Abstract

In recent years, scholars have extensively investigated the correlation between childhood trauma and cyberbullying. However, findings in this area have been inconsistent. The current study employed a meta-analysis method to explore the relationship between childhood trauma and cyberbullying among students in mainland China, aiming to establish a reliable foundation for resolving existing controversies on this matter. This study included 26 articles, encompassing a total of 29,389 subjects. The findings revealed a moderate positive correlation between childhood trauma and cyberbullying (r = 0.418, 95%CI [0.335, 0.495]). Firstly, the correlation was affected by regions. Compared with eastern China, cyberbullying in the central and western regions was more likely to be affected by childhood trauma (rEastern < rCenter < rWestern). Secondly, the childhood trauma scale could moderate this correlation (rCPANS < rCPMSs < rCTQ-SF), showing the highest correlation coefficient when the CTQ-SF was used as a tool to measure childhood trauma. Thirdly, age also significantly influenced the relationship between childhood trauma and cyberbullying. The correlation coefficient among young adults was higher than that of adolescents (rAdolescents < rYoung adults). Lastly, gender differences were found to significantly moderate the relationship between childhood trauma and cyberbullying, indicating a higher correlation coefficient in female than male (P < 0.05).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the Digital 2022 report, 63.1% of the world’s population (5.03 billion people) are Internet users (Locowise, 2022). Nowadays, people use Internet for instant communication, mobile live broadcasting, and viewing videos, which transcends numerous geographical and temporal constraints, thereby enhancing communication and cooperation among individuals. However, the Internet is akin to a double-edged sword. Despite its evident advantages, it also harbors numerous issues, including harassing calls and messages, abuse or threats and so on (Aricak, 2009), namely Cyberbullying (CB). Alternative terms for similar phenomena include Online Bullying (Dong, 2020) and Online Aggressive Behavior (Lu et al., 2019). Earlier years, Olweus (1994) defined bullying as the repeated aggression by an individual or group against another individual who is unable to defend themselves. While CB serves as the extension of traditional bullying on the Internet, which refers to the prolonged aggressive behavior of individuals or groups using electronic communication platforms against individuals who are not able to protect themselves (Smith et al., 2008). CB mainly includes offending others by electronic means, posting or sharing others’ privacy without others’ permission, spreading rumors, sending threatening messages and malicious clips (Hogan and Strasburger, 2020). It is characterized by anonymity, repeatability, lack of restrictions on space or time, and lack of monitoring of electronic media (Kowalski and Limber, 2007; Mehari et al. 2014).

Research indicated that the prevalence of CB behavior among university students was about 60%, with 20% of students acknowledging that they had engaged in bullying others at least once during Internet use, and more than half of students reporting experiencing CB at least once (Gahagan et al., 2016). Some scholars conducted a cyberbullying survey involving over 1,400 middle school students, revealing that 30% of the students admitted to engaging in CB, while more than half reported experiencing CB (Zhou et al., 2013). People who have suffered from CB often present personality disorders, diminished self-esteem, and increased tendency to commit suicide; Meanwhile, perpetrators of CB are at risk of crossing legal boundaries (Kowalski et al., 2014). Hence, the effective control and reduction of CB have become shared concerns within society.

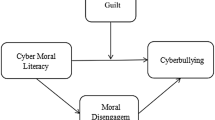

A study found that CB in adulthood is related to Childhood Trauma (CT), such as adverse childhood experience (Felitti et al., 1998) and childhood maltreatment (Li et al., 2022), and CT is recognized as one of the risk factors for CB in adolescents and adulthood (Kircaburun et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019a). CT is a phenomenon experienced under the age of 18 that significantly impacts the physical and mental health of individuals, primarily encompassing sexual abuse, physical abuse and neglect, emotional abuse and neglect, and other forms of injury (World Health Organization, 2022). At present, scholars have conducted a large number of studies on the relationship between CT and CB (e.g., Chen and Zhu, 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Among them, some scholars believe that there is a significant positive correlation between CT and CB, indicating that individuals who have experienced trauma in childhood are more prone to exhibiting aggressive behavior in virtual spaces as they grow up (e.g., Emirtekin et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a). According to Social Learning Theory (SLT), children acquire social behavior in their daily lives by observing and imitating the actions of role models (Bandura, 2001). A positive parent-child relationship fosters the development of self-control, social skills, and enhances mental health. Conversely, an adverse parent-child relationship may result in children experiencing diminished self-worth, emotional instability, difficulties in communicating, aggressive behavior, and other related issues. In other words, victims who have experienced parental abuse in childhood are more likely to imitate their parents’ aggressive behavior and more likely to become perpetrators when they grow up (Wilson et al., 2009). Moreover, the methods and habits parents employ in managing relationships can further influence children’s cognitive construction of CB (Dodge et al., 1990). In addition, according to Attachment Theory (Bowlby, 1982), children who consistently receive care and responsive interactions from their parents are inclined to develop a positive orientation towards interpersonal relationships in the future (Bergersen and Varma, 2020). On the contrary, if children experience abuse or neglect in their formative years, they are likely to develop insecure attachments and exhibit more hostile behavior during interactions with others (Levy and Blatt, 1999).

However, some scholars found a weak correlation between the two (Saltz et al., 2020; Wang, 2021), which might be explained by Social Support and Computer-mediated Communication Theory (Wright et al., 2003) that demonstrates that the existence of social interaction depends on the shared characteristics of individuals in the computer media environment, thus making the social relationships closer (Wright et al., 2003). In other words, utilizing the Internet can offer social support, aiding individuals in stress relief and emotional restoration. The Internet serves as a platform for groups sharing similar CT experiences, enabling them to offer mutual social support and encouragement, alleviate negative emotions (e.g., depression, anxiety, self-blame, and low confidence/esteem), and reduce accordingly psychological problems caused by CT (Wilson and Scarpa, 2014), thereby reducing the likelihood that they will engage in CB (Skilbred-Fjeld, et al., 2020).

In summary, research findings regarding the correlation between CT and CB were inconsistent, calling for an application of a meta-analysis method to offer a comprehensive perspective for exploring the relationship between them. In addition, this study assumed that the relationship between CT and CB might be influenced by the measurement tools and the demographic variables, such as region, age, gender, and year. The rationale is discussed below.

Measures of childhood trauma and cyberbullying as moderators

The first to follow the term CB of children is the Canadian teacher Bill Belsey, who created a website focused on CB of children (www.cyberbullying.ca) (Belsey, 2005). As research on CB deepens, scholars have turned their attention to CB assessment tools. For instance, Erdur-Baker and Kavúut (2007) compiled a network bullying scale called Cyberbullying Inventory (CBI). The CBI comprises two subscales: one assesses the behavior of bullying others in the online environment, while the other evaluates and analyzes the experience of being bullied by others. In 2010, Topcu and Erdur-Baker (2010) revised the CBI to be a Revised Cyber Bullying Inventory (RCBI), which consists of 28 items. In addition to developing the English version of CBI, scholars have developed versions of other languages, such as the Chinese version of CBI with 18 entries examining cyberbullying perpetration developed by Zhou et al. (2013). Additionally, Patchin and Hinduja (2015) have compiled a Cyberbullying Crime Scale (CBOS). CBOS includes five dimensions: physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and sexual abuse (Emirtekin et al., 2020).

Research on CT dates back to the 1960s, when they began to focus on child abuse by Kempe et al. (1962). With the deepening of CT research, various testing tools have emerged. For example, the highest cited scale is Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein et al., 1994). It contains 70 items and four dimensions: physical and emotional abuse, emotional neglect, sexual abuse, and physical neglect, which can fully measure a person’s experience of abuse during his/her early childhood. Later, to screen out the history of abuse in the clinical population in a short time and to reduce the burden of over-response, Bernstein and colleagues (2003) adjusted the original questionnaire into a short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF). It consists of 28 items and five dimensions: physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect and sexual abuse. CTQ-SF is widely used by scholars and has been adapted into various language versions, such as the Chinese version of the CTQ-SF (Zhao et al., 2005). What’s more, some researchers compiled a Child Psychological Abuse and Neglect Scale (CPANS) based on the cultural background of mainland China (Deng et al., 2007). This scale comprises two subscales: psychological abuse and psychological neglect. The psychological abuse subscale encompasses intimidation, interference, and scolding, while the neglect subscale includes emotional neglect, educational neglect, and physical neglect. After that, Wright et al. (2015) developed a cyberbullying perpetration scale (CPS) with 9 items, which was also widely used to test how often participants perpetrate cyberbullying.

Using different measurement tools to explore the relationship between CT and CB may cause a certain degree of bias because different measurement tools have different theoretical bases and dimensions. Thus, the measurement tool is further analyzed as a moderate variable affecting the correlation between CT and CB.

Demographic variables as moderators

It is necessary to consider the moderator role of the region in the relationship between CT and CB. Chinese mainland can be divided into three regions: eastern, central and western regions (Lei and Cui, 2016). Due to the differences in economic resources (Fryers et al., 2005), the average socioeconomic status in eastern China is relatively high. With the development of the economy, the mental health of teenagers and adults may also be improved, and the level of network literacy will be generally high in eastern China. In contrast, the central and western regions are relatively backward, and the young people’s network literacy is depressed (Fang et al., 2023). Therefore, this study hypothesized that the relationship between CT and CB is significantly different among different regions.

It is also necessary to consider the moderator role of gender in the relationship between CT and CB. In terms of bullying, according to evolutionary psychology (Wang et al., 2016), violence and aggression can confer greater survival and reproductive advantages to men, making them more prone to engage in bullying compared to women. In contrast, females exhibit a greater inclination towards harmonious interactions and are more prone to cultivate positive relationships, even in the aftermath of childhood trauma (Wang et al., 2021). That means relationship between CT and CB may be stronger in boys than girls (Fang et al., 2020). Therefore, this paper assumed that the relationship between CT and CB is influenced by an individual’s gender.

It is also necessary to consider the moderator role of age. Previous studies have found a low positive correlation between CT and CB in younger people (Saltz et al., 2020); However, some other studies have found that there was a moderate positive correlation between CT and CB among young adults (Emirtekin et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2023). Therefore, this paper assumed that the relationship between CT and CB varies significantly among different ages.

In addition to the above variables, changes in year may also influence the relationship between CT and CB. Some studies showed that the correlation between CT and CB intensifies with increasing years (Wang et al., 2019a; Burcu et al., 2021; Akarsu et al., 2022). Contrarily, other studies indicated that the correlation between CT and CB decreased with increasing years (Emirtekin et al., 2020; Burcu et al., 2021; Fang et al., 2022).Therefore, this paper assumed that the relationship between CT and CB is significantly influenced by the year.

To conclude, this paper employed a meta-analysis approach to investigate the relationship between CT and CB and its moderators, focusing on Chinese mainland young adults and adolescents as the study sample. It tried to find answers to the following questions: (1) What is the effect size and direction between CT and CB? (2) Will the study characteristics (measurement tool, region, gender, age, year) affect the relationship between CT and CB?

Research method

Literature search

We searched databases: CNKI, Wanfang Data, Chongqing VIP Information Co., Ltd. (VIP), Baidu Scholar, ProQuest dissertations, Web of Science, Google Scholar, EBSCO and PsyclNFO. The relevant studies on CT and CB conducted between January 2012 and September 2023 were searched. The main search terms for CB were “Cyberbullying” “Cyberattack” “Online Bullying” “Cyberbullying Perpetration” “Cyberbullying Perpetration Attitudes”. A Boolean operator “OR”was used among them. The main search terms of CT were “Childhood Trauma” “Childhood Trauma Experiences” “Childhood Maltreatment” “Childhood Emotional Trauma” “Early Life Trauma” “Emotional Abuse” “Psychological Maltreatment” “Psychological Abuse” “Sexual Abuse”. Also, a Boolean operator “OR”was used among them. In addition, a Boolean operator “AND” was utilized to connect the terms for CT and CB.

The meta-analysis closely followed the protocols outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). PRISMA provides specific recommendations for conducting a comprehensive and effective meta-analysis. Inclusion criteria in this study were as follows : (1) CT and CB were measured simultaneously, and the papers clearly reported the Pearson’s product-moment coefficients or r, or T and F values that could be converted into r values; (2) The sample size was clearly reported; (3) The subject group was normal people in the Chinese mainland area, while abnormal groups such as disease and crime were excluded; (4) The data involved in the literature could not be repeated. If two or more papers were published with the same data, only the data of one of them would be kept. Papers without data or clear sample size and the repeated publications were excluded. Finally, 26 papers met the selection criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (see Fig. 1).

Coding Variables

The collected literature characteristics were coded, including author information (year of publication), source of publication, region, age, sample size, correlation coefficient between CT and CB, measurement tool, and percentage of female (see Table 1). Regarding coding age, it should be noted that not every included article reported the age of the subjects, but they all reported the stages of the subjects’ schools (primary school, junior high school, senior high school, undergraduate) (e.g., Song et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022; Yao, 2022). Thus, we decide to categorize them according to subjects’ school stage. As we know, different countries and cultures have distinct definitions of adolescent/adult age groups (Sawyer et al., 2018). Since this study was conducted in the context of China, the age classification would be based on Chinese laws, research, or customs. According to China’s nine-year compulsory education regulations, the age of starting primary school is 6 years old. Then, the age for primary school is about 6–12 years old, the age for junior high school and senior high school is around 13–18 years old, and the age for undergraduates is usually 19–22 years old. The Civil Code of China stipulates that anyone over the age of 18 is considered an adult (Article 17). Therefore, this study coded undergraduates as young adults. Secondly, no law in China stipulates the starting age for adolescents. The most commonly used standard is from the World Health Organization (2024), which states that adolescence starts at around 10 years old. Thus, this study coded the student population in junior and senior high schools as adolescents. Only one article includes primary and high schools (Chen and Zhu, 2023), which we coded as mixed.

The extraction of effect size followed the principles: (1) The correlation between CT and CB was encoded; (2) Independent samples were coded once, or we only once encoded if multiple independent samples were reported in the same article at the same time; (3) When calculating the effect size for each category, there was no overlapping data we used in. Each raw data appeared only once under each category to make sure the independence of the effect value calculation.

Quality assessment of included studies

Literature quality evaluation was performed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tool (Moola et al., 2017). The checklist comprises eight items, each assessed as “Yes,” “No,” “Unclear,” or “Not applicable.”. 2 points were assigned for the “Yes” option, 1 point for “Unclear,” and 0 points for “No” or “Not applicable,” resulting in a minimum score of 0 and a total possible score of 16 points. The quality evaluation process were conducted independently by two researchers. In case of any disagreement, a consensus was reached through discussion with a third higher-class researcher. Consequently, all 26 studies included in the meta analysis scored above 11 points, with 22 out of them surpassing a score of 15, indicative of higher quality. The quality assessment undertaken here is not employed for the exclusion of any articles; rather, it serves as a perspective for discussing the reliability and quality of the research.

Effect size calculation

The meta-analysis method of correlation coefficient was used in this study (Borenstein et al., 2009). This means that we used the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient r as the calculated data for the effect value. We calculated the weight and 95% confidence interval, got the result of the r values transformed by Fisher Z. Conversion formula: Zr = 0.5 * ln [(1 + r) / (1 - r)], VZ = 1 / n-3, SEz = sqrt (1 / n - 3) (VZ is the variance and SEz is the standard error).

Data processing and analysis

We used the meta-analysis software CMA 3.0 to analyze the data.To make each study estimate representative of the full effect size, heterogeneity testing is necessary. First of all, the homogeneity test provides a basis for whether the outcome adopts a fixed effect model or a random effect model. The fixed effect model was chosen if the test results show that the effect values were homogeneous. Secondly, the homogeneity test also provides a basis for the analysis of moderating effects. The higher statistically significant heterogeneity indicated the existence of the moderating effects (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001).

Results

Effect size and homogeneity tests

The present meta-analysis included 26 articles, compromising 29389subjects. At the same time, the homogeneity test related to CT and CB in 26 independent samples, with Q stats of 1735.646, p < 0.001, I2 = 98.560, indicating that included literature was heterogeneous. This may be due to the different sample sizes, different measurement tools, or different sources of subjects used in the literature. That is, there may be a moderate effect. Due to the high heterogeneity of the collected literature, random models were chosen for analysis using the method provided by Lipsey and Wilson (2001).

Using random models to analyze the correlation between CT and CB, we found that the correlation between them was statistically significant, with a correlation coefficient of 0.418, 95%CI [0.335, 0.495]. The Z-value of the CT and CB relationship was 9.011, p < 0.001, which indicated that the association of CT and CB is stable (see Table 2).

Moderator analysis

As stated above, random effects models should also be used in intermediary effect analysis. Meta-ANOVA analysis is suitable for the analyzing the regulatory effects of classified variables, such as regional differences, type of measurement tool. However, meta-regression analysis is ideal for the analyzing regulatory effects of continuous variables (the proportion of year and females).

Meta-ANOVA analysis

To deeply analyze the moderating effects of the relationship between CT and CB, Meta-ANOVA analysis was used to analyze the moderating effects of categorical variables (see Table 3).

The data analysis showed a significant moderation of the relationship between CT and CB. Regarding region, the homogeneity test (Q = 272.297, df = 4, P < 0.001) showed that region had a moderating effect on this correlation. The correlation coefficients between CT and CB in the eastern, central and western subjects were respectively 0.398 (95% CI = [0.247, 0.531]), 0.407 (95% CI = [0.286, 0.515]), and 0.860 (95% CI = [0.831, 0.884]), namely rEastern < rCenter < rWestern. For age, the homogeneity test (Q = 11.893, df = 2, P < 0.01) showed that grade had a moderating effect on this correlation. The correlation coefficients between CT and CB of young adults and adolescents were respectively 0.571 (95% CI = [0.425, 0.688]) and 0.310 (95% CI = [0.269, 0.350]), namely rAdolescents < rYoung adults. For CT scale, the homogeneity test (Q = 286.528, df = 3, P < 0.001) showed that CT scale regulated this correlation. The correlation coefficients between CT and CB of CTQ-SF, CPMS and CPANS subjects were respectively 0.439 (95% CI = [0.282, 0.573]), 0.364 (95% CI = [0.315, 0.411]), and 0.311(95% CI = [. 254, 0.365]), namely rCPANS < rCPMSs < rCTQ-SF. For CB scale, the homogeneity test (Q = 3.345, df = 3, P > 0.05) showed insignificant moderation.

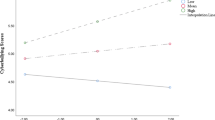

Meta-regression analysis

To test whether continuous variables (gender and year) modulated the effect size between CT and PIU, the r effect size was returned to the female percentage and publication year in each sample. Meta-regression results (QModel[1, k = 26] = 5.88, P < 0.05) demonstrated that the relation between CT and CB was moderated by gender. Specifically, as the number of female increases, the correlation coefficient between CT and CB also increases. However, the other meta-regression results (QModel[1, k=26] = 1.99, P > 0.05) demonstrated that the relation between CT and CB was not moderated by year (see Table 4).

Publication bias

We drew a funnel plot to check whether the results were biased due to effect sizes from different sources (Fig. 2). The results showed that 26 effects were symmetrically distributed and size averaged. In addition, Egger’s regression analysis (Egger et al. 1997) was conducted on CT and CB, and no publication bias appeared (t(24) = 0.760, P > 0.05). To further test for publication bias, this study calculated that the Z = 70.990 (P < 0.001) of Classic Fail-safe N. The inclusion of 4083 missed studies made the analysis result not significant statistically (Rosenthal, 1979). Hence, this study was less susceptible to publication bias, indicating a relatively stable relationship between CT and CB.

Discussion

The results of the meta-analysis showed a moderate positive correlation between CT and CB, which is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Emirtekin et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020b), indicating that students experiencing CT are more likely to perpetrate CB. In accordance with Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 2001), observing suboptimal parent-child relationships renders children susceptible to the adoption of bullying behaviors. Children who have experienced such environments since childhood find it easier to internalize the concept of violent behavior, leading to a certain degree of psychological harm, affecting the normal development of personality, and thus increasing their likelihood of bullying others in real or online environments (Wilson et al., 2009). The General Strain Theory (Agnew, 1992) also believes that if individuals in the growing environment do not meet their expectations, but experience all kinds of pressure and stimulation (such as in the family, abuse or indifference, etc.), they will become irritable and anxious. Experience negative emotions and pressure may prompt young people to be deviant, such as bullying others to eliminate their negative emotions, and participating in bullying enhances presence and satisfaction (Hinduja and Patchin, 1998). Besides, insecure attachment relationships can serve as additional triggers for CB. According to Attachment Theory (Bowlby, 1982), abuse in childhood can undermine the secure attachment relationships between the children and their parents. The adverse parent-child relationship can lead children to perceive a lack of recognition and love, consequently heightening a range of potential risks in their interpersonal communication processes (Crittenden and Ainsworth, 1989). What’s more, the finding is also in line with the Psychoanalytic Theory (Freud, 1998) arguing that the emotional abuse and neglect that individuals suffered in childhood may make them unable to express their feelings in a normal way. As a result, individuals may resort to employing defense mechanisms to restore inner equilibrium, which may hinder them from adjusting their psychological state timely, potentially leading to anxiety or even aggressive behaviors (Wang et al., 2019b).

The results also showed that region modulated the relationship between CT and CB. Specifically, the correlation in eastern regions was lower than that in the central and western regions of Chinese mainland. It can be explained for the following reasons: First, this phenomenon may be influenced by variations in the extent of network monitoring across different regions. Compared with non-coastal areas, the Internet infrastructure in the eastern coastal areas is more developed (Wang and Jin, 2002). The presence of advanced network video surveillance equipment and technology has contributed to a reduction in the incidence of cyberbullying, thereby regulating the relationship between CT and CB. Second, it may be correlated with the varying levels of mental health development across different regions. In contrast to the eastern regions, the central and western regions exhibited delayed economic development, coupled with a relatively recent initiation of mental health education (Cheng, 2010), which may affect the monitoring and intervention level of CT and CB, and then adjust the relationship between CT and CB.

Age also moderates the relationship between CT and CB. Specifically, the most pronounced effect on the relationship was observed within the young adults, followed by the adolescents. The reasons may be: First, concerning the accessibility of social software on the Internet, the registration and usage time of minors will be regulated to a certain extent (Traş and Öztemel, 2019). Upon becoming adults and entering university, individuals distance themselves from the family environment and emancipate themselves from such constraints, gaining more unrestricted access to their leisure time (Bulcroft et al., 1996), which potentially increases the likelihood of engaging in CB. Second, regarding the scope of network communication, young adults exhibit a broader communication reach, with a communication circle characterized by greater heterogeneity compared to the younger individuals (Buglass et al., 2017). Such exposure enables them to browse and access a wide array of information. Consequently, this may enhance opportunities for CB, thereby affecting the correlation coefficient between CT and CB.

The CT measurement modulates the relationship between CT and CB. Specifically, it had the highest effect on CTQ-SF, followed by CPMS and then CPANS. The CTQ-SF questionnaire was comprehensive and accurate, encompassing not only emotional aspects but also physical and sexual dimensions. It has also been translated into many languages, and the Chinese version compiled by Zhao Xingfu and colleagues (2005) is the most commonly used questionnaire by Chinese mainland scholars. The CPMS was evolved based on the CPANS, mainly focusing on the psychological content. Compared with CTQ-SF, the measurement range of CPMS and CPANS is narrow. The information will inevitably be omitted, and the accuracy may be not as high as CTQ-SF.

Gender also moderates the relationship between CT and CB, showing that girls who experienced CT are more likely than boys to perpetrate CB (e.g., Hébert, et al., 2016; MacMillan, et al., 2001). This is inconsistent with our previous research hypothesis. It may be explained by following reasons: On the one hand, although both boys and girls are negatively affected by CT (Gallo et al., 2018), such adverse impacts of CT will diminish over time for boys but not girls (Godinet et al., 2014). For females, the adverse reactions of psychological and physical symptoms caused by CT may intensify and last a long time (Spertus et al., 2003). Thus, the impact of traumatic experiences on girls enhances the strength of the correlation between CT and CB. On the other hand, influenced by stressful life events (e.g., CT), women are more prone to experiencing psychological problems (e.g., mood disorders) than men (Akbaba et al., 2015). Thus, the frequency of CB tends to increase as these psychological problems become more serious.

Limitations and for future studies

Egger’s publication bias test was used for the results of the meta-analysis. The results showed that the included studies did not show any significant publication bias and had stable results from the meta-analysis. It also showed that the results of this study are more realistic and representative than those of a single sample. However, our study still has some limitations. (1)The study’s sample comprises only students. To enhance the generalizability of research findings, future studies may consider incorporating a more diverse sample group, encompassing individuals from various professional backgrounds in society. (2) Due to the limited language skills of the authors, only articles published in English and Chinese were selected. Thus, in the process of collecting data, we may miss some valuable information in other languages. (3) Only the moderating effects of region, measurement instrument, publication year, gender and age were tested in this study. Some latent moderator variables, such as family situation, parenting styles and interpersonal adaptation could be tested in future research.

Conclusion

Using a meta-analysis of data comprising 29389 Chinese mainland students across 26 articles, we found a moderate positive correlation between CT and CB. Meanwhile, the relationship between the two was moderated by region, age, measurement tool, and gender. Specifically, the relationship between CT and CB was modulated by region, showing the correlation coefficient between CT and CB in the central and western regions was higher than that in the eastern regions. The relationship between CT and CB was also regulated by age. The correlation coefficient between CT and CB of young adults was higher than that of adolescents. Furthermore, the relationship between CT and CB was moderated by CT measurement tools. When the CTQ-SF was used as a tool to measure CT, the correlation coefficient between CT and CB was higher than the other tools. In addition, the relationship between CT and CB was modulated by gender. The correlation between CT and CB was more pronounced in females than in males.

References

*Studies included in the meta-analysis

Agnew R (1992) Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminol 30:47–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-014-9198-2

Akarsu Ö, Budak Mİ, Okanlı A (2022) The relationship of childhood trauma with cyberbullying and cyber victimization among university students. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 41:181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2022.06.004

Akbaba Turkoglu S, Essizoglu A, Kosger F, Aksaray G (2015) Relationship between dysfunctional attitudes and childhood traumas in women with depression. Int J Soc Psychiatry 61:796–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764015585328

Arıcak OT (2009) Psychiatric symptomatology as a predictor of cyberbullying among university students. EJER 34:167–184

Bandura A (2001) Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 52:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Belsey B (2005) Cyberbullying: An emerging threat to the “always on” generation. Recuperado el 5:2010

Bergersen BT, Varma P (2020) The influence of attachment styles on cyberbullying experiences among university students in Thailand, mediated by sense of Belonging: a path model. Scholar Hum Sci 12:299–321

Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J (1994) Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [Database record]. https://doi.org/10.1037/t02080-000

Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Zule W (2003) Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus Negl 27:169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR (2009) Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley Press, New York, USA, 10.1002/9780470743386

Bowlby J (1982) Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. Am J Orthopsychiatry 52:664–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x

Buglass SL, Binder JF, Betts LR, Underwood JD (2017) Motivators of online vulnerability: The impact of social network site use and FOMO. Comput Hum Behav 66:248–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.055

Bulcroft RA, Carmody DC, Bulcroft KA (1996) Patterns of parental independence giving to adolescents: Variations by race, age, and gender of child. J Marriage Fam 866-883. https://doi.org/10.2307/353976

Burcu TÜRK, Yayak A, Hamzaoğlu N (2021) The effects of childhood trauma experiences and attachment styles on cyberbullying and victimization among university students. Kıbrıs Türk. Psikiyatr ve Psikol Derg 3:241–249. https://doi.org/10.35365/ctjpp.21.4.25

*Chen L, Wang YL, Li Y (2020) Belief in a Just World and Trait Gratitude Mediate the Effect of Childhood Psychological Maltreatment on Undergraduates Cyberbullying Attitude [In Chinese]. Chin J Clin Psychol 28:152–156. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.01.032

*Chen Q, Zhu Y (2023) Experiences of childhood trauma and cyberbullying perpetration among adolescents in China. Asia Pac J Soc Work 33:50–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2022.2077816

*Chen XS (2019) Research on the Current Situation and Relationship of Childhood Psychological Abuse, Cyber Bullying, Self-esteem and Coping Style of Middle School Students [In Chinese]. Dissertation, Yunnan Normal University

Cheng YS(2010) An Investigation into the Current Situation of Mental Health Education in Primary and Secondary Schools of Zhejiang Province [In Chinese]. Chin J Special Edu 13:81–86

Crittenden PM, Ainsworth MD (1989) 14 child maltreatment and attachment theory. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V (ed) Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. Cambridge University Press, London, p 432–463

Deng YL, Pan C, Tang QP, Yuan XH, Xiao CG (2007) Development of child psychological abuse and neglect scale. Chin J Behav Med Sci 16:175–7. https://doi.org/10.3760/CMA.J.ISSN.1005-8559.2007.02.036

Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS (1990) Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science 250:1678–1683. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2270481

Dong YH (2020) The Relationship of Offline Victimization and Online Bullying: Mediating Role of Anger Rumination [In Chinese]. J Schooling Stud 17:19–25

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J 315:629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Emirtekin E, Balta S, Kircaburun K, Griffiths MD (2020) Childhood emotional abuse and cyberbullying perpetration among adolescents: The mediating role of trait mindfulness. Int J Ment Health Addiction 18:1548–1559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-0055-5

Erdur-Baker Ö, Kavúut F (2007) A new face of peer bullying: cyberbullying. Eurasia J Educ Res 27:31–42

*Fang J, Lai X, Luo WW (2020) Moderating Effects of Callous-Unemotional Traits and Gender on the Relationship between Maltreatment and Cyberbullying in Adolescents [In Chinese]. Chin J Clinl Psychol 28:991-994. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.05.027

*Fang J, Wang W, Gao L, Yang J, Wang X, Wang P, Wen Z (2022) Childhood maltreatment and adolescent cyberbullying perpetration: a moderated mediation model of callous—unemotional traits and perceived social support. J Interpers Violence 37:5026–5049. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520960106

Fang Z, Qi X, Yuan Y, Qin Y, Liu C (2023) Review of research on Internet literacy in 2022. J Edu Media Stud 23–28. https://doi.org/10.19400/j.cnki.cn10-1407/g2.2023.01.022

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 14:245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Freud S (1998) New introductory lectures on psychoanalysis. Crown Publishing Group, Taipei, Chinese edition

Fryers T, Melzer D, Jenkins R, Brugha T (2005) The distribution of the common mental disorders: social inequalities in Europe. Clin Pr Epidemiol Ment Health 1:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-1-14

Gahagan K, Vaterlaus JM, Frost LR (2016) College student cyberbullying on social networking sites: Conceptualization, prevalence, and perceived bystander responsibility. Comput Hum Behav 55:1097–1105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.019

Gallo EAG, Munhoz TN, deMola CL, Murray J (2018) Gender differences in the effects of childhood maltreatment on adult depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abus Negl 79:107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.003

Godinet MT, Li F, Berg T (2014) Early childhood maltreatment and trajectories of behavioral problems: Exploring gender and racial differences. Child Abus Negl 38:544–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.018

*Gao Y (2018) The relationship between psychological maltreatment and neglect and rural adolescents’cyberbullying behaviors:The mediating effect of moral disengagement [In Chinese]. Dissertation, Shenzhen University

Hébert M, Cénat JM, Blais M, Lavoie F, Guerrier M (2016) Child sexual abuse, bullying, cyberbullying, and mental health problems among high schools students: a moderated mediated model. Depress Anxiety 33:623–629. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22504

Hinduja S, Patchin JW (1998) Cyberbullying research summary: Cyberbullying and strain. Educ Psychol 18:433–444

Hogan M, Strasburger V (2020) Twenty questions (and answers) about media violence and cyberbullying. Pediatr Clin North Am 67:275–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2019.12.002

*Jin T, Lu GZ, Zhang L, Fan GP, Li XX (2017) The Effect of Childhood Psychological Abuse on College Students’Cyberbullying: The Mediating Effect of Moral Disengagement [In Chinese]. Chin J Spec Edu 65-71

*Jin TL, Wu YT, Zhang L, Liu ZH (2020) Childhood Psychological Maltreatment and Cyberbullying among Chinese Adolescents: The moderating roles of Perceived Social Support and Gender. J Psychol Sci 43:323–332

Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, Droegemueller W, Silver HK (1962) The battered-child syndrome. JAMA 181:17–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1962.03050270019004

Kircaburun K, Demetrovics Z, Király O, Griffiths MD (2020) Childhood emotional trauma and cyberbullying perpetration among emerging adults: A multiple mediation model of the role of problematic social media use and psychopathology. Int J Ment Health Addiction 18:548–566

Kowalski RM, Limber SP (2007) Electronic bullying among middle school students. J Adolesc Health 41:22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.017

Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR (2014) Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol Bull 140:1073–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035618

Lei H, Cui Y (2016) Effects of academic emotions on achievement among mainland Chinese students: A meta-analysis. Soc Behav Pers Int J 44:1541–1553. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.9.1541

Levy KN, Blatt SJ (1999) Attachment theory and psychoanalysis: Further differentiation within insecure attachment patterns. Psychoanal Inq 19:541–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351699909534266

*Li M, He Q, Zhao J, Xu Z, Yang H (2022) The effects of childhood maltreatment on cyberbullying in college students: The roles of cognitive processes. Acta Psychol 226:103588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103588

Lipsey MW, Wilson DB (2001) Practical meta-analysis. Sage Publications, California

Locowise (2022) Digital 2022: July global statshot report. https://locowise.com/blog/digital-2022-april-global-statshot-report. Accessed 22 Apr 2022

Lu GZ, Jin TL, Ge J, Ren XH, Zhang Y, Jiang YZ (2019) The Effect of Violent Exposure on Online Aggressive Behavior of College Students: A Moderated Mediation. Psychol Dev Edu 35:360–367. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2019.03.14. Model [In Chinese]

MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, Lin E, Boyle MH, Jamieson E, Beardslee WR (2001) Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 158:1878–1883. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1878

Mehari KR, Farrell AD, Le ATH (2014) Cyberbullying among adolescents: Measures in search of a construct. Psychol Violence 4:399–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037521

*Meng J (2021) The influence of emotional abuse and neglect on cyberaggressive behavior among middle school students:a moderatedmediation model [In Chinese]. Dissertation, Zhengzhou University

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Lisy K, Mu PF (2017) Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris, E, Munn, Z (ed). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute

Olweus D (1994) Long-term outcomes for victims and an effective school-based intervention program. Aggressive Behav Curr Perspect 97-130

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Patchin JW, Hinduja S (2015) Measuring cyberbullying: Implications for research. Aggress Violent Beh 23:69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.013

*Qiao JS (2021) The Influence of Childhood Psychological Maltreatment on Adolescent Bullying[In Chinese]. Dissertation, Shanxi University https://doi.org/10.27284/d.cnki.gsxiu.2021.000974

Rosenthal R (1979) The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull 86:638. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638

Saltz SB, Rozon M, Pogge DL, Harvey PD (2020) Cyberbullying and its relationship to current symptoms and history of early life trauma: A study of adolescents in an acute inpatient psychiatric unit. J Clin Psychiatry 81:4003. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.18m12170

Silva S, Figueiredo P, Ramião E, Barroso R (2023) Childhood Trauma and Cyberbullying Perpetration: The Mediating Role of Callous-Unemotional Traits. Victims & Offenders 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2022.2126574

Skilbred-Fjeld S, Reme SE, Mossige S (2020) Cyberbullying involvement and mental health problems among late adolescents. Cyberpsychol J Psychosoc Res Cyberspace 14:5. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2020-1-5

Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N (2008) Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49:376–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC (2018) The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2:223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

*Song KL, Li S, Zhang XJ (2023) The influence of psychological neglect on cyberbullying: the moderating effect of self-esteem [In Chinese]. Psychologies Magazine 18:35–36. https://doi.org/10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2023.04.011

*Song YQ, Wang L, Ma ZF, Xue ZY, Li ZY, Cao XQ (2020) The mediating role of depression symptoms in childhood abuse and cyberbullying among college students [In Chinese]. Chin J Dis Control Prev 24:57–61. https://doi.org/10.16462/j.cnki.Zhjbkz.2020.01.012

Spertus IL, Yehuda R, Wong CM, Halligan S, Seremetis SV (2003) Childhood emotional abuse and neglect as predictors of psychological and physical symptoms in women presenting to a primary care practice. Child Abus Negl 27:1247–1258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.05.001

*Sun X, Chen L, Wang Y, Li Y (2020) The link between childhood psychological maltreatment and cyberbullying perpetration attitudes among undergraduates: Testing the risk and protective factors. PLoS One 15:e0236792. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236792

Topcu Ç, Erdur-Baker Ö (2010) The revised cyber bullying inventory (RCBI): Validity and reliability studies. Proc -Soc Behav Sci 5:660–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.161

Traş Z, Öztemel K (2019) Examining the relationships between Facebook intensity, fear of missing out, and smartphone addiction. Addicta 6:91–113. https://doi.org/10.15805/addicta.2019.6.1.0063

*Wang BC (2020) The Effect of Psychological Maltreatment on Cyberbullying in Middle School Students: The Mediating Effect of Negative Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategy and Dark Triad [In Chinese]. Dissertation, Beijing Forestry University

*Wang N (2021) The Influence of Childhood Maltreatment, Deviant peer affiliation on Adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration [In Chinese]. Dissertation, Shanxi University

Wang P, Wang X, Lei L (2021) Gender differences between student–student relationship and cyberbullying perpetration: An evolutionary perspective. J Interpers Violence 36:9187–9207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519865970

Wang R, Jin B (2002) Studies on the regional differences of the internet development in China. Hum Geogr 17:89–92. https://doi.org/10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2002.06.021

*Wang X, Dong W, Qiao J (2023) How is childhood psychological maltreatment related to adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration? The roles of moral disengagement and empathy. Curr Psychol 42:16484–16494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02495-9

Wang X, Lei L, Liu D, Hu H (2016) Moderating effects of moral reasoning and gender on the relation between moral disengagement and cyberbullying in adolescents. Pers Individ Differ 98:244–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.056

*Wang X, Yang J, Wang PLei L (2019a) Childhood maltreatment, moral disengagement, and adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration: Fathers’ and mothers’ moral disengagement as moderators. Compute Hum Behav 95:48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.031

Wang YL, Chen HL, Wang Y, Chen ZX (2019b) Relationship Between Childhood Abuse and Left-Behind Adolescents’ Cyberbullying: A Moderate Mediation Model [In Chinese]. J Hum First Norm U 19:42–46. https://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-DYHN201905009.htm

Wilson HW, Stover CS, Berkowitz SJ (2009) Research Review: The relationship between childhood violence exposure and juvenile antisocial behavior: a meta‐analytic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50:769–779. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01974.x

Wilson LC, Scarpa A (2014) Childhood abuse, perceived social support, and posttraumatic stress symptoms: A moderation model. Psych Trauma: Theory, Res, Pr, Policy 6:512–518. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032635

World Health Organization (2022) Child maltreatment. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment. Accessed 30 Sep 2023

World Health Organization (2024) Adolescent health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1. Accessed 20 Apr 2024

Wright MF, Aoyama I, Kamble S, Li Z, Soudi S, Lei L, Shu C (2015) Peer attachment and cyber aggression involvement among Chinese, Indian, and Japanese adolescents. Societies 5:339–353. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc5020339

Wright KB, Bell SB, Wright KB, Bell SB (2003) Health-related support groups on the Internet: Linking empirical findings to social support and computer-mediated communication theory. J Health Psychol 8:39–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105303008001429

*Wu JY, Zhang SS, Huo AQ (2022) Effects of psychological maltreatment on cyberbullying among rural left-behind junior high school students: the mediating role of teacher-student relationship and the moderating role of depression [In Chinese]. Psychol Mag 17:90–92. https://doi.org/10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2022.10.024

*Xu W, Zheng S (2022) Childhood emotional abuse and cyberbullying perpetration among Chinese university students: The chain mediating effects of self-esteem and problematic social media use. Front Psychol 13:1036128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1036128

*Yang J, Li W, Zhu YL, Tao Y (2022) Influence of childhood adversity on college students internet bullying behavior Chain mediating effect between personal pain and thick black personality tendency [In Chinese]. Chin J Health Psych 30:899–904. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2022.06.021

*Yao ZH (2022) A study on the relationship between childhood adverse experience and cyberbullying of college students and the intervention of meaning in life [In Chinese]. Dissertation, Southwest University

*Zhang H, Sun X, Chen L, Yang H, Wang Y (2020a) The mediation role of moral personality between childhood psychological abuse and cyberbullying perpetration attitudes of college students. Front Psychol 11:1215. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01215

*Zhang J (2022) The Relationship between Childhood Trauma and Adolescent Cyberbullying: the Mediation of Hostile Attribution Bias and the Moderation of Empathy [In Chinese]. Dissertation, Hubei University

*Zhang L, Liu LH, Jin TL, Jia YR (2017) Mediating effect of trait angeron relationship between childhood psychological maltreatment and online aggressive behavior in college students [In Chinese]. Chin Ment Health J 31:659–664. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2017.08.014

*Zhang Y, Zhang SS, Yuan B (2020b) A Study on the relationship Between Psychological Neglect, Teacher-studentRelationship and Cyberbulling among Junior High School Students [In Chinese]. J Jimei U (Edu Sci Ed) 21:60–65

Zhao XF, Zhang YL, Li LF, Zhou YF, Yang SC (2005) Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of childhood trauma questionnaire. Chin J Clin Rehabil 9:105–107. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1673-8225.2005.20.052

Zhou Z, Tang H, Tian Y, Wei H, Zhang F, Morrison CM (2013) Cyberbullying and its risk factors among Chinese high school students. Sch Psychol Int 34:630–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034313479692

Acknowledgements

This research was sponsored by the Project of Center for Higher Education Developmet Research in Xinjiang (ZK202336C), the Xinjiang Normal University Primary Discipline Project (23XJKD0206), and the Project of Center for Higher Education Developmet Research in Xinjiang (ZK202317C).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shunyu Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing - Review & Editing. Kelare Ainiwaer: Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Yuxuan Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing, Correspondence.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Ainiwaer, K. & Zhang, Y. The relationship between childhood trauma and cyberbullying: a meta-analysis of mainland Chinese adolescents and young adults. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 765 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03274-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03274-0

This article is cited by

-

Predicting cyber-harassment in the digital age: an integrated model of psychological, technological, and environmental factors using SEM

Iran Journal of Computer Science (2025)