Abstract

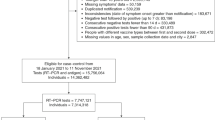

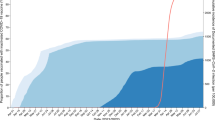

Currently approved vaccines have shown wide ranges of estimated efficacy. Despite the well-known benefits of inactivated virus vaccines, little information on their effectiveness has been robustly provided to monitor their specific impact. A stepped-wedge trial is an approach for assessing vaccine effectiveness and indirect protection in the real world. By the end of the study, all participants can receive the intervention, eliminating the ethical dilemma of placebo, especially during a pandemic. The aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of an inactivated COVID-19 vaccine in a massive urban population during the uncontrolled COVID-19 epidemic. We evaluated the long-term vaccine effectiveness (VE) of CoronaVac in Serrana, Brazil, using a stepped-wedge randomised trial. An indirect effect was also inferred from the temporal association between increasing vaccine coverage and the concurrent decline in SARS-CoV-2 incidence among participants who were not yet fully vaccinated. The city was divided into 25 subareas, clustered into four groups, and randomised to receive CoronaVac in a two-dose scheme. After 6 months, a booster dose was offered by the Brazilian Immunization Program. Participants were followed for one year, divided into four periods: February–May 2021; May–August 2021; August–November 2021; November 2021–February 2022. Vaccination occurred between February 14 and April 11, 2021. Up to 27,390 participants received the CoronaVac first dose, corresponding to 82.8% of the adult urban population. In the 1st period, overall VE was 52.8% (95% CI, 44.7 to 59.7) for preventing symptomatic COVID-19 and direct VE was 81.6% (95% CI, 76.4 to 85.6). When approximately 50% of the adult population was fully vaccinated, a reduction in symptomatic COVID-19 was also observed among participants who were not yet fully vaccinated, suggesting an indirect protective effect. Two-dose VE for COVID-19-related hospitalisation and death was 89.2% (95% CI, 68.1 to 96.3), 86.8% (95% CI, 72.2 to 93.7), 85.2% (95% CI, 66.1 to 93.6), 80.4% (95% CI, 47.6 to 92.7) in each period, respectively. The booster dose increased VE to 94.9% (95% CI, 59.1 to 99.4) and 84.1% (95% CI, 64.1 to 92.9) in the 3rd and 4th periods, respectively. CoronaVac induced long-term protection for severe cases. Unvaccinated individuals benefited from high vaccine coverage levels.

Trial registration: https://ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04747821).

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data and study materials are available from the corresponding author, Dr. Marcos Borges (marcosborges@fmrp.usp.br) upon reasonable request. Viral variant sequences analysed during the current study are available in the GISAID repository, https://gisaid.org/hcov-19-variants-dashboard/.

References

Lurie, N., Keusch, G. T. & Dzau, V. J. Urgent lessons from COVID 19: why the world needs a standing, coordinated system and sustainable financing for global research and development. Lancet 397 (10280), 1229–1236 (2021).

Palacios, R. et al. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of treating healthcare professionals with the adsorbed COVID-19 (inactivated) vaccine manufactured by sinovac - PROFISCOV: A structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 21 (1), 853 (2020).

Tanriover, M. D. et al. Efficacy and safety of an inactivated whole-virion SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac): interim results of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial in Turkey. Lancet 398 (10296), 213–222 (2021).

Polack, F. P. et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 (27), 2603–2615 (2020).

Control ECfDPa. Efficacy, effectiveness and safety of EU/EEA-authorised vaccines against COVID-19: living systematic review 2024. https://covid19-vaccines-efficacy.ecdc.europa.eu/.

Jara, A. et al. Effectiveness of an Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in Chile. N. Engl. J. Med. 385 (10), 875–884 (2021).

Russell, R. L., Pelka, P. & Mark, B. L. Frontrunners in the race to develop a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Can. J. Microbiol. 67 (3), 189–212 (2021).

Hodgson, S. H. et al. What defines an efficacious COVID-19 vaccine? A review of the challenges assessing the clinical efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21 (2), e26–e35 (2021).

Teerawattananon, Y. et al. A systematic review of methodological approaches for evaluating real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: Advising resource-constrained settings. PLoS ONE 17 (1), e0261930 (2022).

Xu, S. et al. Real-world effectiveness and factors associated with effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. BMC Med. 21 (1), 160 (2023).

The Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study. The gambia hepatitis study group. Cancer Res. 47 (21), 5782–5787 (1987).

Bellan, S. E. et al. Statistical power and validity of Ebola vaccine trials in Sierra Leone: a simulation study of trial design and analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 15 (6), 703–710 (2015).

Doussau, A. & Grady, C. Deciphering assumptions about stepped wedge designs: the case of Ebola vaccine research. J. Med. Ethics 42 (12), 797–804 (2016).

Hemming, K., Haines, T. P., Chilton, P. J., Girling, A. J. & Lilford, R. J. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ 350, h391 (2015).

Mascarenhas, J. & Kumar, P. D. P. Participatory mapping and modelling users’ notes. PLA Notes 12, 9–20 (1991).

Ferreira, N. N. et al. The impact of an enhanced health surveillance system for COVID-19 management in Serrana, Brazil. Public Health Pract. (Oxf.) 4, 100301 (2022).

Halloran, M. E., Longini, I. M. Jr. & Struchiner, C. J. Design and interpretation of vaccine field studies. Epidemiol. Rev. 21 (1), 73–88 (1999).

Wilder-Smith, A. et al. The public health value of vaccines beyond efficacy: methods, measures and outcomes. BMC Med. 15 (1), 138 (2017).

Panozzo, C. A. et al. Direct, indirect, total, and overall effectiveness of the rotavirus vaccines for the prevention of gastroenteritis hospitalizations in privately insured US children, 2007–2010. Am J Epidemiol. 179 (7), 895–909 (2014).

Wu, N. et al. Long-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against infections, hospitalisations, and mortality in adults: findings from a rapid living systematic evidence synthesis and meta-analysis up to December, 2022. Lancet Respir. Med. 11 (5), 439–452 (2023).

Link-Gelles, R. et al. Estimated 2023–2024 COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in adults. JAMA Netw. Open 8 (6), e2517402 (2025).

Ranzani, O. T. et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated Covid-19 vaccine with homologous and heterologous boosters against Omicron in Brazil. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 5536 (2022).

Chemaitelly, H. et al. Long-term COVID-19 booster effectiveness by infection history and clinical vulnerability and immune imprinting: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23 (7), 816–827 (2023).

Bodner, K., Irvine, M. A., Kwong, J. C. & Mishra, S. Observed negative vaccine effectiveness could be the canary in the coal mine for biases in observational COVID-19 studies. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 131, 111–114 (2023).

Andeweg, S. P. et al. Protection of COVID-19 vaccination and previous infection against Omicron BA.1, BA.2 and Delta SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 4738 (2022).

Andrews, N. et al. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron (B11529) variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 386 (16), 1532–1546 (2022).

Buchan, S. A. et al. Estimated effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccines against Omicron or delta symptomatic infection and severe outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open 5 (9), e2232760 (2022).

Cerqueira-Silva, T. et al. Duration of protection of CoronaVac plus heterologous BNT162b2 booster in the Omicron period in Brazil. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 4154 (2022).

Huang, Z. Y. et al. Effectiveness of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines among older adults in Shanghai: retrospective cohort study. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 77 (2023).

Huang, Z. Y. et al. Effectiveness of inactivated and Ad5-nCoV COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA. 2 variant infection, severe illness, and death. Bmc Med. 20 (1), 400 (2022).

McMenamin, M. E. et al. Vaccine effectiveness of one, two, and three doses of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac against COVID-19 in Hong Kong: a population-based observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22 (10), 1435–1443 (2022).

Eichner, M., Schwehm, M., Eichner, L. & Gerlier, L. Direct and indirect effects of influenza vaccination. BMC Infect. Dis. 17 (1), 308 (2017).

Kwok, K. O., Lai, F., Wei, W. I., Wong, S. Y. S. & Tang, J. W. T. Herd immunity - estimating the level required to halt the COVID-19 epidemics in affected countries. J. Infect. 80 (6), e32–e33 (2020).

Goldblatt, D. SARS-CoV-2: from herd immunity to hybrid immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22 (6), 333–334 (2022).

Palacios, R. Forgotten, but not forgiven: facing immunization challenges in the 21 (st) century. Colomb. Med. (Cali). 49 (3), 189–192 (2018).

Kennedy-Shaffer, L. & Lipsitch, M. Statistical properties of stepped wedge cluster-randomized trials in infectious disease outbreaks. Am. J. Epidemiol. 189 (11), 1324–1332 (2020).

Hemming, K. & Taljaard, M. Reflection on modern methods: when is a stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial a good study design choice?. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49 (3), 1043–1052 (2020).

Volpe, G. J. et al. Antibody response dynamics to CoronaVac vaccine and booster immunization in adults and the elderly: A long-term, longitudinal prospective study. IJID Reg. 7, 222–229 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was only possible thanks to the extraordinary commitment of people linked to several organisations. Instituto Butantan staff left their families and worked full-time in Serrana during the immunisation period to monitor, coordinate and support the vaccination centres (Andressa Freitas da Silva, Andressa Gabriela Moura de Oliveira, Arlete Sandra de Jesus, Auricélia Quirino Sousa, Ayla Sol Agassi Guimarães, Bruna Colli Moreira, Elis Regina Alves Pinto, Fábia Luzia Cestari, Gabrielle Maria Cordeiro Mongs, Juliana Araujo, Juliana Cassano Carvalhal, Juliana Souza Nakandakare, Lucimar Pereira de Souza, Patricia Teraza Bastos Pereira, Quetura Oliveira Silva, Renan Moreira dos Santos, Renata Carina dos Santos Giacon, Sharon Guedes Ferreira, Vanessa Evelin Jesus Vilches Sant´anna). Such dedication was vital for the study’s success. The authors are in debt to Juliana Araújo and her team in Human Resources, Romulo Xavier de Souza and his Central Warehouse team, and Vivian Retz and her Communication team at Butantan for their active involvement in the study since the very beginning. Other Instituto Butantan departments provided invaluable support to the study, and we are very grateful to the Administrative, Logistics, Laboratory, and Computer Service Centre staff (Julio Cesar Ciqueira Catani, Cláudia Anania Santos da Silva, Gabriela Mauric Frossard Ribeiro, Kilmary Lincolins de Oliveira Sequeira, Richard Rodrigues dos Santos, Gabriela Ribeiro, Alex Ranieri Jerônimo Lima, Maria da Graça Salomão, Mauricio Cesar Sampaio Ando, Lais Braga Soares, Hugo Alberto Brango, Elizabeth González Patiño, Ana Paula Batista, Gilberto Guedes de Padua, Joane do Prado Santos, Ricardo Haddad, and Roberta de Oliveira Piorelli). The Serrana State Hospital was the foundation for this study and we thank all the staff, especially Eduardo Lopes Seixas, Anderson Mendonça Jabur, Manuela de Paula Pereira and Maria Aline Sprioli. The work from CDHU and Diagonal staff was the basis of our in-depth knowledge of the Serrana territory (Ricardo de Almeida Nobre, Maristela Valenciano Achilles, and Shirley Andreatta). We want to emphasise and recognize the availability to provide help from the Municipal and State authorities, particularly in the Health and Education areas. We want to underscore the engagement of Serrana mayors, Leonardo Caressato Capitelli and Valerio Galante, and Health Secretaries, Leila Gusmão and José Carlos Moura, and the local officers. Moreover, the commitment of community and religious leaders to promote the study in the population was outstanding. Finally, we want to praise the people of Serrana who embraced the study and joined with the research team to resolve the scientific aims of Projeto S.

Funding

The study was supported by the Fundação Butantan, a non-profit foundation supporting activities of the Instituto Butantan, a public health research institution of the Government of São Paulo State, and by the Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP, grant 2020/10127-1). The vaccine manufacturer, Sinovac Life Sciences, had no role in the study but provided the product at no cost.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RP conceived this study. MCB, MTRPC, GJV, NNF, PMMG, MAALSA, EMJ, and DTC contributed to the trial design and protocol. MCB is the principal investigator, performed research, and coordinated the study. MCB drafted the manuscript. CFSLD, BBMG, BMC, GJV, NNF, and PMMG coordinated the study. CFSLD, BBMG, BMC, MCB, GJV, GRM, NNF, and PMMG were involved in the acquisition of data. MCB, RP, MTRPC, BMC, CFSLD, BBMG, GRM, GJV, NNF, PMMG, SCSV, SKH, BALF, RTC, DTC, EJFP, PEB, LR, JIDF, MAL, LBOA, JCVT, SCSV, DTC, MAALSA, EMJ, FCB contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. MCB, RP, MTRPC, BMC, CFSLD, BBMG, GRM, GJV, NNF, PMMG, SCSV, SKH, BALF, RTC, DTC, EJFP, PEB, LR, JIDF, MAL, LBOA, JCVT, SCSV, DTC, MAALSA, EMJ, FCB edited the manuscript. PEB, LR, JIDF, MAL, LBOA, JCVT, performed the statistical analysis. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors had full access to all data in the studies and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MCB, BMC, BBMG, CFSLD, GJV, NNF, PMMG, BALF, and RTC received research funding from Butantan Institute during the conduct of this study. RP, MTRPC, and DTC were employees of Butantan Institute during the conduct of this study. EJFP, PEB, LR, JIDF, MAL, LBOA, JCVT, SCSV, DTC, MAALSA, EMJ, and FCB are employees of Butantan Institute. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Hospital, Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo (CAAE 42390621.1.0000.5440). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 1975 and subsequently amended. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borges, M.C., Palacios, R., Conde, M.T.R.P. et al. Indirect protection and long-term effectiveness of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: a stepped-wedge randomised trial in Serrana, Brazil. Sci Rep (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37815-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37815-1