Abstract

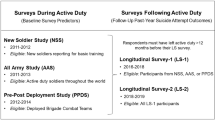

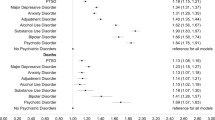

Military personnel are routinely involved in pandemic relief efforts, placing them at risk of increased exposure to pandemic-related stressors. Although ample research suggests that exposure to pandemic-related stressors contributed to decrements in mental health among civilians during the COVID-19 pandemic, limited work has examined whether these patterns were also salient in military populations. Here we report data on The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (STARRS) Longitudinal Study, which screened for 30-day prevalence of major depressive episode, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and panic attack among 10,206 US Army soldiers and veterans before (2018–2019) and then again during (2020–2022) the COVID-19 pandemic. Statistically significant increases were found in prevalence, with relative risk (RR) comparable to that observed in civilian samples (RR 1.28–1.40). The greatest increases were observed among women, Black and Hispanic individuals, those of lower socioeconomic status and Regular Army soldiers compared with reservists and those separated from service. Exposures to pandemic-related stressors, although associated with significantly increased mental health difficulty (RR 1.06–1.17), did not explain associations of sociodemographics and Army career characteristics with difficulty RR. No significant interactions were found between pandemic-related stressors and either baseline difficulty prevalence, sociodemographics or Army career characteristics predicting difficulty RR. Results suggest that military personnel may experience pandemic-related declines in mental health similar to those observed in civilian populations, with the largest changes occurring among individuals with greater socioeconomic vulnerability and/or higher exposure to pandemic-related stress. Findings emphasize the importance of ensuring accessibility to appropriate support for military personnel during pandemic conditions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$79.00 per year

only $6.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

STARRS-LS Wave 1, Wave 2 and Wave 3 data, as well as data from the earlier Army STARRS New Soldier Study, All Army Study and Pre and Post Deployment studies, are available through the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan (https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/studies/35197). STARRS-LS and Army STARRS data are restricted from general dissemination, meaning that a confidential data use agreement must be established before access. Researchers interested in gaining access to the data can submit their applications via ICPSR’s online Restricted Contracting System. Guidelines for applying for access to this data can be found under the data and documentation tab at the above URL. The STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study data are not available for public release.

Code availability

Code used to produce the statistical output is available via GitHub at https://github.com/kingme5005/COVID_ls2_ls3. Because the data used in this study are not publicly available and require DoD clearance to access, we cannot post the source code used to read in the Army administrative data (which requires DoD clearance) and create the 2,000+ variables used in this analysis.

References

Cavicchioli, M. et al. What will be the impact of the Covid-19 quarantine on psychological distress? Considerations based on a systematic review of pandemic outbreaks. Healthcare 9, 101 (2021).

Chu, I. Y., Alam, P., Larson, H. J. & Lin, L. Social consequences of mass quarantine during epidemics: a systematic review with implications for the COVID-19 response. J. Travel Med. 27, taaa192 (2020).

Shah, K. et al. Focus on mental health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: applying learnings from the past outbreaks. Cureus 12, e7405 (2020).

Goldmann, E. & Galea, S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu. Rev. Public Health 35, 169–183 (2014).

Galea, S., Merchant, R. M. & Lurie, N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern. Med. 180, 817–818 (2020).

Pfefferbaum, B. & North, C. S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 510–512 (2020).

Twenge, J. M. & Joiner, T. E. Mental distress among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Psychol. 76, 2170–2182 (2020).

Czeisler, M. et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020.Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69, 1049–1057 (2020).

Daly, M., Sutin, A. R. & Robinson, E. Depression reported by US adults in 2017–2018 and March and April 2020. J. Affect. Disord. 278, 131–135 (2021).

Ettman, C. K. et al. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2019686 (2020).

McGinty, E. E., Presskreischer, R., Han, H. & Barry, C. L. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA 324, 93–94 (2020).

Twenge, J. M., McAllister, C. & Joiner, T. E. Anxiety and depressive symptoms in U.S. Census Bureau assessments of adults: trends from 2019 to fall 2020 across demographic groups. J. Anxiety Disord. 83, 102455 (2021).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Estimated prevalence of and factors associated with clinically significant anxiety and depression among US adults during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2217223 (2022).

Blendermann, M., Ebalu, T. I., Obisie-Orlu, I. C., Fried, E. I. & Hallion, L. S. A narrative systematic review of changes in mental health symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 54, 43–66 (2024).

Robinson, E., Sutin, A. R., Daly, M. & Jones, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J. Affect. Disord. 296, 567–576 (2022).

Santomauro, D. F. et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398, 1700–1712 (2021).

Sun, Y. et al. Comparison of mental health symptoms before and during the covid-19 pandemic: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 134 cohorts. Br. Med. J. 380, e074224 (2023).

Witteveen, A. B. et al. COVID-19 and common mental health symptoms in the early phase of the pandemic: an umbrella review of the evidence. PLoS Med. 20, e1004206 (2023).

Bonanno, G. A., Brewin, C. R., Kaniasty, K. & Greca, A. M. Weighing the costs of disaster: consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 11, 1–49 (2010).

North, C. S. & Pfefferbaum, B. Mental health response to community disasters: a systematic review. JAMA 310, 507–518 (2013).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Changes in prevalence of mental illness among US adults during compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 45, 1–28 (2022).

Yavorsky, J. E., Qian, Y. & Sargent, A. C. in Working in America (ed. Wharton, A.) 305–317 (Routledge, 2022).

Hagerty, S. L. & Williams, L. M. Moral injury, traumatic stress, and threats to core human needs in health-care workers: the COVID-19 pandemic as a dehumanizing experience. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 10, 1060–1082 (2022).

Magesh, S. et al. Disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2134147 (2021).

ElTohamy, A. et al. Testing positive, losing a loved one, and financial hardship: real-world impacts of COVID-19 on US college student distress. J. Affect. Disord. 314, 357–364 (2022).

Coley, R. L., Carey, N., Baum, C. F. & Hawkins, S. S. COVID-19-related stressors and mental health disorders among US adults. Public Health Rep. 137, 1217–1226 (2022).

Kapucu, N. The role of the military in disaster response in the US. Eur. J. Econ. Pol. Stud. 4, 7–33 (2011).

Davis, T. et al. Quantitative analysis of United States National Guard COVID-19 disaster relief activities April–June 2020. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 17, e562 (2023).

Powell, T., Billiot, S., Muller, J., Elzey, K. & Brandon, A. The cost of caring: psychological adjustment of health-care volunteers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Traumatology 28, 383 (2022).

Baker, M. D., Southard, M. A., Beymer, M. R. & Riviere, L. A. National Guard service members decedent recovery and processing operations during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Mil. Psychol. 35, 431–439 (2023).

Gomez, S. A. Q. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on army families: household finances, familial experiences, and soldiers’ behavioral health. Mil. Psychol. 35, 420–430 (2023).

Mitchell, N. A., McCauley, M., O’Brien, D. & Wilson, C. E. Mental health and resilience in the Irish defense forces during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Mil. Psychol. 35, 383–393 (2023).

Fischer, I. C., Na, P. J., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Krystal, J. H. & Pietrzak, R. H. Characterization of mental health in US Veterans before, during, and 2 years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e230463 (2023).

Hill, M. L. et al. Mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in U.S. military veterans: a population-based, prospective cohort study. Psychol. Med. 53, 945–956 (2023).

Marquardt, C. A. et al. Evaluating resilience in response to COVID-19 pandemic stressors among veteran mental health outpatients. J. Psychopathol Clin. Sci. 132, 26–37 (2023).

Na, P. J. et al. military veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationally representative, prospective cohort study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 151, 546–553 (2022).

McCaslin, S. E., Bramlett, D., Juhasz, K., Mackintosh, M. & Springer, S. in Positive Psychological Approaches to Disaster (ed. Schulenberg, S. E.) 61–79 (Springer, 2020).

Ursano, R. J. et al. The Army study to assess risk and resilience in servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry 77, 107–119 (2014).

Avdiu, B. & Nayyar, G. When face-to-face interactions become an occupational hazard: jobs in the time of COVID-19. Econ. Lett. 197, 109648 (2020).

Burch, A. E. & Jacobs, M. COVID-19, police violence, and educational disruption: the differential experience of anxiety for racial and ethnic households. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 9, 2533–2550 (2022).

Thomeer, M. B., Moody, M. D. & Yahirun, J. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 10, 961–976 (2023).

Cretney, R. M. Local responses to disaster: the value of community led post disaster response action in a resilience framework. Disaster Prev. Manage. 25, 27–40 (2016).

Jacobs, G. A., Gray, B. L., Erickson, S. E., Gonzalez, E. D. & Quevillon, R. P. Disaster mental health and community-based psychological first aid: concepts and education/training. J. Clin. Psychol. 72, 1307–1317 (2016).

Southwick, S. M., Satodiya, R. & Pietrzak, R. H. Disaster mental health and positive psychology: an afterward to the special issue. J. Clin. Psychol. 72, 1364–1368 (2016).

Mancini, A. D. When acute adversity improves psychological health: a social-contextual framework. Psychol. Rev. 126, 486–505 (2019).

Mancini, A. D., Westphal, M. & Griffin, P. Outside the eye of the storm: can moderate hurricane exposure improve social, psychological, and attachment functioning? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 47, 1722–1734 (2021).

Salanti, G. et al. Changes in the prevalence of mental health problems during the first year of the pandemic: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. BMJ Ment. Health 27, e301018 (2024).

Al Maqbali, M., Alsayed, A., Hughes, C., Hacker, E. & Dickens, G. L. Stress, anxiety, depression and sleep disturbance among healthcare professional during the COVID-19 pandemic: an umbrella review of 72 meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 19, e0302597 (2024).

Donnelly, W. M. et al. The United States Army and the Covid-19 Pandemic (United States Army, 2021); https://history.army.mil/Publications/Publications-Catalog/The-United-States-Army-and-the-COVID-19-Pandemic/

Naifeh, J. A. et al. The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS): progress toward understanding suicide among soldiers. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 34–48 (2019).

Heeringa, S. G. et al. Field procedures in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 22, 276–287 (2013).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Design of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 22, 267–275 (2013).

Stanley, I. H. et al. Predicting suicide attempts among U.S. Army soldiers after leaving active duty using information available before leaving active duty: Results from the Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers-Longitudinal Study (STARRS-LS). Mol. Psychiatry 27, 1631–1639 (2022).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Response bias, weighting adjustments, and design effects in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 22, 288–302 (2013).

Kessler, R. C. & Ustün, T. B. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13, 93–121 (2004).

Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K. & Domino, J. L. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress 28, 489–498 (2015).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Clinical reappraisal of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Screening Scales (CIDI-SC) in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 22, 303–321 (2013).

Holmberg, M. J. & Andersen, L. W. Estimating risk ratios and risk differences: alternatives to odds ratios. JAMA 324, 1098–1099 (2020).

Marginal Means, Adjusted Predictions, and Marginal Effects (STATACorp, 2022); https://www.stata.com/features/overview/marginal-analysis/

Benjamini, Y. & Yekutieli, D. False discovery rate–adjusted multiple confidence intervals for selected parameters. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 100, 71–81 (2005).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61, 344–349 (2008).

SAS ®Software 9.4 (SAS Institute, 2013).

Acknowledgements

The Army STARRS Team consists of Co-Principal Investigators: R.J.U. (Uniformed Services University) and M.B.S. (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System). Site Principal Investigators: J.R.W. (University of Michigan) and R.C.K. (Harvard Medical School). Army scientific consultant/liaison: K. Cox (Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Manpower and Reserve Affairs). Other team members: P. A. Aliaga (Uniformed Services University); D. M. Benedek (Uniformed Services University); L. Campbell-Sills (University of California San Diego); C. S. Fullerton (Uniformed Services University); N. Gebler (University of Michigan); M. House (University of Michigan); P. E. Hurwitz (Uniformed Services University); S. Jain (University of California San Diego); T.-C. Kao (Uniformed Services University); L. Lewandowski-Romps (University of Michigan); A. Luedtke (University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center); H. Herberman Mash (Uniformed Services University); J. A. Naifeh (Uniformed Services University); M. K. Nock (Harvard University); N. Hani Zainal (Harvard Medical School); N.A.S. (Harvard Medical School); and A. M. Zaslavsky (Harvard Medical School). Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number U01MH087981 (2009–2015) with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Subsequently, STARRS-LS was sponsored and funded by the Department of Defense (USUHS grant number HU0001-15-2-0004). E.R.E. was supported in part by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service (CSR&D) VA-STARRS Researcher-in-Residence Program (Project SPR-002-24F). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIMH, the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense or the Department of Veteran Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C.K. and A.M.M.-B.: concept and design. R.C.K., A.M.M.-B., E.R.E., A.J.K., H.L., M.V.P., N.A.S., H.N.Z., J.R.W., M.B.S. and R.J.U.: acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data. R.C.K., A.M.M.-B. and E.R.E.: drafting of the manuscript. A.J.K., H.L. and M.V.P.: statistical analysis. R.C.K., M.B.S. and R.J.U.: obtained funding. R.C.K., A.M.M.-B., S.M.G., N.A.S., J.R.W., M.B.S. and R.J.U.: technical, administrative or material support. R.C.K., A.M.M.-B. and N.A.S.: supervision. All authors: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

In the past 3 years, R.C.K. was a consultant for Cambridge Health Alliance, Canandaigua VA Medical Center, Child Mind Institute, Holmusk, Massachusetts General Hospital, Partners Healthcare, Inc., RallyPoint Networks, Inc., Sage Therapeutics and University of North Carolina. He has stock options in Cerebral Inc., Mirah, PYM (Prepare Your Mind), Roga Sciences and Verisense Health. In the past 3 years, M.B.S. received consulting income from Actelion, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Aptinyx, atai Life Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bionomics, BioXcel Therapeutics, Clexio, EmpowerPharm, Engrail Therapeutics, GW Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Roche/Genentech. He has stock options in Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals and EpiVario. He is paid for his editorial work on Biological Psychiatry (Deputy Editor) and UpToDate (Co-Editor-in-Chief for Psychiatry). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks Sebastian Trautmann and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–4.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kessler, R.C., Millikan-Bell, A.M., Edwards, E.R. et al. Effects of pandemic-related stressors on anxiety and mood difficulty during versus before the COVID-19 pandemic in US Army soldiers and veterans. Nat. Mental Health 3, 1191–1201 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00505-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00505-4