Abstract

Purpose: To characterize current practices and attitudes regarding testing adolescents for carrier status.

Methods: Electronic survey of 294 genetic service providers from various professional organizations. Testing for predisposition and presymptomatic conditions was excluded from this study.

Results: Eighty-three percent of providers had received requests to test adolescents for carrier status. Of these, 84% have performed testing. Providers cited adolescent desire, sexual activity/pregnancy, and adolescent competence as the main reasons for testing. Some providers who performed testing found the current guidelines unhelpful.

Conclusion: Testing adolescents for carrier status is common for at least some conditions. The guidelines regarding genetic testing of adolescents may need to be updated to reflect current concerns and practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Genetic testing is no longer a new concept. Each day practitioners offer individuals genetic tests that are relatively simple in technique, but genetic testing may carry a myriad of medical, social, ethical, and legal implications. Due to the special considerations and protections society provides to minors, one of the most sensitive and debated aspects of genetic testing relates to children and adolescents. Most discussion and literature about testing minors for carrier status reflects on the balance of potential benefits and burdens, such as emotional relief, informed life planning, negative self-image, and loss of autonomy.1–8 These benefits and burdens of carrier testing are often related to psychosocial concerns and are thus subjective, making them difficult to compare.1

In an effort to address how to balance the implications involved in testing a minor for carrier status, several professional health care organizations developed guidelines in this area.2–4 The document Points to Consider: Ethical, Legal and Psychosocial Implications of Genetic Testing in Children and Adolescents jointly published in 1995 by the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) and the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) has been considered an authoritative statement regarding the testing of minors.2 The ASHG/ACMG statement acknowledges that psychosocial factors influence genetic testing decision making by affirming that “substantial psychosocial benefits to the competent adolescent” may justify testing for any condition. However, the guidelines are specific in concluding that when the benefits of genetic testing “will not accrue until adulthood, as in the case of carrier testing … genetic testing generally should be deferred.”2 Nevertheless, previous studies have demonstrated that a broad range of genetic health care providers around the world and 38% of genetic service providers in the United States received requests to test children and adolescents for carrier status.3,9 A survey of health care professionals in the United Kingdom found that many requests for genetic testing of minors for carrier status are being fulfilled.5

The goal of this study was to examine (1) practices related to testing adolescents for carrier status, (2) attitudes of genetic service providers toward testing adolescents for carrier status, (3) factors influencing decisions regarding testing adolescents for carrier status, and (4) provider views of the 1995 statement on testing adolescents and children. For this study, carrier status applies only to asymptomatic mutations not expected to increase risk of disease in the individual tested but to have implications for that person's risk of having affected children. The ASHG/ACMG statement has separate guidelines for testing adolescents for adult-onset conditions or presymptomatic status. These were not addressed in this study.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Genetic service providers were invited via email to complete an online survey. An e-mail reminder was issued either 2 or 4 weeks after initial contact. Data collection occurred during a 5-week period in the spring of 2004. The study was approved by the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center institutional review boards.

Diplomates of the American Board of Medical Genetics (ABMG), full members of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC), and members of the International Society of Nursing in Genetics (ISONG) were invited to participate. The sample was chosen to represent those health care professionals to whom the 1995 guidelines most directly apply. Of the 294 individuals who began the survey, 189 completed it. The questionnaire was divided into several sections. Information from the 105 incomplete surveys was included in the analysis for sections that were completed. If a section was partially completed or blank, that portion of the survey was not included in the analysis.

Survey overview

The survey consisted of 18 close-ended questions that queried respondents on demographics, clinical practice, attitudes toward adolescent testing for carrier status, attitudes regarding adolescent autonomy, factors influencing testing decisions, and familiarity with the 1995 guidelines (Appendix, on-line only). The final question was open ended and asked participants to share comments or further experiences. Some participants automatically skipped sections of the survey based on their answers to specific questions.

Several visual analog scales ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 represented nonagreement and 10 represented complete agreement, were used throughout the survey. Respondents expressed their attitude regarding adolescent autonomy by rating their agreement with three statements adapted from a previous study by Wertz.9 From these ratings, an average adolescent autonomy score was calculated.

Factors influential to decision making were measured by asking subjects to rank the top 5 of 16 factors considered in their most recent clinical case and/or a hypothetical situation. A score of one indicated the most influential factor. All unranked factors were given a score of 6. The factor with the lowest mean score was judged the most influential overall.

Use of the guidelines was assessed by asking each participant to rate the helpfulness of their knowledge of the ASHG/ACMG Points to Consider when considering the issues associated with adolescent genetic testing for carrier status. For this measure, the scores <2 and >8 were most informative because the scale's default score was 5.0.

Statistical methods

Before analysis, frequencies, means, and SDs were computed. For comparisons of groups, χ2 and t test analyses were performed. All statistics were performed using SPSS for Windows version 12.0. Significance was set at the P < 0.05 level.

When asked for what condition carrier testing was performed or declined, some respondents chose “other” and indicated conditions for which testing would be considered predisposition/presymptomatic or medically indicated. These are outside the scope of this study; therefore, they were removed before analysis.

RESULTS

Demographics

Table 1 displays most demographic data. Many physicians (33.3%) had practiced >15 years, whereas only 12.6% of genetic counselors had practiced >15 years. Overall, 3.4% of participants had never practiced genetics clinically. Ninety-three percent of respondents practiced in the United States, 4% practiced in Canada, and 3.1% practiced outside the United States and Canada. Differences and similarities between our sample and the population could not be calculated because demographic data are not kept for all the organizations sampled. However, genetic counselors were overrepresented in our sample.

Clinical practices

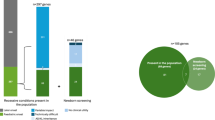

Participants' responses to questions regarding their current practice are given in Table 2. The majority (62.4%) of respondents spent 41% to 100% of their professional time with patients. The percentage of adolescent patients seen per year varied, with the majority (62.1%) of respondents indicating that 1% to 20% of their patients were adolescents. Seventeen percent of genetic service providers indicated that they have no adolescents in their practice. Eighty-three percent of respondents reported at least one request per year to test an adolescent for carrier status. Of those who received requests, 84% had tested an adolescent within the past year, including 19.9% who performed between 81% and 100% of these requests. Figure 1 lists the conditions for which carrier testing was most recently performed (n = 103) and declined (n = 77).

Attitudes

A slight majority of respondents (n = 181) reported that they would perform carrier testing on adolescents for hemophilia (59.7%), fragile X permutation status (57.5%), cystic fibrosis (CF) (56.9%), Tay-Sachs disease (TSD) (55.8%), and balanced chromosome rearrangements (BCR) (55.8%). Fifty percent of respondents reported that they would test for all five conditions, and 32.6% reported that they would not test for any of the five conditions. A minority (17.1%) of respondents reported that they would test an adolescent for some conditions, but would not test for others. Comparing attitudes to reported practices, respondents who reported that they had performed adolescent carrier testing requests (n = 87) typically indicated that they would test an adolescent for carrier status for any of the five conditions: hemophilia (75.0%), TSD (72.7%), fragile X permutation (72.7%), BCR (72.7%), or CF (71.6%). Conversely, respondents who specified that they never performed requests for adolescent carrier testing (n = 24) usually indicated that they would not test an adolescent for any of the conditions listed, CF (79.2%), TSD (79.2%), hemophilia (79.2%), fragile X permutation status (75.0%), or BCR (75.0%). The respondents who indicated that they would test for all the conditions were significantly more likely to have performed testing (n = 62) than those who indicated that they would not test for any of the conditions (χ2 = 27.76, P < 0.001).

With regard to adolescent autonomy, the higher the score, the greater amount of autonomy respondents felt adolescents should have. Twenty-eight percent (n = 49) of respondents had an average adolescent autonomy score of >8 (range: 8.01–9.99), and 9% (n = 16) of respondents scored <5 (range: 1.85–4.99). Of those who received requests and had >8 on the average adolescent autonomy score (n = 34), 41.2% indicated that they performed 81% to 100% of their test requests. The group who received requests and reported <5 on the average adolescent autonomy score (n = 10), all performed <81% of their test requests (P = 0.018).

Factors influencing testing decisions

Respondents who had received requests for adolescent carrier testing in the past year were presented with questions regarding their most recent case. The mean age at the most recent adolescent tested was 15.6 years, and the mean age of the adolescent most recently declined was 13.3 years (t = 10.077, P < 0.001). The reasons that influenced a provider's most recent decision to sanction or to decline a request to test an adolescent for carrier status are listed in order in Tables 3 and 4.

All respondents (N = 180) were asked what factors would influence their decision to test a hypothetical adolescent who was healthy and had no symptoms for carrier status (Table 5). The subgroups who never had a request (n = 34) and those who had requests but performed none (n = 24), reported that sexual activity/pregnancy status would be the most influential factor in their decision making, followed by adolescent competence level/understanding. Adolescent desire for testing was ranked third by those who never had a request. Those who had performed no requests ranked adolescent's age third. Fear of discrimination was ranked last by those who never had a request and 13th by those who had performed no requests. Among the subgroups mentioned above, fear of stigmatization ranked 11th and 10th, respectively, in the order of influence.

Familiarity with the guidelines

The helpfulness of the 1995 ASHG/ACMG guidelines was rated by 175 people. The minimum was 0.0, the maximum was 10.0, and the mean was 5.16 with an SD of 2.72. More participants found the guidelines generally helpful than unhelpful, with 42.9% scoring >5 and 27.4% scoring <5. Nevertheless, more participants reported their knowledge of the ASHG/ACMG statement as very unhelpful (score <2, n = 31 or 17.7%) than those who reported their knowledge as very helpful (score >8, n = 27 or 13.7%). Twelve respondents rated their knowledge as not at all helpful (score = 0), whereas four rated their knowledge as thoroughly helpful (score = 10).

The practices of those who rated their knowledge of the guidelines as very unhelpful or very helpful were separately analyzed. The differences between these two groups were not significant except that those who found the guidelines helpful were more likely to have received a request to test an adolescent for carrier status than those who found the guidelines unhelpful (χ2 = 6.44, P = 0.011). Although not significant, 25% (n = 5) of those who reported their knowledge of the policy as very helpful performed 81% to 100% of requested testing compared to 58.3% (n = 9) of those who reported their knowledge of the policy as very unhelpful (P = 0.13).

DISCUSSION

From this study, it is apparent that a large majority of genetic service providers in the United States receive requests to test adolescents for carrier status. This situation is likely to become more common as testing for more conditions becomes available and as carrier screening becomes a routine part of health care, as is currently the situation for CF.10,11 In the current study, 83% of participants had received requests to test adolescents for carrier status. This percentage is an increase from previous studies.9 Most (84%) genetic service providers who received requests reported testing at least some adolescents. Thus, it is clear that even with published recommendations against testing adolescents for carrier status, such testing is being requested and performed.

The results suggest that the condition for which carrier testing is requested does not greatly affect clinician decision making, at least for the conditions considered by the respondents. Each indication (Fig. 1) was performed and declined with almost the same frequency. The decision appeared to be strongly influenced by participants' previous choices regarding testing. Providers who received requests to test adolescents for carrier status, but who declined requests would typically not test for any of the five conditions; whereas providers who have performed testing would test for all five conditions. It is important to note that all the conditions included in this survey can be quite severe in affected individuals. Thus, it is possible that condition severity may affect clinical decision making, particularly if testing is requested for a condition with relatively mild symptoms. At the time of this survey and presumably when respondents were making decisions about testing adolescents, the medical implications of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and fragile X heterozygosity were not well-known, so it is unlikely that the possible health effects of carrier status for these conditions played a significant role in decision making for this study.

Genetic service providers' decisions to either decline or perform testing appeared to be motivated in part by a desire to protect adolescent autonomy. From the adolescent autonomy ratings, it is clear that providers who afforded adolescents more autonomy were more likely to have facilitated testing when it was requested. Characteristics of autonomous individuals, such as competence and understanding of the information, are highly ranked as real and hypothetical reasons for testing (Tables 3 and 5). Genetic service providers who declined testing ranked “protection of adolescent autonomy” high among their reasons for not testing. This combined with the age differences between adolescents tested and declined implies that providers often agreed to test an older adolescent who requested testing, was believed to be competent, and presented an argument that he or she would use the information. This adolescent was viewed as a responsible decision maker or perhaps had been granted decision-making authority by emancipation due to pregnancy. Providers appeared to be less likely to test adolescents who were ambivalent about testing or who were viewed as too young to understand the implications and thereby less capable of autonomous decision making. The 1995 statement acknowledges that it may be appropriate to test adolescents who are competent, adequately understand the information, and agree to testing.2 Genetic service providers avoid undermining adolescent autonomy, a potential harm of testing often stated in the literature, if such factors influence their decision making.3,6,7,12

The guidelines also note reproductive decision making as a potential benefit of carrier testing but states that adolescents are not engaged in making family-planning decisions, so this point should not greatly influence clinical decision making. However, in 2002, there were an estimated 138,731 births and 252,170 pregnancies among young women age 15 to 17.13 Additionally, most genetic service providers reported adolescent sexual activity/pregnancy status as the factor that would most heavily influence their decision for testing (Table 5). Because the questions were not asked, we cannot say how many of the adolescents or their partners were pregnant in the most recent cases of the respondents or if adolescent carrier testing is more common in a prenatal setting than in conjunction with other types of genetic services. Nevertheless, adolescent sexual activity or pregnancy status directly influences the benefit/cost ratio associated with carrier status testing in terms of reproductive decision making. The benefit of testing may be immediate if the adolescent uses the information to decide whether to have invasive testing, such as amniocentesis, or would consider termination of an affected pregnancy. The adolescent may also require knowledge of carrier risk for physical and emotional preparation of the birth of a potentially ill infant. If knowledge of carrier status is helpful in reproductive decision making, it may be desirable to provide access to testing during adolescence to most effectively promote informed decision making in the present as well as the future.

The 1995 statement discusses discrimination and stigmatization as potential burdens of testing. In the current study, fear of stigmatization and discrimination was regularly ranked among the least influential factors in decision making (Tables 3, 4, and 5). This may indicate that these issues do not cause as much alarm as they did when the 1995 statement was issued, at least for the conditions queried. In this study, the only time that discrimination and stigmatization did not rank among the least influential factors was when respondents reported their reasons for declining to test an adolescent. Even then, concern for discrimination or stigmatization ranked only as moderately influential. This may be due in part to national legislation protecting patient rights or the lack of proven incidents involving genetic discrimination.14 Decreased concern about stigmatization and discrimination may also be due to increasing comfort with genetic testing as a provider's experience increases.

An unexpected finding was the placement of “promotion of identity development/adjustment time” high among factors influential to those who declined testing and low among those who performed testing (Tables 3 and 4). It appears that participants assumed that lack of knowledge of carrier status would promote identity development or that a completely formed identity is desirable before learning carrier status. This view is in contrast to research that suggests adolescents may incorporate carrier status into their identity with greater ease than adults.2,7,15–19 Thus, testing at a time of relative plasticity may have potential benefits.

Some (27.4%) participants were unsatisfied with their knowledge of the ASHG/ACMG statement concerning testing adolescents for carrier status. This could be due to several factors. In the free response section, a number of participants stated that they were unfamiliar with the published statement. Others may believe that the guidelines do not apply to them because they have received no requests or may think that the guidelines do not address the issues they consider during clinical decision making. The fact that those who performed the largest proportion of their requests found their guideline knowledge least helpful suggests that some participants have based testing decisions on issues not addressed by the guidelines. It also may be that some participants simply disagree with the published conclusions regarding testing of adolescents. In contrast, many (42.9%) participants had a positive view of the statement's helpfulness, and those who declined all requests were likely to rate the guideline highly.

Research evaluating the outcomes of carrier testing in minors has been published since the ASHG/ACMG statement was written. These studies indicate that adolescents incorporate the information effectively with minimal negative effects. For example, a French study of adults, who had been identified as carriers of β-thalassemia or sickle cell trait as teenagers, found that 79% of participants remembered their result and 56% took their result into account before having a child.17 In 2003, a study of an Australian Jewish high school genetic screening program for TSD and CF found that 3 to 6 years after screening, 64% of participants had good knowledge of the condition(s) for which they were tested. Participants did not have a high level of concern about their result, and none incorrectly reported their result. All TSD carriers reported that they had told their family, planned to inform their partner of their carrier status, and would use the information to plan pregnancies.20 This research and similar studies indicate that carrier testing information received during adolescence can be assimilated and used during reproductive decision making rather than being frightening, guilt causing, or forgotten.15–18 There has been no published study documenting a high incidence of adolescent depression, anxiety, or discrimination after carrier testing.

The results of this study are limited in generalizability given the lack of comparison of the sample to the target population and not knowing the practice setting (e.g., prenatal, pediatric, adult) of respondents. Data regarding reasons to sanction or decline testing were retrospective, which opens the results to recall bias. The sensitive nature of the topic and the existing guidelines about adolescent genetic testing may cause a halo effect, where genetic service providers submit a response that they believe is desirable rather than an accurate representation of their experience.

Further research in this area is needed. The results of this study should not be applied to predisposition/presymptomatic testing. Carrier screening is clearly different from predisposition/ presymptomatic testing for conditions such as Huntington disease or hereditary cancer syndromes that can affect the future health of the individual tested. Future studies to assess the practices of and reasons for testing minors for these conditions would be helpful to address the full scope of genetic services for adolescents. Additionally, pediatricians and obstetricians will be confronted with questions regarding testing adolescents for carrier status, so it would also be beneficial to characterize their attitudes and practices regarding carrier testing of adolescents and to include them in future discussions of these issues.

In summary, testing adolescents for carrier status is a topic that requires consideration of a multitude of issues. Guidelines for testing should reflect current knowledge and apply to contemporary clinical practices. The strength of the 1995 guidelines is that they address some important issues, have been useful to many practitioners over the past decade, and have raised awareness about decision-making caveats with respect to minors. However, several issues that are highly influential in today's clinical setting are marginalized, and issues of discrimination/stigmatization appear overemphasized given the current legislation and growing experience with testing for carrier status. Therefore, we suggest that the statement be reviewed and updated by the ASHG and ACMG with consideration of the following points: (1) for at least a subset of conditions, carrier testing is commonly requested and performed for adolescents in the clinical setting; (2) carrier testing for adolescents can be performed while protecting adolescent autonomy because many adolescents may be considered competent decision makers, capable of understanding the implications and desire testing; (3) adolescents appear to incorporate testing information into their identity and achieve adjustment relatively quickly with a low risk of negative psychological effects; (4) benefits of testing may be immediate in some situations, such as testing pregnant or sexually active adolescents; and (5) some providers who have tested adolescents find the current guidelines unhelpful in guiding their decision making. Perhaps testing adolescents for carrier status should not be viewed with the assumption that “benefits will not accrue until adulthood.” Instead, testing adolescents for carrier status could be assumed to have an uncertain benefit/harm ratio and the decision of a competent adolescent and his or her family should be respected.2

References

McConkie-Rosell A, Spiridigliozzi GA . “Family matters”: a conceptual framework for genetic testing in children. J Genet Counsel 2004; 13: 9–29.

Points to consider: ethical, legal and psychological implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. Am J Hum Genet 1995; 57: 1233–1241.

Report of a Working Party of the Clinical Genetics Society (UK). The genetic testing of children. J Med Genet 1994; 31: 785–795.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics 2000–2001, Ethical issues with genetic testing in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2001; 107.

Fryer A . Inappropriate genetic testing of children. Arch Dis Child 2000; 83: 7283–7285.

Michie S, Marteau TM . Predictive genetic testing in children: the need for psychological research. Br J Health Psychol 1996; 1: 3–14.

Fanos JH . Developmental tasks of childhood and adolescence: implications for genetic testing. Am J Med Genet 1997; 71: 22–28.

Ross LF, Moon MR . Ethical issues in genetic testing of children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000; 154: 873–879.

Wertz DC, . International perspectives. In: Clarke AJ, editor. The genetic testing of children. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers, 1998.

National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement, genetic testing for cystic fibrosis. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 1529–1539.

Gregg AR, Simpson JL . Genetic screening for cystic fibrosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2002; 29: 329–340.

Fryer A . Genetic testing of children. Arch Dis Child 1995; 73: 97–99.

The Alan Guttmacher Institute, US teenage pregnancy statistics: National and state trends and trends by race and ethnicity. www.guttmacher.org/pubs/2006/09/12/USTPstats.pdf; accessed October 3, 2006.

Shinaman A, Bain LJ, Shoulson I . Preempting genetic discrimination and assaults on privacy: report of a symposium. Am J Med Genet 2003; 120A: 589–593.

Clow CL, Scriver CR . Knowledge about and attitudes toward genetic screening among high-school students: the Tay-Sachs experience. Pediatrics 1977; 59: 86–91.

Jarvinen O, Lehesjoki A, Lindlof M, Uutela A, Kaariainen H . Carrier testing of children for two X-linked diseases: a retrospective study of comprehension of the test results and social and psychological significance of the testing. Pediatrics 2000; 106: 1460–1466.

Lena-Russo D, Badens C, Aubinaud M, Merono F, et al. Outcome of a school screening programme for carriers of haemoglobin disease. J Med Screen 2002; 9: 67–70.

Michie S, Bobrow M, Marteau TM . Predictive genetic testing in children and adults: a study of emotional impact. J Med Genet 2001; 38: 519–528.

Zeesman S, Clow CL, Cartier L, Scriver CR . A private view of heterozygosity: eight-year follow-up on carriers of the Tay-Sachs gene detected by high school screening in Montreal. Am J Med Genet 1984; 18: 769–778.

Barlow-Stewart K, Burnett L, Proos A, Howell V, et al. A genetic screening programme for Tay-Sachs disease and cystic fibrosis for Australian Jewish high school students. J Med Genet 2003; 40: e45.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. John Fletcher for his insights that helped sharpen the focus of this study. They also thank Dr. Judy Bean and Stacy Poe for their assistance with data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

A supplementary Appendix is available via the ArticlePlus feature at www.geneticsinmedicine.org. Please go to the February issue and click on the ArticlePlus link posted with the article in the Table of Contents to view this material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Multhaupt-Buell, T., Lovell, A., Mills, L. et al. Genetic service providers' practices and attitudes regarding adolescent genetic testing for carrier status. Genet Med 9, 101–107 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3180306899

Received:

Accepted:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3180306899

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Experiences of Women Who Have Had Carrier Testing for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Becker Muscular Dystrophy During Adolescence

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2018)

-

“They Just Want to Know” ‐ Genetic Health Professionals' Beliefs About Why Parents Want to Know their Child's Carrier Status

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2017)

-

A qualitative study to explore how professionals in the United Kingdom make decisions to test children for a sickle cell carrier status

European Journal of Human Genetics (2016)

-

Subtle Psychosocial Sequelae of Genetic Test Results

Current Genetic Medicine Reports (2014)

-

Experiences of Teens Living in the Shadow of Huntington Disease

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2008)