Key Points

-

Patients' beliefs concerning scientific progress and the need to change standards of care can facilitate the acceptance of the NICE guideline.

-

Patients felt that the characteristics of the person advising them about the new guidance were an important determinant of whether or not they would accept them.

-

Patients preferred to have confirmation from their cardiologist before accepting the change.

Abstract

Background The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommendations in 2008 for antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatment contradict previous practice. There is a potential difficulty in explaining the new guidance to patients who have long believed that they must receive antibiotics before their dental treatment.

Aim This study investigated the patient-related barriers and facilitating factors in implementation of the NICE guidance.

Methods In-depth interviews were conducted with nine patients concerning their views about barriers and factors that could influence the implementation of the NICE guidance on antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatment. Data were analysed using framework analysis.

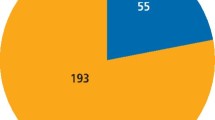

Results For patients the rationale for the NICE guidance was unclear. They understood that at the population level the risk of infective endocarditis was less than the risk of adverse reaction to antibiotics. However, on an individual level they felt that the latter risk was negligible given their previous experience of antibiotics. They were aware that standards of care change over time but were concerned that this may be an example where a mistake had been made. Patients felt that the characteristics of the person advising them about the new guidance were important in whether or not they would accept them – they wished to be advised by a clinician that they knew and trusted, and who was perceived as having appropriate expertise.

Conclusions Patients generally felt that they would be most reassured by information provided by a clinician who they felt they could trust and who was qualified to comment on the issue by respecting their autonomy. The implications of the findings for the development of patient information are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Ito H O . Infective endocarditis and dental procedures: evidence, pathogenesis, and prevention. J Med Invest 2006; 53: 189–198.

Prendergast B D . The changing face of infective endocarditis. Heart 2006; 92: 879–885.

Wilson W, Taubert K A, Gewitz M et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007; 116: 1736–1754.

Gould K F, Elliott T S J, Foweraker J et al. Guidelines for the prevention of endocarditis: report of the working party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 57: 1035–1042.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis in adults and children undergoing interventional procedures. Clinical guideline 64. London: NICE, 2008.

Department of Health. NICE guidance on 'Antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis'. Department of Health Chief Dental Officer Letter. London: Department of Health, 2008. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/Professionalletters/Chiefdentalofficerletters/DH_083679.

Harvey B . New guidance on antibiotic prophylaxis. Medical Defence Union website 2 April 2008. Available at: http://www.the-mdu.com.

Grimshaw J M, Shirran L, Thomas R et al. Changing provider behaviour: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care 2001; 39(8 Suppl 2): II2–II45.

Prior M, Guerin M, Grimmer-Somers K . The effectiveness of clinical guideline implementation strategies – a synthesis of systematic review findings. J Eval Clin Pract 2008; 14: 888–897.

NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Getting evidence into practice. Effective Health Care 1999; 5(1). http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/EHC/ehc51.pdf

Watt R, McGlone P, Evans D et al. The facilitating factors and barriers influencing change in dental practice in a sample of English general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 485–489.

Cabana M D, Rand C S, Powe N R et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999; 282: 1458–1465.

Oxman A D, Thomson M A, Davis D A, Haynes B . No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. Can Med Assoc J 1995; 153: 1423–1431.

Haines A, Donald A . Getting research findings into practice: making better use of research findings. BMJ 1998; 317: 72–75.

Grol R, Grimshaw J M . From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet 2003; 362: 1225–1230.

Ní Ríordáin R, McCreary C . NICE guideline on antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: attitudes to the guideline and implications for dental practice in Ireland. Br Dent J 2009; 206: E11.

Newton T, Scambler S . Use of qualitative data in oral health research. Community Dent Health 2010; 27: 66–67.

Ritchie J, Spencer L . Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Bryman A, Burgess R (eds) Analysing qualitative data. pp 173–194. London: Routledge, 1994.

Pope C, Zeibland S, Mays N . Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000; 320: 114–116.

Boon N . British Cardiovascular Society antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis position statement. London: British Cardiovascular Society, 2008.

Krahn M, Naglie G . The next step in guideline development: incorporating patient preferences. JAMA 2008; 300: 436–438.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Tehran, Iran as part of the PhD project of the first author (SS) in King's College London. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of all those patients who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Soheilipour, S., Scambler, S., Dickinson, C. et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in dentistry: part II. A qualitative study of patient perspectives and understanding of the NICE guideline. Br Dent J 211, E2 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.525

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.525

This article is cited by

-

Communicating new policy on antibiotic prophylaxis with patients: a randomised controlled trial

British Dental Journal (2013)

-

NICE guideline and current practice of antibiotic prophylaxis for high risk cardiac patients (HRCP) among dental trainers and trainees in the United Kingdom (UK)

British Dental Journal (2012)

-

An Update on Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Dermatologic Surgery

Current Dermatology Reports (2012)

-

Whatever you think is best, doctor

British Dental Journal (2011)

-

Summary of: Antibiotic prophylaxis in dentistry: part II. A qualitative study of patient perspectives and understanding of the NICE guideline

British Dental Journal (2011)