Abstract

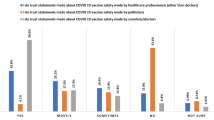

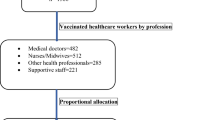

Emergency vaccination programs face unique challenges requiring effective social mobilization strategies, yet comprehensive evaluations of mobilization effectiveness across population settings and temporal phases remain limited. This cross-sectional study conducted from September 2024 to January 2025 included 3048 healthcare workers and 3722 non-healthcare workers in China using multi-stage stratified sampling across eastern, central, and western regions. Participants retrospectively evaluated vaccination attitudes across three COVID-19 vaccination phases: pre-mobilization (2020), in-mobilization (2021-2022), and post-mobilization (2023). Healthcare workers showed increased vaccination willingness in-mobilization (53.5% to 56.2%, p < 0.05), while non-healthcare workers demonstrated sustained increases from 45.1% to 48.1% and 46.5% (p < 0.05). In-mobilization, collective responsibility remained the strongest predictor for healthcare workers (OR = 2.69, 95% CI: 1.85-3.89), while social identity emerged for non-healthcare workers (OR = 3.24, 95% CI: 2.10-4.99). These findings suggest that association between social mobilization and vaccination willingness depends on population-specific intervention strategies acknowledging distinct motivational frameworks and temporal dynamics in emergency vaccination contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Andre, F. E. et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull. World Health Organ. 86, 140–146 (2008).

Ozawa, S. et al. Return on investment from childhood immunization in low- and middle-income Countries, 2011-20. Health Aff. 35, 199–207 (2016).

Shet, A. et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on routine immunisation services: evidence of disruption and recovery from 170 countries and territories. Lancet Glob. Health 10, e186–e194 (2022).

Protecting the public’s health: critical functions of the Section 317 Immunization Program-a report of the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Public Health Rep. 128, 78–95 (2013).

Nelson, C., Lurie, N., Wasserman, J. & Zakowski, S. Conceptualizing and defining public health emergency preparedness. Am. J. Public Health 97, S9–S11 (2007).

Biswas, M. R., Alzubaidi, M. S., Shah, U., Abd-Alrazaq, A. A. & Shah, Z. A scoping review to find out worldwide COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its underlying determinants. Vaccines https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111243 (2021).

Troiano, G. & Nardi, A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health 194, 245–251 (2021).

Lazarus, J. V. et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 27, 225–228 (2021).

Soares, P. et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9030300 (2021).

Loomba, S., de Figueiredo, A., Piatek, S. J., de Graaf, K. & Larson, H. J. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 337–348 (2021).

Roozenbeek, J. et al. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 201199 (2020).

World Health Organization. Advocacy, communication and social mobilization to fight TB : a 10-year framework for action / ASCM Subgroup at Country Level, https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43474/9241594276_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (2006).

World Health Organization. Key Messages for Social Mobilization and Community Engagement in Intense Transmission Areas, https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/136472/WHO_EVD_Guidance_SocMob_14.1_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (2014).

Freudenberg, N. Community capacity for environmental health promotion: determinants and implications for practice. Health Educ. Behav. 31, 472–490 (2004).

Thomson, A., Robinson, K. & Vallée-Tourangeau, G. The 5As: a practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine 34, 1018–1024 (2016).

MacDonald, N. E. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 33, 4161–4164 (2015).

Schmid, P., Rauber, D., Betsch, C., Lidolt, G. & Denker, M. L. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior—a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005 - 2016. PLoS ONE 12, e0170550 (2017).

Paterson, P. et al. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine 34, 6700–6706 (2016).

Verger, P. et al. Vaccine hesitancy among general practitioners and its determinants during controversies: a national cross-sectional survey in France. EBioMedicine 2, 891–897 (2015).

Shekhar, R. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020119 (2021).

Dror, A. A. et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 35, 775–779 (2020).

Freeman, D. et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol. Med. 52, 3127–3141 (2022).

Sallam, M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020160 (2021).

Brewer, N. T., Chapman, G. B., Rothman, A. J., Leask, J. & Kempe, A. Increasing vaccination: putting psychological science into action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 18, 149–207 (2017).

Larson, H. J., Gakidou, E. & Murray, C. J. L. The vaccine-hesitant moment. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 58–65 (2022).

Robinson, E., Jones, A., Lesser, I. & Daly, M. International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. Vaccine 39, 2024–2034 (2021).

Lin, C., Tu, P. & Beitsch, L. M. Confidence and receptivity for COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid systematic review. Vaccines https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010016 (2020).

Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M. & West, R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 6, 42 (2011).

Hassan, E. Recall Bias can be a threat to retrospective and prospective research designs. Internet J. Epidemiol. 3, 4 (2005).

Althubaiti, A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J. Multidiscip. Health. 9, 211–217 (2016).

Mc, N. Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika 12, 153–157 (1947).

Bryk, A. S. & Raudenbush, S. W. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. (Sage Publications, 1992).

Bollen, K. A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. (John Wiley & Sons, 1989).

Gagneux-Brunon, A. et al. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: a cross-sectional survey. J. Hosp. Infect. 108, 168–173 (2021).

Larson, H. J., Jarrett, C., Eckersberger, E., Smith, D. M. D. & Paterson, P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 32, 2150–2159 (2014).

Tom L. Beauchamp, J. F. C. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 8th edn, (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Granovetter, M. S. in Social Networks (ed. Leinhardt, S.) 347–367 (Academic Press, 1977).

Karafillakis, E. et al. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in Europe: a qualitative study. Vaccine 34, 5013–5020 (2016).

Hollmeyer, H. G., Hayden, F., Poland, G. & Buchholz, U. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in hospitals—a review of studies on attitudes and predictors. Vaccine 27, 3935–3944 (2009).

Cialdini, R. B. a. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. (Revised edition. First Collins Business Essentials Edition. (Collins Business, 2007).

Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev. Psychol. 52, 1–26 (2001).

Bandura, A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 31, 143–164 (2004).

Centola, D. How Behavior Spreads: The Science of Complex Contagions. (Princeton University Press, 2018).

Wang, W., Liu, Q. H., Liang, J., Hu, Y. & Zhou, T. Coevolution spreading in complex networks. Phys. Rep. 820, 1–51 (2019).

Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 10, 53 (2015).

Valente, T. W. Social networks and health: models, methods, and applications. 1st ed https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195301014.001.0001 (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Broniatowski, D. A. et al. Weaponized health communication: twitter bots and russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. Am. J. Public Health 108, 1378–1384 (2018).

Kata, A. Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm—an overview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine 30, 3778–3789 (2012).

Kuter, B. J. et al. Perspectives on the receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine: a survey of employees in two large hospitals in Philadelphia. Vaccine 39, 1693–1700 (2021).

Malik, A. A. et al. Behavioral interventions for vaccination uptake: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Policy 137, 104894 (2023).

Betsch, C. et al. Beyond confidence: development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS ONE 13, e0208601 (2018).

Khoury, M. J., Iademarco, M. F. & Riley, W. T. Precision public health for the era of precision medicine. Am. J. Prev. Med. 50, 398–401 (2016).

Dowell, S. F., Blazes, D. & Desmond-Hellmann, S. Four steps to precision public health. Nature 540, 189–191 (2016).

Damschroder, L. J. et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 4, 50 (2009).

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E. & Stange, K. C. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 8, 117 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22BGL246). The funders played no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.X., X.Z., and F.C. conceptualized the study and designed the analytical framework; T.X., H.W., Y.C., H.T., and Y.W. contributed to the data collection and collation; Q.X. contributed to the data analysis; F.C. and L.Q. provided administrative, technical, and material support, supervision, and mentorship; All authors contributed to writing the report and critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Q., Zhang, X., Xie, T. et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of social mobilization for vaccination among healthcare and non-healthcare workers in emergency situations. npj Vaccines (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-026-01392-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-026-01392-1