, and supervision. M.M.W. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, data curation, writing, visualization, validation, and supervision. R.K. contributed to methodology, software, investigation, visualization, validation, and supervision. M.Mo. contributed to methodology, software, investigation, visualization, validation, and supervision. P.T. contributed to methodology, software, investigation, visualization, validation, and supervision. A.T. contributed to methodology, software, investigation, visualization, validation, and supervision. Z.P. contributed to methodology, software, investigation, visualization, validation, and supervision. K.B. contributed to methodology, software, investigation, visualization, validation, and supervision. J.L. performed formal analysis and contributed to writing. M.O. contributed to conceptualization, software, formal analysis, data curation, writing, visualization, validation, and supervision. B.P. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, data curation, writing, visualization, validation, and supervision. K.J. conceptualized the study, developed methodology, performed software analyses and investigation, carried out formal analysis and data curation, contributed to writing, produced visualizations, validated results, and supervised the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Coauthor W.P. has licensed intellectual property related to helminth therapy, which is owned by Duke University. This intellectual property is unrelated to the experimental design, data generation, analysis, or interpretation of the results presented in this study. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jirků, M., Parker, W., Kadlecová, O. et al. Developmental plasticity enables an intestinal tapeworm to adapt to dietary stress. Nat Commun (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-69475-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-69475-0