Abstract

Purpose:

Newborn screening (NBS) for cystic fibrosis (CF) can identify carriers, which is considered a benefit that enables reproductive planning. We examined the reproductive impact of carrier result disclosure of NBS for CF.

Methods:

We surveyed mothers of carrier infants after NBS (Time 1) and 1 year later (Time 2) to ascertain intended and reported communication of their infants’ carrier results to relatives, carrier testing for themselves/other children, and reproductive decisions. A sub-sample of mothers was also interviewed at Time 1 and Time 2.

Results:

The response rate was 54%. A little more than half (55%) of mothers underwent carrier testing at Time 1; another 40% of those who intended to undergo testing at Time 1 underwent testing at Time 2. Carrier result communication to relatives was high (92%), but a majority of participants did not expect the results to influence family planning (65%). All interviewed mothers valued learning their infants’ carrier results. Some underwent carrier testing and then shared results with family. Others did not use the results or used them in unintended ways.

Conclusion:

Although mothers valued learning carrier results from NBS, they reported moderate uptake of carrier testing and limited influence on family planning. Our study highlights the secondary nature of the benefit of disclosing carrier results of NBS.

Genet Med 19 4, 403–411.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Newborn screening (NBS) aims to reduce childhood morbidity and mortality through early identification and treatment of affected infants.1 This is considered the primary benefit of NBS programs and encourages universal screening of infants for many disorders worldwide. Secondary benefits may also accrue through NBS, such as benefits to the family and society, whereby NBS can inform family planning (“reproductive benefit”) or advance the understanding of disease. Traditionally, these secondary benefits have not been sufficient to justify NBS.2 However, recent scholarly discourse has highlighted reproductive benefits as an increasingly prominent goal of NBS, particularly when the clinical goal of identifying a treatable condition may not be assured.3,4,5,6 One way that reproductive benefits arise through NBS is through the generation of carrier results.

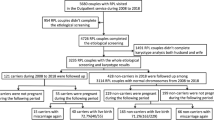

NBS for cystic fibrosis (CF) using typical testing protocols identifies many unaffected carriers of one CF mutation in addition to affected infants; indeed, the majority of infants with false-positive CF NBS results are identified as CF carriers during confirmatory testing.7 In Ontario, CF NBS involves a two-step process of measuring immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) followed by screening the CF transmembrane regulator (CFTR) gene for 39 mutations.8 Confirmatory sweat chloride testing is then performed on screen-positive infants who are subsequently classified as having true-positive, false-positive, or inconclusive (i.e., genetic variants of uncertain significance with or without borderline sweat chloride; Table 1 ) results. Both parents of carrier newborns are offered genetic counseling and carrier testing at no charge as part of the disclosure protocol.

There is long-standing debate about incidental carrier status identification through NBS. First, from an ethical perspective, this information is not typically available without informed consent,9 and carrier testing is not usually pursued in minors.10,11,12 Second, there is inconsistent evidence about the benefits and harms of CF carrier identification through NBS for parents, including the potential to inform family planning and the risk of psychosocial harms.13 Studies have shown that communicating carrier results to parents of infants with false-positive results may cause anxiety.14,15 Although this state tends to be short-lived,15,16,17,18,19 anxiety about the carrier status of their infant persists for a minority of parents and leads to concerns about stigma and the physical health of their carrier child.18,20,21 Third, parents typically state that they want infant carrier information to know reproductive risks,19,21,22,23,24 yet evidence regarding parental use of that information is equivocal. A minority of parents avoided pregnancy after the disclosure of an infant’s carrier status through NBS.22 ( Table 2 ) Uptake of prenatal diagnosis in subsequent pregnancies ranges from 14% to 66%, with higher termination rates of 69% to 100%.25,26,27 Although the majority of parents share their infants’ carrier results with relatives,18,21 evidence of parents’ pursuit of their own carrier testing is inconsistent, varying from 30% to 85% among parents of carrier infants,18,21,22,24 with reduced uptake among next-degree relatives.28 ( Table 2 )

Several studies have documented the reproductive attitudes and behaviors of parents following CF identification,21,25,27,29,30,31,32,33 but these findings are not specific to NBS and are not longitudinal. Thus, there is limited evidence about the nature or extent of the “reproductive benefits” of sharing carrier results of NBS. We examined the uptake of carrier testing, carrier result communication, and impact of carrier results on family planning among parents of a prospective cohort of infants with false-positive CF results identified through NBS. We also examined factors associated with these outcomes. Based on existing evidence,21,25,33,34,35 we hypothesized that carrier status of infants and parity, education, and income levels of mothers would be associated with increased uptake and intentions to pursue carrier testing for themselves, share the results with relatives, and use the results to inform family planning. We also explored participants’ attitudes regarding these behaviors to elucidate the variation in uptake of these behaviors.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This study is part of a prospective, longitudinal, mixed-methods cohort study designed to investigate the impact of NBS for CF on families, health-care providers, and health services in Ontario. We received research ethics board approval from the University of Toronto, the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, and the Hospital for Sick Children.

Sample

We recruited all mothers of infants confirmed to have false-positive results for CF after NBS follow-up at the Hospital for Sick Children during the 18-month data collection period. We excluded infants known to be deceased or in the neonatal intensive care unit, those adopted or involved with child welfare, and based on clinical judgment of inappropriateness (e.g., extreme distress, catastrophic events, significant language barriers).

Data collection

Surveys. We collected structured data using self-administered questionnaires with a modified Dillman approach;36 up to three contacts were made. The Time 1 survey was sent to mothers with infants with false-positive results 4–8 weeks after confirmatory testing; confirmatory testing typically occurred when infants were approximately 4 weeks old. The Time 2 survey occurred 1 year later. Completion and return of the questionnaire package constituted consent to participate.

Questionnaire design. The questionnaire was developed by a multidisciplinary team based on literature review.18,20,21,22 We pretested the questionnaire with new parents recruited from the greater Toronto area (N = 11) through an online mothers’ group to assess comprehension, face, and content validity.

Interviews. We conducted semi-structured, open-ended interviews with the subsample of mothers of infants with false-positive results from the Time 1 and Time 2 cohorts who indicated their willingness on questionnaires and provided informed consent for in-person or telephone interviews. Interviews explored experiences regarding uptake of carrier testing, sharing carrier results with relatives and with their carrier infant, and family planning.

Measures

The measures specific to reproduction included the following: (i) carrier status of the infant; (ii) uptake of carrier testing by mothers and their partners; (iii) communication of infants’ carrier results to relatives; (iv) influence of carrier results on family planning; and (v) carrier testing of other children. Each measure in the questionnaire is detailed in Supplementary Appendix 1 online.

Analysis

Surveys. We calculated the proportion of respondents who indicated yes/no to the test measures. We used chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests to test the hypotheses of associations between participant characteristics and these measures. We considered two-sided P ≤0.05 to indicate statistical significance. Data were managed and analyzed using SPSS 16.0.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

We report cross-sectional analyses for Time 1 and longitudinal results for the subsample of respondents who completed both Time 1 and Time 2 questionnaires. Time 1 questionnaires compare across several study groups (carrier, noncarrier, other/uncertain); Time 2 results are restricted to mothers of carriers because skip patterns prompted noncarrier/other mothers to skip sections pertaining to reproductive risk.

Interviews. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded. We used a thematic approach and applied and modified pre-existing codes from the interview guide pertaining to carrier testing, family communication, and family planning; we allowed new themes to emerge from the data using constant comparison.37 We used Time 1 interviews to identify themes and then searched for confirming/disconfirming evidence in Time 2 interviews. No new themes occurred during Time 2 interviews; therefore, these data are not shown.

Results

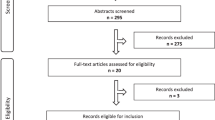

Response rate

We received completed questionnaires from 134 of 246 mothers (54%) during Time 1 and 95 of 216 mothers (44%) during Time 2 (30 fewer mothers were approached at Time 2 because they declined participation during Time 1 and were not approached again during Time 2 or their survey was returned undelivered). We report data for a total of 131 mothers (Time 1), of whom 74 (Time 2) completed Time 1 and Time 2 surveys and responded to the carrier status question during both Time 1 and Time 2.

Carrier status

During Time 1, 77 of 131 mothers (59%) reported that one mutation had been identified in their infant (“mothers of carriers”), 30 (23%) reported no classic mutations (“mothers of noncarriers”), 20 (15%) were “unsure,” and 4 (3%) indicated “Other” (i.e., genetic testing was pending). During Time 2, mothers of carriers comprised 77% (57/74) of the sample, mothers of noncarriers comprised 18% (13/74), and mothers who indicated “unsure/do not know” as their infant’s carrier status comprised 5% (4/74) ( Table 3 ).

Participant characteristics

The characteristics of our survey samples are reported in Table 3 and appear similar to those of the CF carrier population reported in other studies, except that individuals in our samples had higher education levels.18,21,22 There were no significant differences in characteristics between mothers of carriers and other mothers during Time 1 and Time 2, except that at Time 1 mothers of carriers had higher incomes compared to other mothers.

We interviewed 22 mothers of carriers during Time 1 and 25 at Time 2 (7 were interviewed twice). The majority of Time 1 participants were older than 30 years (18/22; 82%), lived in larger cities (16/22; 73%), and earned more than $80,000 (18/21; 86%).

Survey results

Carrier testing uptake. During Time 1, carrier testing uptake was reported by 55% (42/77) of mothers of carriers ( Table 4 ). Four of 30 (13%) mothers of noncarriers and 10/24 (42%) mothers in the “other/do not know” category also reported they had been tested. Mothers also reported fathers’ testing uptake; carrier testing uptake and intentions reported for fathers were similar to mothers’ reported uptake and intentions (data not shown).

Follow-through on intentions to undergo carrier testing. Fifteen mothers of carriers who had not undergone carrier testing during Time 1 intended to and, of those, six (40%) had undergone testing by Time 2 ( Figure 1 ). Of the remaining nine, seven still indicated an intention to undergo testing during Time 2 and two were unsure. The 11 Time 1 mothers of carriers who did not plan to undergo testing or were unsure remained as such at Time 2.

Influence of carrier results on family planning

At Time 1, expectations that an infant’s carrier result would influence family planning did not differ significantly across groups (P = 0.488) (35%, 26/77 mothers of carriers; 27%, 7/30 noncarriers; 25%, 6/24 unsure/other mothers) ( Table 4 ); of these, 18 (69%) mothers of carriers indicated that the results would influence them to have subsequent children, as did 2 (29%) noncarriers and 2 (33%) who were unsure/other ( Table 4 ).

Follow-through on expectations for results to influence family planning. Seventeen mothers expected that their child’s carrier status would influence family planning during Time 1; 11 expected to have subsequent children, of whom 6 (55%) had or still planned to have more children at Time 2 ( Figure 1 ). The majority (>65%) of mothers of carriers did not expect or were unsure whether to expect the results to influence family planning, which remained consistent at follow-up.

Communicating carrier results to relatives

During Time 1, most mothers of carriers had told relatives that they may also be carriers (70/77; 92%), as had 32% (9/30) of mothers of noncarriers and 75% (18/24) of those who were “unsure/other” ( Table 4 ).

Follow-through on intentions to communicate results to family. Only a minority (3/57; 5%) of mothers of carriers did not tell relatives that they may be carriers during Time 1. Of those, all three had told relatives by the time of follow-up ( Figure 1 ).

Carrier testing among other children

Few mothers had their other children undergo carrier testing during Time 1: 8% (3/37) of mothers of carriers, 6% (1/16) of noncarriers, and none of the unsure/other mothers ( Table 4 ).

Factors associated with reproductive behaviors

During Time 1, mothers of carriers were significantly more likely to undergo carrier testing themselves, express an intention to undergo testing, and notify relatives of their infant’s carrier results compared to other mothers (P < 0.001) ( Table 4 ). Primipara mothers were more likely than other mothers to undergo carrier testing and to expect that the results would influence their family planning (P < 0.01; Table 4 and Supplementary Table S1 online).

Qualitative results. Our qualitative analysis extends our survey data, suggesting the existence of two groups of mothers. Although all mothers identified value in learning their infants’ carrier information, some used it in a targeted fashion to inform carrier testing and family communication and others either did not use it or used it in unintended ways.

Reproductive benefit of carrier information

For some mothers, their infants’ carrier results were influential in informing family planning for themselves, which motivated parents to pursue their own carrier testing: “If we were both carriers, we actually kinda decided we wouldn’t have another kid” (ID #253). Carrier results were also perceived as important for relatives’ family planning, which was another motivation to pursue their own carrier testing: “Once we figured out who was the carrier then we discussed [results] with that side of the family...knowledge is power in this case” (ID #50). Mothers reported informing first-degree, second-degree, and third-degree relatives, particularly those planning to have children. Many described the nature of the communication as “talking to [relatives] about it,” whereas others forwarded letters provided by the clinics to the family members who were at risk: “I have plans to send an email around with the information I got from the hospital” (ID #281).

These mothers also valued learning their infants’ carrier results for their children’s future reproductive planning and partner selection. In most cases, parents planned to discuss the results with their children in the future when they were adults and did not perceive this to be “too big of an issue” (ID #198). However, some were concerned that their children would misunderstand the implications or worry: “I would just want to make sure that she’s at a mature enough level that alarm bells don’t go off in her head and she starts stressing about, is this a disease I’m going to get” (ID #141). Learning about infant carrier status sometimes represented an opportunity to learn whether other children are also carriers, which motivated some mothers to undergo carrier testing; however, few also had their other children tested.

Lack of reproductive benefit of carrier information

Other mothers appreciated receiving their infants’ carrier results but did not use the information or used it in an unintended manner. In some instances, this was because they did not plan to have more children. In other instances, the reproductive value of the information was not a focus. This was evident when parents indicated that they pursued carrier testing for themselves out of curiosity or convenience: “I was just curious” (ID #282). Mothers in this group also shared the carrier results of their infants with both sides of the family without attending to which parent was the carrier, and thus which side of the family was specifically at risk: “We’re letting everybody know, but we didn’t feel like we needed to do the testing ourselves to narrow down exactly who to give the information to” (ID #70). These mothers were also uncertain about sharing the carrier results of their infants with their children in the future as adults or gave it little consideration. Finally, these mothers did not expect the results to inform reproductive planning, noting that they would “continue on just like we have” (ID #182).

Discussion

Our study provides the first prospective, longitudinal, mixed-methods data on the reproductive impact of carrier results of NBS for CF. Our results suggest that the reproductive benefits of CF carrier disclosure through NBS among mothers of CF carrier infants are not uniform or consistent. Carrier result communication to relatives was high (92%), and some found the information influential in informing their family planning. However, there was moderate carrier testing uptake (55%), and the majority of participants did not expect the results to influence family planning (65%). Interviews also identified a lack of utility in family planning for some because of life stage. Finally, carrier results were sometimes used in unintended ways: some parents tested their other children and noncarriers informed their relatives that they may be carriers of CF. In addition to challenging international guidelines on carrier testing of minors, these actions may prompt unnecessary use of health-care services or lead to concern among relatives. Given the moderate levels of utility and unintended consequences, our study highlights the secondary nature of the benefits arising from the generation of carrier results from NBS.

Our results are consistent with literature reporting that the majority of parents share the carrier results of their infants with relatives18,21 and that the minority indicate that the results influence decisions to have more children.21,22,25,26 Our maternal carrier testing uptake rate reflects the median reported among parents of carrier infants (30–85%; Table 2 ); this was associated with parity of mothers and the carrier status of their infants. Only one other study compared hypothetical and reported reproductive behaviors, but these were among parents of children with CF and were restricted to use of prenatal testing and termination of pregnancy.26 Thus, our study provides novel results for the intended versus actual uptake of carrier testing and for communication and influence on family planning among parents of carrier infants identified through NBS, the associated factors, and qualitative insights into the variation in behaviors reported in the literature (summarized in Table 2 ).

Our study also revealed some unintended consequences of disclosure of CF carrier results. First, some mothers “told everyone” in their families that they may be CF carriers without confirming which side was at risk. This may create more carrier testing and use of counseling services than would otherwise be necessary. Second, there appears to be evidence of some confusion because mothers of noncarrier infants also reported pursuing carrier testing (13%) and telling relatives they may be carriers (32%), which is inconsistent with guidelines.38 These results indicate a need for improved parental understanding of the implications of noncarrier results. Equipping primary care providers with detailed information about NBS, carrier results, and their reproductive implications are additional avenues to ensure patient understanding because primary care providers often support patients with positive NBS results. Third, a minority of mothers appear to be testing their other children for carrier status. This reveals fundamental challenges of carrier identification through NBS, which may create disparities in access to carrier information between newborns and their older siblings39 and conflicts with existing policies and norms that advise against carrier testing of asymptomatic children.9

Our results provide timely contributions to the evidence base regarding the reproductive impact of sharing carrier results identified through NBS in light of ongoing expansions of NBS worldwide. Our findings raise broader questions about the potential reproductive benefit derived from carrier disclosure as a result of NBS and warrant consideration in policy decisions supporting expanded screening programs. Although mothers valued learning the carrier results of their infants, our study demonstrates moderate intended and reported testing uptake and limited influence on family planning. These results suggest that carrier results should be considered a secondary benefit and thus support previous calls to consider them “additional” or “limited secondary” benefits.21,25

There are several limitations to our study. One year may not be sufficient time to assess maternal carrier testing uptake. We did not assess the mothers’ understanding of carrier status. However, virtually all parents with false-positive results in Ontario are offered free genetic counseling and carrier testing. Therefore, access to genetic testing and counseling or a lack of understanding of the reproductive implications should not represent major confounders in our study. Further, the interviews provide additional support of the mothers’ understanding of the implications of their infants’ carrier status. Finally, although our response rate was modest, it is consistent with, if not higher than, those of similar population-based surveys among CF cohorts (e.g., 37%,22 45%,18 53%40). Furthermore, our study provides the first prospective, longitudinal, mixed-methods results regarding the reproductive impact of carrier results of newborn screening for CF.

Limitations notwithstanding, our study provides a timely contribution to the evidence base for the “reproductive benefits” of sharing carrier results to inform NBS policy. Carrier identification through NBS may motivate carrier testing and family communication, but it does not necessarily influence family planning or reproductive behaviors. If the influence of carrier status on family planning is a proxy for the value of carrier information obtained through NBS, then this benefit is achieved for only a minority of individuals, thus suggesting that it should maintain its historic status as a secondary benefit of NBS.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Wilson JMG, Jungner, G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1968.

Kass NE. An ethics framework for public health. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1776–1782.

Bombard Y, Miller FA, Hayeems RZ, Avard D, Knoppers BM. Reconsidering reproductive benefit through newborn screening: a systematic review of guidelines on preconception, prenatal and newborn screening. Eur J Hum Genet 2010;18:751–760.

Bombard Y, Miller FA, Hayeems RZ, et al. Health-care providers’ views on pursuing reproductive benefit through newborn screening: the case of sickle cell disorders. Eur J Hum Genet 2012;20:498–504.

Bailey DB Jr, Skinner D, Warren SF. Newborn screening for developmental disabilities: reframing presumptive benefit. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1889–1893.

Alexander D, van Dyck PC. A vision of the future of newborn screening. Pediatrics. 2006;117:350–354.

Comeau AM, Accurso FJ, White TB, et al.; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Guidelines for implementation of cystic fibrosis newborn screening programs: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation workshop report. Pediatrics 2007;119:e495–e518.

Ooi CY, Castellani C, Keenan K, et al. Inconclusive diagnosis of cystic fibrosis after newborn screening. Pediatrics 2015;135:e1377–e1385.

Bombard Y, Miller FA, Hayeems RZ, et al. The expansion of newborn screening: is reproductive benefit an appropriate pursuit? Nat Rev Genet 2009;10:666–667.

Borry P, Nys H, Dierickx K. Carrier testing in minors: conflicting views. Nat Rev Genet 2007;8:828.

Botkin JR, Belmont JW, Berg JS, et al. Points to consider: ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. Am J Hum Genet 2015;97:6–21.

Miller FA, Robert JS, Hayeems RZ. Questioning the consensus: managing carrier status results generated by newborn screening. Am J Public Health 2009;99:210–215.

Hayeems RZ, Bytautas JP, Miller FA. A systematic review of the effects of disclosing carrier results generated through newborn screening. J Genet Couns 2008;17:538–549.

Tluczek A, Mischler EH, Farrell PM, et al. Parents’ knowledge of neonatal screening and response to false-positive cystic fibrosis testing. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1992;13:181–186.

Ulph F, Cullinan T, Qureshi N, Kai J. Parents’ responses to receiving sickle cell or cystic fibrosis carrier results for their child following newborn screening. Eur J Hum Genet 2015;23:459–465.

Beucher J, Leray E, Deneuville E, et al. Psychological effects of false-positive results in cystic fibrosis newborn screening: a two-year follow-up. J Pediatr 2010;156:771–6, 776.e1.

Tluczek A, Koscik RL, Modaff P, et al. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: parents’ preferences regarding counseling at the time of infants’ sweat test. J Genet Couns 2006;15:277–291.

Lewis S, Curnow L, Ross M, Massie J. Parental attitudes to the identification of their infants as carriers of cystic fibrosis by newborn screening. J Paediatr Child Health 2006;42:533–537.

Parsons EP, Clarke AJ, Bradley DM. Implications of carrier identification in newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2003;88:F467–471.

Baroni MA, Anderson YE, Mischler E. Cystic fibrosis newborn screening: impact of early screening results on parenting stress. Pediatr Nurs 1997;23:143–151.

Mischler EH, Wilfond BS, Fost N, et al. Cystic fibrosis newborn screening: impact on reproductive behavior and implications for genetic counseling. Pediatrics 1998;102(1 Pt 1):44–52.

Ciske DJ, Haavisto A, Laxova A, Rock LZ, Farrell PM. Genetic counseling and neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis: an assessment of the communication process. Pediatrics 2001;107:699–705.

Tluczek A, Koscik RL, Farrell PM, Rock MJ. Psychosocial risk associated with newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: parents’ experience while awaiting the sweat-test appointment. Pediatrics 2005;115:1692–1703.

Wheeler PG, Smith R, Dorkin H, Parad RB, Comeau AM, Bianchi DW. Genetic counseling after implementation of statewide cystic fibrosis newborn screening: Two years’ experience in one medical center. Genet Med 2001;3:411–415.

Dudding T, Wilcken B, Burgess B, Hambly J, Turner G. Reproductive decisions after neonatal screening identifies cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2000;82:F124–127.

Sawyer SM, Cerritelli B, Carter LS, Cooke M, Glazner JA, Massie J. Changing their minds with time: a comparison of hypothetical and actual reproductive behaviors in parents of children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics 2006;118:e649–e656.

Scotet V, de Braekeleer M, Roussey M, et al. Neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis in Brittany, France: assessment of 10 years’ experience and impact on prenatal diagnosis. Lancet 2000;356:789–794.

McClaren BJ, Metcalfe SA, Aitken M, Massie RJ, Ukoumunne OC, Amor DJ. Uptake of carrier testing in families after cystic fibrosis diagnosis through newborn screening. Eur J Hum Genet 2010;18:1084–1089.

Jedlicka-Köhler I, Götz M, Eichler I. Utilization of prenatal diagnosis for cystic fibrosis over the past seven years. Pediatrics 1994;94:13–16.

Polnay JC, Davidge A, Lyn U C, Smyth AR. Parental attitudes: antenatal diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child 2002;87:284–286.

Borgo G, Fabiano T, Perobelli S, Mastella G. Effect of introducing prenatal diagnosis on the reproductive behaviour of families at risk for cystic fibrosis. A cohort study. Prenat Diagn 1992;12:821–830.

Wertz DC, Janes SR, Rosenfield JM, Erbe RW. Attitudes toward the prenatal diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: factors in decision making among affected families. Am J Hum Genet 1992;50:1077–1085.

Watson EK, Marchant J, Bush A, Williamson B. Attitudes towards prenatal diagnosis and carrier screening for cystic fibrosis among the parents of patients in a paediatric cystic fibrosis clinic. J Med Genet 1992;29:490–491.

Evers-Kiebooms G, Denayer L, Van den Berghe H. A child with cystic fibrosis: II. Subsequent family planning decisions, reproduction and use of prenatal diagnosis. Clin Genet 1990;37:207–215.

Lagoe E, Labella S, Arnold G, Rowley PT. Cystic fibrosis newborn screening: a pilot study to maximize carrier screening. Genet Test 2005;9:255–260.

Dillman D. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Toronto, Canada: John Wiley and Sons, 2000.

Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–340.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 486: update on carrier screening for cystic fibrosis. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:1028–1031.

Noke M, Wearden A, Peters S, Ulph F. Disparities in current and future childhood and newborn carrier identification. J Genet Couns 2014;23:701–707.

Henneman L, Bramsen I, Van Os TA, et al. Attitudes towards reproductive issues and carrier testing among adult patients and parents of children with cystic fibrosis (CF). Prenat Diagn 2001;21:1–9.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP 106505).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table S1

(DOC 45 kb)

Supplementary Appendix 1

(DOC 29 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bombard, Y., Miller, F., Barg, C. et al. A secondary benefit: the reproductive impact of carrier results from newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Genet Med 19, 403–411 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.125

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.125

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Genomic newborn screening for rare diseases

Nature Reviews Genetics (2023)

-

Primary care provider perspectives on using genomic sequencing in the care of healthy children

European Journal of Human Genetics (2020)

-

Coming to terms with the imperfectly normal child: attitudes of Israeli parents of screen-positive infants regarding subsequent prenatal diagnosis

Journal of Community Genetics (2019)

-

The Genomics ADvISER: development and usability testing of a decision aid for the selection of incidental sequencing results

European Journal of Human Genetics (2018)