Abstract

Few human tumors are collected such that RNA is preserved for molecular analysis. Completion of the Human Genome Project will soon result in the identification of more than 100,000 new genes. Consequently, increasing attention is being diverted to identifying the function of these newly described genes. Here we describe a multidisciplinary tumor bank procurement protocol that preserves both the integrity of tissue for pathologic diagnosis, and the RNA for molecular analyses. Freshly excised normal skin was obtained from five patients undergoing wound reconstruction following Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous neoplasia. Tissues treated for 24 hours with RNAlater™ were compared histologically and immunohistochemically to tissues not treated with RNAlater. Immunohistochemical stains studied included: CD45, CEA, cytokeratin AE1/3, vimentin, S-100, and CD34 on formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissue and CD45 staining of frozen tissue. Slides were blinded and evaluated independently by three pathologists. The histologic and immunohistochemical parameters of tissue stored in RNAlater were indistinguishable from tissue processed in standard fashion with the exception of S-100 stain which failed to identify melanocytes or Langerhan's cells within the epidermis in any of the RNAlater -treated tissues. Interestingly, nerve trunks within the dermis stained appropriately for S-100. Multiple non-cutaneous autopsy tissues were treated with RNAlater, formalin, liquid nitrogen (LN2), and TRIzol Reagent®. The pathologists were unable to distinguish between tissues treated with RNAlater, formalin, or frozen in LN2, but could easily distinguish tissues treated with TRIzol Reagent because of extensive cytolysis. RNA was isolated from a portion of the tissue treated with RNAlater and used for molecular studies including Northern blotting and microarray analysis. RNA was adequate for Northern blot analysis and mRNA purified from RNAlater -treated tissues consistently provided excellent templates for reverse transcription and subsequent microarray analysis. We conclude that tissues treated with RNAlater before routine processing are indistinguishable histologically and immunohistochemically from tissues processed in routine fashion and that the RNA isolated from these tissues is of high quality and can be used for molecular studies. Based on this study, we developed a multidisciplinary tumor bank procurement protocol in which fresh tissue from resection specimens are routinely stored in RNAlater at the time of preliminary dissection. Thus, precious human tissue can be utilized for functional genomic studies without compromising the tissue's diagnostic and prognostic qualities.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

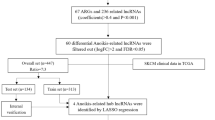

Human tumors are routinely excised in hospitals around the world, but few are collected in a way that adequately preserves RNA for molecular analyses. With the impending completion of the human genome project, increased attention is being diverted toward functional genomics, the main goal of which is the daunting task of assigning function to a multitude of newly described genes (1, 2). One rate-limiting step in the completion of human functional genomic experiments is the lack of high-quality human RNA. It has proven difficult to preserve the diagnostic and prognostic qualities of surgical tissue while at the same time maintaining the integrity of RNA within the sample for research. At many institutions, tissue obtained from surgical procedures is refrigerated for a variable period of time before a pathologist takes samples for histopathologic, cytopathologic, and other diagnostic studies. The RNA from surgical specimens processed in this fashion is often degraded by the time it is fresh-frozen or homogenized in RNA-preserving denaturants, rendering the specimens of variable use for experiments requiring intact RNA. Understandably, pathologists are concerned about providing fresh tissue samples for research purposes because of the potential loss of important diagnostic information that may be needed in the future. However, after sections have been taken by the pathologist, excess human tissue is retained in formalin for at least two weeks and is then discarded (3), which precludes further molecular genetic analysis. A dilemma exists: the surgical pathologist needs to maintain tissue histology for optimal patient care and the basic scientist requires adequately preserved RNA for functional genomic experiments. Most RNA-preserving solutions contain organic solvents and denaturing agents (e.g., phenol, guanidine, etc.) that destroy tissue integrity, precluding further histologic analysis of the tissue. An alternative to these solutions is necessary to preserve tissue integrity while still maintaining RNA quality within the sample. One potential option is RNAlater™ (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX), a solution that is known to preserve RNA in tissues, but has not been studied to determine its effect on tissue preservation. Here we describe a multidisciplinary tumor bank procurement protocol that preserves the integrity of the tissue for pathologic studies as well as the RNA for molecular analyses. Additionally, we demonstrate histo-molecular correlation between tumor histology and differential gene expression as identified by microarray analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Acquisition

Normal skin was obtained from five patients undergoing wound reconstruction following Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous neoplasia (2 male, 3 female; age range 66–85 y; mean age 77 y). Freshly excised normal skin tissue containing epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous adipose connective tissue was prepared as shown in the protocol (Fig. 1). Each skin sample was divided and half of the tissue was placed into RNAlater (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) for 24 hours at ambient temperature. The second half was cut into two pieces, one of which was fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours then routinely processed and embedded in paraffin, the other of which was frozen immediately in OCT medium (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA) at–20°C. After 24 hours in RNAlater, approximately 10% of the skin sample was retained and maintained at 4°C for two to six weeks before subsequent RNA isolation. The remaining 90% of this tissue was divided into two pieces, one of which was fixed in formalin, the other frozen in OCT medium as described above. Frozen and paraffin-embedded specimens were stained with H&E and CD45. Each paraffin-embedded tissue also was stained with CEA, cytokeratin AE1/3, vimentin, and S-100. Tissue from malignant melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma was obtained separately.

To evaluate the effect of RNAlater on tissues other than skin, autopsy material was obtained (the patient had expired approximately 17 hours before the autopsy). Samples of brain, thyroid, lung, heart, skeletal muscle, stomach, small and large intestine, pancreas, spleen, lymph node, prostate, liver, and tongue were treated with RNAlater, liquid nitrogen (LN2), or TRIzol Reagent® for 24 hours or three weeks. Formalin-treated tissues were used as a control. Following LN2, TRIzol Reagent, or RNAlater treatment, tissues were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. RNA was not isolated from autopsy tissue. [This study fulfilled all requirements of the University of Utah Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board.]

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and absolute ethanol, then rehydrated by successive immersions in 95% ethanol, 70% ethanol, and distilled water. Immunoperoxidase staining was performed on the Ventana ES instrument (Ventana medical systems, Tucson, AZ) using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex according to manufacturer recommendations. Primary antibody to S-100 (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, CA; diluted 1:700), vimentin (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, CA; diluted 1:200), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA; Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN; diluted 1:1000), CD34 (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA; diluted 1:200), cytokeratin AE1,3 (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN; diluted 1:1400), and CD45 (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, CA; diluted 1:50) proteins were applied and the immunostaining was developed using diaminobenzidine (3,3′-diaminobenzidine) as the chromogen and counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. For frozen tissues, five micron frozen sections were cut and applied to silanized glass microscope slides (Superfrost/Plus, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), two sections per slide, then fixed in acetone. Immunostaining for CD45 protein was performed on the Ventana ES Instrument as described above.

A sample of melanoma was treated with RNAlater then formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded and stained with HMB-45. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized as above. High-temperature antigen retrieval was performed using DAKO Target Retrieval Solution (DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions, then rinsed in potassium-free phosphate buffered saline to remove the detergent solution. The sections were then immersed in 3% H2O2 for 15 minutes at room temperature. The sections were incubated in 10% normal human serum (Scantibodies, Santee, CA), 5% normal goat serum (Biodesign International, Kennebunk, ME), 1% bovine serum albumin, fraction V (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) in potassium-free PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature to block non-specific sites. The sections were incubated with HMB45 antibody (DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, CA) diluted 1:100 in blocking solution overnight at room temperature. The following day, the sections were incubated with secondary biotinylated goat anti-mouse antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) diluted 1:1000 in 5% normal goat serum, 1% BSA in potassium-free PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature followed by Elite ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Visualization was accomplished with diaminobenzidine (3,3′-diaminobenzidine; Vector Labs) for five minutes at room temperature and rinsed with deionized distilled water. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in a series of alcohols to xylene then cover-slipped.

Statistical Analysis

Tissues treated for 24 hours with RNAlater were compared histologically and immunohistologically to tissues processed immediately without RNAlater treatment (Fig. 2). Specimens were either frozen in OCT medium (Sakura-Finetek U.S.A., Inc., Torrance, CA) or formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded for routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 2). Specific tumor markers were selected for their ability to stain normal cutaneous structures. Three pathologists (S.R.F., C.M.C., and J.A.H.) scored H&E stained slides on three histologic parameters: nuclear detail, cytoplasmic detail, and overall preservation. A coding system for slide labels prevented the pathologists from identifying how the tissues had been processed. For immunostained slides, the parameters judged were: staining intensity, definition, and background intensity. Each slide was also assessed for overall diagnostic adequacy. Every parameter was assigned a numeric value of 1 (defined as poor or inadequate) or 2 (defined as good-to-excellent or adequate). Each pathologist evaluated all ninety slides blindly and independently. Scores were analyzed using Chi square comparing RNAlater versus non-RNA later treated tissues.

Specimens preserved in RNAlater maintain histologic integrity. Representative tissues shown in panels A, C, E, and G were incubated in RNAlater for 24 hours before processing; tissues in panels B, D, F, and H were processed immediately. A and B, equivalent H&E staining of frozen tissue sections; C and D, equivalent H&E staining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections; E and F, CD45 immunostain on frozen tissue showing equivalent staining of lymphocytes; G and H, cytokeratin AE1/3, immunostain of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue, showing equivalent staining of sweat duct epithelium.

RNA Preparation and Use

All RNAlater-treated skin tissues were maintained in RNAlater at room temperature for 24 hours and then at 4°C for 2–6 weeks before RNA was purified. All RNAs were purified by the standard TRIzol protocol following immediate homogenization directly in the TRIzol Reagent (4). [The HCI Microarray Resource has determined that the TRIzol purification method provides excellent RNA template for microarray analysis (Huntsman Cancer Institute Microarray Resource, personal communication, 1999).] To establish that the RNA purified from RNAlater -treated tissues was adequate for microarray analysis, two cutaneous tumors, a sclerosing basal cell carcinoma, and a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) were selected for comparison. Each tissue was stored in RNAlater for 24 hours at room temperature and then at 4°C for two weeks. The tissue was minced in RNAlater and homogenized (Kika-Werk Ultra-Turax, Tekmar, Cincinnati, OH) in TRIzol Reagent. Of interest, we have successfully used RNAlater treated tissue homogenates for PCR reactions suggesting that the DNA is intact. Total RNA was purified using the standard TRIzol method (4). Oligotex (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) was used to obtain poly A+ enriched RNA for use on the microarray. Poly A+ RNA was reverse transcribed and the BCC-derived RNA was labeled with Cy3-dCTP (green) while the SCC-derived RNA was labeled with Cy5-dCTP (red) as previously published (5). The labeled cDNA was hybridized to a glass microscope slide harboring 4608 clones (in duplicate) and imaged by a Generation III Molecular Dynamics laser scanner (Sunnyvale, CA). Numeric analysis was performed using Array Vision quantification software (version 4.15, Imaging Research). Clones demonstrating a 2-fold or greater numeric change were included in Table 1. False positive clones were excluded by visual inspection and all clones were confirmed by sequencing. Microarray results were confirmed by Northern blot analysis as described previously (5) using clones encoding human monokine induced by gamma interferon (MIG, shown in Fig. 6A) and KIAA0941. Northern blots were also performed on normal skin specimens (Fig. 6C)

Molecular analyses of RNA A, representative panel from the expression microarray is shown. The squamous cell carcinoma mRNA is labeled with Cy5-dCTP (red) and the basal cell carcinoma mRNA is labeled with Cy3-dCTP (green). mRNA purified from RNAlater-treated tissues provided excellent templates for microarray analysis. B, Northern blot (performed as described previously [5]); lane 1, 1 μg squamous cell carcinoma poly A+-enriched RNA; lane 2, 1 μg basal cell carcinoma poly A+-enriched RNA (same RNA samples used on the microarray); the Northern blot was probed with a cDNA encoding the monokine induced by gamma interferon (MIG) that is also shown as a green spot on the microarray above. GAPDH expression is shown below as a loading control in panels B and C. Northern blot analysis confirms differential expression of MIG in these samples. C, Northern blot of the same gel shown in Fig. 4, probed with KIAA0941, a gene differentially expressed in the previously described microarray experiment. The transcript is clearly visible in RNA purified from RNAlater-treated tissues, but not in the RNA isolated by the same method from flash-frozen tissue. Although KIAA0941 was differentially expressed in the two tissues compared by microarray, the pattern of differential expression was not maintained in additional patients' tumors.

RESULTS

Preservation of Histologic and Immunohistologic Integrity

Ninety slides were evaluated blindly and independently by three pathologists (S.R.F., C.M.C., and J.A.H.). There was no significant intra-observer variability except for the CD45 stain (paraffin and frozen tissue, P = 0.0212 and P = less than 0.001, respectively, favoring RNAlater in one of three observers). Scores were analyzed using Chi-square, comparing RNAlater versus non-RNAlater -treated tissues. The histologic and immunohistochemical parameters and overall diagnostic adequacy of tissue stored in RNAlater were indistinguishable (P = 0.07–1.00) from tissue processed in the standard fashion, with the exception of the S-100 stain. Nerve trunks within the S-100-stained dermis stained normally, but epidermal melanocytes and Langerhan's cells could not be identified in any of the RNAlater -treated tissues. There was no difference in the staining characteristics of RNAlater -treated tissues after two months at 4°C (data not shown). As an alternative to S-100, staining for HMB45 in a sample of malignant melanoma treated with RNAlater was performed and showed appropriate staining characteristics (data not shown). For autopsy material, the pathologists were unable to distinguish between tissues treated with formalin, RNAlater, or LN2 at 24 hours or three weeks, but were easily able to identify tissues treated with TRIzol Reagent because of extensive cytolysis and absence of nuclei, even after only 24 hours in this reagent (Fig. 3). These data demonstrate that specimens can be stored in RNAlater and safely retrieved by the pathologist for further examination if necessary.

Preservation of RNA Integrity

In order to confirm that RNAlater treatment preserved the integrity of RNA, total RNA was isolated from RNAlater-treated human skin (TRIzol Reagent, Life Technologies). Intact RNA has been purified from numerous RNAlater-treated tissues, including malignant melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans that were evaluated for histologic and immunohistochemical integrity (data not shown). A representative group of normal and malignant tissue RNAs are shown in an ethidium bromide-stained formaldehyde gel (Fig. 4). Lane 1 of Fig. 4 shows the typical, degraded status of RNA purified from normal skin that was flash-frozen in surgical pathology after 30 minutes at room temperature during dissection of the specimen. All RNAlater-treated tissues were maintained in RNAlater at room temperature for 24 hours and then at 4°C for 2–6 weeks before RNA was purified using TRIzol Reagent (4). RNAlater-treated tissues in lanes 2–6 have RNA with distinct ribosomal bands and a smear of high molecular weight RNA, showing that RNA obtained from the RNAlater-treated tissues is well preserved.

Minimal degradation of RNA from normal and malignant tissue Ethidium bromide stained 1.2% agarose/3% formaldehyde gel, digitized using ImageQuant 5.0 (Molecular Dynamics). Lane 1, RNA from normal skin, fresh frozen by surgical pathology and purified using the standard TRIzol Reagent protocol.(4) This sample is representative of numerous unsuccessful attempts that have been made to obtain intact RNA from human surgical samples (data not shown); lanes 2–6, RNA purified from tissues maintained in RNAlater for 2 weeks at 4°C and purified using the standard TRIzol Reagent protocol; lanes 2–4, RNA from normal skin; lane 5, RNA from squamous cell carcinoma from the same patient shown in lane 3; lane 6 RNA from basal cell carcinoma from the same patient as lane 4. Intact ribosomal bands and high-molecular weight RNAs are clearly visible in RNAlater treated samples and markedly decreased in the fresh frozen specimen.

We next sought to establish that the RNA purified from RNAlater-treated tissues was adequate for microarray analysis. Two cutaneous tumors, a sclerosing basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), were selected for comparison (Fig. 5).

Pathologic features of tumors used in microarray analysis A sclerosing BCC and well-differentiated SCC preserved in RNAlater were selected as sources of RNA for microarray analysis. The pathologic features of the tumors are shown at 400 × power and listed above. Mitotic figures, apoptotic cells, lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrates, keratinization, and intercellular bridges are marked as indicated. The BCC is a less differentiated, more actively dividing tumor.

A representative panel from the microarray is shown in Fig. 6A and several clones demonstrating a 2-fold or greater change are identified. Green spots represent mRNAs more highly expressed in the BCC whereas red spots represent mRNAs more highly expressed in the SCC. Yellow spots identify mRNAs expressed at the same level in both tumors. RNA obtained from RNAlater-treated tissues was indistinguishable as a template from other RNAs used at the Huntsman Cancer Institute Microarray Resource.

To prove that RNA from RNAlater-treated tissues was intact and to confirm microarray experimental results, Northern blot analysis was performed. Fig. 6B shows a Northern blot of the poly A+ enriched RNAs used in the microarray experiment above while Fig 6C shows a Northern blot of the gel seen in Fig. 4 Two clones were selected: one clone differentially upregulated in the BCC (MIG) and one in the SCC (KIAA0941). To verify the microarray results, both clones were used as a probe on the Northern blot; in Fig. 6B, the results of MIG are shown. The 3.9-fold increase in MIG expression in the BCC sample (Fig. 6A, microarray result) was confirmed as a 38-fold increase on Northern blot analysis (Fig. 6B). Thus, RNA of at least 2500 base pairs was intact and interpretable by Northern blot analysis, and the Northern blot analysis also confirmed the microarray results (data not shown for KIAA0941 result). KIAA0941 was used to probe the Northern blot in Fig. 6C to determine whether the differential expression seen between the BCC and SCC samples used in the microarray was present in additional patient samples. The KIAA0941 gene did not show significantly different gene expression in the additional normal and malignant tissues on the gel, suggesting that the differential gene expression seen in the KIAA0941 in the microarray experiment was specific to those two tumors. This illustrates the importance of confirming microarray results obtained from single tumor comparison and highlights the need for multiple tissue samples for screening potential genes of interest. Lane 1 does not show a clearly discernable band, confirming the degradation of the RNA obtained from the flash-frozen specimen. In summary, these data demonstrate that the RNA obtained from RNAlater-treated tissues provides investigators with high quality RNA for molecular analyses.

DISCUSSION

Functional genomic experiments represent the next bridge between basic science research and applied clinical medicine. Increased availability of human tissue and human RNA for these studies will dramatically improve the rate at which these experiments can be completed. Our data (6) demonstrate that the RNA from human tissues and tumors can be preserved for molecular analyses and that the histologic integrity of the specimen can be simultaneously maintained after immersion in RNAlater. The implications of our findings are that surgical specimens can be effectively preserved for both molecular and pathologic analyses without compromising the care of the patient. This is the first report, to our knowledge, utilizing this reagent in the surgical pathology laboratory. Others have used RNAlater to fix and preserve RNA suitable for expression and genotype analysis of flow cytometrically purified populations of neoplastic cells from tissues in vivo (7).

In summary, we have shown that RNAlater effectively preserves histologic and immunohistochemical properties of cutaneous and non-cutaneous tissues. Moreover, in comparison of multiple RNAlater-treated tissues obtained at autopsy with other methods of RNA preservation such as the gold standard, LN2, and denaturing agents such as TRIzol Reagent, we found that the reviewing pathologists were unable to distinguish tissues treated in RNAlater from those fixed in formalin or fresh frozen in LN2. These results demonstrate that a portion of tissue obtained during the initial dissection of a surgical specimen may be stored in RNAlater and retrieved if necessary for histologic and immunohistologic examination. There are several additional advantages in using RNAlater. Fresh-frozen tissue samples are less than optimal for both clinicians and scientists. For the scientist, frozen tissue is more difficult to manipulate and homogenize than non-frozen specimens. For the pathologist, frozen tissue requires thawing before dissection, leading to RNA degradation. Maintaining the tissue in RNAlater eliminates the need to thaw RNA-preserved tissues. Moreover, LN2 may not be readily available in the surgical pathology laboratory whereas RNAlater is a safe, non-toxic solution that is stored at ambient temperature. Demonstrating that a specimen placed in RNAlater is still accessible for pathologic interpretation has enhanced specimen triage, especially when the amount of tissue is limited.

The first step in establishing that RNAlater was not disruptive to histopathological or molecular analyses was to compare the tissues treated with RNAlater to tissues processed in the standard way. As illustrated in Fig. 2, there were no discernable differences between H&E frozen or paraffin-embedded sections. Three pathologists found no differences in any of the RNAlater-treated H&E-stained specimens or with immunohistochemical markers for CEA, CD45, CD34, or AE1/3. All of the RNAlater- treated specimens were adequate for diagnostic purposes. The exception to this finding was with the S-100 immunostain, which stained nerve fibers adequately, but failed to stain melanocytes or Langerhan's cells. This differential staining is seen in tissues treated with an aqueous solution (such as RNAlater) before formalin fixation (Dako Corporation, personal communication, 1999). The reason for this differential staining is unclear but may reflect solubility differences between different isoforms of the S-100 antigen on melanocytes, Langerhan's cells and nerve tissue, but this was not tested directly. We hypothesize that S-100 protein, named for its solubility in saturated ammonium sulfate solution (8), is being solubilized by the aqueous RNAlater solution. We caution that other soluble antigens that require formalin fixation before immunostaining may not stain appropriately after RNAlater treatment. The lack of S-100 staining is unfortunate for investigators who might want to follow this marker experimentally. New S-100 antibodies for frozen tissue will soon be available (Dako Corporation, personal communication, 1999) so that it may be possible to optimize staining conditions for this antigen in the future. In the meantime, S-100 staining should be performed on tissue that has not been stored in RNAlater. For some types of malignant melanoma, HMB45 may be used as an alternative melanocytic marker.

We also sought to show that non-cutaneous tissues were also well preserved in RNAlater. As can be seen in Fig. 3, RNAlater preserved histology in other tissues obtained at autopsy. Perhaps more importantly, other RNA-preserving agents such as TRIzol Reagent destroy histology, making some of the tissues impossible to identify.

The second essential component of our study was to demonstrate that RNAlater-treated tissue specimens maintained the integrity of RNA required for molecular analyses. The RNA isolated from RNAlater - preserved tissues is intact by visual examination of ethidium bromide-stained denaturing gels, by Northern blot analysis, and by expression microarray analysis (Figs. 4 and 6). Differentially expressed genes identified by microarray analysis were also confirmed by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 6). It should be noted that the most likely cause of RNA degradation in the flash-frozen sample (lane 1, Fig. 6) was the time period that the sample spent in surgical pathology before freezing. It is unlikely that the degradation occurred during homogenization because it was pulverized in a frozen state immediately before homogenization in TRIzol Reagent. Before the initiation of the tissue procurement protocol depicted in Fig. 7, RNA degradation was the rule rather than the exception.

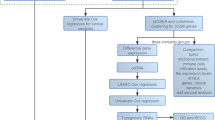

Multidisciplinary tumor bank procurement protocol Schematic illustration of our standard tumor bank procurement protocol incorporating RNAlater preservation methodology. The implementation of this multidisciplinary approach, utilizing an agent capable of preserving RNA has maximized our use of human surgical specimens without compromising patient care.

The microarray analysis comparing RNAs purified from a sclerosing BCC and a well-differentiated SCC confirmed the adequacy of our RNA templates and simultaneously identified some intriguing differentially regulated genes (Fig. 5 and Table 1). RNAlater preserved RNAs provided templates for microarray analysis that were indistinguishable from 1) RNA obtained from cultured cells treated directly with TRIzol Reagent and 2) tissues that were immediately frozen and then homogenized in TRIzol.

Not only was the RNA an excellent template, the microarray analysis of these RNAs demonstrated histo-molecular correlation. Many of the differentially regulated genes identified by microarray analysis (Table 1) are expected, based on the observed histopathology of the tumors and published functions of the differentially expressed genes. These findings provide preliminary evidence for good histopathologic correlation between human tumor pathology and microarray analysis. For example, the most prominent histological differences observed in these two tumors (Fig. 5) are (a) the more differentiated status of the squamous cells versus the basal cells (as demonstrated by keratinization and prominent desmosomal attachments in the SCC) and (b) the rate of proliferation of the tumor as demonstrated by the higher mitotic rate of the BCC. Desmoglein 1, a desmosomal protein expressed primarily in the differentiated layers of the epidermis (9) showed a 2.3-fold higher expression in the SCC versus the BCC, corresponding to the differentiation status of the tumors. Stathmin is a cytosolic phosphoprotein implicated as a relay protein that integrates various signaling pathways with cell proliferation and differentiation. It is expressed at higher levels in rapidly proliferating, less differentiated cells (10). Our microarrays show 4.0-fold higher expression in the BCC relative to the SCC, correlating to the higher rate of proliferation and less differentiated status in the BCC. To our knowledge, stathmin expression has not been previously reported in normal or malignant cutaneous lesions.

In addition to the expression of several expected individual genes, two specific expression patterns were identified, namely genes regulated by either retinoids or interferons, or both (Table 1). Interestingly, retinoids and interferons potentiate each other in vitro (11) and have been used together to treat squamous cell carcinomas (12). Because retinoids are clearly involved in the programmed differentiation of keratinocytes (13), it makes sense that many retinoid-inducible genes are differentially expressed in tissues with dissimilar levels of differentiation. Interestingly, interferon-regulated genes have recently been shown by Karpf et al (5) to be involved in the cellular response to 5′-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, an inhibitor of DNA methyltransferase. These findings warrant investigation of the role of interferon-regulated genes in the differentiation status of cutaneous malignancies. It will be interesting to see if any of the recently discovered genes or EST's identified in this microarray prove to be part of these same pathways.

In conclusion, the preservation of tissue RNA has contributed to the success of this protocol at our institution. The key to successful procurement of tissues for studies involving RNA is the use of a multidisciplinary collaborative approach (Fig. 7). Clearly, the tumor bank or clinical investigator must identify cases of potential interest. In consultation with a surgical pathologist, tissue specimens may be collected rapidly at the time of a surgical procedure, and specimens may be placed in RNAlater as quickly as possible, provided there are adequate tissue samples for diagnostic and prognostic purposes. The usual dissection and processing protocols can then be followed, obtaining tissue for electron microscopic studies, tissue banking, cytogenetic studies, tissue culture, and so forth. Tissue placed in RNAlater may be held for at least eight weeks without compromising tissue histology or immunohistochemical studies. If the pathologist does not need the tissue for diagnostic purposes, it may be delivered to the basic scientist for molecular studies, thereby making the most efficient use of this limited and valuable resource.

References

Borrebaeck CAK . Tapping the potential of molecular libraries in functional genomics. Immunol Today 1998; 19: 524–7.

Fields S, Kohara Y, Lockhart DJ . Functional genomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96: 8825–6.

College of American Pathologists. Commission on Laboratory Accreditation Inspection Checklist, Anatomic Pathology, p. 108, 1999.

Chomczynski P . A reagent for the single-step simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA and proteins from cell and tissue samples. Biotechniques 1993; 15: 532–4, 536–7.

Karpf AR, Petersen PW, Rawlins JT, Dalley BK, Yang Q, Albertsen H, et al. Inhibition of DNA methyltransferase simulates the expression of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1,2 and 3 genes in colon tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96: 14007–12.

Florell SR, Coffin CM, Holden JA, Zimmerman J, Summers BK, Gerwels JW, et al. Preservation of RNA for functional genomic studies: a multidisciplinary tumor bank protocol [abstract]. Mod Pathol 2000; 13: 222A.

Barrett MT, Glogovac J, Porter P, Reid BJ, Rabinovitch PS . High yields of RNA and DNA suitable for array analysis from cell sorter purified epithelial cell and tissue populations. Nat Genet 1999; 23: 32–3.

Cochran AJ, Wen DR . S-100 protein as a marker for melanocytic and other tumors. Pathology 1985; 17: 340–5.

Konohana A, Konohana I, Roberts GP, Marks R . Biochemical changes in desmosomes of bovine muzzle epidermis during differentiation. J Invest Dermatol 1987; 89: 353–7.

Doye V, Kellermann O, Buc-Caron MH, Sobel A . High expression of stathmin in multipotential teratocarcinoma and normal embryonic cells versus their early differentiated derivatives. Differentiation 1992; 50: 89–96.

Chelbi-Alix MK, Pelicano L . Retinoic acid and interferon signaling cross talk in normal and RA-resistant APL cells. Leukemia 1999; 13: 1167–74.

Roth AD, Morant R, Alberto P . High dose etretinate and interferon-alpha—a phase I study in squamous cell carcinomas and transitional cell carcinomas. Acta Oncol 1999; 38: 613–7.

Jetten AM . Multi-stage program of differentiation in human epidermal keratinocytes: regulation by retinoids. J Invest Dermatol 1990; 95: 44S–6S.

Luster AD, Unkeless JC, Ravetch JV . Gamma-interferon transcriptionally regulates an early-response gene containing homology to platelet proteins. Nature 1985; 315: 672–6.

Johnson WE, Jones NA, Rowlands DC, Williams A, Guest SS, Brown G . Down-regulation but not phosphorylation of stathmin is associated with induction of HL60 cell growth arrest and differentiation by physiological agents. FEBS Lett 1995; 364: 309–13.

Farber JM . HuMig: a new human member of the chemokine family of cytokines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1993; 192: 223–30.

Inazumi T, Tajima S, Nishikawa T, Kadomatsu K, Muramatsu H, Muramatsu T . Expression of the retinoid-inducible polypeptide, midkine, in human epidermal keratinocytes. Arch Dermatol Res 1997; 289: 471–5.

Lingen MW, Polverini PJ, Bouck NP . Retinoic acid and interferon alpha act synergistically as antiangiogenic and antitumor agents against human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 5551–8.

Hsu HC, Tsai WH, Chen PG, Hsu ML, Ho CK, Wang SY . In vitro effect of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor and all-trans retinoic acid on the expression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Eur J Hematol 1999; 63: 11–8.

Shan B, Vazquez E, Lewis JA . Interferon selectively inhibits the expression of mitochondrial genes: a novel pathway for interferon-mediated responses. EMBO J 1990; 9: 4307–14.

Gaemers IC, Van Pelt AM, Themmen AP, De Rooij DG . Isolation and characterization of all-trans-retinoic acid-responsive genes in the rat testis. Mol Reprod Dev 1998; 50: 1–6.

Rasmussen UB, Wolf C, Mattei MG, Chenard MP, Bellocq JP, Chambon P, et al. Identification of a new interferon-alpha-inducible gene (p27) on human chromosome 14q32 and its expression in breast carcinoma. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 4096–101.

Diaz A, Jimenez SA . Interferon-gamma regulates collagen and fibronectin gene expression by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 1997; 29: 251–60.

Vasaturo F, Modesti A, Scarpa S . Interferon gamma modifies fibronectin and laminin synthesis in human neuroblastoma cell lines. Int J Oncol 1998; 12: 895–8.

De-Luca LM, Scita G . Ha-ras oncogene transformation abolishes retinoic acid-induced reduction of intracellular fibronectin. Braz J Med Biol Res 1996; 29: 1127–31.

Shanker G, Sawhney R . Retinoic acid: identification of specific receptors through which it may mediate transcriptional regulation of fibronectin gene in bovine lens epithelial cells. Cell Biol Int 1996; 20: 613–9.

Chou JY, Hugunin PE, Mano T . Control of placental protein production by retinoic acid in cultured placental cells. In Vitro 1983; 19: 571–5.

Shanker G, Sawhney R . Retinoic acid: identification of specific receptors through which it may mediate transcriptional regulation of fibronectin gene in bovine lens epithelial cells. Cell Biol Int 1996; 20: 613–9.

Chou JY, Hugunin PE, Mano T . Control of placental protein production by retinoic acid in cultured placental cells. In Vitro 1983; 19: 571–5.

Acknowledgements

We thank Edward R. Ashwood, M.D., and Lynn K. Pershing, PhD., for help with statistical analysis and Kurt H. Albertine, Ph.D. and William Carroll, M.D. for help with incorporating our technique into the Huntsman Cancer Institute and Primary Children's Hospital Tumor Bank Protocols. This work was supported by the Charles A. Oclassen Dermatology Foundation Research Fellowship, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, The Huntsman Cancer Institute and its Microarray Resource, and Ambion, Inc., who provided the RNAlater used in this study as well as financial support for histologic and immunohistologic staining. A portion of this study was presented orally at the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology (USCAP) Annual Meeting, Techniques Section, in New Orleans, Louisiana, on 27 March 2000. Ambion, Inc. provided financial support for travel arrangements for one of the presenters (S.R.F.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Florell, S., Coffin, C., Holden, J. et al. Preservation of RNA for Functional Genomic Studies: A Multidisciplinary Tumor Bank Protocol. Mod Pathol 14, 116–128 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880267

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880267

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Expression of Nuclear Division Cycle 80 Complex Genes in Ovarian Cancer and Correlation with the Clinicopathological Features and Survival Outcomes

Indian Journal of Gynecologic Oncology (2024)

-

High HSPB1 expression predicts poor clinical outcomes and correlates with breast cancer metastasis

BMC Cancer (2023)

-

Test of the FlashFREEZE unit in tissue samples freezing for biobanking purposes

Cell and Tissue Banking (2023)

-

Comprehensive proteome and phosphoproteome profiling shows negligible influence of RNAlater on protein abundance and phosphorylation

Clinical Proteomics (2019)

-

A comprehensive pipeline for translational top-down proteomics from a single blood draw

Nature Protocols (2019)