Abstract

Expansive clay soils cause structural failures in construction due to volume changes with moisture, but hydrated lime effectively stabilizes them by improving shear strength and reducing plasticity. To address environmental concerns with traditional stabilizers like cement, silica fume, a byproduct of the silicon industry, is now being used as a supplementary additive to enhance stabilization. In this study, the combined effects of hydrated lime and silica fume addition on the shear strength and consolidation behaviour of expansive clay soils are presented. An experimental programme was performed in the laboratory using different ratios of lime and silica fume to determine changes in soil properties. Experimental results indicate that the inclusion of silica fume and lime leads to a 35% increase in shear strength and a 28% reduction in compressibility compared to untreated soil. Moreover, the peak deviatoric stress increased from 540.55 kPa in untreated soil to 624.95 kPa in soil stabilized with 9% lime and 9% silica fume. The results clearly demonstrated that the union of these two additives improves shear strength and consolidation characteristics to stabilize expansive clays which is eco-friendlier and more promising solution. The insights obtained from this research will help us to develop soil stabilization techniques for better in-situ soil performances and hence, sustainable construction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Expansive clay soils, also referred to as swelling clays, are known for their volume instability due to changes in moisture content1,2,3. When clay is in a volume instability state, large portions of the ground can swell and shrink, posing significant structural hazards to buildings, roads, pipelines, and other infrastructure4,5,6,7. In drought conditions, expansive soils shrink and crack, leading to foundation settlement, while during wet periods, they swell upward, causing damage to building structures8,9,10,11. This can lead to significant problems, such as foundation failure, cracked pavements, and structural instability. These problems are far too common in the arid and semi-arid climates of certain regions and come at a significant cost associated with routine maintenance and repairs12,13,14. The low shear strength of expansive clays is a significant engineering problem15,16,17. Shear strength defines the soil’s ability to resist failure under loading. Because the delicate clay particles only bond together weakly, expansive soils have low shear strength18,19,20. Furthermore, these soils have a high susceptibility to consolidation which is characterized by a protracted process of soil volume reduction under load over time affecting long-term stability21,22,23. It is crucial to control both the shear strength and consolidation when building infrastructure on expansive soils to maintain its integrity over time.

To enhance the properties of expansive soils, many traditional techniques are developed, and lime—cement is also cited as the common stabilizer used in such stabilization process24,25,26. The lime and soil interaction reduces plasticity and improves stability by activating clay minerals, and the cement and soil combination helps through partial hydration forming pozzolanic reaction products27,28,29. Greater shear strength, lower compressibility, and better swelling control have been established by both additives. But they are not without their downsides—for example, the environmental cost of cement production, one of the biggest contributors to global carbon emissions30,31,32,33. In addition to that, in harsh conditions and with highly active clay soils, the result of using cement may not be favorable34,35,36. In addition, only the cement industry contributes 8% of worldwide CO₂ emissions37,38,39,40. The rising cost of raw materials and concerns over sustainability have sparked interest in alternative, more environmentally friendly methods41,42,43,44.

In recent years, the use of industrial and agricultural waste materials has emerged as a sustainable alternative for soil stabilization45,46,47,48,49. Silica fume, a byproduct of the silicon and ferrosilicon industries, is produced in large quantities11,12. Silica fume offers an environmentally friendly alternative with superior pozzolanic activity. Compared to cement, silica fume and lime stabilization can reduce carbon emissions by 40–50% while achieving comparable soil strength improvements. Globally, around 1 million tons of silica fume are generated annually. Its fine particle size and high pozzolanic activity make it an excellent choice for enhancing soil strength11,12. Silica fume enhances soil stabilization through two primary mechanisms: (i) its ultra-fine particles fill voids between soil particles, increasing density, and (ii) its pozzolanic reactivity promotes the formation of additional calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) compounds, improving cohesion. The small particle size of silica fume allows for better packing and bonding within the soil matrix, reducing permeability and enhancing strength. Additionally, the high surface area of silica fume accelerates pozzolanic reactions, leading to increased formation of cementitious compounds that contribute to long-term stabilization. When mixed with expansive clay, silica fume can fill voids between soil particles, increase particle bonding, and contribute to improved mechanical properties. Besides, lime stabilization has been extensively used in improving the shear strength and reducing plasticity of clay soils. The addition of lime into expansive clay induces pozzolanic reactions leading to the formation of cementitious compounds that stabilize soil particles, thereby enhancing the global stability of the soil21.

Although the individual stabilizing effects of silica fume and lime have been studied in various contexts, research on their combined use in stabilizing expansive clay soil is still limited. Most studies have been performed on the application of these materials in concrete or other soil types, while a combined use has not been investigated for their possible performance enhancement of expansive soils. The synergistic combination between silica fume and lime provides a significant enhancement in improving the shear strength of soil matrix and consolidation behavior than that obtained through incorporating individual one. Silica fume and lime had a pozzolanic reaction and high calcium content could cooperatively alleviate the stabilization of expansive clay in a distinct way. This method also offers a sustainable means by which less-industrial materials such as cement can be used and waste products re-purposed.

This study investigates the combined use of silica fume and lime to enhance the stabilization of expansive clay soils, focusing on improvements in shear strength and consolidation behavior. The novelty lies in the synergistic effect of using two additive materials, which is expected to reduce swell potential, increase durability and strength, and improve long-term performance under load. Through laboratory testing, the research quantifies these benefits, offering a cost-effective and environmentally friendly solution that repurposes industrial waste. The findings contribute to sustainable construction practices and provide a practical approach to addressing geotechnical issues in regions with expansive clays.

Materials and methods

Materials

Soil characteristics

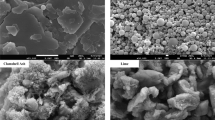

Expansive clay soil (ECS) was sourced from Pahang, Malaysia, at a depth of 1 m. Physical properties of expansive clay soil (ECS) are detailed in Table 1. The particle size distribution was determined through sieve and hydrometer analysis, with the results presented in Fig. 3. The minerals predominantly found in ECS are quartz, illite, kaolinite, and montmorillonite, as indicated in Fig. 4a. Consequently, the soil demonstrates a substantial free-swell index (FSI) value of 57%. It is categorized as CH type (clays of high plasticity) with a liquid limit (LL) and plastic limit (PL) of 51.70 and 22.10, respectively. The morphological-microstructure of ECS is depicted in Fig. 4b. FESEM images depict loosely packed clay platelets with significant voids between the soil particles, suggesting a high potential for swelling upon water absorption. Kaolinite exhibits minimal water absorption and demonstrates very low swelling and shrinkage in response to moisture changes50,51,52,53,54. Conversely, illite and montmorillonite exhibit markedly higher swelling and shrinkage properties. Given these expansive characteristics, it is crucial to treat these clays before undertaking any construction activities to prevent fissures caused by contraction55,56,57,58. Figure 1 shows the microstructure FESEM of expansive clay soil (ECS).

Soil stabilizers characteristics

In the study, lime (L) and silica fume (SF) were utilized as sustainable soil stabilizers to enhance the characteristics of the ECS. L was obtained from CAO Industries Sdn. Bhd., situated in Selangor, Malaysia while, SF is obtained from Elpion Silicon Sdn. Bhd. situated in Selangor, Malaysia. The particle size analysis of L and SF are portrayed in Fig. 2. L and SF obtained in the study were evaluated as non-plastic and non-swelling materials, as highlighted in Table 2. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) test (Fig. 3c and e) performed on L and SF reveals the mineralogical characteristics of the soil stabilizers to be consisting of calcite and portlandite for L while cristobalite for SF. The morphological microstructure of L and SF are depicted in Fig. 3d and f. Hydrated lime, also known as calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)₂], is a widely used material in construction and soil stabilization due to its beneficial chemical and physical properties. It is produced by adding water to quicklime (calcium oxide), resulting in a fine, dry powder. SF is made up of fine, smooth, spherical particles with a high surface area, which boosts its reactivity. Understanding these diverse microstructural characteristics is essential for optimizing the performance of these materials in various applications.

Sample preparation

Stabilization was performed using hydrated lime (9%) and silica fume (3%, 6%, and 9%). Standard testing procedures, including ASTM D422 for particle size distribution and ASTM D5084 for hydraulic conductivity, were followed. The curing protocol adhered to ASTM D1633 for unconfined compressive strength testing, with samples cured for 1, 7, 14, and 30 days. The ECS was placed in a tray and oven-dried at 105 °C for 24 h before being sifted through a 475 µm sieve and crushed. The soil was air-dried for 4 days to ensure even moisture distribution according to AS 1289.9.1.1:2014 standard. After 4 days, the air-dried ECS was mixed with varying moisture levels from 5 to 30% using a compaction test to determine the optimal moisture content. This wide moisture range was selected to represent field conditions typically observed in expansive soils, ensuring practical relevance in real-world applications. The 9% lime dosage was chosen based on unconfined compressive strength tests, which demonstrated that this concentration achieved the highest strength improvements while maintaining economic feasibility. Stabilized samples underwent curing for 1, 7, 14, and 30 days before testing. The ECS samples and stabilized ECS samples prepared for the Consolidated Isotropic Undrained (CIU) Triaxial test had the same density for all specimens tested for the CIU test. The CIU test samples were molded into 38 mm in diameter and 76 mm in height, and the mass was set at 150 g, so the density obtained was 1.740 Mg/m3. The unstabilized and stabilized ECS was poured into the split-form mold, lined with double-layer rubber membranes, and fixed at the triaxial test apparatus. Double-layer rubber membranes were used to avoid any leakage during the testing. In this research, the untreated-ECS sample played the control role of this study. All required materials were dry-mixed using the soil mixer to blend the mixtures thoroughly. Lastly, the samples used to determine the shear strength will undergo a curing process for 1 day, 7 days, 14 days, and 30 days. Figure 4 shows the process flow of sample preparation for the CIU triaxial test.

Determination of soil stabilizers ratios

The maximum percentage of admixture utilized to alter the strength characteristics of the expansive clay soil (ECS) was examined via the unconfined compression test (UCT). Five (5) samples were remolded with a height of 76 mm and a diameter of 38 mm concerning the optimum moisture content (OMC) obtained from the compaction test for each different percentage of the mixture of the soil stabilizers. The calcium oxide (CaO) in lime will react with water to form Ca(OH)₂, which can then interact with the silica and alumina in the soil to create cementitious compounds. This process starts forming calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) and calcium aluminate hydrate (C–A–H).

Silica fume is highly pozzolanic and reacts with the calcium hydroxide already present from the eggshell ash, forming additional C–S–H compounds. This strengthens the soil further by improving particle cohesion and filling voids between particles. Therefore, in this study, the lime was first utilized with the ECS followed by the utilization of SF. All samples used to determine the percentages of soil stabilizers were cured only for one day.

For the first phase (Phase I) of stabilization, the ECS samples were first stabilized and tested using 3%, 6%, and 9% lime. The lime percentages that resulted to the highest unconfined compressive strength (UCS) was fixed as the first soil stabilizer percentage to be mixed with 3%, 6%, and 9% of SF as discussed by Hasan et al.36. Based on the UCT, the highest shear strength was obtained when the ECS was treated with 9% lime with a shear strength value of 15.57 kN/m2. Therefore, 9% of lime was selected and mixed with 3%, 6%, and 9% of SF. The 9% lime dosage was chosen based on unconfined compressive strength tests, which demonstrated that this concentration achieved the highest strength improvements while maintaining economic feasibility. Stabilized samples underwent curing for 1, 7, 14, and 30 days before testing. Figure 5 shows the flow of the soil stabilizers determination used in the study. In Phase II stabilization, the engineering properties of the virgin ECS and stabilized ECS were determined according to the mix designations by proportion dry weight of ECS as highlighted in Table 3.

Consolidated isotropic undrained (CIU) triaxial test

The Consolidated Isotropic Undrained (CIU) Triaxial test was conducted based on BS 1377: Part 7: 1990: 3 as illustrated in Fig. 6 to determine the surging in shear strength of unstabilized and stabilized expansive clay soil (ECS) with various percentages and combinations of lime (L) and silica fume (SF) by taking into consideration the effect of pore water pressure that was developed during the test. Unlike the direct shear test, the triaxial test is chosen owing to the various advantages and benefits of this test. The triaxial test shows similar conditions in which the failure plane is caused naturally without the force of the apparatus. CIU tests were carried out using the GDS Triaxial Fully Automated System. The software that came with the system is the GDSLAB Software Suite which consists of GDSLAB Version 2.3.4 and GDSLAB Reports.

For the CIU test conducted in this study, the samples were subjected to three (3) phases: saturation, consolidation, and shearing, with the cylindrical sample 38 mm in diameter and 76 mm in length. The effective confining pressure of 100 kPa, 200 kPa, and 400 kPa is applied to the specimen during the consolidation stage until it is fully consolidated. Prior to shearing, the specimens were backpressure saturated at 200 kPa isotropically and were saturated until the B value exceeded 0.97 indicating an adequate degree of saturation. Specimens were sheared undrained with a constant strain rate of 0.09 per hour and the tests were terminated when the maximum axial strain reached about 20%. The chosen strain rate was calculated based on the results of consolidation tests as recommended by Marto et al.47.

Results and discussion

The general results obtained from Consolidated Isotropic Undrained (CIU) Triaxial tests are outlined in Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7.

Stress–strain behaviour

The plots of deviatoric stress and the excess pore-water pressure against axial strain for a confining pressure of 100 kPa are illustrated in Figs. 7 and 8, respectively. These results are indicative of tests conducted at other confining pressures. At the beginning of the test, both deviatoric stress and axial strain increase linearly. This illustrates that the samples are undergoing elastic deformation, where the soil particles are compacting and the structure is rearranging under the applied stress. At axial strains between 7 and 20%, the deviatoric stress reaches its maximum value, representing the failure point of the soil. This is where the soil has reached its peak load-bearing capacity before failure. After reaching the peak, the stress either becomes constant or slightly decreases. This behavior suggests that the soil has reached plastic deformation where it can no longer bear additional loads without deforming permanently59,60,61,62. The graph demonstrates how stabilization with L and SF improves both the strength and stability of the expansive clay, as evidenced by higher deviatoric stress at failure.

In the aspects of pore-water pressure, the excess pore-water pressure initially increases alongside axial strain. As the soil is compressed, water in the voids gets pressurized, increasing the pore-water pressure63,64,65,66. At higher strains (after 7–20%), the pore-water pressure levels off. This is typical in undrained conditions where the soil structure can no longer expel water, and the pressure remains constant67,68,69. When compared with virgin ECS samples (untreated soil), the stabilized samples (treated with lime (L) and silica fume (SF)) show an increase in deviatoric stress at failure. This indicates that the stabilization treatment improves the strength and load-bearing capacity of the soil, making it more resistant to failure under stress. The consistent behavior of pore-water pressure with strain shows that the stabilization does not adversely affect the soil’s drainage properties.

The inclusion of L and SF significantly improves the soil’s strength, as indicated by the higher peak deviatoric stress at failure. This is due to the pozzolanic reactions from L and the fine particle structure of SF, which work together to strengthen the bonds between soil particles and reduce voids, enhancing the soil’s load-bearing capacity30,31. The formation of pozzolanic gels, primarily calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) and calcium aluminate silicate hydrate (C–A–S–H), plays a crucial role in enhancing the engineering behavior of expansive clay soils stabilized with lime and silica fume. These gels are produced through pozzolanic reactions between calcium hydroxide (from lime) and the reactive silica and alumina present in both the soil and silica fume. Once formed, the gels fill the voids and micro-cracks within the soil matrix, significantly reducing pore connectivity and limiting water movement. This leads to a denser and more stable structure. Additionally, the hardened gels bond soil particles together, thereby increasing shear strength and reducing compressibility. Over time, continued gel formation during curing results in further microstructural refinement, contributing to long-term strength gain, reduced settlement risk, and overall improvement in soil performance under load.

The rise in pore-water pressure during the test reflects the compression of water in soil voids, which eventually levels off, showing that the stabilization does not negatively impact the soil’s drainage behavior70,71,72,73. Overall, the addition of L and SF strengthens the soil, allowing it to resist failure under higher stress conditions while maintaining its drainage properties. The peak deviatoric stress for untreated soil was recorded at 540.55 kPa, increasing to 624.95 kPa for soil treated with 9% lime and 9% silica fume. The excess pore-water pressure exhibited a decreasing trend with increasing curing periods, indicating improved drainage and soil structure stability. The peak deviatoric stress values at different curing periods highlight the progressive strength enhancement due to stabilization, reinforcing the long-term benefits. The results obtained in this study are aligned with the investigations conducted by Estabragh et al.55, Ding et al.59, and Giger et al.60.

Shear strength parameters

Figure 9 illustrates the effective failure envelopes for ECS samples stabilized with varying percentages of lime (L) and lime–silica fume (L–SF) over 1, 7, 14, and 30 days of curing. The untreated soil consistently shows the lowest shear strength (~ 55 kPa), while samples with higher L–SF content, especially ECS9L9SF, demonstrate notable strength gains over time. Shear strength increases from ~ 86 kPa at 7 days to ~ 92 kPa at 14 days, reaching ~ 97 kPa and ~ 175 kPa effective normal stress by Day 30. These results highlight that higher stabilizer content combined with extended curing significantly enhances shear strength, confirming the effectiveness of L–SF in long-term soil stabilization.

The increase in shear strength and effective normal stress in lime (L) and silica fume (SF) stabilized expansive clay is primarily due to pozzolanic reactions between calcium oxides in lime and clay minerals, forming cementitious compounds like calcium silicate hydrates (C–S–H)37,38,39,40. The fine, reactive particles in SF enhance this process by promoting additional C–S–H formation, filling voids, and improving particle bonding74,75,76,77. This is especially evident in high SF content samples like ECS9L9SF. As curing progresses, continued C–S–H formation results in a denser, more cohesive soil matrix with greater strength and stress resistance. These findings align with those of Bayoumi et al.51, Marinho et al.70, and Ponzoni et al.71.

Figure 10 shows that apparent cohesion in expansive clay soil (ECS) increases with the addition of lime (L) and silica fume (SF), particularly over longer curing periods. The untreated ECS remains constant at 12.9 kPa, indicating no change without chemical stabilization. In contrast, lime-treated samples (ECS3L, ECS6L, ECS9L) show gradual cohesion gains with higher lime content and extended curing. This improvement is due to pozzolanic reactions forming cementitious compounds that bind soil particles and create a stronger, more cohesive matrix over time.

The combination of lime and silica fume (ECS9L3SF, ECS9L6SF, ECS9L9SF) significantly enhances soil cohesion compared to lime alone. Silica fume’s fine, reactive particles promote additional C–S–H formation by reacting with calcium hydroxide, resulting in a denser, stronger matrix13,49. The highest cohesion (18.1 kPa) was achieved in ECS9L9SF after 30 days. Extended curing allows these pozzolanic reactions to fully develop, steadily increasing cohesion. These findings align with studies by Bayoumi et al.51, Marinho et al.70, and Ponzoni et al.71.

Figure 11 shows that the effective friction angle of ECS improves over time with the addition of lime (L) and silica fume (SF). The untreated soil remains constant at 31°, while increasing L content from 3 to 9% raises the friction angle from 31.02° to 31.62° over 30 days due to pozzolanic bonding. The addition of SF, especially at 6% and 9%, further enhances this effect, with the ECS9L9SF mix reaching 34.72° by Day 30. These improvements result from SF’s high reactivity and the cumulative effect of curing, confirming that both additives effectively boost shear strength. These findings align with Javid et al.1 and Ponzoni et al.71.

Figure 11 shows that apparent cohesion in ECS remains constant at 12.9 kN/m2 without additives. Adding 3% lime (ECS3L) increases cohesion slightly from 10 to 11.6 kN/m2 by Day 30, while 6% lime (ECS6L) improves it from 10.3 to 12.2 kN/m2. These results indicate that lime enhances soil strength over time, with higher content yielding better cohesion. Increasing lime content to 9% (ECS9L) notably improves cohesion, suggesting it as an optimal dosage. When combined with silica fume, performance improves further. For example, 9% L with 3% SF (C9L3SF) raised cohesion from 15.5 to 17.1 kN/m2, while 9% L with 9% SF (C9L9SF) achieved the highest value of 18.1 kN/m2 by Day 30. Figure 12 confirms that the optimal L–SF combination enhances cohesion most effectively, with silica fume playing a key role in strengthening soil over time.

The increase in apparent cohesion of stabilized ECS is due to pozzolanic reactions between lime (L) and silica fume (SF), forming cementitious compounds like C–S–H that enhance particle bonding. Lime contributes calcium, while SF’s fine, reactive particles fill voids and promote additional C–S–H formation, resulting in a denser, stronger soil structure78,79,80. As shown in Fig. 12, improvements taper off beyond 9% L, suggesting a saturation point. The optimal combination of 9% L and 9% SF maximizes this synergistic effect, significantly enhancing shear strength for effective soil stabilization.

Figure 13 shows that the effective friction angle of ECS remains constant at 31° without additives. With 3% lime (ECS3L), it increases slightly from 31.02 to 31.18° over 30 days. A higher lime content (6%) results in a more noticeable improvement, with the angle rising from 31.07 to 31.39°, indicating enhanced shear strength with increased lime dosage. With 9% lime (ECS9L), the friction angle increases from 31.14 to 31.62° over 30 days, confirming a positive correlation between lime dosage and shear strength. Adding silica fume further enhances this effect: ECS9L3SF increases from 32.27 to 33.87°, ECS9L6SF reaches 34.28°, and ECS9L9SF achieves the highest value of 34.72° by Day 30. These results show that silica fume significantly improves soil stability beyond lime alone.

Apparent cohesion increased from 12.9 kPa (untreated) to 18.1 kPa with 9% lime and 9% silica fume, a 40% improvement. The effective friction angle also rose from 31.0 to 34.7°, indicating stronger interparticle bonding and load-bearing capacity. These gains result from pozzolanic reactions where lime forms C–S–H compounds that enhance particle adhesion and compaction38,47. Silica fume accelerates these reactions and fills voids with fine particles, creating a denser, more interlocked soil structure. Together, L and SF significantly improve cohesion and shear strength, especially with higher dosages and longer curing.

Consolidation and compressibility

The data presented in Fig. 14 shows the effects of using lime (L) and lime-silica fume (L-SF) combinations on the time taken by expansive clay soil (ECS) to achieve full consolidation in relation to various effective confining pressures and curing periods. The control group (ECS) without additives reveals consolidation times stay the same over curing periods, hence curing in itself does not significantly affect the consolidation time. In the absence of L, most exhibits near 99% consolidation in as little as a few minutes for this material at both higher pressure (~ 800 kPa) and lower pressure (100 kPa), while with 3% and 6% L added to the slurry, there is a marked increase in the time necessary for first consolidation at low pressures (100 kPa) showing an initial slowing of consolidation by L. This means that the structure of the soil is getting more resistant to compression in the early stages. This could be an indication that under higher pressure (200 and 400 kPa) the soil is still stabilizing more than when under lesser pressure, so over time, with just L alone, densification times at high pressures get a little slower as it cures. The inclusion of silica fume, particularly in the 9% L and 6–9% silica fume combinations, drastically improves consolidation times, especially at high pressures. For instance, the time to full consolidation is reduced significantly with stabilizer addition. At an effective confining pressure of 400 kPa, untreated soil required 34 min to consolidate, whereas soil treated with 9% lime and 9% silica fume consolidated in 25 min. The reduction in void ratio and enhanced particle bonding due to silica fume contributed to accelerated consolidation. Silica fume reduces voids and promotes stronger soil bonds, thereby expediting the consolidation process. Tables 8 and 9 shows the effects of additive type, curing period, and confining pressure on the coefficient of consolidation, cv and coefficient of compressibility, mv of the expansive soil.

Lime (L) primarily contributes through pozzolanic reactions. Lime acts mainly through cation exchange and pozzolanic reactions, initially flocculating clay particles and later forming cementitious compounds such as C–S–H, which increase strength and reduce compressibility. However, in early stages, lime can slow consolidation due to structural stiffening. In contrast, silica fume—because of its ultrafine particle size and high pozzolanic reactivity—fills micropores and rapidly contributes to gel formation, accelerating consolidation and improving drainage. These mechanisms operate synergistically when combined, with lime providing long-term strength and silica fume enhancing early densification and pore pressure dissipation12,48.

In addition, the incorporation of silica fume (SF) in the L-SF mixture is capable of further stabilizing this process because of its high reactivity and fine particle size. The fume itself increases the pozzolanic activity and hence more formation of C–S–H forming additional plugs to microvoids developed in the soil matrix. It flows in a way to create a smaller, denser structure that facilitates more effective water drainage and reduced pressure dissipation of pores under load, while this property was irrelevant for sampling purposes70,71. In this case, the marked reduction in consolidation time experienced at higher pressures with the L-SF combination (e.g., > 34 − 25 min at 400 kPa) could be a result of the overall improvement of compactness and transient permeability of soil due to the use of silica fume. It helps to dissipate the pore water pressures within the pores at higher confining pressure faster which in allows faster consolidation. Moreover, the full development of these types of chemical reactions is required for curing time which is why compaction improves with time. The process results in the pozzolanic reactions between L, SF, and soil being more fully developed into a hardened configuration that is a stronger and more stable form capable of handling higher stress or pressure effectively as the soil cures longer.

Figure 15 shows the effect of utilizing L and L-SF on the coefficient of consolidation of stabilized ECS at effective confining pressures of 100, 200, and 400 kPa treated at various curing periods. The figure demonstrates the correlation between the coefficient of consolidation (cv) and effective confining pressures (σ3’) for ECS-stabilized soils treated with various percentages of L and L-SF, observed over curing periods of 1, 7, 14, and 30 days. For the control sample (ECS), the coefficient of consolidation remains constant across all curing periods, with values steadily increasing as the confining pressure rises, but with no significant change over time. This suggests that ECS alone does not exhibit improved consolidation characteristics with extended curing. In contrast, the addition of L significantly improves consolidation, as seen in the samples treated with 3%, 6%, and 9% ESA (ECS3L, ECS6L, and ECS9L). For example, in the ECS3L sample at 100 kPa, the cv increases from 276.74 m2/year on day 1 to 323.88 m2/year on day 30, reflecting an enhanced consolidation behavior over time. This improvement is even more pronounced when silica fume is incorporated. Samples treated with both L and SF, such as ECS9L3SF and ECS9L9SF, show higher consolidation rates. For instance, at 400 kPa, the ECS9L3SF reaches a cv of 469.49 m2/year by day 30, while ECS9L9SF reaches 500.54 m2/year. This trend highlights the combined effect of L and SF in improving soil stabilization, with higher dosages leading to better consolidation performance, particularly under higher pressures and longer curing periods. These findings emphasize the critical role of both curing time and additive composition in optimizing soil consolidation properties.

As a case in point, the value of cv at 100 kPa for the ECS3L composite increases from 276.74 m2/year on day 1 to 355.17 m2/year on day 30 signifying an improved consolidation behavior with time (Fig. 15). This type of enhancement is even more noticeable when SF is added. Results show that the highest rates of consolidation were obtained for samples treated with L (ECS9L3SF, ECS9L9SF). For example, at 400 kPa, the ECS9L3SF grows to a cv value of 469.49 m2/year at day 30 whereas ECS9L9SF grows to 500.54 m2/year. This trend demonstrates a synergetic role of L and SF to enhance soil stabilization, and the increased dosage results in a more consolidation effect, especially under higher pressure and longer curing periods. Such results highlight the importance of both curing time and additive formulation to enhance soil consolidation characteristics.

Figure 16 shows the effect of utilizing L and L-SF on the coefficient of volume compressibility of stabilized ECS at effective confining pressures of 100, 200, and 400 kPa treated at various curing periods. The graph illustrates the relationship between the coefficient of volume compressibility (mv) and effective confining pressures (σ3) for ECS-stabilized soils treated with varying amounts of L and L-SF over different curing periods. In the control sample (ECS), the mv remains constant across all curing periods, showing no improvement in compressibility over time. However, when L is added, a noticeable reduction in mv occurs, indicating that the soil becomes less compressible as curing progresses. For instance, the ECS3L sample (with 3% L) shows a decrease in mv from 0.78 m2/MN on day 1 to 0.74 m2/MN by day 30 at 100 kPa, reflecting improved resistance to compression. The effect is even more significant when both L and SF are used together, as seen in the ECS9L9SF sample (9% L and 9% SF), where mv decreases from 0.64 m2/MN to 0.59 m2/MN over the same period at 100 kPa.

The coefficient of volume compressibility (mv) decreased from 0.78 m2/MN in untreated soil to 0.59 m2/MN in stabilized soil, highlighting a 28% reduction in compressibility. This finding correlates with enhanced structural integrity and reduced settlement risks in real-world applications, where minimizing compressibility is crucial for maintaining long-term stability. Both L and SF contribute to fortifying the soil composition, rendering it less prone to deformation under heightened loads even after prolonged curing. The discernible drop in compressibility indicates the stabilized substrate attains greater density and stability over time; properties pivotal to minimizing subsidence and upgrading the structural integrity of geotechnical constructions74. Moreover, within the same specimen, higher compressed weights further compressed the already compressed substance. The synergistic blend of agents produces a bolstering effect that endures and amplifies with developing dynamic stress.

The observed increase in the coefficient of consolidation (cv) from 276.74 m2/year in untreated soil to 500.54 m2/year in the sample stabilized with 9% lime and 9% silica fume which indicates a significantly faster rate of excess pore water pressure dissipation. This implies a reduced risk of post-construction settlement and shorter stabilization periods, making the treated soil more suitable for time-sensitive infrastructure projects. Similarly, the reduction in the coefficient of volume compressibility (mv) from 0.78 m2/MN to 0.59 m2/MN reflects enhanced structural rigidity and reduced compressibility, both of which are critical for minimizing long-term deformation under loading. These improvements exceed typical benchmarks reported in the literature by Marto et al.47, where lime or cement stabilization alone generally results in 10–20% increases in cv and 15–25% reductions in mv. Thus, the lime–silica fume combination in this study demonstrates a more effective and sustainable stabilization alternative, particularly for expansive clays.

Initially, pozzolanic reactions play a pivotal role in improving compressibility. The expansive soil additive contains chemically active materials that, when combined with moisture, yield calcium silicate hydrates, bonding soil grains into a cohesive framework. This reaction diminishes voids amid particles, making the ground denser and more resistant to pressure loading over time. As the percentage of expansive soil additive rises, such interactions become more pronounced, leading to an increasing decrease in compressibility75,76. Additionally, the introduction of silica fume further enhances this impact. Possessing ultrafine grains and a large surface area, silica fume catalyzes the pozzolanic reaction at an accelerated pace. When blended with expansive soil additive, silica fume contributes to forming even more calcium silicate hydrate compounds, filling pores between soil constituents and fabricating a tighter, more coherent soil architecture. This generates a more rigid and less compressible material, particularly at higher silica fume concentrations79,80. Moreover, prolonged curing permits these reactions to completely develop. Gradually, the ongoing chemical changes fortify the soil framework, further reducing compressibility. The data indicates that the longer the curing period, the more significant the reduction in compressibility, as the soil becomes increasingly resistant to volume fluctuation under loading81,82,83. Lastly, the decrease in compressibility with higher effective confining pressures can be attributed to the soil becoming more packed under force. As pressure rises, the soil grains are compelled nearer together, diminishing void space and rendering the soil even less compressible. The combination of lime and silica fume not only enhances soil stability but also aligns with sustainable construction goals by reducing the need for cement84. The optimal stabilizer ratio (9% lime and 9% silica fume) provides diminishing returns beyond this threshold, ensuring cost-effectiveness and material efficiency. Additionally, this stabilization approach reduces the dependency on conventional cement, which is known for its high carbon footprint.

Conclusions

This investigation unveils the considerable improvements in the shear strength and consolidation behavior of expansive clay soils stabilized with lime and silica fume. The combination of lime and silica fume demonstrated an enhancement of the soil’s mechanical properties, notably increasing shear strength while reducing compressibility. The pozzolanic reactions facilitated by lime, and further accelerated by the inclusion of silica fume, generated a denser soil matrix, improving its stability under loading. Consolidation times were also noticeably reduced, especially at higher effective confining pressures, indicating the effectiveness of these stabilizers in hastening soil settlement. This study demonstrates that the incorporation of silica fume and lime significantly improves the shear strength and consolidation behavior of expansive clay soil. Quantitative improvements include a 35% increase in shear strength, a 28% reduction in compressibility, and a 26% faster consolidation time occurred in samples stabilized with 9% lime and 9% silica fume, compared to untreated expansive clay. The results suggest that this stabilization method is a viable, eco-friendly alternative to cement, with practical implications for geotechnical engineering and sustainable construction. Further research should explore the long-term durability of stabilized soils under varying environmental conditions and assess the economic feasibility of large-scale implementation. Additionally, reaffirming the role of lime-silica fume stabilization in sustainable construction practices would further emphasize its significance in reducing environmental impact.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Javid, A., Pandey, B. K. & Srijan. Performance evaluation of clayey soil considering impact of lime during electrokinetic consolidation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-023-08148-2

A Sharma A Sharma K Singh 2022 Bearing capacity of sand admixed pond ash reinforced with natural fiber J. Nat. Fibers https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2020.1848699

KK Gautam RK Sharma A Sharma 2021 Effect of municipal solid waste incinerator ash and lime on strength characteristics of black cotton soil Lect. Notes Civil Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9554-7_10

MSI Zaini M Hasan MF Zolkepli 2023 Influence of Alstonia Angustiloba tree water uptake on slope stability: A case study at the unsaturated slope, Pahang Malaysia Bull. Geol. Soc. Malaysia https://doi.org/10.7186/bgsm75202305

MSI Zaini MF Ishak MF Zolkepli 2019 Forensic assessment on landfills leachate through electrical resistivity imaging at Simpang Renggam in Johor, Malaysia IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/669/1/012005

MSI Zaini MF Ishak MF Zolkepli 2020 Monitoring soil slope of tropical residual soil by using tree water uptake method IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/736/7/072018

Zaini, M. S. I., & Hasan, M. Application of Electrical Resistivity Tomography in Landfill Leachate Detection Assessment. In: Anouzla, A., Souabi, S. (eds) A Review of Landfill Leachate. Springer, Cham. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-55513-8_1

N Mohamed 2025 Characterization of residual soil properties on slope in Dusun UTM Johor. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Mech. https://doi.org/10.37934/aram.132.1.1125

N Mohamed 2024 Analysis of residual soil properties on slope: A study in Dusun, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Johor. Int. J. Integr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.30880/ijie.2024.16.09.007

X Liu X Xu L Huang X Wei H Lan 2024 On characteristics of K0 value and shear behaviour of loess using triaxial test Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42248-1

MSI Zaini 2022 The effect of utilizing silica fume and eggshell ash on the geotechnical properties of soft kaolin clay J. Teknol. https://doi.org/10.11113/jurnalteknologi.v84.17115

MSI Zaini M Hasan 2023 Effects of industrial and agricultural recycled waste enhanced with lime utilisation in stabilising kaolinitic soil Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. https://doi.org/10.30880/ijscet.2023.14.04.025

MSI Zaini M Hasan W Md Jariman 2024 Strength of Kaolinitic Clay soil stabilized with lime and palm oil fuel ash CONS. https://doi.org/10.15282/construction.v4i1.10517

MSI Zaini M Hasan AS Zulkafli 2024 Basic and morphological properties of Bukit Goh Bauxite CONS. https://doi.org/10.15282/construction.v4i2.10736

M Singh K Singh A Sharma 2022 Strength characteristics of clayey soil stabilized with brick kiln dust and sisal fiber Lect. Notes Civil Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6557-8_75

D Anand RK Sharma A Sharma 2021 Improving swelling and strength behavior of black cotton soil using lime and quarry dust Lect. Notes Civil Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9554-7_54

S Almuaythir MSI Zaini M Hasan MI Hoque 2024 Sustainable soil stabilization using industrial waste ash: Enhancing expansive clay properties Heliyon. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39124

MF Zolkepli MF Ishak MSI Zaini 2019 Slope stability analysis using modified Fellenius’s and Bishop’s method IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/527/1/012004

MSI Zaini M Hasan 2024 Shear strength of soft soil reinforced with singular bottom ash column CONS. https://doi.org/10.15282/construction.v4i1.10448

MSI Zaini M Hasan 2024 Stabilization of expansive soil using silica fume and lime CONS. https://doi.org/10.15282/construction.v4i1.10484

A Sharma RK Sharma 2021 Sub-grade characteristics of soil stabilized with agricultural waste, constructional waste, and lime Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-020-02047-8

S Rana S Singh A Sharma 2024 Utilizing bottom ash, lime and sodium hexametaphosphate in expansive soil for flexible pavement subgrade design Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41939-023-00210-8

JC Chai HT Fu 2021 Effect of chemical additives on the consolidation behavior of slurries Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 39 7 790 797 https://doi.org/10.1080/1064119X.2020.1762809

MF Zolkepli MF Ishak MS Zaini 2018 Analysis of slope stability on tropical residual soil Int. J. Civil Eng. Technol. 9 2 402 416

MSI Zaini M Hasan N Yusuf 2024 Strength and compressibility of soft clay reinforced with group crushed polypropylene columns CONS. https://doi.org/10.15282/construction.v4i2.10737

MSI Zaini M Hasan MKF Jamal 2024 Strength of problematic soil stabilised with gypsum and palm oil fuel ash CONS. https://doi.org/10.15282/construction.v4i2.10735

JR Goh MF Ishak MSI Zaini MF Zolkepli 2020 Stability analysis and improvement evaluation on residual soil slope: Building cracked and slope failure IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/736/7/072017

LJ Yue MF Ishak MSI Zaini MF Zolkepli 2019 Rainfall induced residual soil slope instability: Building cracked and slope failure IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/669/1/012004

AR Suwito M Hasan MSI Zaini 2024 Basic geotechnical characteristic of soft clay stabilised with cockle shell ash and silica fume CONS. https://doi.org/10.15282/construction.v4i2.11110

H Hailemariam F Wuttke 2022 An experimental study on the effect of temperature on the shear strength behavior of a silty clay soil Geotechnics https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics2010011

U Khalid ZU Rehman C Liao K Farooq H Mujtaba 2019 Compressibility of compacted clays mixed with a wide range of bentonite for engineered barriers Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 44 5 5027 5042 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-018-03693-7

NM Chiloane G Sengani F Mulenga 2024 An experimental and numerical study of the strength development of layered cemented tailings backfill Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51464-2

J Wang PN Hughes CE Augarde 2024 Towards a predictive model of the shear strength behaviour of fibre reinforced clay Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2023.2214596

J Hao 2024 Effects of clay grains on the shear properties of unsaturated loess and microscopic mechanism Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73413-9

MF Zolkepli 2021 Slope mapping using unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) Turkish J. Comput. Math. Educ. https://doi.org/10.17762/turcomat.v12i3.1005

M Hasan 2021 Effect of optimum utilization of silica fume and eggshell ash to the engineering properties of expansive soil J. Mater. Res. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.07.023

MSI Zaini M Hasan 2023 Effect of optimum utilization of silica fume and lime on the stabilization of problematic soils Int. J. Integr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.30880/ijie.2023.15.01.032

S Mahvash S López-Querol A Bahadori-Jahromi 2017 Effect of class F fly ash on fine sand compaction through soil stabilization Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00274

MSI Zaini M Hasan MF Zolkepli 2022 Urban landfills investigation for leachate assessment using electrical resistivity imaging in Johor Malaysia Environ. Challenges https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100415

MSI Zaini M Hasan WNBW Jusoh 2023 Utilization of bottom ash waste as a granular column to enhance the lateral load capacity of soft kaolin clay soil Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-25966-x

MSI Zaini M Hasan KA Masri 2023 Stabilization of kaolinitic soil using crushed tile column Mag. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.34910/MCE.123.4

MSI Zaini M Hasan 2023 Effectiveness of silica fume eggshell ash and lime use on the properties of Kaolinitic Clay Int. J. Eng. Technol. Innov. https://doi.org/10.46604/ijeti.2023.11936

M Hasan 2021 Stabilization of kaolin clay soil reinforced with single encapsulated 20mm diameter bottom ash column IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/930/1/012099

M Hasan 2021 Sustainable ground improvement method using encapsulated polypropylene (PP) column reinforcement IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/930/1/012016

A Wahab 2022 Physical properties of undisturbed tropical peat soil at Pekan district, Pahang West Malaysia Int. J. Integr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.30880/ijie.2022.14.04.031

MF Ishak 2021 Verification of tree induced suction with numerical model Phys. Chem. Earth https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2021.102980

A Marto M Hasan M Hyodo AM Makhtar 2014 Shear strength parameters and consolidation of clay reinforced with single and group bottom Ash columns Arab. J. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-013-0933-2

MF Zolkepli 2021 Application of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) for slope mapping at Pahang matriculation college Malaysia Phys. Chem. Earth https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2021.103003

R Hu M Zhang J Wang 2023 An investigation into the influence of sample height on the consolidation behaviour of dredged silt Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app131810419

MF Ishak 2021 The effect of tree water uptake on suction distribution in tropical residual soil slope Phys. Chem. Earth https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2021.102984

A Bayoumi M Chekired M Karray 2023 Experimental approach for assessing dissipated excess pore pressure-induced settlement Can. Geotech. J. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2022-0063

A Tsutsumi H Tanaka 2012 Combined effects of strain rate and temperature on consolidation behavior of clayey soils Soils Found. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2012.02.001

VN Khatri RK Dutta G Venkataraman R Shrivastava 2016 Shear strength behaviour of clay reinforced with treated coir fibres Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPci.7917

IA Khasib NN Nik Daud M Izadifar 2023 Consolidation behaviour of palm-oil-fuel-ash-based geopolymer treated soil Geotech. Res. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgere.23.00013

AR Estabragh M Moghadas M Moradi AA Javadi 2017 Consolidation behavior of an unsaturated silty soil during drying and wetting Soils Found. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2017.03.005

MSI Zaini 2020 Granite exploration by using electrical resistivity imaging (ERI): A case study in Johor Int. J. Integr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.30880/ijie.2020.12.08.032

MF Ishak MSI Zaini 2018 Physical analysis work for slope stability at Shah Alam, Selangor J. Phys. Conf. Ser. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/995/1/012064

MF Ishak BK Koay MS Zaini MF Zolkepli 2018 Investigation and monitoring of groundwater level: Building crack near to IIUM Kuantan Int. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 5 3 51 56

J Ding X Feng Y Cao S Qian F Ji 2018 Consolidated undrained triaxial compression tests and strength criterion of solidified dredged materials Adv. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9130835

SB Giger RT Ewy V Favero R Stankovic LM Keller 2018 Consolidated-undrained triaxial testing of Opalinus Clay: Results and method validation Geomech. Energy Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gete.2018.01.003

AK Sharma PV Sivapullaiah 2021 Studies on the compressibility and shear strength behaviour of fly ash and slag mixtures Int. J. Geosynth. Gr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40891-021-00264-z

T Karademir 2022 Lime stabilization of clayey landfill base liners: Consolidation behavior and hydraulic properties Environ. Res. Technol. https://doi.org/10.35208/ert.860623

K Kan B François 2023 Triaxial tension and compression tests on saturated lime-treated plastic clay upon consolidated undrained conditions J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2023.03.017

YM Kwon I Chang GC Cho 2023 Consolidation and swelling behavior of kaolinite clay containing xanthan gum biopolymer Acta Geotech. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-023-01794-8

N Jarad O Cuisinier F Masrouri 2019 Effect of temperature and strain rate on the consolidation behaviour of compacted clayey soils Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2017.1311806

H Awang AF Salmanfarsi MSI Zaini MAF Mohamad Yazid MI Ali 2021 Investigation of groundwater table under rock slope by using electrical resistivity imaging at Sri Jaya, Pahang, Malaysia IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/682/1/012017

M Hasan 2021 Geotechnical properties of bauxite: A case study in Bukit Goh, Kuantan, Malaysia IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/930/1/012098

MSI Zaini M Hasan 2024 Effect of Alstonia Angustiloba tree moisture absorption on the stabilization of unsaturated residual soil slope Int. J. Env. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-024-05550-7

Z Liu Y Liu M Bolton DEL Ong E Oh 2020 Effect of cement and bentonite mixture on the consolidation behavior of soft estuarine soils Int. J. Geomate https://doi.org/10.21660/2019.64.19076

FAM Marinho OM Oliveira H Adem S Vanapalli 2013 Shear strength behavior of compacted unsaturated residual soil Int. J. Geotech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1179/1938636212Z.00000000011

E Ponzoni S Muraro A Nocilla C Jommi 2023 Deformational response of a marine silty-clay with varying organic content in the triaxial compression space Can. Geotech. J. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2023-0058

A Sridharan K Prakash 1999 Mechanisms controlling the undrained shear strength behaviour of clays Can. Geotech. J. https://doi.org/10.1139/t99-071

MR Silveira 2021 Effect of polypropylene fibers on the shear strength–dilation behavior of compacted lateritic soils Sustain. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212603

AM Omar SS Agaiby MA Khouly 2024 Consolidation behavior and load transfer efficiency in a comparative study between stiffer and drained elements in soft clay Ain Shams Eng. J. 15 3 102500 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102500

MCH Sonnekus JV Smith 2022 Comparing shear strength dispersion characteristics of the triaxial and direct shear methods for undisturbed dense sand KSCE J. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-022-0040-6

F Zhao Y Zheng 2022 Shear strength behavior of fiber-reinforced soil: experimental investigation and prediction model Int. J. Geomech. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gm.1943-5622.0002502

MSI Zaini M Hasan S Almuaythir M Hyodo 2024 Experimental study on the use of polyoxymethylene plastic waste as a granular column to improve the strength of soft clay soil Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73224-y

MSI Zaini M Hasan S Almuaythir 2024 Experimental investigations on physico-mechanical properties of kaolinite clay soil stabilized at optimum silica fume content using clamshell ash and lime Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61854-1

Y Watabe K Udaka Y Nakatani S Leroueil 2012 Long-term consolidation behavior interpreted with isotache concept for worldwide clays Soils Found. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2012.05.005

J Yin K Zhang W Geng A Gaamom J Xiao 2021 Effect of initial water content on undrained shear strength of K0 consolidated clay Soils Found. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2021.08.010

S Almuaythir MSI Zaini M Hasan 2025 Stabilization of expansive clay soil using shells based agricultural waste ash Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94980-5

MSI Zaini M Hasan AR Suwito M Hyodo 2025 Influence of cockle shell ash and lime on geotechnical properties of expansive clay soil stabilized at optimum silica fume content Mater. Sci. Forum. https://doi.org/10.4028/p-G0rfq9

MSI Zaini M Hasan S Almuaythir MF Zolkepli 2025 Effect of silica fume, eggshell ash and lime on the strength of stabilized expansive clay soil Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-6072-8_3

Nik Aziz, N. N. A., Hasan, M., Zaini, M. S. I., Mohamed, S. N. A. & Winter, M. J. Hydrated Lime and Cockle Shell Ash: A Sustainable Approach to Soft Kaolin Clay Improvement. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Mech. https://doi.org/10.37934/aram.138.1.2745 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through the project number (PSAU/2024/01/28928)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sultan Almuaythir, Muhammad Syamsul Imran Zaini, & Muzamir Hasan, contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almuaythir, S., Zaini, M.S.I. & Hasan, M. Shear strength, compressibility, and consolidation behaviour of expansive clay soil stabilized with lime and silica fume. Sci Rep 15, 26185 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10642-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10642-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Performance evaluation of weak kaolin soils with waste-derived plastic granular inclusions

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Mechanistic and comparative laboratory assessment of lime dosage and uniaxial geogrid on the strength and durability of classified lateritic subgrade

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Mechanical and Microstructural Behavior of Clay Soil Stabilized with Metallic Tailing Powder

Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (2025)

-

Strength Improvement and Crack Mitigation in Clay Soil Using Basalt Fiber and Pozzolanic Additives

Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (2025)