Abstract

Urethral and penile tissues and their neoplasms are considered anatomically and pathogenetically different. Since we observed urethral dysplastic lesions and some similarities between noninvasive and invasive lesions of the anterior urethra and glans, we designed this study to document epithelial urethral abnormalities in patients with penile squamous cell carcinoma. We examined urethral epithelia from 170 penectomies with invasive squamous cell carcinoma finding a variety of primary epithelial abnormalities in 89 cases (52%) and secondary invasion of penile carcinoma to urethra in 42 cases (25%). Patients’ average age was 68 years. Primary tumors measured 4 cm in average diameter and the majority were squamous cell carcinoma of the usual (67%) or verrucous type (15%). Primary epithelial abnormalities found were squamous intraepithelial lesions, metaplasias and microglandular hyperplasias. Urethral squamous intraepithelial lesions of high grade was found in six patients and of low grade in eight cases. Squamous metaplasia, seen in 69 cases, was the most frequent finding. Metaplasias were classified as nonkeratinizing and keratinizing. Nonkeratinizing metaplasias (57 cases) were variegated in morphology: simplex (26 cases), hyperplastic (12 cases), clear cell (11 cases) and spindle (8 cases). Keratinizing metaplasias (12 cases) showed hyperkeratosis and were more frequently associated with verrucous than nonverrucous penile squamous cell carcinoma. Microglandular hyperplasia was present in eight cases. Lichen sclerosus was associated with simplex squamous metaplasia in four cases. Despite the large size of the primary tumors, direct urethral invasion by penile carcinoma was present in only 25% of the cases. The presence of precancerous lesions in urethra of patients with penile carcinoma indicates urethral participation in the pathogenesis of penile cancer. Simplex squamous metaplasia is a common finding probably related to chronic inflammation. Keratinizing and hyperplastic squamous metaplasias may be important in the pathogenesis of special types of penile carcinomas such as verrucous carcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Urethral and penile epithelia and their corresponding neoplasms are considered anatomically, embryologically and pathogenetically different1, 2, 3 and accordingly urethral neoplasms are usually described with urothelial lesions.4 However, the majority of primary tumors arising in the anterior urethra are of squamous type, and many are HPV-related, whereas those of the posterior urethra are transitional, non-HPV-related and similar to homologous lesions in the urinary tract.5, 6 These observations are consistent with the different anatomic features found at both sites. The posterior urethra is lined by a transitional epithelium, and the anterior urethra by a distinct and not-well-studied epithelium composed of a single layer of columnar cells at the surface, and a stratified or pseudostratified epithelium of small cells with round nuclei at the base. Patches of squamous epithelium has been described in this segment.4 The fossa navicularis, a distal saccular expansion of the urethra contiguous to the meatus, is lined by nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium and it is similar and continuous to the epithelium covering the penile glans. The anterior urethra and penile epithelia may be more closely related than previously thought. In fact, urethral carcinomas may involve the superficial epithelium of the glans penis, and conversely, carcinomas of the glans penis may compromise the urethra in a continuous or discontinuous manner.7 Adenosquamous carcinoma of the penile surface may originate in multipotential mucin-producing cells located in the glans epithelium. These cells, derived from displaced urethral mucinous cells, are similar to those of urethral Littre glands.8 Focal presence of mucous cells within the perimeatal squamous epithelium of the glans has also been described as well as mucinous metaplasia of the glans and foreskin inner mucosae,4, 9, 10 indicating the potential of penile squamous epithelium for mucinous differentiation. After observing numerous cases of dysplastic urethral lesions in patients with surface penile squamous cell carcinoma, we decided to study the inter-relation between penile and urethral epithelia. We searched for, and documented, anterior urethral epithelial abnormalities and precancerous lesions in patients with penile cancer. We also documented direct urethral invasion by penile carcinoma in resected penectomies.

Materials and methods

Case Materials

From a group of 200 penectomies for squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed at the Instituto de Patologia e Investigacion and the Facultad de Ciencias Medicas, Asuncion Paraguay, 170 penectomy specimens were selected. A total of 30 specimens were excluded because of marked autolysis of urethral epithelium, usually associated with overnight fixation in formalin with a previous insertion of an intraurethral probe. There were 89 cases with distal urethra epithelial abnormalities. Two main sections were studied per case: longitudinal, from meatal to proximal urethra at the shaft level (just below the V-shaped insertion of albuginea and corpus cavernosum in the glans),11 and transversal, representing the cut section of the proximal urethral margin. The average length of urethra in the longitudinal section was of 2.5 cm.

Patients and Primary Penile Tumors

Age ranged from 36 to 87 years (median was 68 years of age). Primary penile cancers affected multiple contiguous sites in 56 cases (63%). The sites were glans, coronal sulcus and or foreskin. In 33 cases the glans was the only site involved (37%). Size of tumor ranged from 1.5 to 11 cm, median size of 4 cm. All tumors were squamous cell carcinomas and the distribution by subtypes was as follows: usual, 60 cases (67%); verrucous, 13 cases (15%); basaloid, 6 cases (7%); warty, 5 cases (5%) and papillary, NOS, 5 cases (5%). Tumors were well differentiated (12 cases), of moderate differentiation (35 cases) or poorly differentiated (42 cases). Node dissections were performed in 42 of 89 cases and nodal metastases were present in 24 patients.

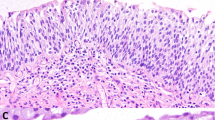

Histology of Normal Distal Urethral Mucosa

The distal part of the urethra—or fossa navicularis—measured 4–6 mm in length and showed a nonkeratinized squamous epithelium often with clear cytoplasm. The remainder epithelium was homogeneous and composed of two types of cells: a single columnar cell layer on the surface, and underlying layer of stratified 4–15 cells, showing an eosinophilic basement membrane. The nuclei of these cells were small, round, ovoid or spindly, with open chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli. There were intra- or juxta-epithelial acinar glands with a central lumen, lined by columnar cells with basal nuclei whose dense granular eosinophilic cytoplasm occasionally intermixed with clear, vacuolated mucinous cells. Recesseses of the urethra (Morgagni's lacunae) were lined by paraurethral mucinous Littre glands.

There were histologic transitions from the intra- or juxta-epithelial glands with dense eosinophilic cytoplasm to more mucinous cells features observed in Littre glands. Primary lesions were defined as alterations restricted to the urethral epithelium. The abnormalities were classified as secondary when the urethral epithelium (proximal, mid-portion or distal) was directly infiltrated by penile squamous cell carcinoma. Any squamous epithelium found in sites other than the fossa navicularis was considered metaplastic. Squamous metaplastic epithelium thicker than 15 cell layers was considered hyperplastic. Nomenclature utilized for precancerous lesions, low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, was according to the WHO consensus meeting and a recent study.12, 13

Results

There were primary and secondary urethral lesions in 131 of 170 specimens (77%). Primary epithelial abnormalities were identified in 89 cases (52%). These abnormalities included squamous metaplasia, squamous intraepithelial lesion and microglandular hyperplasia. Some cases showed more than one epithelial abnormality. Secondary lesions were the result of direct penile cancer invasion of distal urethra and were present in 42 cases (25%).

Primary Abnormalities

Squamous metaplasia

It was the most commonly found lesion (69 cases). The majority were non-keratinizing (57 cases) and the features were variegated: simplex or usual type (Figure 1a), 26 cases, hyperplastic, 12 cases, clear cell, 11 cases and with spindle cell features, eight cases. Most cases of clear cell metaplasia showed a particular segmental distribution in small intraepithelial nests or islands surrounded by normal urethral epithelium (Figure 1b). Sometimes these clear islands had a polypoid configuration protruding into the urethral lumen. Two cases showed diffuse clear cell metaplasia of the urethral epithelium (Figure 1c) extending to Morgagni's lacunae (Figure 1d). Keratinizing or hyperkeratotic squamous metaplasia was observed in 12 cases. There was surface hyperkeratosis, often associated with hyperplasia (Figure 1e). The hyperkeratotic squamous hyperplasia was associated in four cases with verrucous squamous cell carcinomas of the penis. In four specimens, in addition to squamous metaplasia, there were stromal changes consistent with lichen sclerosus (Figure 2). The lesions were extensions of lichen sclerosus affecting the glans penis.

Squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL)

In 14 cases the urethral epithelium showed focal atypical intraepithelial changes. In low-grade SIL (eight cases), the atypical cells involved the lower half of the epithelium (Figure 3). In high-grade SIL (six cases), the atypical cells involved the entire epithelial thickness (Figure 4a, b). The majority of the intraepithelial neoplastic lesions were discontinuous with the main penile invasive cancer, but a few were continuous.

We found no significant correlation of clinical and pathological features with the urethral epithelial abnormalities. Even though not statistically significant, there was a higher frequency of hyperkeratotic metaplasia in verrucous carcinomas as compared to other types, four of 13 in verrucous and eight of 76 in nonverrucous, 31 vs 10.5%, P-value 0.1 (Fisher's exact test).

Microglandular hyperplasia

Eight cases showed microglandular hyperplasia with an exaggerated number of intra- or juxta-epithelial glands with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (Figure 5). Microglandular hyperplasia was usually associated with chronic inflammation of the adjacent stroma.

Other changes

Less frequent epithelial changes were the loss of the superficial columnar cell layer (probably representing early metaplasia) in four cases, intraepithelial psammomatous calcification, two cases and condylomatous change with koilocytosis, one case. Frequently, the lamina propria showed a significant lymphocytic and especially plasma cell inflammatory infiltrate. In some cases, the chronic inflammation was so severe obliterating the normal histological architecture or producing ulceration of the urethral epithelium.

Secondary Lesions

Direct extension of invasive penile squamous cell carcinoma to urethra was found in 42 cases (25%) (Figure 6). The involvement was at the distal perimeatal urethra in half of the cases. The proximal and mid-urethra were compromised in 25% of the cases each. Usually, there was epithelial ulceration secondary to tumor invasion. Very rarely the obliteration of the urethral lumen was complete. Secondary involvement of urethral surface or juxta-epithelial glands simulated on cross-sections primary intraepithelial lesions. The abrupt presence of a high-grade neoplasm (often keratinizing) within the epithelia, without a gradual transition from low to high grade was typical of a secondary lesion. The transition from ‘intraepithelial’ to invasive areas could be more easily traced in the longitudinal sections.

Discussion

The finding of intraepithelial precancerous lesions in penile urethra of patients with penile squamous cell carcinoma indicates that the urethra participates either as a mechanical pathway of penile cancer progression in a continuous manner or as an independent site of primary tumor growth in discontinuous lesions. This observation suggests that penile and urethral mucosa represent one related field prone to malignant transformation and that a close relationship exists between tissues otherwise considered to belong to different anatomical compartments. This hypothesis is supported by the histological differences among the various urethral segments and their corresponding neoplasms and by the morphological similarities of some anterior urethral and penile tumors. In fact, there are two conflicting embryological explanations of the differentiation of the distal urethra: the ectodermal ingrowth theory (the distal urethra originates in the ectoderm, penetrating from glans to urethra) and the endodermal differentiation theory (distal urethra is formed by differentiation of endodermal tissues from urethra to glans).3

Independently of the embryogenesis, there are anatomical differences between the epithelium of the anterior urethra and the classical transitional urothelium of posterior urethra and the urinary tract. In the pendulous urethra, the surface cell layer is columnar without the ‘umbrella’ cells noted in bladder urothelium and prostatic urethra. In addition to the columnar cells, the penile urethral epithelium is composed of 4–15 stratified layers of uniform small cells, usually categorized as stratified or pseudostratified columnar epithelium. The distinctive epithelium appears to be related to the squamous rather than to the transitional urothelium. This would explain the high frequency of squamous metaplasias as well as the predominance of carcinomas of squamous type in the anterior urethra.4, 14, 15

The occasional involvement of the urethra by precancerous lesions should be taken into consideration when planning conservative, glans-sparing surgical procedures for limited primary squamous cell penile cancer.16 Often, in partial penectomies the surgeon leaves a long urethra to preserve urinary function increasing the risk of a positive margin of resection. Carcinoma in situ of urethral epithelium may be the only positive surgical margin of resection.7

The presence of lichen sclerosus in penile urethra of four patients, which was previously recognized to occur at this site,17 is noteworthy. The lesions were contiguous with lichen sclerosus of the glans and present adjacent to invasive carcinomas, adding more evidence to the notion that lichen sclerosus may be related to penile carcinogenesis18 and that the urethral epithelium and underlying stroma may also participate in the process.

The high frequency of squamous metaplasia, especially the simplex and hyperplastic types may be related to the chronic inflammation commonly present in association with penile cancer, after obstruction, or after secondary invasion of the urethra by the neoplasm. However, the metaplasia associated with hyperkeratosis may be related to some cancers, since these lesions are extensive, and may be continuous with low-grade variants of invasive squamous cell carcinoma occurring in the glans penis. The higher frequency of hyperkeratotic squamous metaplasia in cases of verrucous carcinoma suggests a relationship between these lesions. We observed resected verrucous carcinomas with urethral hyperkeratotic squamous metaplasia present at the surgical resection margin to recur as verrucous carcinomas. Simplex and hyperkeratotic squamous metaplasias have been described after long-term use of urethral stents, and after the administration of estrogen therapy.19, 20 The loss of the columnar superficial cell layer in some cases, like the bronchial loss of cilia in the respiratory epithelium of smokers, may represent the earliest stage of squamous metaplasia. Additional anatomical studies of the penile urethra in younger patients or a control study in adults using patients with and without cancer of the penis are necessary to rule out the possibility that some of the squamous metaplasias are not a normal component of the penile urethral epithelium.

The glands of the anterior urethra are also unique. There are two different types: the intra- or juxta-epithelial glands, with a dense eosinophilic cytoplasm and rounded basal nuclei, and the classical mucinous glands of the Littre with clear mucinous cytoplasm and basally compressed nuclei resembling pyloric glands of the gastrointestinal tract. Recently, Cohen et al21 demonstrated immunohistochemical expression of PSA in some periurethral glands, and on this basis postulated their relation with the prostate. We designated as microglandular hyperplasia the focal increased number of these glands. The finding of hyperplastic intra- or juxta-epithelial glands may be secondary to chronic inflammation.

Direct tumor invasion of urethra, noted in a fourth of the patients is not surprising considering the clinically advanced stage of the neoplasms in this group of patients. The higher frequency of parietal invasion and the rarity of intraluminal growth by invasive carcinoma explain the infrequency of urinary obstruction, despite the large size of these tumors and the common replacement of the glans by carcinoma. Direct invasion of the urethra by invasive carcinoma, especially when the tumor grows along the epithelial basement membrane, may occasionally cause a diagnostic problem with primary precancerous conditions. The abrupt presence of a high-grade neoplasm (often with keratin pearls) within the epithelia, without a gradual transition from low to high grade, the presence of tumor necrosis and the vicinity of an invasive cancer are characteristics of secondary involvement of the urethra.

In conclusion, the presence of urethral SILs of low and high grade in patients with penile carcinoma indicates that the urethra participates either as a mechanical pathway for cancer progression or an independent field prone to synchronic cancer transformation. Distal urethral epithelium is distinctive and different from the classical transitional epithelium of urinary tract, and may represent a modified or immature squamous epithelium. Typical squamous metaplasia is a common finding probably related to chronic inflammation. Keratinizing and hyperplastic squamous metaplasias may be important in the pathogenesis of a subset of penile and urethral carcinomas, especially verrucous carcinomas.

References

Barreto JE, Caballero C, Cubilla AL . Penis. In: Sternberg S (ed). Histology for Pathologists, 2nd edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, 1997, pp 1039–1047.

Herbut P . The urethra. In: Lea and Febiger (eds). Urological Pathology. Vol. I. Philadelphia, PA, 1952, pp 20–26.

Kurzrock EA, Baskin LS, Cunha GR . Ontogeny of the male urethra: theory of endodermal differentiation. Differentiation 1999;64:115–122.

Young RH, Srigley JR, Amin MB, et al. Tumors of the prostate gland, seminal vesicles, male urethra and penis, Atlas of Tumor Pathology Fascicle 3rd series ed. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Washington, DC, 2000.

Grussendorf-Conen EI, Deutz FJ, de Villiers EM . Detection of human papillomavirus-6 in primary carcinoma of the urethra in men. Cancer 1987;60:1832–1835.

Wiener JS, Liu ET, Walther PJ . Oncogenic human papillomavirus type 16 is associated with squamous cell cancer in male urethra. Cancer Res 1992;52:5018–5023.

Velazquez EF, Soskin A, Bock A, et al. Positive resection margins in partial penectomies: sites of involvement and proposal of local routes of spread of penile squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:384–389.

Cubilla AL, Ayala MT, Barreto JE, et al. Surface adenosquamous carcinoma of the penis. A report of three cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:156–160.

Fang AW, Whittaker MA, Theaker JM . Mucinous metaplasia of the penis. Histopathology 2002;40:177–179.

Val-Bernal JF, Hernandez-Nieto E . Benign mucinous metaplasia of the penis. A lesion resembling extramammary Paget's disease. J Cutan Pathol 2000;27:76–79.

Cubilla AL, Piris A, Pfannl R, et al. Anatomical levels: Important landmarks in penectomy specimens: a detailed anatomic and histologic study based on examination of 44 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1091–1094.

Cubilla AL, Meijer CJ, Young RH . Morphological features of epithelial abnormalities and precancerous lesions of the penis. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 2000;205:215–219.

Cubilla AL, Velazquez EF, Young RH . Epithelial lesions associated with invasive penile squamous cell carcinoma: a pathologic study of 288 cases. Int J Surg Pathol 2004;12:351–364.

Cupp MR, Malek RS, Goellner JR, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in primary squamous cell carcinoma of male urethra. Urology 1996;48:551–555.

Dalbagni G, Zhang ZF, Lacombe L, et al. Male urethral carcinoma: analysis of treatment outcome. Urology 1999;53:1126–1132.

Davis JW, Schellhammer PF, Schlossberg SM . Conservative surgical therapy for penile and urethral carcinoma. Urology 1999;53:386–392.

Barbagli G, Lazzeri M, Palminteri E, et al. Lichen sclerosis of male genitalia involving anterior urethra. Lancet 1999;354:429.

Velazquez EF, Cubilla AL . Lichen sclerosus in 68 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: frequent atypias and correlation with special carcinoma variants suggests a precancerous role. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:1448–1453.

Bailey DM, Foley SJ, McFarlane JP, et al. Histological changes associated with long term urethral stents. Br J Urol 1998;81:745–749.

Russell GA, Crowley T, Dalrymple JO . Squamous metaplasia in the penile urethra due to estrogen therapy. Br J Urol 1992;69:282–285.

Cohen RJ, Garrett K, Golding JL, et al. Epithelial differentiation of the lower urinary tract with recognition of the minor prostatic glands. Hum Pathol 2002;33:905–909.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Velazquez, E., Soskin, A., Bock, A. et al. Epithelial abnormalities and precancerous lesions of anterior urethra in patients with penile carcinoma: a report of 89 cases. Mod Pathol 18, 917–923 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800371

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800371

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Accuracy of MRI without intracavernosal prostaglandin E1 injection in staging, preoperative evaluation, and operative planning of penile cancer

Abdominal Radiology (2021)

-

The variable morphological spectrum of penile basaloid carcinomas: differential diagnosis, prognostic factors and outcome report in 27 cases classified as classic and mixed variants

Applied Cancer Research (2017)

-

Urethral carcinoma in situ: recognition and management

International Urology and Nephrology (2017)