Abstract

Primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma has a poor prognosis relative to other extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Recently, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma has been subclassified as germinal center B-cell-like and nongerminal center B-cell types using tissue microarrays. The 5-year overall survival rate of the germinal center B-cell group is better than that of the nongerminal center B-cell group. To elucidate the reason for which primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma has a poor clinical outcome, we investigated 15 patients with primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (stage IE; 13 cases, stage IIE; two cases) by immunohistochemistry using various markers including CD10, Bcl-6, MUM1 and MIB-1 and by molecular analysis of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene variable region. Immunohistochemistry showed 0/15 (positive cases/examined cases) for CD10, 5/15 for Bcl-6, 15/15 for MUM1, 10/15 for Bcl-2, 2/15 for CD5 and 4/15 for CD40. The expression pattern of CD10(−) MUM1(+) in primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma corresponded to the nongerminal center B-cell group. Moreover, the MIB-1 index was distributed from 60 to 95% with a mean of 79%, indicating a high proliferation of the lymphoma cells. The immunoglobulin heavy chain gene variable region of primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma had a mutation frequency of 1–10% (seven cases) and 0–1 additional mutations in ongoing mutation analysis (five cases). Primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma had characteristics of the nongerminal center B-cell group. In conclusion, primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma has a nongerminal center B-cell phenotype and has a high MIB-1 index. These features might therefore be associated with poor prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Primary breast lymphoma is a very uncommon condition that accounts for 0.05–0.53% of all malignant diseases of the breast and 2.2% of extranodal malignant lymphomas.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Clinicopathologic characteristics of primary breast lymphoma have been well investigated to date. Almost all primary breast lymphoma has a B-cell phenotype, while primary breast lymphoma with T-cell phenotype is extremely rare. In all, 46–71% of primary breast lymphoma are diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL).2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13 The age distribution of primary breast lymphoma patients is bimodal; younger patients with a peak of 30–35 years frequently constitute DLBCL and a small number of Burkitt lymphomas with bilateral tumors, whereas older patients with a peak of 55–60 years constitute DLBCL and/or marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT-type lymphoma) with unilateral tumors.8, 9, 11 Primary breast lymphoma is reported to exhibit a poor prognosis among extranodal B-cell lymphomas. The overall survival rate of primary breast lymphoma with a B-cell phenotype is 43% at 5 years. This is worse than those reported in the thyroid: 79% 5-year disease-specific survival14 and Waldeyer's ring: 70% 5-year overall survival,15 but is better than central nervous system (CNS) lymphomas: 37% 2 year overall survival.16 Moreover, the 5-year overall survival of the gastrointestinal high-grade B-cell lymphoma is 63%,17 on the other hand, the median survival of primary breast DLBCL is reported to be 36 months.18 The reasons for which primary breast lymphoma, especially DLBCL is worse compared to other extranodal malignant lymphoma is unknown.

It has been recently shown that DLBCL can be divided into three prognostically important subgroups: germinal center B-cell-like DLBCL, activated B-cell-like DLBCL , and type 3 by gene expression profiles using a cDNA microarray.19, 20 Germinal center B-cell-like DLBCL has a better clinical outcome than activated B-cell and type 3. Hans et al21 subsequently reported that the immunohistochemical expression pattern of CD10, Bcl-6 and MUM1 can be used to categorize DLBCL into and nongerminal center B-cell type, including activated B-cell and type 3, with an outcome similar to that predicted by cDNA microarray analysis.

In this article, we therefore investigate 15 patients with primary breast DLBCL in stages I and II, with immunohistochemistry using various markers including germinal center B-cell markers, nongerminal center B-cell type markers and MIB-1, and molecular analysis of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene variable region (IgH-V gene) to elucidate the biological characteristics of primary breast lymphoma.

Patients and methods

Patients

In all, 15 patients with primary breast lymphoma at stage IE (13 cases) or at stage IIE (two cases) were retrieved from the lymphoma files of Department of Pathology at Fukushima Medical University. Because breast lymphoma with generalized disease in the III and IV clinical stages is considered to be primary or secondary lymphoma, these patients were excluded from this study. Patients with bilateral lesions were also excluded in order to carry out immunohistochemical and biological analysis for primary lesions.

All patients underwent surgery for either tumor excision (four cases) or mastectomy (11 cases). All patients fulfilled the criteria for primary breast lymphoma proposed by Wiseman and Liao:10 adequate pathological specimen, close association of breast tissue and lymphomatous infiltrate, and no other lymphomatous focus at the time of diagnosis except for the presence of ipsilateral axillary nodes provided that nodal involvement occurred concomitantly with the primary breast lesion. Patients were assigned to either IE or IIE stages at the time of diagnosis, according to the Ann Arbor staging system applied to primary extranodal lymphomas.22

Routine Light Microscopy

Resected tissue was fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. A portion of the sample of four cases was frozen. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and primary breast DLBCL was diagnosed according to the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissue.23

Immunohistochemistry

Immunoperoxidase staining was performed using an avidin–biotin-peroxidase complex technique on both paraffin-embedded sections and frozen sections.24 Deparaffinized and dehydrated tissue sections were pretreated by microwaves and stained with murine antibodies (Table 1). The MIB-1 index was evaluated for proliferative activity of lymphoma cells. Well-stained areas in MIB-1 and CD20 double stainings were selected. Doubly positive large cells (MIB-1 plus CD20) and CD20-positive large cells were counted under high-power fields (× 400). At least 350 CD20-positive cells were counted. The mean percentage under three high-power fields was considered to be the MIB-1 index.

Molecular Investigation

DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded or frozen tissues using a DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen Co., Valencia, CA, USA). The variable (CDR1, FW2, CDR2 and FW3) and the VDJ regions (CDR3) of the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene were amplified by seminested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as previously described.25, 26 The primers used in this study were as follows: 5′-AGGTGCAGCTG[C/G][A/G/T]G[C/G]AGTC[A/G/T]GG-3′(FR1C) and 5′-TGG[A/G] TCCG[C/A] CAG [G/C] C [T/C][T/C] C [A/C/G/T] GG-3′(FR2A), as an upstream consensus V region primer; 5′-TGAGGAGACGGTGACC-3′, as a consensus J region primer (LJH); and 5′-GTGACCAGGGT[A/C/G/T]CCTTGGCCCC AG-3′, as a consensus J region primer (VLJH).25 The nucleotide sequences between CDR1 and FW3 or CDR2 and FW3 were analyzed using HITACHI SQ-5500 (Tokyo, Japan) and compared with the germline sequences recorded in the gene bank database. Somatic mutations of the IgH gene variable region (IgH-V gene) were analyzed using the Ig blast site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/igblast/).

The presence or absence of ongoing mutations was determined according to a previously described method.27 Briefly, PCR products were ligated into the PCRR 2.1 vector and transformed into TOP10F′ cells according to the manufacturer's instructions (original TA cloning kit; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A colony direct PCR assay was used to determine whether colonies included the correct PCR product. A total of 10 or more white colonies were selected and placed into 50 μl of Insert Check ready (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). PCR amplification consisted of 30 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 60°C for 5 s and 72°C for 30 s. Then, 10 samples including correct PCR products confirmed by check-electrophoresis for each case were sequenced by the same method.

Results

Clinical Features

The clinical features and outcomes of patients are summarized in Table 2. Age at diagnosis ranged from 45 to 81 years (median, 68). Four patients with tumors under 5 cm did not relapse. Six (all belonged to stage IE) of 11 patients with tumors larger than 5 cm were relapsed. Of the six patients who relapsed, four died of lymphoma. Both patients with stage IIE survived and did not relapse. There was no relationship among tumor size, LDH ratio, IPI and staging.

Histological and Immunohistochemical Findings

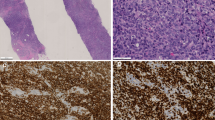

Histological and immunohistochemical findings in paraffin sections are shown in Table 3. The lymphoma constituted a poorly circumscribed mass, infiltrated the breast lobules and surrounded breast ducts. All patients showed a diffuse infiltration of closely packed large-sized lymphoma cells, and a diagnosis of DLBCL was made (Figure 1). A lymphoepithelial lesion was seen in six cases. Two (cases 1 and 2) were DLBCL with MALT-type lymphoma (Figure 2) and four (cases 3–6) were DLBCL without MALT-type lymphoma.

DLBCL with MALT-type lymphoma (case 1). (a) Hematoxylin–Eosin (HE) stain shows large-size lymphoma cells on the left side and small- to medium-size cells on the right side. Lymphoepithelial lesion is found in the upper right-hand corner. (b) HE stain shows lymphoepithelial lesion by small cell. (c) AE1/3 immunostain shows destroyed epithelium (lymphoepithelial lesion).

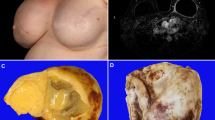

Immunohistochemistry showed CD3;0/15 (positive cases/examined cases), CD5; 2/15, CD10; 0/15, CD20; 15/15, CD21; 0/15, CD23; 0/15 CD27; 0/15, CD30; 1/15, CD40; 4/15; CD56; 0/15, CD138; 0/15, Bcl-2; 10/15, Bcl-6; 5/15, IRF4/MUM1; 15/15, granzyme B; 0/15, LMP-1; 0/15, cyclin D1; 0/15, p21; 0/15, p27; 7/15, p53; 0/15, TdT; 0/15 and TIA-1; 0/15 (Figure 3). The MIB-1 index ranged from 59 to 95% and the mean MIB-1 index was 79% (Figure 4).

A MIB-1/CD20-double immunostaining of the paraffin-embedded section (case 8). MIB-1 stains the nuclei, while CD20 stains the cytoplasm and cell membrane. MIB-1/CD20 doubly labelled cells were counted. The mean percentages under three high-power fields was evaluated as the MIB-1 index. Totally, 95.2% of MIB-1 index is found in this slide.

Molecular Findings

The IgH-V gene was analyzed in seven patients. The results of somatic mutations and ongoing mutations of the IgH-V gene are shown in Table 4. The frequency of mutations ranged from 1 to 10%. The usage of the VH family was VH4 in four cases and VH3 in three cases. Overall, 10 clones were examined for ongoing mutations in five patients. Three cases showed no additional mutations and the other two showed only one additional mutation.

Discussion

We investigated immunohistochemical and molecular features in 15 patients with primary breast DLBCL to elucidate the biological characteristics of primary breast lymphoma and why primary breast lymphoma has a poor prognosis. For these aims, we selected patients with breast DLBCL in stages IE/IIE, such that this study included patients older than 45 years of age.

All cases immunohistochemically showed CD10(−) and MUM1(+). Bcl-6 was expressed in five of 15 cases. According to the system of Hans et al,21 DLBCL cases of CD10(+) or CD10(−) Bcl-6 (+) MUM1(−) were subclassified as germinal center B-cell type, whereas DLBCL cases with the other expression patterns were subclassified as non-germinal center B-cell type. Regardless of Bcl-6 expression, CD10(−) cases with MUM1(+) were subclassified as nongerminal center B-cell type. Thus, primary breast DLBCL in our cases was subclassified as the nongerminal center B-cell group. Hans et al reported that the tissue microarrays for immunohistochemistry divided 152 DLBCL into germinal center B-cell type (64 patients; 42%) and nongerminal center B-cell type (88 patients; 58%) and that the overall survival rates at 5 years for germinal center B-cell type and nongerminal center B-cell type cases were 76 and 34%, respectively. Nongerminal center B-cell type is one of the major predictors of poor DLBCL prognosis. They also mentioned that this classification recapitulated the gene expression results by cDNA microarrays in 71% of germinal center B-cell-like DLBCL and 88% of nongerminal center B-cell-like DLBCL cases, and that it mirrored the predicted for survival in a similar manner. Primary breast DLBCL is a major predictor of poor prognosis.

Hans et al21 also reported that 43% patients in nongerminal center B-cell type expressed Bcl-2 and Bcl-2(+) cases showed significantly worse prognosis than Bcl-2 (−) patients in nongerminal center B-cell type (50 patients; 57%). Two-thirds of the cases in our study were positive for Bcl-2, which is an additional factor for poor prognosis. In addition, the Nordic group reported that 76% of DLBCL expressed CD40 and CD40(+) DLBCL showed better prognosis than CD40(−) DLBCL.28 In our series, CD40 was positive in only 27% of cases. CD5 expression is known to be a disadvantage for chemotherapy28, 29 and two cases expressed CD5. Immunohistochemical phenotypes of primary breast DLBCL, therefore, can predict their poor prognosis.

Second, we found a very high MIB-1 index of primary breast DLBCL, ranging from 60 to 95%. MIB-1 index has a relationship to prognosis in B-cell lymphomas.30, 31, 32 The MIB-1 index in the other extranodal sites, those of DLBCL with MALT-type lymphoma in the stomach and of DLBCL in the CNS were reported to be 51 and 50%, respectively.33, 34 These clearly indicate an exceptionally high proliferative activity in primary breast DLBCL that may account for the high recurrence rate in stage IE disease.

Although the IgH-V gene showed somatic hypermutations in seven cases ranging from 1 to 10% indicating that the primary breast DLBCL was derived from the germinal center B-cell or the post germinal center B-cell,27, 35, 36 ongoing mutations were absent in all examined five cases. Germinal center B-cell type DLBCL by cDNA microarray demonstrated the presence of ongoing mutations, but in activated B-cell types DLBCL showed no evidence of ongoing mutations.37 This also indicated primary breast DLBCL did not belong to the germinal center B-cell type DLBCL.

The frequency of mutations ranged from 1 to 10% for primary breast DLBCL and was similar to those of primary gastrointestinal DLBCL ranging 1.39–15.65%.38 While the mutation frequency in DLBCL with MALT-type lymphomas (case 1) or with lymphoepithelial lesion (cases 3, 4 and 6) were over 4%, which of DLBCL without MALT-type lymphomas or lymphoepithelial lesion (cases 9 and 13) was less than 3%. This suggests that DLBCL transformed from MALT-type lymphoma and de novo DLBCL might demonstrate different values in somatic mutation frequency.

The usage of the VH family of primary breast DLBCL was different from other extranodal lymphomas. In the current study, the usage of VH family was VH4 in four and all of them were VH4-34. The remaining three cases used VH3 family. Lossos et al39 reported that 53 cases of nodal and extranodal DLBCL used VH3 most often, followed by VH4, VH1 VH2 H5 and VH7. VH4-34 was used in only five cases. In gastric DLBCL, five of six cases used VH3 family.38 The high frequency of VH4-34 in primary breast DLBCL might be a feature of this disease.

Recent studies, especially in gastric lymphoma, suggests that de novo DLBCL and DLBCL transformed from MALT-type lymphoma is another category in pathogenesis and prognosis,40, 41 but the significant difference in primary breast DLBCL is not clear yet. In our study, DLBCL with or without MALT-type lymphoma showed same nongerminal center B-cell phenotype. Current study, analyzed DLBCL with MALT-type lymphoma is only two cases. More large size studies about germinal center B-cell and nongerminal center B-cell phenotype in primary breast and other extranodal DLBCL with and without MALT type are expected.

In conclusion, primary breast DLBCL with and without MALT-type lymphoma shows nongerminal center B-cell type and high proliferative activity. These dates might be associated with a worse prognosis in primary breast DLBCL.

References

Arber DA, Simpson JF, Weiss LM, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma involving the breast. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:288–295.

Cohen Y, Goldenberg N, Kasis S, et al. Primary breast lymphoma. Harefuah 1993;125:24–26 63.

Mattia AR, Ferry JA, Harris NL . Breast lymphoma. A B-cell spectrum including the low grade B-cell lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:574–587.

Sokolov T, Shimonov M, Blickstein D, et al. Primary lymphoma of the breast: unusual presentation of breast cancer. Eur J Surg 2000;166:390–393.

Brogi E, Harris NL . Lymphomas of the breast: pathology and clinical behavior. Semin Oncol 1999;26:357–364.

Aozasa K, Ohsawa M, Saeki K, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the breast. Immunologic type and association with lymphocytic mastopathy. Am J Clin Pathol 1992;97:699–704.

Hugh JC, Jackson FI, Hanson J, et al. Primary breast lymphoma. An immunohistologic study of 20 new cases. Cancer 1990;66:2602–2611.

Jeon HJ, Akagi T, Hoshida Y, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin malignant lymphoma of the breast. An immunohistochemical study of seven patients and literature review of 152 patients with breast lymphoma in Japan. Cancer 1992;70:2451–2459.

Giardini R, Piccolo C, Rilke F . Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphomas of the female breast. Cancer 1992;69:725–735.

Wiseman C, Liao KT . Primary lymphoma of the breast. Cancer 1972;29:1705–1712.

Nakamura N, Ono N, Tominaga K, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the breast: a report on five cases and a review of the literature. Saishin Igaku 1988;43:2281–2290.

Ha CS, Dubey P, Goyal LK, et al. Localized primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the breast. Am J Clin Oncol 1998;21:376–380.

Smith MR, Brustein S, Straus DJ . Localized non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the breast. Cancer 1987;59:351–354.

Derringer GA, Thompson LD, Frommelt RA, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the thyroid gland: a clinicopathologic study of 108 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:623–639.

Yong W, Zhang Y, Zheng W, et al. Prognostic factors and therapeutic efficacy of combined radio-chemotherapy in Waldeyer's ring non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2000;113:148–150.

Ferreri AJ, Blay JY, Reni M, et al. Prognostic scoring system for primary CNS lymphomas: the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group experience. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:266–272.

Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Iida M, et al. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma in Japan: a clinicopathologic analysis of 455 patients with special reference to its time trends. Cancer 2003;97:2462–2473.

Abbondanzo SL, Seidman JD, Lefkowitz M, et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the breast. A clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Pathol Res Pract 1996;192:37–43.

Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature 2000;403:503–511.

Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1937–1947.

Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004;103:275–282.

Rosenberg SA . Validity of the Ann Arbor staging classification for the non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Cancer Treat Rep 1977;61:1023–1027.

Jaffe E, Harris N, Stein H, et al. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors: Pathology and Genetics: Tumors of Heamatopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC Press: Lyon, 2001.

Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H . The use of antiavidin antibody and avidin–biotin-peroxidase complex in immunoperoxidase technics. Am J Clin Pathol 1981;75:816–821.

Hummel M, Tamaru J, Kalvelage B, et al. Mantle cell (previously centrocytic) lymphomas express VH genes with no or very little somatic mutations like the physiologic cells of the follicle mantle. Blood 1994;84:403–407.

Kuze T, Nakamura N, Hashimoto Y, et al. Most of CD30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma of B cell type show a somatic mutation in the IgH V region genes. Leukemia 1998;12:753–757.

Nakamura N, Hashimoto Y, Kuze T, et al. Analysis of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene variable region of CD5-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Lab Invest 1999;79:925–933.

Linderoth J, Jerkeman M, Cavallin-Stahl E, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of CD23 and CD40 may identify prognostically favorable subgroups of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a Nordic Lymphoma Group Study. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9:722–728.

Yamaguchi M, Seto M, Okamoto M, et al. De novo CD5+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 109 patients. Blood 2002;99:815–821.

Miller TP, Grogan TM, Dahlberg S, et al. Prognostic significance of the Ki-67-associated proliferative antigen in aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: a prospective Southwest Oncology Group trial. Blood 1994;83:1460–1466.

Llanos M, Alvarez-Arguelles H, Aleman R, et al. Prognostic significance of Ki-67 nuclear proliferative antigen, bcl-2 protein, and p53 expression in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Med Oncol 2001;18:15–22.

Tominaga K, Yamaguchi Y, Nozawa Y, et al. Proliferation in non-Hodgkin's lymphomas as determined by immunohistochemical double staining for Ki-67. Hematol Oncol 1992;10:163–169.

Nakamura S, Akazawa K, Yao T, et al. A clinicopathologic study of 233 cases with special reference to evaluation with the MIB-1 index. Cancer 1995;76:1313–1324.

Krogh-Jensen M, Johansen P, D'Amore F . Primary central nervous system lymphomas in immunocompetent individuals: histology, Epstein–Barr virus genome, Ki-67 proliferation index, p53 and bcl-2 gene expression. Leuk Lymphoma 1998;30:131–142.

Cleary ML, Meeker TC, Levy S, et al. Clustering of extensive somatic mutations in the variable region of an immunoglobulin heavy chain gene from a human B cell lymphoma. Cell 1986;44:97–106.

Nakamura N, Kuze T, Hashimoto Y, et al. Analysis of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene variable region of 101 cases with peripheral B cell neoplasms and B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the Japanese population. Pathol Int 1999;49:595–600.

Lossos IS, Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, et al. Ongoing immunoglobulin somatic mutation in germinal center B cell-like but not in activated B cell-like diffuse large cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:10209–10213.

Go JH, Kim DS, Kim TJ, et al. Comparative studies of somatic and ongoing mutations in immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region genes in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of the stomach and the small intestine. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2003;127:1443–1450.

Lossos IS, Okada CY, Tibshirani R, et al. Molecular analysis of immunoglobulin genes in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood 2000;95:1797–1803.

Hsi ED, Eisbruch A, Greenson JK, et al. Classification of primary gastric lymphomas according to histologic features. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:17–27.

Starostik P, Patzner J, Greiner A, et al. Gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of MALT type develop along 2 distinct pathogenetic pathways. Blood 2002;99:3–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshida, S., Nakamura, N., Sasaki, Y. et al. Primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma shows a non-germinal center B-cell phenotype. Mod Pathol 18, 398–405 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800266

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800266

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Clinicopathological features of thirty patients with primary breast lymphoma and review of the literature

Medical Oncology (2015)

-

Primary breast lymphoma (PBL): A literature review

Clinical Oncology and Cancer Research (2011)

-

Most primary central nervous system diffuse large B-cell lymphomas occurring in immunocompetent individuals belong to the nongerminal center subtype: a retrospective analysis of 31 cases

Modern Pathology (2010)

-

Primary Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Oral Cavity: Germinal Center Classification

Head and Neck Pathology (2010)

-

Primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma of the breast eight years after the diagnosis of gastric MALT lymphoma: report of first case

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2010)