Abstract

Purpose

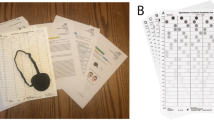

To determine the ability of the newly developed internet-based Spaeth/Richman Contrast Sensitivity (SPARCS) test to assess contrast sensitivity centrally and peripherally in cataract subjects and controls, in comparison with the Pelli–Robson (PR) test.

Methods

In this prospective cross-sectional study, cataract subjects and age-matched normal controls were evaluated using the SPARCS and PR tests. Contrast sensitivity testing was performed in each eye twice in a standardized testing environment in randomized order. SPARCS scores were obtained for central, right upper (RUQ), right lower (RLQ), left upper (LUQ), and left lower quadrants (LLQ). PR scores were obtained for central contrast sensitivity. PR and SPARCS scores in cataract subjects were compared with controls. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and Bland Altman analysis were used to determine test–retest reliability and correlation.

Results

A total of 162 eyes from 84 subjects were analyzed: 43 eyes from 23 cataract subjects, and 119 eyes from 61 controls. The mean scores for SPARCS centrally were 13.4 and 14.5 in the cataract and control groups, respectively (P=0.001). PR mean scores were 1.31 and 1.45 in cataract and control groups, respectively (P<0.001). ICC values for test–retest reliability for cataract subjects were 0.75 for PR and 0.61 for the SPARCS total. There was acceptable agreement between the ability of PR and SPARCS to detect the effect of cataract on central contrast sensitivity.

Conclusions

Both SPARCS and PR demonstrate a significant influence of cataract on contrast sensitivity. SPARCS offers the advantage of determining contrast sensitivity peripherally and centrally, without being influenced by literacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Elliott DB . Evaluating visual function in cataract. Optom Vis Sci 1993; 70: 896–902.

Bernth-Petersen P . Visual functioning in cataract patients. Methods of measuring and results. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1981; 59: 198–205.

Richman J, Spaeth GL, Wirostko B . Contrast sensitivity basics and a critique of currently available tests. J Cataract Refract Surg 2013; 39: 1100–1106.

Ginsburg AP . Contrast sensitivity and functional vision. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2003; 43: 5–15.

Wood JM . Age and visual impairment decrease driving performance as measured on a closed-road circuit. Hum Factors 2002; 44: 482–494.

West SK, Rubin GS, Broman AT, Munoz B, Bandeen-Roche K, Turano K . How does visual impairment affect performance on tasks of everyday life? The SEE Project. Salisbury Eye Evaluation. Arch Ophthalmol 2002; 120: 774–780.

Owsley C, Sloane ME . Contrast sensitivity, acuity, and the perception of 'real-world' targets. Br J Ophthalmol 1987; 71: 791–796.

Rubin GS, Roche KB, Prasada-Rao P, Fried LP . Visual impairment and disability in older adults. Optom Vis Sci 1994; 71: 750–760.

Chylack LT Jr., Padhye N, Khu PM, Wehner C, Wolfe J, McCarthy D et al. Loss of contrast sensitivity in diabetic patients with LOCS II classified cataracts. Br J Ophthalmol 1993; 77: 7–11.

Pelli D, Robson J . The design of a new letter chart for measuring contrast sensitivity. Clin Vision Sci 1988; 187–199.

Richman J, Zangalli C, Lu L, Wizov SS, Spaeth E, Spaeth GL . The Spaeth/Richman contrast sensitivity test (SPARCS): design, reproducibility and ability to identify patients with glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2015; 99 ((1)): 16–20.

Bland JM, Altman DG . Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986; 1: 307–310.

Elliott DB, Hurst MA, Weatherill J . Comparing clinical tests of visual function in cataract with the patient's perceived visual disability. Eye (Lond) 1990; 4: 712–717.

Adamsons I, Rubin GS, Vitale S, Taylor HR, Stark WJ . The effect of early cataracts on glare and contrast sensitivity. A pilot study. Arch Ophthalmol 1992; 110: 1081–1086.

Shandiz JH, Derakhshan A, Daneshyar A, Azimi A, Moghaddam HO, Yekta AA et al. Effect of cataract type and severity on visual acuity and contrast sensitivity. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2011; 6: 26–31.

Cheng Y, Shi X, Cao XG, Li XX, Bao YZ . Correlation between contrast sensitivity and the lens opacities classification system III in age-related nuclear and cortical cataracts. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013; 126: 1430–1435.

Elliott DB, Situ P . Visual acuity versus letter contrast sensitivity in early cataract. Vision Res 1998; 38: 2047–2052.

Pesudovs K, Hazel CA, Doran RM, Elliott DB . The usefulness of Vistech and FACT contrast sensitivity charts for cataract and refractive surgery outcomes research. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 11–16.

Faria BM, Duman F, Zheng CX, Waisbourd M, Gupta L, Ali M et al. Evaluating contrast sensitivity in age-related macular degeneration using a novel computer-based test, the Spaeth/Richman Contrast Sensitivity test. Retina 2015; 35 ((7)): 1465–1473.

Rubin GS, West SK, Munoz B, Bandeen-Roche K, Zeger S, Schein O et al. A comprehensive assessment of visual impairment in a population of older Americans. The SEE Study. Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997; 38: 557–568.

Furuskog P, Nilsson BY . Contrast sensitivity in patients with posterior chamber intraocular lens implants. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1988; 66: 438–444.

Rubin GS, Adamsons IA, Stark WJ . Comparison of acuity, contrast sensitivity, and disability glare before and after cataract surgery. Arch Ophthalmol 1993; 111: 56–61.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Ben Leiby, PhD for contributing to statistical analysis and Dr Michael Waisbourd, MD for his support in manuscript editing and preparation. Commercial Relationships Disclosure: George Spaeth: Consultant for Allergan and Merck. Financial support from Allergan and Merck. Financial support was provided by Pfizer, New York, NY, USA (Grant # WS698663). Glaucoma Service Foundation to Prevent Blindness.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

George Spaeth, Eric Spaeth, and Jesse Richman developed and patented the Spaeth/Richman Contrast Sensitivity test (SPARCS). Eric Spaeth, Patent # 8.042,946; Jesse Richman, MD, Patent # 8.042,946; George L Spaeth, MD, Patent # 8.042,946.

Additional information

This study was presented as a poster at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology in Orlando, FL, USA on May 4, 2014.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, L., Cvintal, V., Delvadia, R. et al. SPARCS and Pelli–Robson contrast sensitivity testing in normal controls and patients with cataract. Eye 31, 753–761 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.319

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.319

This article is cited by

-

Impact of blepharoptosis surgery on vision-related quality of life and its correlation with contrast sensitivity changes

International Ophthalmology (2025)

-

Test-retest repeatability and agreement of the quantitative contrast sensitivity function test: towards the validation of a new clinical endpoint

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2024)

-

Analysing the change in contrast sensitivity post-travoprost treatment in primary open-angle glaucoma patients using Spaeth Richman contrast sensitivity test

International Ophthalmology (2022)

-

Lighting conditions and perceived visual function in ophthalmic conditions

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2021)

-

The effect of reduced contrast sensitivity on colour vision testing

Eye (2019)