Abstract

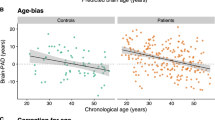

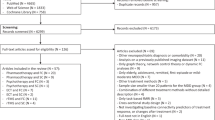

The objective of our study was to elucidate distinct paths to depression in a model that incorporates age, measures of medical comorbidity, neuroanatomical compromise, and cognitive status in a sample of patients with late-life major depressive disorder (MDD) and nondepressed controls. Our study was cross-sectional in nature and utilized magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) estimates of brain and high-intensity lesion volumes together with clinical indices of cerebrovascular and nonvascular medical comorbidity. Neuroanatomic and clinical measures were incorporated into a structural covariance model in order to test pathways to MDD. Our data indicate that there are two paths to MDD; one path is represented by vascular and nonvascular medical comorbidity that contribute to high-intensity lesions that lead to depression. Smaller brain volumes represent a distinct path to the mood disorder. Age influences depression by increasing atrophy and overall medical comorbidity but has no direct impact on MDD. These findings demonstrate that there are distinct biological substrates to the neuroanatomical changes captured on MRI. These observations further suggest that neurobiological mechanisms acting in parallel may compromise brain structure/function, thereby predisposing individuals to clinical brain disorders such as depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Mattis S, Kakuma T . (1993): The course of geriatric depression with “reversible dementia”: A controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 150: 1693–1699

Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kakuma T, Silbersweig D, Charlson M . (1997): Clinically defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry 154: 562–565

Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kalayam B, Kakuma T, Gabrielle M, Sirey JA, Hull J . (2000): Executive dysfunction and long-term outcomes of geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 285–290

American Heart Association. (1990): Stroke Risk Factor Prediction Chart. Dallas, American Heart Association

American Psychiatric Association. (1994): Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press

Awad IA, Spetzler RF, Hodak JA, Awad CA, Carey R . (1986): Incidental subcortical lesions identified on magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly. I. Correlation with age and cerebrovascular risk factors. Stroke 17: 1084–1089

Blazer D, Hughes DC, George LK . (1987): The epidemiology of depression in an elderly community population. Gerontologist 27: 281–287

Bollen KA . (1989): Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York, John Wiley & Sons

Borson S, Claypoole K, McDonald G . (1998): Depression and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Treatment trials. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry 3: 115–130

Braffman BH, Zimmerman RA, Trojanowski JQ, Gonatas NK, Hickey WF, Schlaepfer WW . (1988): Brain MR: Pathologic correlation with gross and histopathology. 1. Lacunar infarction and Virchow-Robin spaces. 2. Hyperintense white-matter foci in the elderly. Am J Roentgenol 151: 551–558

Caine ED, Lyness JM, King DA . (1993): Reconsidering depression in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1: 4–20

Coffey CE, Wilkinson WE, Weiner RD, Parashos IA, Djang WT, Webb MC, Figiel GS, Spritzer CE . (1993): Quantitative cerebral anatomy in depression. A controlled magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50: 7–16

Coulehan JL, Schulberg HC, Block MR, Janosky JE, Arena VC . (1990): Medical comorbidity of major depressive disorder in a primary medical practice. Arch Intern Med 150: 2363–2367

Cowell PE, Turetsky BI, Gur RC, Grossman RI, Shtasel DL, Gur RE . (1994): Sex differences in aging of the human frontal and temporal lobes. J Neurosci 14: 4748–4755

Drayer BP . (1988): Imaging of the aging brain. Part I. Normal findings. Part II. Pathologic conditions. Radiology 166: 785–796

Duman RS, Charney DS . (1999): Cell atrophy and loss in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 45: 1083–1084

Emery VO, Oxman TE . (1992): Update on the dementia spectrum of depression. Am J Psychiatry 149: 305–317

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR . (1975): “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198

Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M . (1995): Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction [published erratum appears in Circulation 1998 Feb 24:708]. Circulation 91: 999–1005

Gierz M, Jeste DV . (1993): Physical comorbitidy in elderly schizophrenic and depressed patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1: 165–170

Gould E, Tanapat P, McEwen BS, Flugge G, Fuchs E . (1998): Proliferation of granule cell precursors in the dentate gyrus of adult monkeys is diminished by stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 3168–3171

Hamilton M . (1967): Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 6: 278–296

Henderson AS, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Mackinnon AJ, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Rodgers B . (1997): The course of depression in the elderly: A longitudinal community-based study in Australia. Psychol Med 27: 119–129

Hickie I, Scott E . (1998): Late-onset depressive disorders: A preventable variant of cerebrovascular disease? Psychol Med 28: 1007–1013

Katz IR . (1996): On the inseparability of mental and physical health in aged persons: Lessons from depression and medical comorbidity. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 4: 1–16

Katz IR, Striem J, Parmelee P . (1994): Psychiatric-medical comorbidity: Implications for health services delivery and for research on depression. Biol Psychiatry 36: 141–145

Kraemer HC, Yesavage JA, Taylor JL, Kupfer D . (2000): How can we learn about developmental processes from cross-sectional studies, or can we? Am J Psychiatry 157: 163–171

Krishnan KR . (1993): Neuroanatomic substrates of depression in the elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 6: 39–58

Krishnan KR, Hays JC, Blazer DG . (1997): MRI-defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry 154: 497–501

Kumar A, Miller D, Ewbank D, Yousem D, Newberg A, Samuels S, Cowell P, Gottlieb G . (1997a): Quantitative anatomic measures and comorbid medical illness in late-life major depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 5: 15–25

Kumar A, Schweizer E, Jin Z, Miller D, Bilker W, Swan LL, Gottlieb G . (1997b): Neuroanatomical substrates of late-life minor depression. A quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Neurol 54: 613–617

Kumar A, Jin Z, Bilker W, Udupa J, Gottlieb G . (1998): Late-onset minor and major depression: Early evidence for common neuroanatomical substrates detected by using MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7654–7658

Kumar A, Bilker W, Jin A . (2000): Atrophy and high intensity lesions: Complementary neurobiological mechanisms in late-life major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 22: 264–274

Lacro JP, Jeste DV . (1994): Physical comorbidity and polypharmacy in older psychiatric patients. Biol Psychiatry 36: 146–152

Lai TJ, Payne ME, Byrum CE, Steffens DC, Krishnan KR . (2000): Reduction of orbital frontal cortex volume in geriatric depression. Biol Psychiatry 48: 971–975

Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L . (1968): Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 16: 622–626

Lopez JF, Chalmers DT, Little KY, Watson SJ . (1998): A.E. Bennett Research Award. Regulation of serotonin1A, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid receptor in rat and human hippocampus: Implications for the neurobiology of depression. Biol Psychiatry 43: 547–573

Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Gavard JA, Clouse RE . (1992): Depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 15: 1631–1639

Lyness JM, Caine ED, Cox C, King DA, Conwell Y, Olivares T . (1998): Cerebrovascular risk factors and later-life major depression. Testing a small-vessel brain disease model. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 6: 5–13

Mintz J, Dixon W . (1997): Objection overruled: A comment on Gastwirth, Krieger, and Rosenbaum. American Statistician 51: 117–119

Morris P, Rapoport SI . (1990): Neuroimaging and affective disorder in late life: A review. Can J Psychiatry 35: 347–354

Muthen B . (1984): A general structural equation model with dichotomous, ordered categorical, and continuous latent variable indicators. Psychometrika 49: 115–132

National Institutes of Health. (1992): NIH consensus conference. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. JAMA 268: 1018–1024

O'Brien J, Desmond P, Ames D, Schweitzer I, Harrigan S, Tress B . (1996): A magnetic resonance imaging study of white matter lesions in depression and Alzheimer's disease [published erratum appears in Br J Psychiatry 1996 168:792]. Br J Psychiatry 168: 477–485

Parmalee PA, Katz IR, Lawton MP . (1992): Incidence of depression in long term care settings. J Gerontol 47: M189–M196

Penninx BW, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJ, van Eijk JT, van Tilburg W, Beekman AT . (1999): Minor and major depression and the risk of death in older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56: 889–895

Rabins PV, Pearlson GD, Aylward E, Kumar AJ, Dowell K . (1991): Cortical magnetic resonance imaging changes in elderly inpatients with major depression. Am J Psychiatry 148: 617–620

Rajkowska G . (2000): Postmortem studies in mood disorders indicate altered numbers of neurons and glial cells. Biol Psychiatry 48: 766–777

Rajkowska G, Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Wei J, Dilley G, Pittman SD, Meltzer HY, Overholser JC, Roth BL, Stockmeier CA . (1999): Morphometric evidence for neuronal and glial prefrontal cell pathology in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 45: 1085–1098

Sapolsky RM, Pulsinelli WA . (1985): Glucocorticoids potentiate ischemic injury to neurons: Therapeutic implications. Science 229: 1397–1400

Sato R, Bryan RN, Fried LP . (1999): Neuroanatomic and functional correlates of depressed mood: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 150: 919–929

Sheline YI . (2000): 3D MRI studies of neuroanatomic changes in unipolar major depression: The role of stress and medical comorbidity. Biol Psychiatry 48: 791–800

Sheline YI, Wang PW, Gado MH, Csernansky JG, Vannier MW . (1996): Hippocampal atrophy in recurrent major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 3908–3913

Spangler KM, Challa VR, Moody DM, Bell MA . (1994): Arteriolar tortuosity of the white matter in aging and hypertension. A microradiographic study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 53: 22–26

Steffens DC, Helms MJ, Krishnan KR, Burke GL . (1999): Cerebrovascular disease and depression symptoms in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke 30: 2159–2166

Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, Wells K, Rogers WH, Berry SD, McGlynn EA, Ware JE Jr . (1989): Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 262: 907–913

Udupa J, Samarasekera S . (1996): Fuzzy connectedness and object definition: theory, algorithms, and applications in image segmentation. Graphical Models and Image Processing 58: 246–261

Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, Grembowski D, Walker E, Rutter C, Katon W . (1997): Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. A 4-year prospective study. JAMA 277: 1618–1623

Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD . (1989): The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 277: 1618–1623

Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB . (1991): Probability of stroke: A risk profile from the Framingham Study. Stroke 22: 312–318

Ylikoski A, Erkinjuntti T, Raininko R, Sarna S, Sulkava R, Tilvis R . (1995): White matter hyperintensities on MRI in the neurologically nondiseased elderly. Analysis of cohorts of consecutive subjects aged 55 to 85 years living at home. Stroke 26: 1171–1177

Zubenko GS, Marino LJ Jr, Sweet RA, Rifai AH, Mulsant BH, Pasternak RE . (1997): Medical comorbidity in elderly psychiatric inpatients. Biol Psychiatry 41: 724–736

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIMH grants MH 55115 and MH61567 (AK) and NIMH grant MH 52129 (Clinical Research Center for Depression in Late Life). Presented in Part at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, New Orleans, Oct 2000

STATISTICAL ENDNOTE

The statistical methodology of path analysis remains relatively unfamiliar in the neurosciences. It is an extension of regression analysis that attempts to separate causal influences among a set of variables into direct and indirect (or mediating) pathways. Path analysis makes it possible to model more complex systems than is possible with usual multiple regression models that include only a single dependent variable. Path models typically include intervening variables, often at multiple causal levels, and may omit paths presumed to be irrelevant. Using the methods of structural equation modeling (SEM), overall evaluation of an entire postulated system of causal relations is possible.

Multiple logistic regression analysis, as employed in a previous report of this study (Kumar et al. 2000), evaluates the significance of direct associations from a set of predictor variables to the occurrence of depression. Path analysis, as employed in this report, makes it possible to simultaneously evaluate the statistical plausibility of the entire set of posited causal relationships. As depicted in the main Figure 1, this is a multilevel model that includes both direct and indirect causal paths. The goodness-of-fit χ2 tests the deviation of the data from the model. When significant, it indicates that the data do not fit the posited causal model. Thus, a nonsignificant goodness-of-fit χ2 is desirable, in that it indicates that the posited causal model is statistically plausible in light of the observed data. Of course, the fact that a model is plausible does not guarantee that it is correct. It is not at all uncommon for several alternative models to “fit” the data (as occurred in this case).

The Mplus software makes it possible to simultaneously evaluate multistage models including both continuous and dichotomous dependent variables. In the former case, the path (regression) coefficients are conventional linear regression coefficients, indicating the expected change in the dependent variable for a unit change in the independent variable. In the case of dichotomous dependent variables (e.g., depression in the current analyses), the coefficients are probit coefficients. As such, they represent the change in the probability of “caseness” associated with a unit change in the independent variable. The model underlying the probit portion of the analysis is that the likelihood of observing the outcome (depression in this case) is based on one's position on a hypothetical, unobserved normal curve. The probit equation estimates a linear combination of predictors to predict the z-score representing one's position on that curve and thus the probability of being a case.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, A., Mintz, J., Bilker, W. et al. Autonomous Neurobiological Pathways to Late-Life Major Depressive Disorder: Clinical and Pathophysiological Implications. Neuropsychopharmacol 26, 229–236 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00331-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00331-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Quantitative Tract-Specific Measures of Uncinate and Cingulum in Major Depression Using Diffusion Tensor Imaging

Neuropsychopharmacology (2012)

-

Temporal Lobe Atrophy and White Matter Lesions are Related to Major Depression over 5 years in the Elderly

Neuropsychopharmacology (2010)

-

Translational Research in Late-Life Mood Disorders: Implications for Future Intervention and Prevention Research

Neuropsychopharmacology (2007)

-

Volumetric brain imaging studies in the elderly with mood disorders

Current Psychiatry Reports (2006)

-

Vascular depression: Recent advances

Current Psychosis and Therapeutics Reports (2004)