Abstract

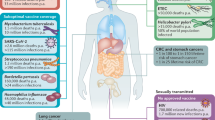

Mucosal surfaces are primary entry sites for many infectious pathogens, yet parenteral vaccination alone often fails to elicit effective mucosal immunity. Mucosally delivered vaccines offer a promising strategy for reinforcing frontline defences and inducing localized, pathogen-specific immune responses. Recent studies indicate that mucosal vaccines elicit tissue-resident memory T and B cells, along with robust local antibody secretion, to prevent infection and transmission. However, achieving sterilizing immunity at mucosal sites proves challenging owing to the complex immune environments consisting of epithelial barriers, varying mucus composition, pH differences and hormonal influences. In this Review, we outline how specialized immune-inductive and effector mechanisms across distinct mucosal compartments contribute to protective immunity and discuss emerging strategies to harness multilayered mucosal immunity to develop safe, effective vaccines that elicit durable protection.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Thompson, M. G. et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines in ambulatory and inpatient care settings. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1355–1371 (2021).

Mohammed, I. et al. The efficacy and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines in reducing infection, severity, hospitalization, and mortality: a systematic review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 18, 2027160 (2022).

Bergwerk, M. et al. Covid-19 breakthrough infections in vaccinated health care workers. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1474–1484 (2021).

Singanayagam, A. et al. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: a prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 183–195 (2022).

Ökten, A. B., Craft, J. E. & Wilen, C. B. Mechanisms of norovirus immunity: implications for vaccine design. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 21, 295–315 (2025).

Belshe, R. B. et al. Efficacy results of a trial of a herpes simplex vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 34–43 (2012).

Rerks-Ngarm, S. et al. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 2209–2220 (2009).

Chen, D. S. & Mellman, I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 39, 1–10 (2013).

Mellman, I., Chen, D. S., Powles, T. & Turley, S. J. The cancer-immunity cycle: indication, genotype, and immunotype. Immunity 56, 2188–2205 (2023).

Chen, K., Magri, G., Grasset, E. K. & Cerutti, A. Rethinking mucosal antibody responses: IgM, IgG and IgD join IgA. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 427–441 (2020).

Holt, P. G., Strickland, D. H., Wikstrom, M. E. & Jahnsen, F. L. Regulation of immunological homeostasis in the respiratory tract. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 142–152 (2008).

Mettelman, R. C., Allen, E. K. & Thomas, P. G. Mucosal immune responses to infection and vaccination in the respiratory tract. Immunity 55, 749–780 (2022).

Nakahashi-Ouchida, R., Fujihashi, K., Kurashima, Y., Yuki, Y. & Kiyono, H. Nasal vaccines: solutions for respiratory infectious diseases. Trends Mol. Med. 29, 124–140 (2023).

Ramirez, S. I. et al. Immunological memory diversity in the human upper airway. Nature 632, 630–636 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Turbinate-homing IgA-secreting cells originate in the nasal lymphoid tissues. Nature 632, 637–646 (2024).

Mora, J. R. & Andrian, U. H. von. Differentiation and homing of IgA-secreting cells. Mucosal Immunol. 1, 96–109 (2008).

Wellford, S. A. et al. Mucosal plasma cells are required to protect the upper airway and brain from infection. Immunity 55, 2118–2134.e6 (2022).

Kazer, S. W. et al. Primary nasal influenza infection rewires tissue-scale memory response dynamics. Immunity 57, 1955–1974.e8 (2024).

Miyamoto, S. et al. Infectious virus shedding duration reflects secretory IgA antibody response latency after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2314808120 (2023).

Marcotte, H. et al. Conversion of monoclonal IgG to dimeric and secretory IgA restores neutralizing ability and prevents infection of Omicron lineages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2315354120 (2024).

Havervall, S. et al. Anti-spike mucosal IgA protection against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1333–1336 (2022).

Gagne, M. et al. Mucosal adenovirus vaccine boosting elicits IgA and durably prevents XBB.1.16 infection in nonhuman primates. Nat. Immunol. 25, 1913–1927 (2024). The study highlights the importance of mucosal boosting for inducing strong IgA responses in the upper respiratory tract, which are crucial for durable protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Kawai, A. et al. Intranasal immunization with an RBD-hemagglutinin fusion protein harnesses preexisting immunity to enhance antigen-specific responses. J. Clin. Invest. 133, e166827 (2023).

Stacey, H. D. et al. Local B-cell immunity and durable memory following live-attenuated influenza intranasal vaccination of humans. Preprint in bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.07.14.664794 (2025).

Lasrado, N. et al. SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1.5 mRNA booster vaccination elicits limited mucosal immunity. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadp8920 (2024).

Declercq, J. et al. Repeated COVID-19 mRNA-based vaccination contributes to SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody responses in the mucosa. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadn2364 (2024).

Pizzolla, A. et al. Resident memory CD8+ T cells in the upper respiratory tract prevent pulmonary influenza virus infection. Sci. Immunol. 2, eaam6970 (2017).

Roukens, A. H. E. et al. Prolonged activation of nasal immune cell populations and development of tissue-resident SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cell responses following COVID-19. Nat. Immunol. 23, 23–32 (2022).

Ssemaganda, A. et al. Expansion of cytotoxic tissue-resident CD8+ T cells and CCR6+CD161+ CD4+ T cells in the nasal mucosa following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Nat. Commun. 13, 3357 (2022).

Whitsett, J. A. & Alenghat, T. Respiratory epithelial cells orchestrate pulmonary innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 16, 27–35 (2015).

Iwasaki, A. & Medzhitov, R. Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nat. Immunol. 16, 343–353 (2015).

Iwasaki, A., Foxman, E. F. & Molony, R. D. Early local immune defences in the respiratory tract. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 7–20 (2017).

Braciale, T. J., Sun, J. & Kim, T. S. Regulating the adaptive immune response to respiratory virus infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 295–305 (2012).

Israelow, B. et al. Adaptive immune determinants of viral clearance and protection in mouse models of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Immunol. 6, eabl4509 (2021).

McMahan, K. et al. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature 590, 630–634 (2021).

Fumagalli, V. et al. Antibody-independent protection against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 challenge conferred by prior infection or vaccination. Nat. Immunol. 25, 633–643 (2024).

Wagstaffe, H. R. et al. Mucosal and systemic immune correlates of viral control after SARS-CoV-2 infection challenge in seronegative adults. Sci. Immunol. 9, eadj9285 (2024).

Zhu, A. et al. Robust mucosal SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells effectively combat COVID-19 and establish polyfunctional resident memory in patient lungs. Nat. Immunol. 26, 459–472 (2025).

Allie, S. R. et al. The establishment of resident memory B cells in the lung requires local antigen encounter. Nat. Immunol. 20, 97–108 (2019).

MacLean, A. J. et al. Regulation of pulmonary plasma cell responses during secondary infection with influenza virus. J. Exp. Med. 221, e20232014 (2024).

MacLean, A. J. et al. Secondary influenza challenge triggers resident memory B cell migration and rapid relocation to boost antibody secretion at infected sites. Immunity 55, 718–733.e8 (2022).

Son, Y. M. et al. Tissue-resident CD4+ T helper cells assist the development of protective respiratory B and CD8+ T cell memory responses. Sci. Immunol. 6, eabb6852 (2021).

Arroyo-Díaz, N. M. et al. Interferon-γ production by Tfh cells is required for CXCR3+ pre-memory B cell differentiation and subsequent lung-resident memory B cell responses. Immunity 56, 2358–2372.e5 (2023).

Huang, X., Yin, Y., Saha, G., Francis, I. & Saha, S. C. A comprehensive numerical study on the transport and deposition of nasal sprayed pharmaceutical aerosols in a nasal-to-lung respiratory tract model. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 42, 2400004 (2025).

Chavda, V. P., Vora, L. K. & Apostolopoulos, V. Inhalable vaccines: can they help control pandemics? Vaccines 10, 1309 (2022).

Agace, W. W. & McCoy, K. D. Regionalized development and maintenance of the intestinal adaptive immune landscape. Immunity 46, 532–548 (2017).

Mowat, A. M. & Agace, W. W. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 667–685 (2014). This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the anatomical, functional and immunological features along the length of the gastrointestinal tract.

Fukata, M. & Arditi, M. The role of pattern recognition receptors in intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 6, 451–463 (2013).

Spencer, J. & Bemark, M. Human intestinal B cells in inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20, 254–265 (2023).

Kulkarni, D. H. & Newberry, R. D. Antigen uptake in the gut: an underappreciated piece to the puzzle? Annu. Rev. Immunol. 43, 571–588 (2025).

Esterházy, D. et al. Compartmentalized gut lymph node drainage dictates adaptive immune responses. Nature 569, 126–130 (2019).

Lane, J. I. et al. Intestinal lymphatic vasculature is functionally adapted to different drainage regions and is altered by helminth infection. J. Exp. Med. 222, e20241181 (2025).

Canesso, M. C. C. et al. Identification of antigen-presenting cell–T cell interactions driving immune responses to food. Science 387, eado5088 (2024).

Mora, J. R. et al. Selective imprinting of gut-homing T cells by Peyer’s patch dendritic cells. Nature 424, 88–93 (2003). This work shows that DCs from gut-associated inductive sites, but not the spleen or non-draining lymph nodes, induce expression of the gut-homing marker α4β7 integrin on naive T cells.

Mora, J. R. et al. Generation of gut-homing IgA-secreting B cells by intestinal dendritic cells. Science 314, 1157–1160 (2006).

Eksteen, B. et al. Gut homing receptors on CD8 T cells are retinoic acid dependent and not maintained by liver dendritic or stellate cells. Gastroenterology 137, 320–329 (2009).

Iwata, M. et al. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity 21, 527–538 (2004). Building on Mora et al. (2003), this work identifies that retinoic acid metabolism by dendritic cells from gut-associated inductive sites is responsible for the imprinting of gut-homing properties on naive T cells.

Iwata, M. & Yokota, A. Retinoic acid production by intestinal dendritic cells. Vitam. Horm. 86, 127–152 (2011).

Müller, S., Bühler-Jungo, M. & Mueller, C. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes exert potent protective cytotoxic activity during an acute virus infection. J. Immunol. 164, 1986–1994 (2000).

Parsa, R. et al. Newly recruited intraepithelial Ly6A+ CCR9+ CD4+ T cells protect against enteric viral infection. Immunity 55, 1234–1249.e6 (2022).

Fuchs, A. et al. Intraepithelial type 1 innate lymphoid cells are a unique subset of IL-12- and IL-15-responsive IFN-γ-producing cells. Immunity 38, 769–781 (2013).

Acker, A. V. et al. A murine intestinal intraepithelial NKp46-negative innate lymphoid cell population characterized by group 1 properties. Cell Rep. 19, 1431–1443 (2017).

FitzPatrick, M. E. B. et al. Human intestinal tissue-resident memory T cells comprise transcriptionally and functionally distinct subsets. Cell Rep. 34, 108661 (2021).

Lyu, Y., Zhou, Y. & Shen, J. An overview of tissue-resident memory T cells in the intestine: from physiological functions to pathological mechanisms. Front. Immunol. 13, 912393 (2022).

Fung, H. Y., Teryek, M., Lemenze, A. D. & Bergsbaken, T. CD103 fate mapping reveals that intestinal CD103− tissue-resident memory T cells are the primary responders to secondary infection. Sci. Immunol. 7, eabl9925 (2022).

Hoesslin, M. V. et al. Secondary infections rejuvenate the intestinal CD103− tissue-resident memory T cell pool. Sci. Immunol. 7, eabp9553 (2022).

Casey, K. A. et al. Antigen-independent differentiation and maintenance of effector-like resident memory T cells in tissues. J. Immunol. 188, 4866–4875 (2012).

Sheridan, B. S. et al. Oral infection drives a distinct population of intestinal resident memory CD8+ T cells with enhanced protective function. Immunity 40, 747–757 (2014). This work demonstrates the requirement of local (that is, oral) infection to drive the development of durable resident memory populations in the gut, as distal (that is, nasal) infection fails to generate comparable local responses.

Mohammed, J. et al. Stromal cells control the epithelial residence of DCs and memory T cells by regulated activation of TGF-β. Nat. Immunol. 17, 414–421 (2016).

Obers, A. et al. Retinoic acid and TGF-β orchestrate organ-specific programs of tissue residency. Immunity 57, 2615–2633.e10 (2024).

Qiu, Z. et al. Retinoic acid signaling during priming licenses intestinal CD103+ CD8 TRM cell differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 220, e20210923 (2023).

Zhang, N. & Bevan, M. J. Transforming growth factor-β signaling controls the formation and maintenance of gut-resident memory T cells by regulating migration and retention. Immunity 39, 687–696 (2013).

Bergsbaken, T., Bevan, M. J. & Fink, P. J. Local inflammatory cues regulate differentiation and persistence of CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells. Cell Rep. 19, 114–124 (2017).

Reina-Campos, M. et al. Tissue-resident memory CD8 T cell diversity is spatiotemporally imprinted. Nature 639, 483–492 (2025).

Mantis, N. J., Rol, N. & Corthésy, B. Secretory IgA’s complex roles in immunity and mucosal homeostasis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 4, 603–611 (2011).

Cerutti, A. The regulation of IgA class switching. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 421–434 (2008).

Fagarasan, S. et al. Critical roles of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in the homeostasis of gut flora. Science 298, 1424–1427 (2002).

Kawamoto, S. et al. The inhibitory receptor PD-1 regulates IgA selection and bacterial composition in the gut. Science 336, 485–489 (2012).

Nakajima, A. et al. IgA regulates the composition and metabolic function of gut microbiota by promoting symbiosis between bacteria. J. Exp. Med. 215, 2019–2034 (2018).

Cazac, B. B. & Roes, J. TGF-β receptor controls B cell responsiveness and induction of IgA in vivo. Immunity 13, 443–451 (2000).

Reboldi, A. et al. IgA production requires B cell interaction with subepithelial dendritic cells in Peyer’s patches. Science 352, aaf4822 (2016).

Siniscalco, E. R., Williams, A. & Eisenbarth, S. C. All roads lead to IgA: mapping the many pathways of IgA induction in the gut. Immunol. Rev. 326, 66–82 (2024).

Haniuda, K. et al. Mucosal viral infection elicits long-lived IgA responses via type 1 follicular helper T cells. Cell 24, 6774–6790.e21 (2025).

Lisicka, W. et al. Immunoglobulin A controls intestinal virus colonization to preserve immune homeostasis. Cell Host Microbe 33, 498–511.e10 (2025).

Zhang, B. et al. Divergent T follicular helper cell requirement for IgA and IgE production to peanut during allergic sensitization. Sci. Immunol. 5, eaay2754 (2020).

Kawamoto, S. et al. Foxp3+ T cells regulate immunoglobulin A selection and facilitate diversification of bacterial species responsible for immune homeostasis. Immunity 41, 152–165 (2014).

Macpherson, A. J. et al. A primitive T cell-independent mechanism of intestinal mucosal IgA responses to commensal bacteria. Science 288, 2222–2226 (2000).

Bunker, J. J. et al. Natural polyreactive IgA antibodies coat the intestinal microbiota. Science 358, eaan6619 (2017).

Palm, N. W. et al. Immunoglobulin A coating identifies colitogenic bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 158, 1000–1010 (2014).

Siniscalco, E. R. et al. Sequential class switching generates antigen-specific gut IgA from IgG1 B cells. Immunity 58, 1–19 (2025).

Zheng, W. et al. Microbiota-targeted maternal antibodies protect neonates from enteric infection. Nature 577, 543–548 (2020).

Shenoy, M. K. et al. Breast milk IgG engages the mouse neonatal immune system to instruct responses to gut antigens. Science 389, eado5294 (2025).

Dean, J. W. et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor cell intrinsically promotes resident memory CD8+ T cell differentiation and function. Cell Rep. 42, 111963 (2023).

Wu, W. et al. Microbiota metabolite short-chain fatty acid acetate promotes intestinal IgA response to microbiota which is mediated by GPR43. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 946–956 (2017).

Kim, M., Qie, Y., Park, J. & Kim, C. H. Gut microbial metabolites fuel host antibody responses. Cell Host Microbe 20, 202–214 (2016).

Wira, C. R., Rodriguez-Garcia, M. & Patel, M. V. The role of sex hormones in immune protection of the female reproductive tract. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 217–230 (2015). This review provides comprehensive details on how oestradiol and progesterone cyclically remodel epithelial barriers, PRR expression and cytokines across the FRT, underpinning timing, route and adjuvant choices for FRT-targeted vaccines.

Herfs, M. et al. A discrete population of squamocolumnar junction cells implicated in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10516–10521 (2012).

Grande, G. et al. Proteomic characterization of the qualitative and quantitative differences in cervical mucus composition during the menstrual cycle. Mol. Biosyst. 11, 1717–1725 (2015).

Critchfield, A. S. et al. Cervical mucus properties stratify risk for preterm birth. PLoS ONE 8, e69528 (2013).

O’Hanlon, D. E., Moench, T. R. & Cone, R. A. Vaginal pH and microbicidal lactic acid when lactobacilli dominate the microbiota. PLoS ONE 8, e80074 (2013).

Chee, W. J. Y., Chew, S. Y. & Than, L. T. L. Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microb. Cell Fact. 19, 203 (2020).

Glick, V. J. et al. Vaginal lactobacilli produce anti-inflammatory β-carboline compounds. Cell Host Microbe 32, 1897–1909.e7 (2024).

Gosmann, C. et al. Lactobacillus-deficient cervicovaginal bacterial communities are associated with increased HIV acquisition in young South African women. Immunity 46, 29–37 (2017).

Anahtar, M. N. et al. Cervicovaginal bacteria are a major modulator of host inflammatory responses in the female genital tract. Immunity 42, 965–976 (2015).

Wira, C. R. et al. Sex hormone regulation of innate immunity in the female reproductive tract: the role of epithelial cells in balancing reproductive potential with protection against sexually transmitted pathogens. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 63, 544–565 (2010).

Zhou, J. Z., Way, S. S. & Chen, K. Immunology of the uterine and vaginal mucosae. Trends Immunol. 39, 302–314 (2018).

Pioli, P. A. et al. Differential expression of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in tissues of the human female reproductive tract. Infect. Immun. 72, 5799–5806 (2004).

Iwasaki, A. Antiviral immune responses in the genital tract: clues for vaccines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 699–711 (2010).

Schaefer, T. M., Wright, J. A., Pioli, P. A. & Wira, C. R. IL-1β-mediated proinflammatory responses are inhibited by estradiol via down-regulation of IL-1 receptor type I in uterine epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 175, 6509–6516 (2005).

Hall, O. J. & Klein, S. L. Progesterone-based compounds affect immune responses and susceptibility to infections at diverse mucosal sites. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 1097–1107 (2017).

Iijima, N., Thompson, J. M. & Iwasaki, A. Dendritic cells and macrophages in the genitourinary tract. Mucosal Immunol. 1, 451–459 (2008).

Evans, J. & Salamonsen, L. A. Inflammation, leukocytes and menstruation. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 13, 277–288 (2012).

Iijima, N. & Iwasaki, A. Tissue instruction for migration and retention of TRM cells. Trends Immunol. 36, 556–564 (2015).

Roychoudhury, P. et al. Tissue-resident T cell derived cytokines eliminate herpes simplex virus-2 infected cells. J. Clin. Investig. 130, 2903–2919 (2020). This work shows that tissue-resident T cell-derived cytokines rapidly clear HSV-2-infected cells in human genital lesions, providing mechanistic evidence that durable protection in the FRT requires establishment of local TRM cells by vaccination.

Shacklett, B. L. Mucosal immunity in HIV/SIV infection: T cells, B cells and beyond. Curr. Immunol. Rev. 15, 63–75 (2019).

Park, C. O. & Kupper, T. S. The emerging role of resident memory T cells in protective immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat. Med. 21, 688–697 (2015).

Koelle, D. M., Frank, J. M., Johnson, M. L. & Kwok, W. W. Recognition of herpes simplex virus type 2 tegument proteins by CD4 T cells infiltrating human genital herpes lesions. J. Virol. 72, 7476–7483 (1998).

Mestecky, J. & Fultz, P. N. Mucosal immune system of the human genital tract. J. Infect. Dis. 179, S470–S474 (1999).

Li, Z. et al. Transfer of IgG in the female genital tract by MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) confers protective immunity to vaginal infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4388–4393 (2011).

Richardson, J. M., Kaushic, C. & Wira, C. R. Polymeric immunoglobin (Ig) receptor production and IgA transcytosis in polarized primary cultures of mature rat uterine epithelial cells. Biol. Reprod. 53, 488–498 (1995).

Usala, S. J., Usala, F. O., Haciski, R., Holt, J. A. & Schumacher, G. F. IgG and IgA content of vaginal fluid during the menstrual cycle. J. Reprod. Med. 34, 292–294 (1989).

Mestecky, J. & Russell, M. W. Induction of mucosal immune responses in the human genital tract. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 27, 351–355 (2000).

Watkins, T. A., Brockhurst, J. K., Germain, G., Griffin, D. E. & Foxman, E. F. Detection of live attenuated measles virus in the respiratory tract following subcutaneous measles-mumps-rubella vaccination. J. Infect. Dis. 231, 1089–1093 (2024).

Topol, E. J. & Iwasaki, A. Operation nasal vaccine — lightning speed to counter COVID-19. Sci. Immunol. 7, eadd9947 (2022).

Routhu, N. K. et al. A modified vaccinia Ankara vector-based vaccine protects macaques from SARS-CoV-2 infection, immune pathology, and dysfunction in the lungs. Immunity 54, 542–556.e9 (2021).

Americo, J. L., Cotter, C. A., Earl, P. L., Liu, R. & Moss, B. Intranasal inoculation of an MVA-based vaccine induces IgA and protects the respiratory tract of hACE2 mice from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2202069119 (2022).

Nouen, C. L. et al. Intranasal pediatric parainfluenza virus-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is protective in monkeys. Cell 185, 4811–4825.e17 (2022).

Hassan, A. O. et al. A single-dose intranasal ChAd vaccine protects upper and lower respiratory tracts against SARS-CoV-2. Cell 183, 169–184.e13 (2020).

Ku, M. W. et al. Intranasal vaccination with a lentiviral vector protects against SARS-CoV-2 in preclinical animal models. Cell Host Microbe 29, 236–249.e6 (2021).

Doremalen, N. van et al. Intranasal ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/AZD1222 vaccination reduces viral shedding after SARS-CoV-2 D614G challenge in preclinical models. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabh0755 (2021).

Ying, B. et al. Mucosal vaccine-induced cross-reactive CD8+ T cells protect against SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1.5 respiratory tract infection. Nat. Immunol. 25, 537–551 (2024).

McMahan, K. et al. Mucosal boosting enhances vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 in macaques. Nature 626, 385–391 (2024).

Madhavan, M. et al. Tolerability and immunogenicity of an intranasally-administered adenovirus-vectored COVID-19 vaccine: an open-label partially-randomised ascending dose phase I trial. eBioMedicine 85, 104298 (2022).

Tscherne, A. & Krammer, F. A review of currently licensed mucosal COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine 61, 127356 (2025).

Kiyono, H. & Ernst, P. B. Nasal vaccines for respiratory infections. Nature 641, 321–330 (2025). This review provides a comprehensive overview of recent advances and challenges in the development of nasal vaccines for respiratory infections.

Carter, N. J. & Curran, M. P. Live attenuated influenza vaccine (FluMist®; FluenzTM): a review of its use in the prevention of seasonal influenza in children and adults. Drugs 71, 1591–1622 (2011).

Mutsch, M. et al. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bell’s palsy in Switzerland. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 896–903 (2004).

Mao, T. et al. Unadjuvanted intranasal spike vaccine elicits protective mucosal immunity against sarbecoviruses. Science 378, eabo2523 (2022).

Kwon, D. I. et al. Mucosal unadjuvanted booster vaccines elicit local IgA responses by conversion of pre-existing immunity in mice. Nat. Immunol. 26, 908–919 (2025).

Moriyama, M. et al. Intranasal hemagglutinin protein boosters induce protective mucosal immunity against influenza A viruses in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2422171122 (2025). Together with Mao et al. (2022) and Kwon et al. (2025), this paper demonstrates how nasal protein boosters can harness pre-existing immunity to elicit robust mucosal recall responses, including local IgA responses, providing a safe and potent mucosal vaccine strategy to enhance mucosal protection against respiratory viruses.

Talaat, K. R. et al. A live attenuated influenza A(H5N1) vaccine induces long-term immunity in the absence of a primary antibody response. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 1860–1869 (2014).

Lin, Y. et al. Sequential intranasal booster triggers class switching from intramuscularly primed IgG to mucosal IgA against SARS-CoV-2. J. Clin. Invest. 135, e175233 (2025).

Jiang, W. et al. Ipsilateral immunization after a prior SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination elicits superior B cell responses compared to contralateral immunization. Cell Rep. 43, 113665 (2024).

Dhenni, R. et al. Macrophages direct location-dependent recall of B cell memory to vaccination. Cell 188, 3477–3496.e22 (2025).

Lederer, K. et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines foster potent antigen-specific germinal center responses associated with neutralizing antibody generation. Immunity 53, 1281–1295.e5 (2020).

Turner, J. S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce persistent human germinal centre responses. Nature 596, 109–113 (2021).

Cirelli, K. M. et al. Slow delivery immunization rnhances HIV neutralizing antibody and germinal center responses via modulation of immunodominance. Cell 177, 1153–1171 (2019).

Lee, J. H. et al. Long-primed germinal centres with enduring affinity maturation and clonal migration. Nature 609, 998–1004 (2022).

Bhagchandani, S. H. et al. Two-dose priming immunization amplifies humoral immunity by synchronizing vaccine delivery with the germinal center response. Sci. Immunol. 9, eadl3755 (2024).

Painter, M. M. et al. Prior vaccination promotes early activation of memory T cells and enhances immune responses during SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection. Nat. Immunol. 24, 1711–1724 (2023). This work shows that prior vaccination accelerates memory T cell activation upon SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection, thereby enhancing the quality and magnitude of recall immune responses.

Bates, T. A. et al. Vaccination before or after SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to robust humoral response and antibodies that effectively neutralize variants. Sci. Immunol. 7, eabn8014 (2022).

Hoffmann, M. et al. Effect of hybrid immunity and bivalent booster vaccination on omicron sublineage neutralisation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 25–28 (2023).

Herremans, T. M. P. T., Reimerink, J. H. J., Buisman, A. M., Kimman, T. G. & Koopmans, M. P. G. Induction of mucosal immunity by inactivated poliovirus vaccine is dependent on previous mucosal contact with live virus. J. Immunol. 162, 5011–5018 (1999).

McConnell, E. L., Basit, A. W. & Murdan, S. Colonic antigen administration induces significantly higher humoral levels of colonic and vaginal IgA, and serum IgG compared to oral administration. Vaccine 26, 639–646 (2008).

Romagnoli, P. A. et al. Differentiation of distinct long-lived memory CD4 T cells in intestinal tissues after oral Listeria monocytogenes infection. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 520–530 (2017).

Cheng, L. & Becattini, S. Local antigen encounter promotes generation of tissue-resident memory T cells in the large intestine. Mucosal Immunol. 17, 810–824 (2024).

Lavelle, E. C. & Ward, R. W. Mucosal vaccines — fortifying the frontiers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 236–250 (2022).

Booth, J. S. et al. Attenuated oral typhoid vaccine Ty21a elicits lamina propria and intra-epithelial lymphocyte tissue-resident effector memory CD8 T responses in the human terminal ileum. Front. Immunol. 10, 424 (2019).

Booth, J. S., Goldberg, E., Barnes, R. S., Greenwald, B. D. & Sztein, M. B. Oral typhoid vaccine Ty21a elicits antigen-specific resident memory CD4+ T cells in the human terminal ileum lamina propria and epithelial compartments. J. Transl. Med. 18, 102 (2020).

Franco, M. A., Angel, J. & Greenberg, H. B. Immunity and correlates of protection for rotavirus vaccines. Vaccine 24, 2718–2731 (2006).

Wright, P. F. et al. Vaccine-induced mucosal immunity to poliovirus: analysis of cohorts from an open-label, randomised controlled trial in Latin American infants. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 1377–1384 (2016).

Marine, W. M., Chin, T. D. Y. & Gravelle, C. R. Limitation of fecal and pharyngeal poliovirus excretion in Salk-vaccinated children. A family study during a type 1 poliomyelitis epidemic. Am. J. Epidemiol. 76, 173–195 (1962).

Hird, T. R. & Grassly, N. C. Systematic review of mucosal immunity induced by oral and inactivated poliovirus vaccines against virus shedding following oral poliovirus challenge. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002599 (2012).

Chan, H. et al. Cold chain and virus-free chloroplast-made booster vaccine to confer immunity against different poliovirus serotypes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 2190–2200 (2016).

Shah, M. P. & Hall, A. J. Norovirus illnesses in children and adolescents. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 32, 103–118 (2018).

Lindesmith, L. et al. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nat. Med. 9, 548–553 (2003).

Ramani, S. et al. Mucosal and cellular immune responses to Norwalk virus. J. Infect. Dis. 212, 397–405 (2015).

Stefan, K. L., Kim, M. V., Iwasaki, A. & Kasper, D. L. Commensal microbiota modulation of natural resistance to virus infection. Cell 183, 1312–1324.e10 (2020).

Ryan, F. J. et al. Bifidobacteria support optimal infant vaccine responses. Nature 641, 456–464 (2025).

Feng, Y. et al. Antibiotic-induced gut microbiome perturbation alters the immune responses to the rabies vaccine. Cell Host Microbe 33, 705–718.e5 (2025).

Oh, J. Z. et al. TLR5-mediated sensing of gut microbiota is necessary for antibody responses to seasonal influenza vaccination. Immunity 41, 478–492 (2014).

Saleem, A. F. et al. Immunogenicity of poliovirus vaccines in chronically malnourished infants: a randomized controlled trial in Pakistan. Vaccine 33, 2757–2763 (2015).

Neidich, S. D. et al. Increased risk of influenza among vaccinated adults who are obese. Int. J. Obes. 41, 1324–1330 (2017).

Honce, R. et al. Diet switch pre-vaccination improves immune response and metabolic status in formerly obese mice. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 1593–1606 (2024).

Becattini, S. et al. Enhancing mucosal immunity by transient microbiota depletion. Nat. Commun. 11, 4475 (2020).

Luccia, B. D. et al. Combined prebiotic and microbial intervention improves oral cholera vaccination responses in a mouse model of childhood undernutrition. Cell Host Microbe 27, 899–908.e5 (2020).

Belkaid, Y. & Harrison, O. J. Homeostatic immunity and the microbiota. Immunity 46, 562–576 (2017).

Naik, S. et al. Commensal–dendritic-cell interaction specifies a unique protective skin immune signature. Nature 520, 104–108 (2015).

Gribonika, I. et al. Skin autonomous antibody production regulates host–microbiota interactions. Nature 638, 1043–1053 (2025).

Bousbaine, D. et al. Discovery and engineering of the antibody response to a prominent skin commensal. Nature 638, 1054–1064 (2025).

Cao, E. Y. et al. The protozoan commensal Tritrichomonas musculis is a natural adjuvant for mucosal IgA. J. Exp. Med. 221, e20221727 (2024).

Ansaldo, E. et al. Akkermansia muciniphila induces intestinal adaptive immune responses during homeostasis. Science 364, 1179–1184 (2019).

Tanoue, T. et al. A defined commensal consortium elicits CD8 T cells and anti-cancer immunity. Nature 565, 600–605 (2019). This work describes the potential of immunogenic commensals to modulate both local and systemic immunity, as transfer of an immunogenic consortia into germ-free mice elicited increased frequencies of intestinal IELs and circulating CD8+ T cells.

Rupp, R. E., Stanberry, L. R. & Rosenthal, S. L. Vaccines for sexually transmitted infections. Pediatr. Ann. 34, 818–824 (2005).

Roden, R. B. S. & Stern, P. L. Opportunities and challenges for human papillomavirus vaccination in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 240–254 (2018).

Schiller, J. T. & Lowy, D. R. Understanding and learning from the success of prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 681–692 (2012).

Shin, H. & Iwasaki, A. A vaccine strategy that protects against genital herpes by establishing local memory T cells. Nature 491, 463–467 (2012). This work introduces the prime and pull vaccine strategy, recruiting parenterally vaccine-primed T cells to the genital mucosa via locally administered chemokines to establish protective TRM cells.

Bernstein, D. I. et al. Successful application of prime and pull strategy for a therapeutic HSV vaccine. NPJ Vaccines 4, 33 (2019).

Bhagchandani, S. H. et al. Bioactive enhanced adjuvant chemokine oligonucleotide nanoparticles (BEACONs) for mucosal vaccination against genital herpes. Preprint in bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.07.31.667899 (2025).

VanBenschoten, H. M. & Woodrow, K. A. Vaginal delivery of vaccines. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 178, 113956 (2021).

McKay, P. F. et al. Intravaginal immunisation using a novel antigen-releasing ring device elicits robust vaccine antigen-specific systemic and mucosal humoral immune responses. J. Control. Release 249, 74–83 (2017).

Cranage, M. P. et al. Antibody responses after intravaginal immunisation with trimeric HIV-1CN54 clade C gp140 in Carbopol gel are augmented by systemic priming or boosting with an adjuvanted formulation. Vaccine 29, 1421–1430 (2011).

Wyatt, T. L., Whaley, K. J., Cone, R. A. & Saltzman, W. M. Antigen-releasing polymer rings and microspheres stimulate mucosal immunity in the vagina. J. Control. Release 50, 93–102 (1998).

Logerot, S. et al. IL-7-adjuvanted vaginal vaccine elicits strong mucosal immune responses in non-human primates. Front. Immunol. 12, 614115 (2021).

Zalenskaya, I. A. et al. Use of contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate is associated with impaired cervicovaginal mucosal integrity. J. Clin. Investig. 128, 4622–4638 (2018).

Medaglini, D., Rush, C. M., Sestini, P. & Pozzi, G. Commensal bacteria as vectors for mucosal vaccines against sexually transmitted diseases: vaginal colonization with recombinant streptococci induces local and systemic antibodies in mice. Vaccine 15, 1330–1337 (1997).

Bermúdez-Humarán, L. G., Kharrat, P., Chatel, J.-M. & Langella, P. Lactococci and lactobacilli as mucosal delivery vectors for therapeutic proteins and DNA vaccines. Microb. Cell Fact. 10, S4 (2011).

Lagenaur, L. A. et al. Prevention of vaginal SHIV transmission in macaques by a live recombinant Lactobacillus. Mucosal Immunol. 4, 648–657 (2011).

Medaglini, D., Oggioni, M. R. & Pozzi, G. Vaginal immunization with recombinant Gram-positive bacteria. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 39, 199–208 (1998).

Chang, C.-H., Simpson, D. A., Li-Yun Chang, T., Xu, Q. & Lewicki, J. A. Lactobacilli expressing biologically active polypeptides and uses thereof. US patent US7833791B2 (2003).

Mestecky, J. The common mucosal immune system and current strategies for induction of immune responses in external secretions. J. Clin. Immunol. 7, 265–276 (1987).

Lai, S. K., Wang, Y.-Y. & Hanes, J. Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to mucosal tissues. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 61, 158–171 (2009).

Eshaghi, B. et al. The role of engineered materials in mucosal vaccination strategies. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 29–45 (2024).

Coffman, R. L., Sher, A. & Seder, R. A. Vaccine adjuvants: putting innate immunity to work. Immunity 33, 492–503 (2010).

Ramirez, J. E. V., Sharpe, L. A. & Peppas, N. A. Current state and challenges in developing oral vaccines. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 114, 116–131 (2017).

Hartwell, B. L. et al. Intranasal vaccination with lipid-conjugated immunogens promotes antigen transmucosal uptake to drive mucosal and systemic immunity. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabn1413 (2022).

Bai, Z. et al. Nanoplatform based intranasal vaccines: current progress and clinical challenges. ACS Nano 18, 24650–24681 (2024).

Pollard, A. J. & Bijker, E. M. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 83–100 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. Charge-assisted stabilization of lipid nanoparticles enables inhaled mRNA delivery for mucosal vaccination. Nat. Commun. 15, 9471 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Advances and prospects of respiratory mucosal vaccines: mechanisms, technologies, and clinical applications. NPJ Vaccines 10, 230 (2025).

Gong, X., Gao, Y., Shu, J., Zhang, C. & Zhao, K. Chitosan-based nanomaterial as immune adjuvant and delivery carrier for vaccines. Vaccines 10, 1906 (2022).

Makadia, H. K. & Siegel, S. J. Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) as biodegradable controlled drug delivery carrier. Polymers 3, 1377–1397 (2011).

Suberi, A. et al. Inhalable polymer nanoparticles for versatile mRNA delivery and mucosal vaccination. Preprint in bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.22.485401 (2022).

Ganesan, S. et al. Intranasal nanoemulsion adjuvanted S-2P vaccine demonstrates protection in hamsters and induces systemic, cell-mediated and mucosal immunity in mice. PLoS ONE 17, e0272594 (2022).

Wu, L., Xu, W., Jiang, H., Yang, M. & Cun, D. Respiratory delivered vaccines: current status and perspectives in rational formulation design. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 14, 5132–5160 (2024).

Crothers, J. W. & Norton, E. B. Recent advances in enterotoxin vaccine adjuvants. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 85, 102398 (2023).

Sundling, C. et al. CTA1-DD adjuvant promotes strong immunity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins following mucosal immunization. J. Gen. Virol. 89, 2954–2964 (2008).

Ensign, L. M. et al. Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for vaginal drug delivery protect against herpes simplex virus. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 138ra79 (2012).

O’Hagan, D. T., Rafferty, D., Wharton, S. & Illum, L. Intravaginal immunization in sheep using a bioadhesive microsphere antigen delivery system. Vaccine 11, 660–664 (1993).

Howe, S. E. & Konjufca, V. H. Protein-coated nanoparticles are internalized by the epithelial cells of the female reproductive tract and induce systemic and mucosal immune responses. PLoS ONE 9, e114601 (2014).

McCright, J. C. & Maisel, K. Engineering drug delivery systems to overcome mucosal barriers for immunotherapy and vaccination. Tissue Barriers 8, 1695476 (2020).

Kim, L. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an oral tablet norovirus vaccine, a phase I randomized, placebo-controlled trial. JCI Insight 3, e121077 (2018).

Flitter, B. A. et al. An oral norovirus vaccine tablet was safe and elicited mucosal immunity in older adults in a phase 1b clinical trial. Sci. Transl. Med. 17, eads0556 (2025).

Flitter, B. A. et al. An oral norovirus vaccine generates mucosal immunity and reduces viral shedding in a phase 2 placebo-controlled challenge study. Sci. Transl. Med. 17, eadh9906 (2025).

Huang, X. et al. Oral delivery of liquid mRNA therapeutics by an engineered capsule for treatment of preclinical intestinal disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 17, eadu1493 (2025).

Holmgren, J. & Czerkinsky, C. Mucosal immunity and vaccines. Nat. Med. 11, S45–S53 (2005).

Bergquist, C., Johansson, E. L., Lagergård, T., Holmgren, J. & Rudin, A. Intranasal vaccination of humans with recombinant cholera toxin B subunit induces systemic and local antibody responses in the upper respiratory tract and the vagina. Infect. Immun. 65, 2676–2684 (1997).

Rudin, A., Johansson, E.-L., Bergquist, C. & Holmgren, J. Differential kinetics and distribution of antibodies in serum and nasal and vaginal secretions after nasal and oral vaccination of humans. Infect. Immun. 66, 3390–3396 (1998).

Hoft, D. F. et al. PO and ID BCG vaccination in humans induce distinct mucosal and systemic immune responses and CD4+ T cell transcriptomal molecular signatures. Mucosal Immunol. 11, 486–495 (2018).

Ramanan, D. et al. An immunologic mode of multigenerational transmission governs a gut Treg setpoint. Cell 181, 1276–1290.e13 (2020).

Jaquish, A. et al. Mammary intraepithelial lymphocytes and intestinal inputs shape T cell dynamics in lactogenesis. Nat. Immunol. 26, 1411–1422 (2025).

Plotkin, S. A. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17, 1055–1065 (2010).

Ghosh, S. et al. Enteric viruses replicate in salivary glands and infect through saliva. Nature 607, 345–350 (2022).

Huang, N. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the oral cavity and saliva. Nat. Med. 27, 892–903 (2021).

Sterlin, D. et al. IgA dominates the early neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabd2223 (2021).

Moutsopoulos, N. M. & Konkel, J. E. Tissue-specific immunity at the oral mucosal barrier. Trends Immunol. 39, 276–287 (2018).

Gaffen, S. L. & Moutsopoulos, N. M. Regulation of host-microbe interactions at oral mucosal barriers by type 17 immunity. Sci. Immunol. 5, eaau4594 (2020).

Hickman, H. D. & Moutsopoulos, N. M. Viral infection and antiviral immunity in the oral cavity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 25, 235–249 (2025).

Eriksson, K., Ahlfors, E., George-Chandy, A., Kaiserlian, D. & Czerkinsky, C. Antigen presentation in the murine oral epithelium. Immunology 88, 147–152 (1996).

Alburquerque, J. B. de et al. Microbial uptake in oral mucosa-draining lymph nodes leads to rapid release of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells lacking a gut-homing phenotype. Sci. Immunol. 7, eabf1861 (2022).

Conti, H. R. et al. Oral-resident natural Th17 cells and γδ T cells control opportunistic Candida albicans infections. J. Exp. Med. 211, 2075–2084 (2014).

Gladiator, A., Wangler, N., Trautwein-Weidner, K. & LeibundGut-Landmann, S. Cutting edge: IL-17-secreting innate lymphoid cells are essential for host defense against fungal infection. J. Immunol. 190, 521–525 (2013).

Kirchner, F. R. & LeibundGut-Landmann, S. Tissue-resident memory Th17 cells maintain stable fungal commensalism in the oral mucosa. Mucosal Immunol. 14, 455–467 (2021).

Conti, H. R. et al. IL-17 receptor signaling in oral epithelial cells is critical for protection against oropharyngeal candidiasis. Cell Host Microbe 20, 606–617 (2016).

Stolley, J. M. et al. Depleting CD103+ resident memory T cells in vivo reveals immunostimulatory functions in oral mucosa. J. Exp. Med. 220, e20221853 (2023).

Schenkel, J. M., Fraser, K. A., Vezys, V. & Masopust, D. Sensing and alarm function of resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 14, 509–513 (2013).

Ingrole, R. S. J. et al. Floss-based vaccination targets the gingival sulcus for mucosal and systemic immunization. Nat. Biomed. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-025-01451-3 (2025).

Kelly, S. H. et al. A sublingual nanofiber vaccine to prevent urinary tract infections. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq4120 (2022).

Wira, C. R. & Fahey, J. V. A new strategy to understand how HIV infects women: identification of a window of vulnerability during the menstrual cycle. AIDS 22, 1909–1917 (2008).

Brotman, R. M., Ravel, J., Bavoil, P. M., Gravitt, P. E. & Ghanem, K. G. Microbiome, sex hormones, and immune responses in the reproductive tract: challenges for vaccine development against sexually transmitted infections. Vaccine 32, 1543–1552 (2014).

Patton, D. L. et al. Epithelial cell layer thickness and immune cell populations in the normal human vagina at different stages of the menstrual cycle. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 183, 967–973 (2000).

Doncel, G. F., Joseph, T. & Thurman, A. R. Role of semen in HIV-1 transmission: inhibitor or facilitator? Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 65, 292–301 (2011).

Kersh, E. N. et al. SHIV susceptibility changes during the menstrual cycle of pigtail macaques. J. Med. Primatol. 43, 310–316 (2014).

Swaims-Kohlmeier, A. et al. Progesterone levels associate with a novel population of CCR5+CD38+ CD4 T cells resident in the genital mucosa with lymphoid trafficking potential. J. Immunol. 197, 368–376 (2016).

Piccinni, M. P. et al. Progesterone favors the development of human T helper cells producing Th2-type cytokines and promotes both IL-4 production and membrane CD30 expression in established Th1 cell clones. J. Immunol. 155, 128–133 (1995).

Vishwanathan, S. A. et al. High susceptibility to repeated, low-dose, vaginal SHIV exposure late in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle of pigtail macaques. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 57, 261–264 (2011).

Kozlowski, P. A. et al. Differential induction of mucosal and systemic antibody responses in women after nasal, rectal, or vaginal immunization: influence of the menstrual cycle. J. Immunol. 169, 566–574 (2002).

Amanna, I. J., Carlson, N. E. & Slifka, M. K. Duration of humoral immunity to common viral and vaccine antigens. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1903–1915 (2007).

Davis, C. W. et al. Influenza vaccine-induced human bone marrow plasma cells decline within a year after vaccination. Science 370, 237–241 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Humoral and cellular immune memory to four COVID-19 vaccines. Cell 185, 2434–2451.e17 (2022).

Srivastava, K. et al. SARS-CoV-2-infection- and vaccine-induced antibody responses are long lasting with an initial waning phase followed by a stabilization phase. Immunity 57, 587–599.e4 (2024).

Muecksch, F. et al. Increased memory B cell potency and breadth after a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA boost. Nature 607, 128–134 (2022).

Nguyen, D. C. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific plasma cells are not durably established in the bone marrow long-lived compartment after mRNA vaccination. Nat. Med. 31, 235–244 (2025).

Kim, W. et al. Germinal centre-driven maturation of B cell response to mRNA vaccination. Nature 604, 141–145 (2022).

Cortese, M. et al. System vaccinology analysis of predictors and mechanisms of antibody response durability to multiple vaccines in humans. Nat. Immunol. 26, 116–130 (2025).

Robinson, M. J. et al. Intrinsically determined turnover underlies broad heterogeneity in plasma-cell lifespan. Immunity 56, 1596–1612.e4 (2023).

Liu, X., Yao, J., Zhao, Y., Wang, J. & Qi, H. Heterogeneous plasma cells and long-lived subsets in response to immunization, autoantigen and microbiota. Nat. Immunol. 23, 1564–1576 (2022).

Tellier, J. et al. Unraveling the diversity and functions of tissue-resident plasma cells. Nat. Immunol. 25, 330–342 (2024).

Holgado, M. P. et al. Mucosal B cell memory selection integrates tissue-specific microbial cues via the IgA BCR. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.04.30.651421 (2025).

Bhattacharya, D. Instructing durable humoral immunity for COVID-19 and other vaccinable diseases. Immunity 55, 945–964 (2022).

Kiyono, H. & Fukuyama, S. NALT- versus PEYER’S-patch-mediated mucosal immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 699–710 (2004).

Nakahashi-Ouchida, R. et al. Cationic nanogel-based nasal therapeutic HPV vaccine prevents the development of cervical cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 17, eado8840 (2025).

Bomsel, M. et al. Immunization with HIV-1 gp41 subunit virosomes induces mucosal antibodies protecting nonhuman primates against vaginal SHIV challenges. Immunity 34, 269–280 (2011).

Czerkinsky, C., Çuburu, N., Kweon, M.-N., Anjuere, F. & Holmgren, J. Sublingual vaccination. Hum. Vaccines 7, 110–114 (2011).

Benito-Villalvilla, C. et al. MV140, a sublingual polyvalent bacterial preparation to treat recurrent urinary tract infections, licenses human dendritic cells for generating Th1, Th17, and IL-10 responses via Syk and MyD88. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 924–935 (2017).

Abraham, S. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the chlamydia vaccine candidate CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes or aluminium hydroxide: a first-in-human, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 19, 1091–1100 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to A.I. D.K. was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2024-00406626). S.H.B. is supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number K00CA264404. S.A.E. is supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease of the NIH (T32-AI007019). The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAMS or NIH. The authors thank A. Ökten and M. Dresler for their careful reading and review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the preparation of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.I. co-founded RIGImmune, Xanadu Bio, Rho Bio and PanV and is a member of the board of directors of Roche Holding Ltd and Genentech. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks Ed Lavelle, Oliver Pabst and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwon, Di., Bhagchandani, S.H., Ehrenzeller, S.A. et al. Harnessing mucosal immunity for protective vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-026-01273-7

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-026-01273-7