Abstract

Live fuel moisture content (LFMC) strongly affects the behavior of wildland fire, resulting in its incorporation into wildfire spread models and danger ratings. In this study, over ten thousand LFMC observations are combined with predictor variables from Landsat imagery and the Weather Research and Forecasting model to train species-specific random forest models that predict the LFMC of four fuel types—chamise, old growth chamise, black sage, and bigpod ceanothus. These models are then utilized to create a historical, 32-year long, LFMC dataset in southern California chaparral. Additionally, the high spatial and temporal sampling frequency of chamise allowed for quantile mapping bias correction to be applied. The final chamise output, which is the most robust, has a mean absolute error of 9.68% and an R2 value of 0.76. The LFMC dataset successfully captures the variability in the annual cycle, the spatial heterogeneity, and the interspecies differences, which makes it applicable for better understanding varying fire season characteristics and landscape level flammability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The LFMC dataset described in this work is available on Dryad (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.rjdfn2zkw). The LFMC observations used for training the models are also available on Dryad. The observations were downloaded from the US National Fuel Moisture Database (https://github.com/wmjolly/pyNFMD) and the Santa Barbara County Fire Department (https://sbcfire.com/wildfire-predictive-services/). The data used for LFMC model predictors is publicly available via the UCSB CLIVAC Lab (https://clivac.eri.ucsb.edu/clivac/SBCWRFD/index.html) and the NASA Landsat program (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srs.2023.100103).

Code availability

The codebase for the creation of this dataset is publicly available as Jupyter Notebooks on GitHub (https://github.com/kcvarga7/sba_lfm_1987-2019). All code was written in Python, with the exception of the GEE script used for downloading Landsat imagery. That GEE script is referenced in the GitHub readme, as well as the applicable Jupyter Notebook.

References

Keane, R. E. Wildland Fuel Fundamentals and Applications. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09015-3. (Springer International, 2015).

Drucker, J. R., Farguell, A., Clements, C. B. & Kochanski, A. K. A live fuel moisture climatology in California. Front. For. Glob. Change 6, 1203536, https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2023.1203536 (2023).

Dennison, P. E. & Moritz, M. A. Critical live fuel moisture in chaparral ecosystems: a threshold for fire activity and its relationship to antecedent precipitation. Int. J. Wildland Fire 18, 1021, https://doi.org/10.1071/WF08055 (2009).

Park, I., Fauss, K. & Moritz, M. A. Forecasting Live Fuel Moisture of Adenostema fasciculatum and Its Relationship to Regional Wildfire Dynamics across Southern California Shrublands. Fire 5, 110, https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5040110 (2022).

Ma, W. et al. Assessing climate change impacts on live fuel moisture and wildfire risk using a hydrodynamic vegetation model. Biogeosciences 18, 4005–4020, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-4005-2021 (2021).

Jolly, W. & Johnson, D. Pyro-Ecophysiology: Shifting the Paradigm of Live Wildland Fuel Research. Fire 1, 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1010008 (2018).

Cakpo, C. B. et al. Exploring the role of plant hydraulics in canopy fuel moisture content: insights from an experimental drought study on Pinus halepensis Mill. and Quercus ilex L. Ann. For. Sci. 81, 26, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13595-024-01244-9 (2024).

Grossiord, C. et al. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytol. 226, 1550–1566, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16485 (2020).

Griebel, A. et al. Specific leaf area and vapour pressure deficit control live fuel moisture content. Funct. Ecol. 37, 719–731, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14271 (2023).

Pivovaroff, A. L. et al. The Effect of Ecophysiological Traits on Live Fuel Moisture Content. Fire 2, 28, https://doi.org/10.3390/fire2020028 (2019).

Jolly, W. M., Conrad, E. T., Brown, T. P. & Hillman, S. C. Combining ecophysiology and combustion traits to predict conifer live fuel moisture content: a pyro-ecophysiological approach. Fire Ecol. 21, 19, https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-025-00361-8 (2025).

Qi, Y., Dennison, P. E., Spencer, J. & Riaño, D. Monitoring Live Fuel Moisture Using Soil Moisture and Remote Sensing Proxies. Fire Ecol. 8, 71–87, https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0803071 (2012).

Brown, T. P. et al. Decoupling between soil moisture and biomass drives seasonal variations in live fuel moisture across co-occurring plant functional types. Fire Ecol. 18, 14, https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-022-00136-5 (2022).

Kozlowski, T. T., Kramer, P. J. & Pallardy, S. G. The Physiological Ecology of Woody Plants. Tree Physiol. 8, 213, https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/8.2.213 (1991).

Wallace, J. M. & Hobbs, P. V. Atmospheric Science: An Introductory Survey. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-0-00034-8. (Elsevier, 2006).

Finney, M. A., McAllister, S. S., Grumstrup, T. P. & Forthofer, J. M. Wildland Fire Behaviour: Dynamics, Principles, and Processes, https://doi.org/10.1071/9781486309092. (CSIRO Publishing, 2021).

Sun, L., Zhou, X., Mahalingam, S. & Weise, D. R. Comparison of burning characteristics of live and dead chaparral fuels. Combust. Flame 144, 349–359, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2005.08.008 (2006).

Jolly, W. M., Freeborn, P. H., Bradshaw, L. S., Wallace, J. & Brittain, S. Modernizing the US National Fire Danger Rating System (version 4): Simplified fuel models and improved live and dead fuel moisture calculations. Environ. Model. Softw. 181, 106181, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2024.106181 (2024).

Capps, S. B., Zhuang, W., Liu, R., Rolinski, T. & Qu, X. Modelling chamise fuel moisture content across California: a machine learning approach. Int. J. Wildland Fire 31, 136–148, https://doi.org/10.1071/WF21061 (2021).

Rao, K., Williams, A. P., Flefil, J. F. & Konings, A. G. SAR-enhanced mapping of live fuel moisture content. Remote Sens. Environ. 245, 111797, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.111797 (2020).

McCandless, T. C., Kosovic, B. & Petzke, W. Enhancing wildfire spread modelling by building a gridded fuel moisture content product with machine learning. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 1, 035010, https://doi.org/10.1088/2632-2153/aba480 (2020).

Peterson, S., Roberts, D. & Dennison, P. Mapping live fuel moisture with MODIS data: A multiple regression approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 112, 4272–4284, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2008.07.012 (2008).

Yebra, M. et al. A global review of remote sensing of live fuel moisture content for fire danger assessment: Moving towards operational products. Remote Sens. Environ. 136, 455–468, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2013.05.029 (2013).

Balaguer-Romano, R. et al. Modeling fuel moisture dynamics under climate change in Spain’s forests. Fire Ecol. 19, 65, https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-023-00224-0 (2023).

Nolan, R. H. et al. Drought-related leaf functional traits control spatial and temporal dynamics of live fuel moisture content. Agric. For. Meteorol. 319, 108941, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2022.108941 (2022).

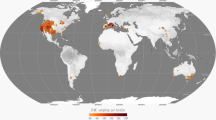

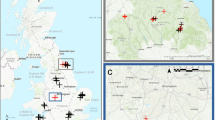

Yebra, M. et al. Globe-LFMC, a global plant water status database for vegetation ecophysiology and wildfire applications. Sci. Data 6, 155, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0164-9 (2019).

Finney, M. A. FARSITE: Fire Area Simulator-Model Development and Evaluation. 10.2737/RMRS-RP-4. RMRS-RP-4, https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/4617 (1998).

Finney, M. A. An Overview of FlamMap Fire Modeling Capabilities. Andrews Patricia Butl. Bret W Comps 2006 Fuels Manag.- Meas. Success Conf. Proc. 28-30 March 2006 Portland Proc. RMRS-P-41 Fort Collins CO US Dep. Agric. For. Serv. Rocky Mt. Res. Stn. P 213-220 041, https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/25948 (2006).

Tymstra, C. Development and Structure of Prometheus: The Canadian Wildland Fire Growth Simulation Model. https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/380448/publication.html. (Northern Forestry Centre, Edmonton, 2010).

Varga, K. et al. Megafires in a Warming World: What Wildfire Risk Factors Led to California’s Largest Recorded Wildfire. Fire 5, 16, https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5010016 (2022).

Seto, D. et al. Simulating Potential Impacts of Fuel Treatments on Fire Behavior and Evacuation Time of the 2018 Camp Fire in Northern California. Fire 5, 37, https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5020037 (2022).

Zahn, S. & Henson, C. Fuel Moisture Collection Methods - A Field Guide. https://www.fs.usda.gov/t-d/pubs/pdf/11511803.pdf (2011).

Jones, C., Carvalho, L. M. V., Duine, G.-J. & Zigner, K. Climatology of Sundowner winds in coastal Santa Barbara, California, based on 30 yr high resolution WRF downscaling. Atmospheric Res. 249, 105305, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2020.105305 (2021).

Crawford, C. J. et al. The 50-year Landsat collection 2 archive. Sci. Remote Sens. 8, 100103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srs.2023.100103 (2023).

CALFIRE FRAP. Vegetation (fveg). https://map.dfg.ca.gov/metadata/ds1327.html (2015).

Sawyer, J. O., Keeler-Wolf, T. & Evens, J. A Manual of California Vegetation, Second Edition. https://vegetation.cnps.org/ (California Native Plant Society, 2009).

United State Goverment. National Fuel Moisture Database. https://github.com/wmjolly/pyNFMD.

Santa Barbara County Fire Department. Live Fuel Moisture Program. https://sbcfire.com/wildfire-predictive-services/.

Jones, C. Santa Barbara County WRF Downscaling Data. https://clivac.eri.ucsb.edu/clivac/SBCWRFD/index.html.

Hong, S.-Y. & Lim, J.-O. J. The WRF Single-Moment 6-Class Microphysics Scheme (WSM6). Asia-Pac. J. Atmospheric Sci. 42, 129–151, https://www2.mmm.ucar.edu/wrf/site_linked_files/phys_refs/micro_phys/WSM6.pdf (2006).

Iacono, M. J. et al. Radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gases: Calculations with the AER radiative transfer models. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD009944. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 113 (2008).

Niu, G.-Y. et al. The community Noah land surface model with multiparameterization options (Noah-MP): 1. Model description and evaluation with local-scale measurements. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JD015139. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 116 (2011).

Nakanishi, M. & Niino, H. Development of an Improved Turbulence Closure Model for the Atmospheric Boundary Layer. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan 87, 895–912, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.87.895 (2009).

Olson, J. B. et al. A Description of the MYNN-EDMF Scheme and the Coupling to Other Components in WRF–ARW. https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/19837 (2019).

Duine, G.-J., Jones, C., Carvalho, L. M. V. & Fovell, R. G. Simulating Sundowner Winds in Coastal Santa Barbara: Model Validation and Sensitivity. Atmosphere 10, 155, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10030155 (2019).

Zigner, K. et al. Evaluating the Ability of FARSITE to Simulate Wildfires Influenced by Extreme, Downslope Winds in Santa Barbara, California. Fire 3, 29, https://doi.org/10.3390/fire3030029 (2020).

Zigner, K. et al. Wildfire Risk in the Complex Terrain of the Santa Barbara Wildland–Urban Interface during Extreme Winds. Fire 5, 138, https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5050138 (2022).

Duine, G.-J., Carvalho, L. M. V. & Jones, C. Mesoscale patterns associated with two distinct heatwave events in coastal Santa Barbara, California, and their impact on local fire risk conditions. Weather Clim. Extrem. 37, 100482, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2022.100482 (2022).

Allen, R., Pereira, L., Raes, D. & Smith, M. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56. https://www.fao.org/4/x0490e/x0490e00.htm (1998).

Ruffault, J., Martin-StPaul, N., Pimont, F. & Dupuy, J. L. How well do meteorological drought indices predict live fuel moisture content (LFMC)? An assessment for wildfire research and operations in Mediterranean ecosystems. Agric. For. Meteorol. 262, 391–401, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.07.031 (2018).

Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Badgley, G., Field, C. B. & Berry, J. A. Canopy near-infrared reflectance and terrestrial photosynthesis. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602244, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1602244 (2017).

McMahon, C. A. et al. A river runs through it: Robust automated mapping of riparian woodlands and land surface phenology across dryland regions. Remote Sens. Environ. 305, 114056, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2024.114056 (2024).

Camprubí, À. C., González-Moreno, P. & Resco de Dios, V. Live Fuel Moisture Content Mapping in the Mediterranean Basin Using Random Forests and Combining MODIS Spectral and Thermal Data. Remote Sens. 14, 3162, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14133162 (2022).

Varga, K. & Jones, C. A. 32-year species-specific live fuel moisture content dataset for southern California chaparral. Dryad https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.rjdfn2zkw (2025).

Hanes, T. L. Succession after Fire in the Chaparral of Southern California. Ecol. Monogr. 41, 27–52, https://doi.org/10.2307/1942434 (1971).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. Random Forests. in The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction (eds Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J.) 587–604, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-84858-7_15. (Springer, New York, NY, 2009).

Meinshausen, N. Quantile Regression Forests. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 7, 983–999, http://jmlr.org/papers/v7/meinshausen06a.html (2006).

Quan, X. et al. Global fuel moisture content mapping from MODIS. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 101, 102354, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2021.102354 (2021).

Moritz, M. A. et al. Beyond a Focus on Fuel Reduction in the WUI: The Need for Regional Wildfire Mitigation to Address Multiple Risks. Front. For. Glob. Change 5, 848254, https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2022.848254 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the NASA Future Investigators in NASA Earth and Space Science and Technology program (Award No. 80NSSC21K1630), the University of California Office of the President Laboratory Fees Program (Grant ID: LFR-20-652467), and The Nature Conservancy’s Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve. We would also like to acknowledge high-performance computing support provided by NCAR’s Computational and Information Systems Laboratory, sponsored by the National Science Foundation Prediction of and Resilience against Extreme Events program (Award No. 1664173). Lastly, we thank Matt Jolly, United States Forest Service Ecologist, for providing essential live fuel moisture observations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kevin Varga: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review and editing. Charles Jones: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-review and editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Varga, K., Jones, C. A 32-year species-specific live fuel moisture content dataset for southern California chaparral. Sci Data (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-026-06794-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-026-06794-3