Abstract

This paper examines the professional and scientific views on the principles, techniques, practices, and policies that impact on the population genetic screening programmes in Europe. This paper focuses on the issues surrounding potential screening programmes, which require further discussion before their introduction. It aims to increase, among the health-care professions and health policy-makers, awareness of the potential screening programmes as an issue of increasing concern to public health.

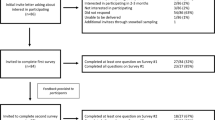

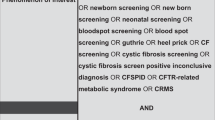

The methods comprised primarily the review of the existing professional guidelines, regulatory frameworks and other documents related to population genetic screening programmes in Europe. Then, the questions that need debate, in regard to different types of genetic screening before and after birth, were examined. Screening for conditions such as cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, familial hypercholesterolemia, fragile X syndrome, hemochromatosis, and cancer susceptibility was discussed. Special issues related to genetic screening were also examined, such as informed consent, family aspects, commercialization, the players on the scene and monitoring genetic screening programmes. Afterwards, these questions were debated by 51 experts from 15 European countries during an international workshop organized by the European Society of Human Genetics Public and Professional Policy Committee in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 19–20, November, 1999. Arguments for and against starting screening programmes have been put forward. It has been questioned whether genetic screening differs from other types of screening and testing in terms of ethical issues. The general impression on the future of genetic screening is that one wants to ‘proceed with caution’, with more active impetus from the side of patients' organizations and more reluctance from the policy-makers. The latter try to obviate the potential problems about the abortion and eugenics issues that might be perceived as a greater problem than it is in reality. However, it seems important to maintain a balance between a ‘professional duty of care’ and ‘personal autonomy’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Committee for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism: Genetic screening: programs, principles and research. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1975.

The Nuffield Trust Genetics Scenario Project: Genetics and Health. Policy issues for genetic science and their implications for health and health services. London: The Stationery Office; 2000.

WHO Wilson JMG, Jungner G : Principles and practice of screening for disease. Geneva: WHO; 1968.

Goel V : Appraising organised screening programmes for testing for genetic susceptibility to cancer. BMJ 2001; 322: 1174–1178.

Hoedemaekers R, ten Have H, Chadwick R : Genetic screening: a comparative analysis of three recent reports. J Med Ethics 1997; 23: 135–141.

Stranc L, Evans J : Issues relating to the implementation of genetic screening programs. in Knoppers BM (ed): Socio-ethical issues in human genetics. Montreal: Les Editions Yvon Blais Inc.,; 1998, pp 49–105.

Alderson P, Aro AR, Dragonas T et al: Prenatal screening and genetics. Eur J Public Health 2001; 11: 231–233.

Austoker J : Gaining informed consent for screening. BMJ 1999; 319: 722–723.

General Medical Council: Seeking patients' consent: the ethical considerations. London: General Medical Council; 1999.

Delvaux I, van Tongerloo A, Messiaen L et al: Carrier screening for cystic in a prenatal setting. Genet Test 2001; 5: 117–125.

Henneman L, Bramsen I, van der Ploeg HM et al: Participation in preconceptional carrier couple screening: characteristics, attitudes, and knowledge of both partners. J Med Genet 2001; 38: 695–703.

Wald NJ, Kennard A, Hackshaw A, McGuire A : Antenatal screening for Down's syndrome. J Med Screen 1997; 4: 181–246.

Al Mufti R, Hambley H, Farzaneh F, Nicolaides KH : Investigation of maternal blood enriched for fetal cells: role in screening and diagnosis of fetal trisomies. Am J Med Genet 1999; 85: 66–75.

Miny P, Tercanli S, Holzgreve W : Developments in laboratory techniques for prenatal diagnosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2002; 14: 161–168.

Brock DJ, Sutcliffe RG : Alpha-fetoprotein in the antenatal diagnosis of anencephaly and spina bifida. Lancet 1972; 2: 197–199.

Cuckle HS, van Lith JM : Appropriate biochemical parameters in first-trimester screening for Down syndrome. Prenat Diagn 1999; 19: 505–512.

Cole LA, Shahabi S, Oz UA et al: Urinary screening tests for fetal Down syndrome: II Hyperglycosylated hCG. Prenat Diagn 1999; 19: 351–359.

Marteau T : Towards informed decisions about prenatal testing: a review. Prenat Diagn 1995; 15: 12515–12526.

Nippert I, Horst J, Schmidtke J : Genetic services in Germany. Eur J Hum Genet 1997; 5 (Suppl 2): 81–88.

Bassett M, Dunn C, Battese K, Peek M : Acceptance of neonatal genetic screening for hereditary hemochromatosis by informed parents. Genet Test 2001; 5: 317–320.

Snijders RJ, Johnson S, Sebire NJ, Noble PL, Nicolaides KH : First-trimester ultrasound screening for chromosomal defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1996; 7: 216–226.

Wald N, Kennard A : Routine ultrasound scanning for congenital abnormalities. Ann NY Acad Sci 1998; 847: 173–180.

Levi S : Routine ultrasound screening of congenital anomalies. An overview of the European experience. Ann NY Acad Sci 1998; 847: 86–98.

Snijders RJ, Noble P, Sebire N, Souka A, Nicolaides KH : UK multicentre project on assessment of risk of trisomy 21 by maternal age and fetal nuchal-translucency thickness at 10–14 weeks of gestation. Fetal Medicine Foundation First Trimester Screening Group. Lancet 1998; 352: 343–346.

Pajkrt E, van Lith JM, Mol BW, Bleker OP, Bilardo CM : Screening for Down's syndrome by fetal nuchal translucency measurement in a general obstetric population. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1998; 12: 163–169.

Schwarzler P, Carvalho JS, Senat MV, Masroor T, Campbell S, Ville Y : Screening for fetal aneuploidies and fetal cardiac abnormalities by nuchal translucency thickness measurement at 10–14 weeks of gestation as part of routine antenatal care in an unselected population. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999; 106: 1029–1034.

Devine PC, Malone FD : First trimester screening for structural fetal abnormalities: nuchal translucency sonography. Semin Perinatol 1999; 23: 382–392.

Snijders RJ, Thom EA, Zachary JM et al: First-trimester trisomy screening: nuchal translucency measurement training and quality assurance to correct and unify technique. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002; 19: 353–359.

McFadyen A, Gledhill J, Whitlow B, Economides D : First trimester ultrasound screening carries ethical and psychological implications. BMJ 1998; 317: 694–695.

Brambati B : Prenatal diagnosis of genetic diseases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2000; 90: 165–169.

Handyside AH, Kontogianni EH, Hardy K, Winston RM : Pregnancies from biopsied human preimplantation embryos sexed by Y-specific DNA amplification. Nature 1990; 344: 768–770.

Geraedts J, Handyside A, Harper J et al: European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis Consortium Steering Committee, ESHRE preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) consortium: data collection II (May 2000). Hum Reprod 2000; 15: 2673–2683.

Harper JC, Wells D : Recent advances and future developments in PGD. Prenat Diagn 1999; 19: 1193–1199.

Pembrey ME : In the light of preimplantation genetic diagnosis: some ethical issues in medical genetics revisited. Eur J Hum Genet 1998; 6: 4–11.

The Ethics Committee of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine: Sex selection and preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Fertil Steril 1999; 72: 595–598.

Levi HL, Albers S : Genetic screening of newborns. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2000; 1: 139–177.

Motulsky A : Screening for Genetic Diseases. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 1314–1316.

Therrell Jr BL : US newnorn screening policy dilemmas for the twenty-first century. Mol Genet Metab 2001; 74: 64–74.

Cao A, Galanello R, Rosatelli MC : Prenatal diagnosis and screening of the haemoglobinopathies. Bailliere's Clin Haematol 1998; 11: 215–238.

Jaffe A, Bush A : Cystic fibrosis: review of the decade. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2001; 56: 240–247.

Shulman LP, Sherman E : Cystic fibrosis. Metab Genet screen 2001; 28: 383–393.

Dodge JA : Neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis. Cystic fibrosis should be added to diseases sought in all newborn babies. BMJ 1998; 317: 411.

Murray J, Cuckle H, Taylor G, Littlewood J, Hewison J : Screening for cystic fibrosis. Health Technol Assess 1999; 3: 1–104.

Nippert I, Clausen H, Frets P, Niermeijer MF, Modell M : Evaluating cystic fibrosis carrier screening development in Northern Europe: Denmark, the Federal Republic of Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Münster: Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität; 1998, vol. 2, no. 1, p114.

Wald NJ, Morris JK : Neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis. BMJ 1998; 316: 404–405.

Wildhagen MF, ten Kate LP, Habbema JD : Screening for cystic fibrosis and its evaluation. Br Med Bull 1998; 54: 857–875.

Wildhagen MF, Hilderink HB, Verzijl JG et al: Costs, effects, and savings of screening for cystic fibrosis gene carriers. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998; 52: 459–467.

Young SS, Kharrazi M, Pearl M, Cunningham G : Cystic fibrosis screening in newborns: results from existing programs. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2001; 7: 427–433.

Mischler EH, Wilfond BS, Fost N et al: Cystic fibrosis newborn screening: impact on reproductive behavior and implications for genetic counseling. Pediatrics 1998; 102: 44–52.

NIH: Consensus Development Conference Statement on Genetic Testing for Cystic Fibrosis. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 1529–1539.

Maheshwari M, Vijaya R, Kabra M et al: Prenatal diagnosis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Natl Med J India 2000; 13: 129–131.

Bradley DM, Parsons EP : Newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Semin Neonatol 1998; 3: 27–34.

Parsons EP, Clarke AJ, Hood K, Lycett E, Bradley DM : Newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a psychosocial study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2002; 86: F91–F95.

Parsons EP, Bradley DM : Complementary methodologies in the evaluation of newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. in Clarke AJ (ed): The genetic testing of children. Oxford: Bioscientific; 1998.

Wildhagen MF, van Os TA, Polder JJ, ten Kate LP, Habbema JD : Efficacy of cascade testing for fragile X syndrome. J Med Screen 1999; 6: 70–76.

Kallinen J, Heinonen S, Mannermaa A, Ryynanen M : Prenatal diagnosis of fragile X syndrome and the risk of expansion of a premutation. Clin Genet 2000; 58: 111–115.

Murray J, Cuckle H, Taylor G, Hewison J : Screening for fragile X syndrome: information needs for health planners. J Med Screen 1997; 4: 60–94.

Melis MA, Addis M, Lepiani C, Congeddu E, Cossu P, Cao A : A strategy for fragile-X carrier screening. Genet Test 1999; 3: 301–304.

Turner G, Robinson H, Wake S, Laing S, Partington M : Case finding for the fragile X syndrome and its consequences. BMJ 1997; 315: 1223–1226.

Ryynänen M, Heinonen S, Makkonen M, Kajanoja E, Mannermaa A, Pertti K : Feasibility and acceptance of screening for fragile X mutations in low-risk pregnancies. Eur J Hum Genet 1999; 7: 212–216.

The American College of Medical Genetics: Policy statement: Fragile X syndrome – diagnostic and carrier testing, 1994.

Humphries SE, Galton D, Nicholls P : Genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolaemia: practical and ethical issues. Q J Med 1997; 90: 169–181.

Kastelein JJ : Screening for familial hypercholesterolaemia. Effective, safe, treatments and DNA testing make screening attractive. BMJ 2000; 321: 1483–1484.

Marks D, Wonderling D, Thorogood M, Lambert H, Humphries SE, Neil HA : Screening for hypercholesterolaemia versus case finding for familial hypercholesterolaemia: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess 2000; 4: 1–123.

Nicholls P, Young I, Lyttle K, Graham C : Screening for familial hypercholesterolaemia. Early identification and tratment of patients is important. BMJ 2001; 322: 1062.

Wray R, Neil H, Rees J : Screening for hyperlipidaemia in childhood. Recommendations of the British Hyperlipidaemia Association. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1996; 30: 115–118.

Newman TB, Garber AM : Cholesterol screening in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2000; 105: 637–638.

Senior V, Marteau TM, Peters TJ : Will genetic testing for predisposition for disease result in fatalism? A qualitative study of parents responses to neonatal screening for familial hypercholesterolaemia. Soc Sci Med 1999; 48: 1857–1860.

Lashley FR : Genetic testing, screening, and counseling issues in cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs 1999; 13: 110–126.

Defesche JC, Kastelein JJ : Molecular epidemiology of familial hypercholesterolaemia. Lancet 1998; 352: 1643–1644.

Marang-van de Mheen PJ, van Maarle MC, Stouthard ME : Getting insurance after genetic screening on familial hypercholesterolaemia: the need to educate both insurers and the public to increase adherence to national guidelines in The Netherlands. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002; 56: 145–147.

Niederau C, Strohmeyer G : Srategies for early diagnosis of haemochromatosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 14: 217–221.

Feder JN, Gnirke A, Thomas W et al: A novel MHC class I-like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis. Nat Genet 1996; 13: 399–408.

Byrnes V, Ryan E, Barrett S, Kenny P, Mayne P, Crowe J : Genetic hemochromatosis, a Celtic disease: is it now time for population screening? Genet Test 2001; 5: 127–130.

Tavill AS : Cinical implications of the hemochromatosis gene. N Eng J Med 1999; 341: 755–757.

Power TE, Adams PC : Psychosocial impact of C282Y mutation testing for hemochromatosis. Genet Test 2001; 5: 107–110.

Bassett ML, Leggett BA, Halliday JW, Webb S, Powell LW : Analysis of the cost of population screening for haemochromatosis using biochemical and genetic markers. J Hepatol 1997; 27: 517–524.

Vautier G, Murray M, Olynyk JK : Hereditary haemochromatosis: detection and management. Med J Aust 2001; 175: 418–421.

Burke W, Franks Al, Bradley LA : Screening for hereditary hemochromatosis: are DNA-based tests the answer? Mol Med Today 1999; 5: 428–430.

The European and UK Haemochromatosis Consortia: Diagnosis and management of haemochromatosis since the discovery of the HFE gene: a European experience. Br J Haematol 2000; 108: 31–39.

Bradley LA, Haddow JE, Palomaki GE : Population screening for haemochromatosis: a unifying analysis of published intervention trials. J Med Screen 1996; 3: 178–184.

Burke W, Thomson E, Khoury MJ et al: Hereditary hemochromatosis: gene discovery and its implications for population-based screening. JAMA 1998; 280: 172–178.

Beutler E, Felitti YJ : The C282Y mutation does not shorten life span. Arch Intern Med 2002; 27: 1196–1197.

Haddow JE, Bradley LA : Hereditary haemochromatosis: to screen or not. BMJ 1999; 319: 531–532.

McCullen MA, Crawford DH, Hickman PE : Screening for hemochromatosis. Clin Chim Acta 2002; 315: 169–186.

ANAES (National Agency for Accreditation and Evaluation in Health): Evaluation clinique et économique: intérêt du dépistage de l'hémochromatose génétique en France. Paris: ANDEM; 1999.

Stuhrmann M, Notker G, Thilo D, Schmidtke J : Mutation screening for prenatal and presymptomatic diagnosis: cystic fibrosis and haemochromatosis. Eur J Pediatr 2000; 159 (Suppl 3): S186–S191.

Witte DL, Crosby WH, Edwards CQ, Fairbanks VF, Mitros FA : Practice guideline development task force of the College of American Pathologists. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Clin Chim Acta 1996; 245: 139–200.

Myles J, Duffy S, Nixon R et al: Initial results of a study into the effectiveness of breast cancer screening in a population identified to be at high risk. Rev Epidemiol Sante publ 2001; 49: 471–475.

Young SR, Brooks KA, Edwards JG, Smith ST : Basic principles of cancer genetics. J SC Med Assoc 1998; 94: 299–305.

Aktan-Collan K, Mecklin JP, de la Chapelle A, Peltomaki P, Uutela A, Kaariainen H : Evaluation of a counselling protocol for predictive genetic testing for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. J Med Genet 2000; 37: 108–113.

Lenoir GM : Genetic predisposition to cancer development. Rev Prat 1995; 45: 1889–1894.

Aktan-Collan K, Mecklin JP, Jarvinen H et al: Predictive genetic testing for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer: uptake and long-term satisfaction. Int J Cancer 2000; 89: 44–50.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology: Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility, Adopted on February 20, 1996. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14: 1730–1736, discussion 1737–1740.

Eisinger F, Alby N, Bremond A et al: Recommendations for medical management of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: the French National Ad Hoc Committee. Ann Oncol 1998; 9: 939–950.

Burke W, Petersen G, Lynch P et al: Recommendations for follow-up care of individuals with an inherited predisposition to cancer. I. Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Cancer Genetics Studies Consortium. JAMA 1997; 277: 915–919.

Burke W, Daly M, Garber J et al: Recommendations for follow-up care of individuals with an inherited predisposition to cancer. II. BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cancer Genetics Studies Consortium. JAMA 1997; 277: 997–1003.

Eisinger F, Burke W, Sobol H : Management of women at high genetic risk of ovarian cancer. Lancet 1999; 354: 1648.

Burke W, Coughlin SS, Lee NC, Weed DL, Khoury MJ : Application of population screening principles to genetic screening for adult-onset conditions. Genet Test 2001; 5: 201–211.

Kronborg O : Screening for early colorectal cancer. World J Surg 2000; 24: 1069–1074.

Li FP : Cancer control in susceptible groups: opportunities and challenges. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 719–725.

Hodgson S, Milner B, Brown I et al: Cancer genetics services in Europe. Dis Markers 1999; 15: 3–13.

Lane B, Challen K, Harris HJ, Harris R : Existence and quality of written antenatal screening policies in the United Kingdom: postal survey. BMJ 322, 2001; 22–23.

Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Bradley LA : Doherty RA: Screening for cystic fibrosis. JAMA 1998; 279: 1068–1069.

Modell B, Harris R, Lane B et al: Informed choice in genetic screening for thalassaemia during pregnancy: audit from a national confidential inquiry. BMJ 2000; 320: 337–341.

Cao A, Rosatelli MC, Galanello R : Control of beta-thalassaemia by carrier screening, genetic counselling and prenatal diagnosis: the Sardinian experience. Ciba Found Symp 1996; 197: 137–155.

Modell M, Wonke B, Anionwu E et al: A multidisciplinary approach for improving services in primary care: randomised controlled trial of screening for haemoglobin disorders. BMJ 1998; 317: 788–791.

Rowley PT, Loader S, Levenkron JC : Cystic fibrosis carrier population screening: a review. Genet Test 1997; 1: 53–59.

Cuckle HS : Extending antenatal screening in the UK to include common monogenic disorders. Community Genet 2001; 4: 84–86.

Henneman L, ten Kate LP : Preconceptional couple screening for cystic fibrosis carrier status: couples prefer full disclosure of test results. J Med Genet 2002; 39: E26.

Chadwick R, Ten Have H, Husted J et al: Genetic screening and ethics: European perspectives. J Med Philos 1998; 23: 255–273.

McGleenan T : Genetic testing and screening: the developing European jurisprudence. Human reproduction and genetic ethics 1999; 5: 11–19.

Aghababian V, Auquier P, Hairiou D et al: Diagnostic génétique prénatal: comparaison des législations en Europe. J Med Légale Droit Méd 1997; 40: 441–449.

Danish Council of Ethics: Ethics and Mapping of the Human Genome. Copenhagen: Danish Council of Ethics; 1993.

The German Society of Human Genetics: Statement on heterozygote screening, 1991.

The Health Council of the Netherlands: Committee Genetic Screening, Genetic Screening, The Hague, 1994.

Nuffield Council on Bioethics: Genetic Screening Ethical Issues, 1993.

WHO: WHO, Guidelines on ethical issues in medical genetics and the provision of genetic services. Geneva: WHO; 1995.

WHO: WHO Technical report series, control of hereditary diseases. Geneva: WHO; 1996.

WHO: WHO Human genetics programme, proposed international guidelines on ethical issues in medical genetics and genetic services. Geneva: WHO; 1997.

The Royal College of Physicians of London: Purchasers' Guidelines to Genetics Services in the NHS. London: The Royal College of Physicians of London; 1991.

Krawczak M, Cooper DN, Schmidtke J : Estimating the efficacy and efficiency of cascade genetic screening. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 69: 361–370.

Holloway S, Brock DJ : Cascade testing for the identification of carriers of cystic fibrosis. Med Screen 1994; 1: 159–164.

Brock DJ : Population screening for cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pediatr 1996; 8: 635–638.

Modell B : Delivering genetic screening to the community. Ann Med 1997; 29: 591–599.

Bennett R : Antenatal genetic testing and the right to remain in ignorance. Theor Med Bioethics 2001; 22: 461–471.

Freda MC, DeVore N, Valentine-Adams N, Bombard A, Merkatz IR : Informed consent for maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening in an inner city population: how informed is it? Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 1998; 27: 99–106.

Denayer L, Welkenhuysen M, Evers-Kiebooms G, Cassiman JJ, Van den Berghe H : Risk perception after CF carrier testing and impact of the test result on reproductive decision making. Am J Med Genet 1997; 69: 422–428.

Mennie ME, Axworthy D, Liston WA, Brock DJ : Prenatal screening for cystic fibrosis carriers: does the method of testing affect the longer-term understanding and reproductive behaviour of women? Prenat Diagn 1997; 17: 853–860.

Macklin R : Understanding informed consent. Acta Oncol 1999; 38: 83–87.

Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ, Thornton J, Hewison J : Informed consent for clinical trials: in search of the ‘best’ method. Soc Sci Med 1998; 47: 1825–1840.

ASHG: ASHG statement. Professional disclosure of familial genetic information. The American Society of Human Genetics Social Issues Subcommittee on Familial Disclosure. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 474–483.

Smith K : Genetic testing of the general population: ethical and informatic concerns. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 2000; 28: 557–561.

Elias S, Annas GJ : Generic consent for genetic screening. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 1611–1613.

Caulfield T : The commercialization of human genetics: profits and problems. Mol Med Today 1998; 4: 148–150.

Holtzman NA, Watson MS : Promoting safe and effective genetic testing in the United States. Final Report of the Task Force on Genetic testing. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1997.

Cho MK, Sankar P, Wolpe PR, Godmilow L : Commercialization of BRCA1/2 testing: practitioner awareness and use of a new genetic test. Am J Med Genet 1999; 83: 157–163.

Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Petersen GM et al: The use and interpretation of commercial APC gene testing for familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 823–827.

Cuckle HS, Lilford R, Wilson J, Sehmi I : Direct marketing of cystic fibrosis carrier screening: commercial push or population need? J Med Genet 1995; 33: 758.

Kaufert PA : Health policy and the new genetics. Soc Sci Med 2000; 51: 821–829.

Chadwick R, Ten Have H, Hoedemaekers R et al: Euroscreeen 2: towards community policy on insurance, commercialization and public awareness. J Med Philos 2001; 26: 263–272.

Caulfield T : The commercialization of human genetics in canada: an overview of policy and legal issues. in Knoppers BM (ed): Socio-ethical issues in human genetics. Montreal: Les Editions Yvon Blais Inc.; 1998, pp 343–402.

Dequeker E, Cassiman JJ : Evaluation of CFTR gene mutation testing methods in 136 diagnostic laboratories: report of a large European external quality assessment. Eur J Hum Genet 1998; 6: 165–175.

The Advisory Committee on Genetic Testing: New guidelines for postal genetic testing. Genethics News 1997; 15: 3.

King D : Genetic testing by post: how should it be controlled. Genethics News 1997; 15: 7.

Hoedemaekers R : Commercialisation – topics for reflection. Euroscreen newsletter, issue 10, Autumn: 1998.

The Report of the French National Consultative Ethics Committee: Opinions and Recommendations on Genetics and Medicine: from Prediction to Prevention, Reports, Paris, 1995, in French National Consultative Ethics Committee for Health and Life Sciences, Opinions, Recommendations, Reports 1984–1997, Levallois-Perret, Biomédition, 1998.

Terrenoire G : Le rôle des associations. in Comité consultatif national d'éthique pour les sciences de la vie et de la santé (dir.) Génétique et médecine, de la prédiction à la prévention. Paris: Documentation française; 1997, pp 135–137.

Green A : Neonatal screening: current trends and quality control in the United Kingdom. Rinsho Byori 1998; 46: 211–216.

Simonsen H, Brandt NJ, Norgaard-Pedersen B : Neonatal screening in Denmark. Status and future perspective. Ugeskr Laeger 1998; 28: 5777–5782.

Jorgensen FS, Valentin L, Salvesen KA et al: MULTISCAN – a Scandinavian multicenter second trimester obstetric ultrasound and serum screening study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999; 78: 501–510.

Wald NJ, Watt HC, Hackshaw AK : Integrated screening for Down's syndrome on the basis of tests performed during the first and second trimesters. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 461–467.

Girodon Boulandet E, Cazeneuve C, Goossens M : Screening practices for mutations in the CFTR gene ABCC7. Hum Mutat 2000; 15: 135–149.

Elles R : An overview of clinical molecular genetics. Mol Biotechnol 1997; 2: 95–104.

Peckham CS, Dezateux C : Issues underlying the evaluation of screening programmes. Br Med Bull 1998; 54: 767–778.

Robson J : Screening in general practice and primary care. Br Med Bull 1998; 4: 961–982.

Stewart S, Stone D : Screening in Scotland. Health Bull (Edinb) 1996; 54: 13–15.

Stoddard JJ, Farrell PM : State-to-state variations in newborn screening policies. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997; 151: 561–564.

Sherriff R, Best L, Roderick P : Population screening in the NHS: a systematic pathway from evidence to policy formulation. J Public Health Med 1998; 20: 58–62.

Dezateux C : Evaluating newborn screening programmes based on dried blood spots: future challenges. Br Med Bull 1998; 54: 877–890.

Romano PS, Waitzman NJ : Can decision analysis help us decide whether ultrasound screening for fetal anomalies is worth it? Ann NY Acad Sci 1998; 847: 154–172.

Parsons EP, Bradley DM, Clarke AJ : Disclosure of Duchenne muscular dystrophy after newborn screening. Arch Dis Child 1996; 74: 550–553.

Uttermann G : Genetic services in Austria. Eur J Hum Genet 1997; 5 (Suppl 2): 31–34.

von Koskull H, Salonen R : Genetic services in Finland. Eur J Hum Genet 1997; 5 (Suppl 2): 69–75.

Schroeder-Kurth T : Screening in Germany: carrier screening, prenatal care and other screening projects. in Chadwick R, Shickle D, Ten Have H, Wiesing U (eds): The ethics of genetic screening. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999, pp 81–87.

Bartsocas CS : Genetic services in Greece. Eur J Hum Genet 1997; 5 (Suppl 2): 89–92.

Ferrari M : Consistency in ethical reasoning concerning genetic testing and other health related practices in occupational and non-occupational settings, Brussels, European Commission, 1998-2001, (europa.eu.int/comm/research/biosociety/pdf/bmh4_ct98_3479_partb.p).

Ministry of Health and Social Affairs: Biotechnology related to human beings. Report no. 25 to the Storting Norway: Oslo; 1993.

Tranebjaerg L, Borresen-Dale AL, Hansteen IL, Heim S, Kvittingen EA, Moller P : Genetic services in Norway. Eur J Hum Genet 1997; 5 (Suppl 2): 130–134.

Ramos-Fuentes F : Genetic testing in Spain. in Karlic H, Horak A (eds): Proceedings of the genetic testing in Europe: harmonisation of standards and regulations. Austria: Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Leukemia Research and Hematology, Hanusch Hospital & General Directorate VI, Federal Chancellery Austria; 1998, pp 26–30.

Kristofferrson U : Genetic services in Sweden. Eur J Hum Genet 1997; 5 (Suppl 2): 169–173.

Pescia G : Genetic services in Switzerland. Eur J Hum Genet 1997; 5 (Suppl 2): 174–177.

House of Commons Select Committee on Science and Technology: Human Genetics: the Science and Its Consequences. Third Report, HMSO: 1995.

Council of Europe: Recommendation on Prenatal Genetic Screening, Prenatal Gentic Diagnosis and Associated Genetic Counselling, 1990.

Council of Europe: Recommendation on genetic testing and screening for health-care purposes of the European Committee of Ministers, 1992.

Council of Europe: Recommendation on Screening as a Tool of Preventive Medicine of the European Committee of Ministers, 1994.

Council of Europe: Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine. April: 1997.

UNESCO: International bioethics Committee, Report of the Working Group on Genetic Screening and Testing, 1994.

UNESCO: The Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights. November: 1997.

HUGO: Statement on the Principled Conduct of Genetics Research, 1995.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A:

International and national regulatory frameworks

European Countries

Austria

The Gene Technology Act (Law BGB 510/1994), 1994: This law regulates the use of genetic testing and gene therapy in human beings. Part IV of the legislation addresses the issue of genetic screening; the legislation imposes conditions requiring the fully informed consent of the individual to be screened (Section 65). The consent requirements also apply to the use of prenatal genetic screening techniques. Section 64 stipulates that ‘DNA-based screening may be carried out but imposes a number of conditions so that screening may only be carried out where it is at the request of a doctor specialising in medical genetics or a doctor for the respective speciality and either for verification of a predisposition to a late onset disorder or for verification of carrier status or the diagnosis of an existing disease or late onset disorder. DNA-based screening may also be carried out as part of preparation for gene therapy and the monitoring of the effectiveness of any gene therapy treatment’.112

According to the Act, premises, where genetic tests for the diagnosis of a predisposition or for the identification of a carrier status of inherited diseases are performed, have to be approved by the Ministry of Health and Consumer Protection. For the authorization of premises for the performance of predictive genetic testing on humans, certain requirements have to be fulfilled. These requirements pertain to the structural and apparative condition of the premises, an adequate qualification and experience of the performing staff and sufficient measures for quality assurance, in order to ensure that genetic tests are carried out according to the state of the art and that the data gained from these tests are strictly protected. Genetic counselling has to be carried out before and after genetic testing, and has to include psychological or social aspects. If all these requirements are met, the premises will be approved by the competent authority on the basis of the opinion given by the relevant scientific committee of the gene technology commission.163

Belgium

Although there is little specific legislation relating to genetics a Higher Council on Human Genetics was established in 1973. In 1987, a Crown Order established standards which must be met by any centre operating in the field of human genetics. In 1992, the Belgian parliament enacted the Law on Insurance Contracts that precluded insurance companies from using genetic testing in the determination of life or health insurance contract. The same law prohibits a candidate to communicate genetic information to the insurer, thus indirectly prohibiting the latter to request such information.

Denmark

-

Danish Council of Ethics, Protection of Sensitive Personal Information – A Report, Copenhagen, 1992

-

Danish Council of Ethics, Ethics and Mapping of the Human Genome, Copenhagen, 1993: See the section on ‘The Danish Council of Ethics, ethics and mapping of the human genome’.

-

Danish Council of Ethics, Genetic Screening – A Report, Copenhagen, 1993: This report recommended that all genetic screening projects should be ethically evaluated by the Central Scientific Committee (which approve all medical research involving human beings) as well as by the Council of Ethics itself. The report also stated principles for the information of persons to be tested, and for the evaluation of the consequences of genetic screening.

-

Danish Centre for Human Rights, Genetic Test, Screening and Use of Genetic Data by Public Authorities in Criminal Justice, Social Security and Alien and Foreigners Acts, Copenhagen, 1993

-

Danish National Board of Health, Guidelines and recommendations for indications for prenatal diagnosis, 1994

-

Danish Council of Ethics, Priority-setting in the Health Services, 1997: Genetic screening is mainly regulated through the legal regulations that in general applies to the Danish health care system.

Finland

In 1997, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health set up a Working Party to evaluate genetic screening programmes and the ethical and social issues involved with it. The Working Party gave its report in 1998: the main conclusion was that genetic screening programmes should always be approved by an official health care authority; the details of this should be legislated. There should be a national board of experts who should follow the research and practices concerning genetic screening.

There is no specific regulations of genetic testing in laboratories. The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health supervises genetic testing as part of supervision and quality control of both the public sector and the private laboratories. Recommendations on quality control have been published and updated several times by the Society for Medical Genetics.164

-

Primary Health Care Act and Decree, 1971: This Act regulates the duties of municipalities regarding screenings. For the patients all screenings are voluntary.

-

Act on the Status and Rights of patients, 785/1992: The act regulates, that is, patient's right to be informed about his/her state of health, patient's right to self-determination, drafting and keeping patient documents and confidentiality of information in patient documents.

-

Gene Technology Act, 1995: This act aims to promote the safe use and development of gene technology.

-

The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Report of a Working Party on Genetic Screening, 1998.

France

-

Laws No. 94-653 of 29 July 1994 on respect for the human body: This law modifies the Civil Code by introducing notably the notions of the fundamental right to respect for one's body, therapeutic necessity as the only acceptable reason for violating bodily integrity and this only if the individual has consented. A genetic test can only be carried out for medical or scientific purposes, and only after consent has been obtained from the individual. Strict penalties are provided if case abuse occurs.

-

Laws No. 94-654 of 29 July 1994 on the donation and use of elements and products of the human body, medically assisted procreation and prenatal diagnosis: Prenatal diagnosis is defined as including medical techniques aimed at detecting in utero a particularly severe disorder but not necessarily incurable. It must be preceded by a medical genetic counselling consultation. The cytogenetic and biological analyses must be carried out in authorized establishments. Preimplantation diagnosis is only allowed in certain circumstances: a physician working in a pluridisciplinary prenatal diagnosis center must attest that a couple runs a high risk of having a child suffering from a particularly severe genetic disease that is incurable at the time of diagnosis; the genetic anomaly must have been identified in one of the parents; both members of the couple must give written consent to the test. The purpose of the test is limited to finding the affection, and looking for ways to prevent and treat it.

-

National Ethical Consultative Committee for the Life and Health Sciences in France, Genetics and Medicine: From Prediction to Prevention, Paris, 1995: Genetic screening is the subject of this report, which in the absence of a specific law, declares the ethical principles that must be respected, with respect to all the activities involved in genetic screening. Its recommendations cover the following topics and ethical principles: respect of the autonomy of the subject, respect of medical confidentiality; respect of privacy in computerizing personal data; the use of biological samples; the prohibition of using results of genetic tests for purposes other than medical or scientific; procedures of accreditation of the materials involved in genetic testing; prior evaluation of the impact of the tests; information and formation of all medical personnel in genetics; the need to guarantee correct public information; prohibition of all uses that would contribute to stigmatization or unfair discrimination in the social and economic spheres.

-

National Advisory Committee on Bioethics and National College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians Guidelines, 1997: The topics covered by these guidelines are prenatal diagnosis, preimplantation diagnosis and predictive testing for late-onset diseases.

-

National Consultative Ethics Committee, Review of the Law No 94-653 of 29 July 1994: propositions regarding preimplantation diagnosis and prenatal diagnosis, 1998

-

Parliamentary Office for Evaluating Scientific and Technological Choices, Report on the application of the law of 29 July 1994 concerning the donation and use of elements of the human body, medically assisted procreation and prenatal diagnosis, 1999: This report will serve as the basis for the parliamentary discussion scheduled for the second semester of 2000.

Germany

The various States of the Republic of Germany have State Boards of Physicians who have to ratify the guidelines of the Federal Medical Association in order to put them in action. The States have no regulatory legislation on screening.

-

The German Bundestag, Chancen und Risken der Gentechnologie Enquete-Commission, 1987: Prenatal diagnosis and newborn screening programmes were accepted. The document recommended the creation of a number of new offences in the German Criminal Code including the creation of a new offence of manipulating the germ line of a human being, and recommended a new criminal offence where an employer discriminates against an employee on the basis of the results of his genetic test. The report also contained detailed recommendations on the consent and counselling requirements which must be fulfilled before any genetic screening can be carried out. In most instances, the report did not recommend that legislation be enacted but rather that these matters be supervised by authoritative professional bodies.112

-

The Embryo Protection Law of 1990: This law regulates medical actions around in vitro reproduction. It forbids by penalty to manipulate the embryos, to start more than three embryos, they are for implantation only. IVF is restricted to cases of infertility.

-

Bundesministerium für Forschung und Technologie, Die Erforschung des menschlichen Genoms. Ethische und soziale Aspekte, 1990: The Federal Ministry of Research and Technology established a working group in order to evaluate the Ethical and Social Aspects of the Human Genome Analysis. Population screening and its problems was evaluated, as well as the screening with versus without medical indication and the necessity of informed consent vs informed refusal.165

-

Berufsverband Medizinische Genetik, Stellungnahme zu einem möblichen Heterozygoten – Screening bei Cystischer fibrose, Medizinische Genetik, 1990: The German Medical Genetics Association published a Statement about Screening of Heterozygotes pointing to the danger of discrimination of carriers within an uneducated society.165

-

The German Society of Human Genetics,115 Statement on heterozygote screening, 1991: The German Society states that for population screening, the public must be fully and competently educated about the project and that there be guarantees that participation of the examinees is voluntary, that the examinees are able to comprehend the significance of their decision, that the individuals responsible for counselling and examination are qualified to do so, and that possible risks be evaluated beforehand. Therefore, the German Society rejects this type of population screening at present since the basic preconditions are not met. This applies to education of the public, the guarantee that the required counselling is qualified, and the carrying out of scientific projects on which future decisions can be based.

-

Bundesärztekammer, Memorandum, Genetisches Screening, Deutsches Ärzteblatt 89, 25126, 1992: The Scientific Council of the German Federal Board of Physicians Medical Association Memorandum dealt with population carrier screening. This influential Memorandum pointed to the missing goal of population screening of genetic defects for everybody when testing for average risks.165

-

The German Society of Human Genetics, Statement on genetic diagnosis in childhood and adolescence, 1995

-

The German Society of Human Genetics, Guidelines for molecular genetic diagnosis, 1996

-

The German Society of Human Genetics, Guidelines for genetic counselling, 1996

-

The German Society of Human Genetics, Position Paper, 1996: This paper defines standards for the application of genetic tests to nearly all fields of practical genetics: heterozygosity testing and screening, genetic testing in children, prenatal diagnosis, predictive testing.

-

The Professional Association of Medical Genetics, Principles of genetic counselling, 1996

-

Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesârztekammer, Richtlinien zur pränatalen Diagnostik von Krankheiten und Krankheitsdispositionen, Deutsches Arzteblatt 95, C-2284-3242, 1998: These guidelines for prenatal diagnosis of disorders and dispositions for diseases describes the indications for any invasive interventions, goals and conditions like counselling before and after the test. Maternal serum screening has been emphasized as an appropriate and valid methodology.

-

Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesârztekammer, Richtlinien zur Diagnostik der genetischen Dispositionen für Krebserkrankungen, Deutsches Arzteblatt 95, B-1120-1127, 1998: These guidelines for diagnosing genetic dispositions for cancer state that diagnoses for patients suffering from cancer are differentiated from screening for dispositions in healthy persons who have some indications for this test and who need to be counselled before and after the test. Otherwise, any patient in ambulances or clinics has a right to get diagnosed and to learn about the nature of his disease.

In Germany, there is a special committee that, all 1–3 years, publishes consensus resolutions and guidelines as to maternal serum screening: Northelmer Konsensus-Tagungen.

-

Rauskolb R, Blutuntersuchungen bei Schwangeren zur pränatalen Erkennung von Chromosomenanomallen und Neuralrohrdefekten (sog. Triple-Test), Der Frauenarzt 1993; 34 : 254–258.

-

Braulke I, Rauskolb R, Blutuntersuchungen bei Schwangeren zur pränatalen Diagnostik von Chromosomenanomallen und Neuralrohrdefekten (sog. Triple-Test), Bericht ber die 2, Konsenstagung, Der Frauenarzt 1995; 36 : 98–99.

-

Braulke I, Rauskolb R, Blutuntersuchungen bei Schwangeren zur pränatalen Risikopräzislerung für Chromosomenanomallen und Neuralrohrdefekten (sog. Triple-Test), Med Genet 1996; 4 : 348–352.

-

Pauer HU, Rauskolb R, Blutuntersuchungen bei Schwangeren zur pränatalen Risikopräzislerung für Chromosomenanomallen und Neuralrohrdefekten (sog. Triple-Test), Der Frauenarzt, 1999; 40 : 518–522.

-

The fifth Consensus Conference, First trimester screening in Germany, 1999

-

Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesârztekammer, Richtlinien zur Durchfuehrung der assistierten Reproduktion, Deutsches Arzteblatt 95, C-2230-2235, 1998: In this professional guidelines for IVF, no other indications than those authorized by the Embryo Protection Law are accepted. Preimplantation diagnosis is not allowed.

Attempts are being made by some institutions today to review and discuss the technical possibilities of PGD, the question of its necessity, and the ethical, social and legal problems, in particular the necessary changes of the Embryo Protection Law and the professional guidelines for IVF. In addition, the reformed Abortion Law of 1995 still bans abortion but allows exceptions under certain conditions. The jurisdiction in the German constitution protects the diseased or disabled. Therefore a future disorder or disability of the foetus can not be used as sole reason for abortion. These principles cause difficulties in discussions pro PGD.

Greece

In 1977, Greek legislation changed the abortion law to allow termination of the pregnancy up to the 24th week for medical reasons. There is no legislation concerning practice in genetics. Currently, a five-member Bioethics Committee, reporting directly to the Prime Minister is preparing guidelines regarding the ethical and social issues of genetic testing. Since 1981, the Hellenic Association of Medical Genetics has been trying to get approval from the government concerning a national genetics programme that would include all the existing units and establish new units of genetics all over the country under specific structure and organization. Quality control systems are not existent and the Hellenic Association of Medical Genetics has not been involved up until today in the organisation of such a system.166

Iceland

Iceland has no law that specifically deals with human genetics. There is a law (no. 18/1996) on genetically engineered organisms. The law on patients' rights (no. 74/1997) has some relevance here, as do laws on health-care service (97/1990), on personal privacy and data protection (121/1989), and some other laws (eg 53/1988, 37/1993, 50/1996).

-

Act no. 121/1989 on Personal Privacy and Data Protection, Ministry of Health, 1989: The implementation of the Data Protection Act is monitored by the Data Protection commission, a special independent official agency, appointed by the Minister of Justice for a period of 4 years. The commission has an important role both as a standard setting and a monitoring body.

-

Act no. 97/1990 on a Healthcare Services, Ministry of Health, 1990.

-

Act no. 74/1997 on the Rights of Patients, Ministry of Health, 1997: This Act includes fundamental rights of patients including rules on consent, confidentiality and handling of information in clinical records.

-

Act no. 139/1998 on a Health Sector Database, Ministry of Health, 1998: This Act is in compliance with the Act on the Rights of Patients. By reference to article 29 in the Act on the Rights of Patients, the Minister of Health and Social Security has issued a regulation on scientific research in the health sector (Reg. No. 552/1999) where a special Scientific Ethics Committee is founded. The Committee is given a specific role in the Act on HSD.

Ireland

There are no specific regulations or laws in place regarding genetic testing. Similarly, no specific schemes are in place for the licensing or accreditation of laboratories involved in genetic testing.

Italy

-

Legge No 104/5 febbraio 1992 (Gazzetta Ufficiale), Legge-quadro per l'assistenza, l'integrazione sociale e i diritti delle persone handicappate

-

The Italian Committee on Bioethics, Prenatal Diagnosis, 17 July 1992

-

Legge No 548/23 dicembre 1993 (Gazzetta Ufficiale), Disposizioni per la prevenzione e la cura della fibrosi cistica

-

The Italian Committee on Bioethics, Identity and Rights of the Embryo, 22 June 1996

-

The Italian Committee on Bioethics, Human Genome Project, 18 March 1994 and 21 February 1997

-

National Guidelines for Genetic Testing, 1998: In May 1998, the Italian Government has approved the National Guidelines for Genetic Testing prepared by a Task Force. The general objectives are: (1) ensuring the safety and effectiveness of both existing and newly introduced genetic tests; (2) defining the criteria for quality assurance of laboratories performing genetic tests; (3) ensuring both adequate counselling and the free decision of individuals and families; this will include a particular attention to problems concerning ethics and privacy. Some topics deserving a specific concern have been identified, namely: genetic testing for prenatal diagnosis, genetic testing for susceptibility to cancer, and genetic testing for rare diseases.167

-

Decreti presidenziali, 9 luglio 1999 (Gazzetta Ufficiale), Accertamenti per la diagnosi delle malformazioni (Art. 1): This decree address the screening of the following diseases: CF, phenylketonuria and congenital hypothyroidism. It establish that these services must be free of charge.

-

Law no. 675, 31 December 1996, D.P.R. no. 318, 28 July 1999, on Medical Information Privacy

-

The Italian Committee on Bioethics, Orientamenti bioetici per i test genetici, 19 November 1999: Genetic information must be treated as the general medical information and therefore it is forbidden to give this information to insurers or employers without consent.

Norway

-

Ministry of Health and Social Affairs,168 Biotechnology Related to Human Beings, Report No. 25 to the Storting, Oslo, 1992–1993: Screening shall only take place if it offers clear therapeutic benefits for the individual.

-

Act Relating to the Application of Biotechnology in Medicine, Law no. 56 of 5 August 1994: This Act gives a frame of general guidelines for assisted reproductive technology applications, research on embryos, preimplantation diagnosis, prenatal diagnosis, genetic testing after birth and gene therapy. This Act also specifies obligations about authorization of institutions applying medical biotechnology and the duty for such institutions to report regularly on their activities to the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs.169

Genetic testing for diagnostic purposes is permitted without restrictions, but the law requires that comprehensive genetic counselling be given before, during and after genetic tests performed on healthy persons for presymptomatic, predictive or carrier purposes. Presymptomatic, predictive and carrier testing is limited to individuals above the age of 16 years. When the information refers to a diagnostic test, genetic results may be communicated, without restrictions, between medical institutions authorized to apply medical biotechnology. However, the exchange of genetic information about presymptomatic, predictive or carrier tests is restricted. The Act states that it is prohibited to ask whether a presymptomatic, predictive or carrier test has been performed. Gene therapy is only allowed as somatic cell therapy and individuals below the age of 16 years need the consent of their parents or guardians.169

Portugal

The Ratification of the ‘Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being and the additional protocol on the prohibition of cloning human beings' was published in January 2001. Since 1995, the Ministry of Health has named a task force in order to prepare guidelines for medical genetics and prenatal diagnosis.

-

Act No. 10/95 related to the Protection of Personal Information

-

Despacho Ministerial No. 9108/97, Guidelines for Molecular Genetic Diagnosis

-

Circular normativa No. 6/DSMIA/DGS, 1997, Recommendations for Maternal Serum screening Programs

-

Despachos Ministerials No. 5411/97 e No 10325/99, Principles and Practice for prenatal diagnosis

-

Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being and the additional protocol on the prohibition of cloning human beings, 2001

Spain

There is no specific legislation to ensure the appropriateness of genetic procedures and the confidentiality of personal data. Consent to undergo to any medical tests is granted through General Health Law of 25 April 1986; article 10.6 states the right of a patient to choose freely between options given by the physician in charge of his case. Protection of data related to health may be reached through general rules concerning personal data protection, as well as through provisions which recognise the duty of confidentiality in the health field. The Organic Law regulating the automated processing and protection of personal data of 13 December 1999 provides special measures of protection for personal health data. Among other fundamental rights, the general legal principle of non discrimination is stated by the Spanish Constitution of 1978, which forbids any kind of discrimination on grounds of any personal condition.170

Quality assessment schemes for genetic services have been addressed in specific areas. In 1996, standard criteria for quality control of cytogenetic and prenatal diagnosis laboratories were issued, and currently there are plans to develop quality standards for clinical and molecular genetic services.170

In September 1999, Spain subscribed and joined the European Agreement for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine.

-

The Spanish Constitution of 1978

-

Protocolos de Procedimientos Diagnosticos y Terapeuticos. Obstetricia. Medicina Materno Infantil (SEGO), Madrid 1985

-

General Health Law of 25 April 1986

-

The Royal Decree of 21 November of 1986: This Decree rules out the conditions for the Centers to be authorized to perform therapeutic abortion, preimplantation and prenatal tests, as well the requisites to be filled in by practitioners concerned.

-

The Act 35/1988 of 22 November on Techniques of Assisted Reproduction, 1988: This law regulates the human reproduction techniques when they are performed by a specialist in authorized public or private medical centers. Article 12 regulates preimplantation and prenatal diagnosis. Articles 14–17 permit investigation and experimentation for the treatment and prevention of genetic disorders under determined conditions. Article 159 permits that manipulation of human genes only when the intention is the elimination or the improvement of a serious illness.

-

Ministry of Health, Handbook for Prenatal Diagnosis, Madrid, 1989

-

The Organic Law regulating the automated processing of personal data of 29 October 1992

-

Recomendaciones y Protocolos en Diagnostico Prenatal. Report of the European Study Group on Prenatal Diagnosis, 1993

-

Guidelines for prenatal cytogenetics, 1996

-

The Organic Law regulating the automated processing and protection of personal data of 13 December 1999

-

Catalan agency for health technology assessment and research, Prenatal screening of cystic fibrosis, 2000: The proposes were: According to the available scientific evidence on the efficacy and effectiveness of prenatal screening of CF, the implementation of a systematic, general screening programme for CF in all newborns in Catalonia is not recommended. Coordinated international studies, presenting new scientific evidence on the effectiveness of the early diagnosis and treatment of CF are required – it is unlikely that the Catalan data alone would provide with a conclusive answer to this issue.

Sweden

-

National Board of Health and Social Welfare, Neonatal screening for metabolic diseases, SOSFS, 1988

-

Law 114 of March 1991 on the Use of Certain Gene Technologies within the Context of General Medical Examinations (1993): This law examines the use of certain genetic technology in medical screening. There must be a permission from the National Board of Health and Welfare. Authorization from this body is required before DNA testing can be carried out. This requirement extends to the use of genetic screening techniques for diagnostic purposes.

-

Swedish Society for Medical Genetics, 1994: The Swedish Society for Medical Genetics has brought forward a quality assessment document for clinical genetic units including guidelines for cytogenetic and molecular routines as well as for genetic counselling. This document has been adopted by all the university clinical genetic departments as a minimum standard for quality.171

-

The Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Guidelines on the use of prenatal diagnosis and preimplantation diagnosis, 1995: These guidelines regulate prenatal diagnoses and include prenatal diagnosis by genetic tests. All pregnant women must be informed about prenatal diagnosis. Screening is in principle to be avoided in connection with prenatal diagnosis. Preimplantation diagnosis may only be used for the diagnosis of serious, progressive, hereditary diseases, which lead to premature death and for which there is no cure or treatment.

-

National Board of Health and Social Welfare, Genetics in Health Care: Guidelines, 1999

-

The Agreement between the Swedish government and the Association of insurance companies, 1999: According to this agreement, the use of information about an individual that has been obtained by studying his genetic characteristics other than for medical purposes is prohibited. This agreement is valid to the year 2002.

Switzerland

-

The Swiss Federal Constitution, 1992: The Constitution provides laws on human genetic practice and medical-assisted procreation. Article 119 (introduced in 1992 as article 24 novies, old numbering) paragraph 2 states that the genetic make-up of an individual may be investigated, registered or divulged only with his consent or on the basis of a legal prescription. Article 24 novies forbids preimplantation diagnosis in either clinical or research settings.

-

The Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, Medical–ethical Guidelines for Genetic Investigations in Humans, Approved by the Senate of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences on 3 June 1993: Although there are no official national standards for genetic counselling, the medical–ethical guidelines define the content of genetic counselling in connection with genetic investigation for all physicians.172 The medical–ethical guidelines also define the spectrum of activities belonging to genetic services in general. Quality control standards exist for laboratory investigations.

The Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences guidelines are not legally binding, unless cantonal legislation gives them binding force.

-

Bill regarding Genetic Investigations in Humans, September 1998: This bill has not yet been debated in Parliament. Section 2 allows genetic investigations for medical purposes. Article 10 describes conditions for genetic screening.

The Netherlands

-

The Population Screening Act, 1992 (1996): This act states that screening by means of ionizing radiation, screening for cancer and screening for serious disorders for which there is no treatment are not allowed without ministerial approval, based on the advice and assessment of the Health Council. A license may be refused if the screening programme is scientifically unsound, if it conflicts with statutory regulations or if the risks are found to outweigh any benefits.

-

The Health Council of The Netherlands: Committee Genetic Screening, Genetic Screening, The Hague, 1994: See the section on The Health Council of The Netherlands: Committee Genetic Screening, Genetic Screening.

The United Kingdom

Following the publication of the House of Commons Select Committee on Science and Technology's report (1995), the Department of Health established an advisory sub-committee, The Human Genetics Advisory Commission, which provides advice relating to genetic testing and screening. In 1998, The United Kingdom planed to introduce a new Data Protection Act to implement the terms of the Privacy Directive enacted by the European Union in 1995.112 The aim of this Directive is the harmonization of data protection laws in Europe in order to facilitate the development of medical research while maximizing the protection of individual privacy.

-

Royal College of Physicians, Prenatal Diagnosis and Genetic Screening Community and Service Implications, London, 1989

-

Royal College of Physicians, Purchasers' Guidelines to Genetic Services in the NHS, London, 1991

-

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics, Genetic Screening: Ethical Issues, 1993: See the section on The Nuffield Council on Bioethics, Genetic Screening: Ethical Issues.

-

Working Party of The Clinical Genetics Society, A Report on Genetic Testing of Children, 1994

-

House of Commons Select Committee on Science and Technology,173 human Genetics: the Science and Its Consequences, Third Report, HMSO, 1995: This report examines the ethical issues arising from genetic technology and recommends the setting up of a Human Genetics Commission to regulate the advance of genetic technology.

-

The British Hyperlipidaemia Association, Screening for hyperlipdemia in childhood: Recommendations, 1996

-

The Advisory Committee of Genetic Testing, Code of Practice and Guidance on Human Genetic Testing Services Supplied Direct to the Public, 1997

-

The Advisory Committee on Genetic Testing, A report on Genetic Testing for Late Onset Disorders, 1998: The Advisory Committee on Genetic Testing aims in this report is to set out the issues to be considered before genetic testing for late onset disorders is offered and during the provision of such tests. The major issues relate principally to requests for genetic testing from healthy relatives of patients with a late-onset genetic disorder. Population-based genetic screening, diagnostic testing of symptomatic individuals and genetic susceptibility testing for common disorders are briefly considered.

-

The Royal College of Physicians, Clinical Genetic Services: Activity, Outcome, Effectiveness and Quality, London: Royal College of Physicians, 1998

-

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics, Mental Disorders and Genetics: The Ethical Context, 1998

-

Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority, Code of Practice, 1998

-

Genetic Interest Group, Guidelines for Genetic Services, London, G.I.G., 1998

-

Genetic Interest Group, Confidentiality Guidelines, London, G.I.G., 1998

-

General Medical Council, Seeking patients' consent: the ethical considerations, London: General Medical Council, 1999: This guidance on screening spells out what this should include: the purpose of the screening, the likelihood of positive/negative results, the uncertainties and risks attached to the screening process, any significant medical, social, or financial implications of screening for the particular condition or predisposition, and follow-up plans, including the availability of counselling and support services.

-

Department of Health, Second Report of the UK National Screening Committee, London, Department of Health, 2000: This report contains five chapters: (1) screening policy-making – getting research into practice; (2) organizing screening programmes; (3) the NSC's forward programme; (4) a protocol for pilot management; and (5) the NSC's recommendations since 1998. The NSC's recommendations are for adult programmes (abdominal aortic aneurysms, diabetic retinopathy, vascular disease, osteoporosis, cardiomyopathy, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer), antenatal programme (syphilis) and child health programme.

European institutions

-

Council of Europe, Recommendation on Prenatal Genetic Screening, Prenatal Genetic Diagnosis and Associated Genetic Counselling, 1990 174

-

Council of Europe,175 Recommendation on genetic testing and screening for health-care purposes of the European Committee of Ministers (1992, n. R92, 3): All members of the Council of Europe adopted this Recommendation, except the Netherlands.

-

Council of Europe, Recommendation on Screening as a Tool of Preventive Medicine of the European Committee of Ministers, 1994 176

-

Council of Europe, Privacy Directive 94/46, 1995

-

Council of Europe,177 Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine, 1997: The Convention is the first internationally-binding legal text designed to protect people against the misuse of biological and medical advances. This text has legal effect in the Council of Europe's member States that have ratified it. Each state then has to bring its laws into line with the Convention. Belgium, Germany, Ireland, and the United Kingdom have not yet signed the Convention and it is no force until it is signed and implemented into the national law.

The Convention sets out to preserve human dignity, rights and freedoms, through a series of principles and prohibitions. It does not refer explicitly to genetic screening, at most according to Article 5, a genetic test ‘may only be carried out after the person concerned has given free and informed consent to it’; according to Article 12, ‘tests which are predictive of genetic diseases or which serve either to identify the subject as a carrier of a gene responsible for a disease or to detect a genetic predisposition or susceptibility to a disease may be performed only for health purposes or for scientific research linked to health purposes, and subject to appropriate genetic counselling’. The restriction of genetic diagnostics to health or scientific purposes is reinforced by Article 11 that states that ‘any form of discrimination against a person on grounds of his or her genetic heritage is prohibited’. However, the Convention does not say whether individuals who have had a genetic test for health or scientific purposes will be required to disclose the results of that test to an insurance company or an employer.

The Convention has endorsed the Council of Europe recommendations on genetic screening.

-

Council of Europe, Recommendation 1512 on the protection of the human genome, 2001

Australia

-

Human genetic Society of Australasia, Newborn Screening, 1999: The HGSA proposed general recommendations for newborn screening: Newborn screening is recommended provided that: (i) there is benefit for the individual from early diagnosis. (ii) The benefit is reasonably balanced against financial and other costs. (iii) There is a reliable test suitable for newborn screening. (iv) There is a satisfactory system in operation to deal with diagnostic testing, counselling, treatment and follow-up of patients identifies by the test.

-

Human Genetic Society of Australasia, Guidelines for the Practice of Genetic Counselling, 1999: This guidelines concerns the general practice of genetic counselling. However, the following citation refers to screening tests: ‘Screening tests are non-diagnostic, population-based tests providing the client with a personalised risk. When performed prenatally, screening tests may identify fetal abnormalities or reveal an increased risk of fetal abnormalities. When performed post-natally, the aim of genetic screening is to identify individuals at increased risk of developing symptoms of a disorder in the future, with a view to offering intervention eg, newborn screening. The nature of a screening test should be clearly distinguished from a diagnostic test to the client. Appropriate written and/or verbal information should be provided prior to testing. Support and counselling should be made available to persons receiving a high-risk result so that future options are understood.’

United States of America

-

The ASHG Policy Statement for Maternal Serum alpha-fetoprotein Screening Programs and Quality Control for Laboratories Performing Maternal Serum and Amniotic Fluid alpha-fetoprotein Assays, 1987

-

Statement of The ASHG on Cystic Fibrosis Carrier Screening, 1990

-

Statement of The ASHG on Cystic Fibrosis Carrier Screening, 1992

-

American Medical Association, E-2.137 Ethical Issues in Carrier Screening of Genetic Disorders, 1994: The Association recommends that all carrier testing must be voluntary, and informed consent from screened individuals is required. Confidentiality of results is to be maintained. Results of testing should not be disclosed to third parties without the explicit informed consent of the screened individual. Patients should be informed as to potential uses for the genetic information by third parties, and whether other ways of obtaining the information are available when appropriate. Carrier testing should be available uniformly among the at-risk population being screened. One legitimate exception to this principle is the limitation of carrier testing to individuals of childbearing age. In pursuit of uniform access, physicians should not limit testing only to patients specifically requesting testing. If testing is offered to some patients, it should be offered to all patients within the same risk category. The direction of future genetic screening tests should be determined by well thought out and well-coordinated social policy. Third parties, including insurance companies or employers, should not be permitted to discriminate against carriers of genetic disorders through policies that have the ultimate effect of influencing decisions about testing and reproduction.

-

The ACMG Clinical Practice Committee, Principles of screening, 1997: The American College emphasizes the following points:

-

A screening programme should have a clearly defined purpose, whether the purpose is research or medical care

-

A screening programme is more than a laboratory test. Therefore, follow-up evaluation and counselling by genetic professionals must be guaranteed.

-

A screening programme should be reviewed by the appropriate board and be evaluated periodically to determine if it is meeting its goals.

-

-

The ACMG, Policy Statement: Fragile X Syndrome – Diagnostic and Carrier Testing, 1997

-

The ACMG, Standards and Guidelines for Clinical Genetics Laboratories, Second Edition, 1999: These voluntary standards are an educational resource to assist medical geneticists in providing accurate and reliable diagnostic genetic laboratory testing consistent with currently available technology and procedures in the areas of clinical cytogenetics, biochemical genetics and molecular diagnostics. These standards establish minimal criteria for clinical genetics laboratories. The Standards should not be considered inclusive of all proper procedures and tests or exclusive of other procedures and tests that are reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The accuracy and dependability of all procedures should be documented in each laboratory. This should include in-house validation and/or references to appropriate published literature. Specialized testing, not available to all laboratories, requires appropriate and sufficient documentation of effectiveness to justify its use. In determining the propriety of any specific procedure or test, the medical geneticist should apply his/her own professional judgment to the specific circumstances presented by the individual patient or specimen. Medical geneticists are encouraged to document the reasons for the use of a particular procedure or test, whether or not it is in conformance with these Standards. These Standards will be reviewed and updated periodically to assure their timeliness in this rapidly developing field.

-

The ACMG, Laboratory Standards and Guidelines for Population-based Cystic Fibrosis Carrier Screening, 2001: The Committee recommends that CF carrier screening be offered to non-Jewish Caucasians and Ashkenazi Jews, and made available to other ethnic and racial groups who will be informed of their detectability through educational brochures, the informed consent process, and/or other efficient methods. For example, Asian Americans and Native Americans without significant Caucasian admixture should be informed of the rarity of the disease and the very low yield of the test in their respective populations. Testing should be made available to African Americans, recognizing that only about 50% of at-risk couples will be detected. An educational brochure and a consent form which recites this information as well as a sign-off for those choosing not to be tested after reading these materials is being prepared by the Working Group on Patient Education and Informed Consent.

-

American Medical Association, Report 4 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (I-01) Newborn Screening: Challenges for the Coming Decade, 2001: The AMA:

-

1)

Supports the report from the Newborn Screening Task Force, ‘Serving the Family from Birth to the Medical Home: A Report from the Newborn Screening Task Force,’ and recognizes the authors of this report as the major stakeholders in the field of newborn.

-

2)

Supports the Health Resources and Services Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the American College of Medical Genetics as they study the process of standardization of outcomes and guidelines for state newborn screening programs.

-

3)

Will monitor developments in newborn screening and revisit the topic as necessary.

-

1)

-

American Academy of Pediatrics, Ethical Issues With Genetic Testing in Pediatrics (RE9924), 2001: The AAP has adopted these recommendations:

-

1)

Established newborn screening tests should be reviewed and evaluated periodically to permit modification of the programme or elimination of ineffective components. The introduction of new newborn screening tests should be conducted through carefully monitored research protocols.

-

2)

Genetic tests, like most diagnostic or therapeutic endeavors for children, require a process of informed parental consent and the older child's assent. Newborn screening programmes are encouraged to evaluate protocols in which informed consent from parents is obtained. The frequency of informed refusals should be monitored. Research to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of informed consent for newborn screening is warranted.

-

3)

The AAP does not support the broad use of carrier testing or screening in children or adolescents. Additional research needs to be conducted on carrier screening in children and adolescents. The risks and benefits of carrier screening in the pediatric population should be evaluated in carefully monitored clinical trials before it is offered on a broad scale. Carrier screening for pregnant adolescents or for some adolescents considering pregnancy may be appropriate.

-

4)

Genetic testing for adult-onset conditions generally should be deferred until adulthood or until an adolescent interested in testing has developed mature decision-making capacities. The AAP believes that genetic testing of children and adolescents to predict late-onset disorders is inappropriate when the genetic information has not been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality through interventions initiated in childhood.

-

5)

Because genetic screening and testing may not be well understood, pediatricians need to provide parents the necessary information and counseling about the limits of genetic knowledge and treatment capabilities, the potential harm that may be done by gaining certain genetic information, including the possibilities for psychological harm, stigmatization, and discrimination, and medical conditions and disability and potential treatments and services for children with genetic conditions. Pediatricians can be assisted in managing many of the complex issues involved in genetic testing by collaboration with geneticists, genetic counsellors, and prenatal care providers.

-

6)

The AAP supports the expansion of educational opportunities in human genetics for medical students, residents, and practicing physicians and the expansion of training programmes for genetic professionals.

-

1)

International organizations

-

WHO, Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease, Geneva: WHO, 1968: See the section on ‘WHO guidelines for screening for Disease’.

-

Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences, The Declaration of Inuyama, Human Genome Mapping, Genetic Screening and Gene Therapy, Geneva, 1990: The CIOMS recommended that: ‘The central objective of genetic screening and diagnosis should always be to safeguard the welfare of the person tested: test results must always be protected against unconsented disclosure, confidentiality must be ensured at all costs, and adequate counselling must be provided.’

-

WHO, Community Genetics Services in Europe, Geneva: WHO, 1991

-

UNESCO, International Bioethics Committee, 178 Report of the Working Group on Genetic Screening and Testing, 1994

-

UNESCO, Report of Subcommittee on Bioethics and Population Genetics, Bioethics and Human Population Genetics Research, 1995

-

WHO, Guidelines on Ethical Issues in Medical Genetics and the Provision of Genetic Services, Geneva: WHO, 1995

-

WHO Technical Report Series, Control of Hereditary Diseases, Geneva: WHO, 1996

-