Abstract

Study design:

Prospective cross-sectional survey.

Objectives:

To compare quality of life (QOL) for people with spinal cord injury (SCI) and their able-bodied peers and to investigate the relationship between QOL and disability (impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions) across the lifespan, for people with SCI.

Setting:

A community outreach service for people with SCI in Queensland, Australia.

Methods:

A random sample of 270 individuals who sustained SCI during the past 60 years was surveyed using a guided telephone interview format. The sample was drawn from the archival records of a statewide rehabilitation service. QOL was measured using the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Instrument-Bref, impairment was measured according to the American Spinal Injury Association classification and the Secondary Condition Surveillance Instrument, activity limitations using the motor subscale of the Functional Independence Measure and participation restrictions using the Community Integration Measure. Lifespan was considered in terms of age and time since injury. Correlation and regression analyses were employed to determine the relationship between QOL and components of disability across the lifespan.

Results:

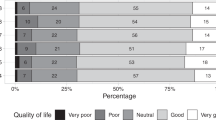

QOL was significantly poorer for people with SCI compared to the Australian norm. It was found to be associated with secondary impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions but not with neurological level, age or time since injury. The single most important predictor of QOL was secondary impairments whereas the second most important predictor was participation.

Conclusion:

To optimize QOL across the lifespan, rehabilitation services must maintain their focus on functional attainment and minimizing secondary conditions, although at the same time enabling participation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

O'Connor PJ . Prevalence of spinal cord injury in Australia. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 42–46.

Gething L, Fethney J, Jonas A, Moss N, Croft T, Ashenden C et al. Life after Injury: Quality of Life Issues for People with Traumatically-Acquired Brain Injury, Spinal Cord Injury and their Family Carers. Research Centre for Adaptation in Health and IIlness, University of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2002.

Westgren N, Levi R . Quality of life and traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 1433–1439.

Jain NB, Sullivan M, Kazis LE, Tun CG, Garshick E . Factors associated with health-related quality of life in chronic spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 86: 387–396.

Addington-Hall J, Walker L, Jones C, Karlsen S, McCarthy M . A randomised controlled trial of postal versus interviewer administration of a questionnaire measuring satisfaction with, and use of, services received in the year before death. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998; 52: 802–807.

The WHOQol Group. The development of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Instrument (the WHOQol). In: Orley J, Kuyken W (eds). Quality of Life Assessment: International Perspectives. Springer-Verlag: Heidleberg, 1994, pp 41–60.

Jang Y, Hsieh CL, Wang YH, Wu YH . A validity study of the WHOQOL-BREF assessment in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1890–1895.

Power M . Development of a common instrument for quality of life. In: Nosikov A, Gudex C (eds). EUROHIS: Developing Common Instruments for Health Surveys. IOS Press: Amsterdam, 2003, pp 145–163.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) 2006.

Weitzenkamp DA, Jones RH, Whiteneck GG, Young DA . Ageing with spinal cord injury: cross-sectional and longitudinal effects. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 301–309.

Seekins T, Clay J, Ravesloot C . A descriptive study of secondary conditions reported by a population of adults with physical disabilities served by three independent living centers in a rural state. J Rehabil 1994; 60: 47–51.

Masedo AI, Hanley M, Jensen MP, Ehde D, Cardenas DD . Reliability and validity of a self-report FIM (FIM-SR) in persons with amputation or spinal cord injury and chronic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 84: 167–176; quiz 177–9, 198.

McColl MA, Davies D, Carlson P, Johnston J, Minnes P . The community integration measure: development and preliminary validation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82: 429–434.

Cohen J . Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. 2nd ed. L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, 1988.

Murphy B, Herrman H, Hawthorne G, Pinzone T, Evert H . Australian WHO-QOL Instruments: User's Manual and Interpretation Guide. Australian WHOQOL Field Study Centre: Melbourne, Australia, 2000.

Hawthorne G, Herrman H, Murphy B . Interpreting the WHOQOL-Bref: preliminary population norms and effect sizes. Soc Indic Res 2006; 77: 37–59.

Kreuter M, Siosteen A, Erkholm B, Bystrom U, Brown DJ . Health and quality of life of persons with spinal cord lesion in Australia and Sweden. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 123–129.

Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE . Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med 1999; 48: 1507–1515.

Kemp B, Ettelson D . Quality of life while living and aging with a spinal cord injury and other impairments. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2001; 6: 116–127.

Norkeval TM, Wahl AK, Fridlund B, Nordrehaug JE, Wentzel-Larsen T, Hanestad BR . Quality of life in female myocardial infarction survivors: a comparative study with a randomly selected general female population cohort. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007; 5: 1477–7525.

Hammell KW . Quality of life after spinal cord injury: a metasynthesis of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 124–139.

Charlifue SW, Weitzenkamp DA, Whiteneck GG . Longitudinal outcomes in spinal cord injury: aging, secondary conditions, and well-being. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1429–1434.

Noreau L, Proulx P, Gagnon L, Drolet M, Laramee MT . Secondary impairments after spinal cord injury: a population-based study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 79: 526–535.

Pershouse K, Cox R, Dorsett P . Hospital readmissions in the first two years after initial rehabilitation for acute spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2000; 6: 23–33.

Dijkers M . Quality of life after spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis of the effects of disablement components. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 829–840.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarita Schuurs for data collection. Financial support for this project was provided by Queensland Health and the Centre of National Research on Disability and Rehabilitation (CONROD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barker, R., Kendall, M., Amsters, D. et al. The relationship between quality of life and disability across the lifespan for people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 47, 149–155 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.82

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.82

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Relationship between employment and quality of life and self-perceived health in people with spinal cord injury: an international comparative study based on the InSCI Community Survey

Spinal Cord (2024)

-

Current Quality of Life Metrics and Their Feasibility and Applicability in Adaptive Sports

Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports (2024)

-

An assessment of disability and quality of life in people with spinal cord injury upon discharge from a Bangladesh rehabilitation unit

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Quality of life after traumatic thoracolumbar spinal cord injury: a North Indian perspective

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

The role of mindfulness in quality of life of persons with spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional study

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes (2022)