Abstract

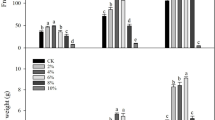

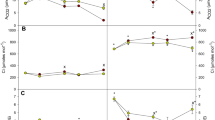

Protein from duckweed (Araceae, subfamily Lemnoideae) grown on diluted animal slurries for nutrient upcycling could potentially replace plant-derived feed proteins which would be more efficiently used as human food. However, little information is available on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from slurry-grown duckweed, and previous studies have not reported methane emissions from a similar system. Here, we report on GHG (methane, carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide) and ammonia emissions from duckweed grown on diluted cattle slurry measured in daylight and darkness, compared with emissions from diluted slurry without duckweed. We observed (i) initially high but rapidly declining methane emissions, independent of lighting or treatment, (ii) a net carbon dioxide fixation by duckweed, independent of lighting, (iii) high nitrous oxide emissions, independent of lighting, and (iv) a > 80% reduction of ammonia emissions by duckweed, independent of lighting. Our data shows potential of duckweed protein as a sustainable protein with 3.54 to 6.54 CO2eq kg− 1 protein, compared to faba bean (3.61 kg CO2eq kg− 1 protein) or barley protein (5.35 CO2eq kg− 1 protein). But despite the potential of slurry-grown duckweed as sustainable protein source, swapping ammonia volatilization for nitrous oxide emissions represents a limitation of the current system and mitigation strategies are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All relevant data is available in the manuscript, tables and figures.

References

Richardson, K. et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh2458. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adh2458 (2023).

Broucek, J. Production of methane emissions from ruminant husbandry: A review. J. Environ. Prot. 5, 1482–1493 (2014).

Amon, B., Kryvoruchko, V., Amon, T. & Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Methane, nitrous oxide and ammonia emissions during storage and after application of dairy cattle slurry and influence of slurry treatment. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 112, 153–162 (2006).

Kupper, T. et al. Ammonia and greenhouse gas emissions from slurry storage–A review. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 300, 106963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.106963 (2020).

Skinner, C. et al. The impact of long-term organic farming on soil-derived greenhouse gas emissions. Sci. Rep. 9, 1702. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38207-w (2019).

Pikaar, I. et al. Microbes and the next nitrogen revolution. Env. Sci. Technol. 51, 7297–7303 (2017).

Libutti, A. & Monteleone, M. Soil vs. groundwater: The quality dilemma. Managing nitrogen leaching and salinity control under irrigated agriculture in Mediterranean conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 186, 40–50 (2017).

Padilla, F. M., Gallardo, M. & Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Global trends in nitrate leaching research in the 1960–2017 period. Sci. Total Environ. 643, 400–413 (2018).

Smith, K. A. Changing views of nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural soil: key controlling processes and assessment at different spatial scales. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 68, 137–155 (2017).

Leip, A. et al. Impacts of European livestock production: Nitrogen, sulphur, phosphorous, greenhouse gas emissions, land-use, water eutrophication and biodiversity. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 115004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/115004 (2015).

Oron, G., Porath, D. & Jansen, H. Performance of the duckweed species Lemna gibba on municipal wastewater for effluent renovation and protein production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 29, 258–268 (1987).

Xu, J., Cheng, J. J. & Stomp, A.-M. Growing Spirodela polyrrhiza in swine wastewater for the production of animal feed and fuel ethanol: A pilot study. CLEAN - Soil Air Water 40, 760–765 (2012).

Appenroth, K.-J. et al. Nutritional value of duckweeds (Lemnaceae) as human food. Food Chem. 217, 266–273 (2017).

Leger, D. et al. Photovoltaic-driven microbial protein production can use land and sunlight more efficiently than conventional crops. PNAS 118, e2015025118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015025118 (2021).

Stadtlander, T., Förster, S., Rosskothen, D. & Leiber, F. Slurry-grown duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza) as a means to recycle nitrogen into feed for rainbow trout fry. J. Clean. Prod. 228, 86–93 (2019).

Stadtlander, T. et al. Dilution rates of cattle slurry affect ammonia uptake and protein production of duckweed grown in recirculating systems. J. Clean. Prod. 357, 131916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131916 (2022).

Rojas, O. J., Liu, Y. & Stein, H. H. Concentration of metabolizable energy and digestibility of energy, phosphorus, and amino acids in lemna protein concentrate fed to growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 92, 5222–5229 (2014).

Haustein, A. T. et al. Performance of broiler chickens fed diets containing duckweed (Lemna gibba). J. Agric. Sci. 122, 285–289 (1994).

Anderson, K. E., Lowman, Z., Stomp, A.-M. & Chang, J. Duckweed as a feed ingredient in laying hen diets and its effect on egg production and composition. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 10, 4–7 (2011).

Zetina-Córdoba, P. et al. Effect of cutting interval of Taiwan grass (Pennisetum purpureum) and partial substitution with duckweed (Lemna sp and Spirodela sp) on intake, digestibility and ruminal fermentation of Pelibuey lambs. Livest. Sci. 157, 471–477 (2013).

Fiordelmondo, E. et al. Effects of partial substitution of conventional protein sources with duckweed (Lemna minor) meal in the feeding of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) on growth performances and the quality product. Plants 11, 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11091220 (2022).

Stadtlander, T. et al. Partial replacement of fishmeal with duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza) in feed for two carnivorous fish species, Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquac. Res. 2023, 1–15 (2023).

Fasakin, E. A., Balogun, A. M. & Fasuru, B. E. Use of duckweed, Spirodela polyrrhiza L. Schleiden, as a protein feedstuff in practical diets for tilapia Oreochromis niloticus L. Aquac. Res. 30, 313–318 (1999).

de Matos, F. T. et al. Duckweed bioconversion and fish production in treated domestic wastewater. J. Appl. Aquac. 26, 49–59 (2014).

Bairagi, A., Sarkar Ghosh, K., Sen, S. K. & Ray, A. K. Duckweed (Lemna polyrhiza) leaf meal as a source of feedstuff in formulated diets for rohu (Labeo rohita Ham) fingerlings after fermentation with a fish intestinal bacterium. Bioresour. Technol. 85, 17–24 (2002).

Shrivastav, A. K. Effect of greater duckweed Spirodela polyrhiza supplemented feed on growth performance, digestive enzymes, amino and fatty acid profiles, and expression of genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis of juvenile common carp Cyprinus carpio. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 788455. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.788455 (2022).

Appenroth, K.-J. et al. Nutritional value of the Duckweed species of the genus Wolffia (Lemnaceae) as human food. Front. Chem. 6, 483. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2018.00483 (2018).

Parnian, A., Chorom, M., Jaafarzadeh, N. & Dinarvand, M. Use of two aquatic macrophytes for the removal of heavy metals from synthetic medium. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 16, 194–200 (2016).

Iatrou, E. I., Stasinakis, A. S. & Aloupi, M. Cultivating duckweed Lemna minor in urine and treated domestic wastewater for simultaneous biomass production and removal of nutrients and antimicrobials. Ecol. Eng. 84, 632–639 (2015).

Baccio, D. D. et al. Response of Lemna gibba L. to high and environmentally relevant concentrations of ibuprofen: Removal, metabolism and morpho-physiological traits for biomonitoring of emerging contaminants. Sci. Total Environ. 584–585, 363–373 (2017).

Cui, W. & Cheng, J. J. Growing duckweed for biofuel production: a review. Plant Biol. 17, 16–23 (2015).

Verma, R. & Suthar, S. Utility of duckweeds as source of biomass energy: A review. Bioenerg. Res. 8, 1589–1597 (2015).

Acosta, K. et al. Source of Vitamin B12 in plants of the Lemnaceae family and its production by duckweed-associated bacteria. J. Food Compos. Anal. 135, 106603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2024.106603 (2024).

Jones, G., Scullion, J., Dalesman, S., Robson, P. & Gwynn-Jones, D. Acidification increases efficiency of Lemna minor N and P recovery from diluted cattle slurry. Clean. Waste Syst. 6, 100122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clwas.2023.100122 (2023a).

Jones, G., Scullion, J., Dalesman, S., Robson, P. & Gwynn-Jones, D. Lowering pH enables duckweed (Lemna minor L.) growth on toxic concentrations of high-nutrient agricultural wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 395, 136392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136392 (2023b).

Mohedano, R. A., Tonon, G., Costa, R. H. R., Pelissari, C. & Filho, P. B. Does duckweed ponds used for wastewater treatment emit or sequester greenhouse gases?. Sci. Total Environ. 691, 1043–1050 (2019).

Silva, J. P., José, L. R., Miguel, R. P., Lubberding, H. & Gijzen, H. Influence of photoperiod on carbon dioxide and methane emissions from two pilot-scale stabilization ponds. Water Sci. Technol. 66, 1930–1940 (2012).

Sims, A., Gajaraj, S. & Hu, Z. Nutrient removal and greenhouse gas emissions in duckweed treatment ponds. Water Res. 47, 1390–1398 (2013).

Dai, J., Zhang, C., Lin, C.-H. & Hu, Z. Emission of carbon dioxide and methane from duckweed ponds for stormwater treatment. Water Environ. Res. https://doi.org/10.2175/106143015X14362865226310 (2015).

Rabaey, J. & Cotner, J. Pond greenhouse gas emissions controlled by duckweed coverage. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 889289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.889289 (2022).

Devlamynck, R. et al. Agronomic and environmental performance of Lemna minor cultivated on agricultural wastewater streams—A practical approach. Sustainability 13, 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031570 (2021).

Mestayer, C. R., Culley, D. D. Jr., Standifer, L. C. & Koonce, K. L. Solar energy conversion efficiency and growth aspects of the duckweed, Spirodela punctata (G. F. W. Mey.) Thompson. Aquat. Bot. 19, 157–170 (1984).

Ziegler, P., Adelmann, K., Zimmer, S., Schmidt, C. & Appenroth, K.-J. Relative in vitro growth rates of duckweeds (Lemnaceae) – the most rapidly growing higher plants. Plant Biol. 17, 33–41 (2014).

Stadtlander, T., Schmidtke, A., Baki, C. & Leiber, F. Duckweed production on diluted chicken manure. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 33, 128–138 (2023).

Prosser, J. I. Autotrophic nitrification in bacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 30, 125–177 (1989).

Lekang, O.-I. Aquaculture Engineering (ed Lekang, O.-I.) (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

Cedergreen, N. & Madsen, T. V. Nitrogen uptake by the floating macrophyte Lemna minor. New Phytol. 155, 285–292 (2002).

Yang, Y. et al. Measuring field ammonia emissions and canopy ammonia fluxes in agriculture using portable ammonia detector method. J. Clean. Prod. 216, 542–551 (2019).

Yao, Y. et al. Duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza) as green manure for increasing yield and reducing nitrogen loss in rice production. Field Crops Res. 214, 273–282 (2017).

Sun, H. et al. Floating duckweed mitigated ammonia volatilization and increased grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency of rice in biochar amended paddy soils. Chemosphere 237, 124532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124532 (2019).

Hernandez, M. E. & Mitch, W. J. Influence of hydrologic pulses, flooding frequency, and vegetation on nitrous oxide emission from created riparian marshes. Wetlands 26, 862–877 (2006).

Ugetti, E., García, J., Lind, S. E., Martikainen, P. J. & Ferrer, I. Quantification of greenhouse gas emissions from sludge treatment wetlands. Water Res. 46, 1755–1762 (2012).

Ma, Y.-Y., Tong, C., Wang, W.-Q. & Zeng, C.-S. Effect of azolla on CH4 and N2O emissions in Fuzhou plain paddy fields. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 20, 723–727 (2012).

Kimani, S. M. et al. Azolla cover significantly decreased CH4 but not N2O emissions from flooding rice paddy to atmosphere. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 64, 68–76 (2018).

Gonzalez, A. D., Frostell, B. & Carlsson-Kanyama, A. Protein efficiency per unit energy and per unit greenhouse gas emissions: Potential contribution of diet choices to climate change mitigation. Food Policy 36, 562–570 (2011).

Braglia, L. et al. New insights into interspecific hybridization in Lemna L. Sect. Lemna (Lemnaceae Martinov). Plants 10, 2767. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10122767 (2021).

Wang, C. Simultaneous analysis of greenhouse gases by gas chromatography. Agilent Technologies, accessible at: https://www.chem-agilent.com/pdf/5990-5129EN.pdf (2010).

Fuss, R. & Hueppi, R. Greenhouse gas flux calculation from chamber measurements. Accessible at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gasfluxes/gasfluxes.pdf (2020).

Hüppi, R. et al. Restricting the nonlinearity parameter in soil greenhouse gas flux calculation for more reliable flux estimates. PLoS ONE 13, e0200876. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200876 (2018).

Lee, H. & Romero, J. IPCC Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero) (IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2023) 35–115 https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Mercator Foundation Switzerland and the Vontobel Foundation for their financial support for this study. Furthermore, we thank Dr. Laura Morello and her team for identifying the utilized duckweed species as Lemna minor. And finally, for his effort to bring light into the O2 mystery in the slurry-duckweed system, we would like to thank Jakob Zopfi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S.: Design of study, data acquisition, data analysis, writing of manuscript, revision of manuscript. D.M.G.: Design of study, data acquisition, data analysis. R.M.: Design of study, data acquisition, data analysis. C.B.: Data acquisition. N.B.: Design of study, revision of manuscript. F.L.: writing of manuscript, revision of manuscript. H.M.K.: data analysis, writing of manuscript, revision of manuscript. L.A.: Design of study, data acquisition, data analysis, writing of manuscript, revision of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of plant material procurement

Since Lemna minor is endemic to Switzerland and is not a protected species (IUCN status: least concern) and it is naturally growing on our own institute’s premises in rainwater ponds, it is not subject to any type of permission process (e.g. such as the Nagoya protocol) necessary for this type of research project. No voucher specimen has been deposited in a publicly available herbarium.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stadtlander, T., Gomez, D.M., Müller, R. et al. Greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions from duckweed cultivation systems using diluted liquid manure. Sci Rep (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-39270-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-39270-4