Abstract

Objective:

Parental eating behavior traits have been shown to be related to the adiposity of their young children. It is unknown whether this relationship persists in older offspring or whether rigid or flexible control are involved. The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that parental eating behavior traits, as measured by the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ), are related to offspring body weight.

Methods:

Cross-sectional anthropometric and TFEQ data from phase 2 and 3 of the Québec Family Study generated 192 parent–offspring dyads (offspring age range: 10–37 years). Relationships were adjusted for offspring age, sex and reported physical activity, number of offspring per family and parent body mass index (BMI).

Results:

In all parent–offspring dyads, parental rigid control and disinhibition scores were positively related to offspring BMI (r=0.17, P=0.02; r=0.18, P<0.01, respectively). There were no significant relationships between cognitive restraint (P=0.75) or flexible control (P=0.06) with offspring BMI. Regression models revealed that parent disinhibition mediated the relationship between parent and offspring BMI, whereas rigid control of the parent moderated this relationship. The interaction effect between parental rigid control and disinhibition was a significant predictor of offspring BMI (β=0.13, P=0.05).

Conclusion:

Family environmental factors, such as parental eating behavior traits, are related to BMI of older offspring, and should be a focus in the prevention of obesity transmission within families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global prevalence of obesity has attained an astounding level with over 600 million adults and ∼40–50 million children being considered obese.1 Genetic and environmental factors are implicated in the multifaceted etiology of obesity. Offspring of overweight and obese parents have an increased chance of being themselves overweight or obese.2 The familial propagation of weight status has both genetic and environmental underpinnings with heritability estimates of body mass index (BMI) as high as 50%.3 Environmental factors, such as the family eating environment, are also undoubtedly involved in the familial transmission of obesity.

Eating behavior traits measured by the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ)4 are known to be related to body weight in adults,5, 6, 7 adolescents8, 9 and children.10, 11 Eating behavior traits also aggregate in families. There is evidence of a genetic transmission of eating behavior from parent to child,12, 13, 14, 15, 16 but transmission is partly influenced by the common family environment,13 specifically for disinhibition.12, 16 As described by Birch et al.17 (Figure 1), parent eating behavior can directly influence the eating behavior of the offspring through social modeling, that is, learning through the observation and imitation of others,18 or indirectly through the child feeding practices of the parent. Eating behavior of the offspring, in turn, may influence their body weight.17

Studies that have identified parental eating behavior traits as a potential factor influencing offspring body weight status have focused mainly on young children (under 6 years), and findings are inconsistent.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Moreover, one study has shown that mother’s disinhibition mediates the relationship between mothers’ and daughters’ body weight status.19 At present, it is unknown if the potential relationship between parent eating behavior traits and offspring BMI exists in older offspring. In addition, to our knowledge, no study has examined the possible effect of parent rigid control, in place of cognitive restraint, on offspring BMI. Rigid control is described as a ‘disturbed eating pattern’ and an unsuccessful approach to weight control24 and may increase one’s susceptibility to overeating and body weight control problems.25 Accordingly, we have recently shown that rigid control and disinhibition is associated to body weight in adolescents.8

The aim of the current study was to test the hypothesis that parental eating behavior traits, specifically rigid control and disinhibition, are associated with BMI of older offspring and mediate the relationship between parent and offspring BMI.

Material and methods

Participants

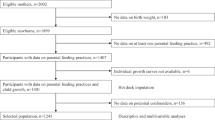

Participants for the current study are from phase II (1989–1995) and III (1997–1995) of the Québec Family Study. Briefly, families of French decent (Caucasian) were randomly recruited from the Québec city area to participate in a longitudinal prospective cohort study with the aim to examine genetic determinants of obesity. Detailed methods of the Québec Family Study are described elsewhere.26 Fifty-nine families with the number of offspring ranging from 1–5, created 192 parent–offspring dyads for analysis (n=58 mothers, n=53 fathers; n=110 offspring; 7 single-parent families). There were seven single-parent families. All adult participants signed an informed consent for themselves and their children as warranted, and the study was approved by the medical ethics committee of Laval University.

Measurements

Parent and offspring body weight and height were measured by standard procedures and BMI was calculated. Physical activity was estimated from a 3-day self-reported physical activity journal, where daily activity was coded every 15 min period using a 9-category scoring system. The 9 categories related to activities of increasing energy expenditure, that is, 1–4 indicating activities of low energy expenditure and 5–9 indicating activities of moderate to high energy expenditure. A total activity score was calculated as the sum of all 9 categories.27

The TFEQ,4 with its subscales,28 was administered at the end of phase II and during phase III and parent TFEQ scores from one phase, either II or III, were used in cross-sectional analyses. The TFEQ measures the eating behavior traits of cognitive restraint, disinhibition and hunger. Cognitive restraint is the intent to restrict energy intake with the purpose of weight control. Disinhibition, in theory, is the lack of inhibition of dietary restraint, but has also been described as ‘opportunistic eating’,29 ‘susceptibility to eating problems’ and ‘emotionally and externally triggered eating’,25 as it can exist in the absence of dietary restraint. Hunger measures one’s susceptibility to feelings of hunger.4 In addition to these main factors, Westenhoefer28 has identified two opposing subscales in the TFEQ restraint construct: flexible and rigid control. The former is described as a healthier approach to weight control, while the latter is described as a ‘disturbed eating pattern’ and an unsuccessful approach to weight control.24

Statistical analyses

Cross-sectional analyses were performed using JMP statistical software (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). Data are presented as either mean (s.d.) or median (interquartile range) for TFEQ scores. Pearson full and partial correlation coefficients were used to examine the individual relationships between parent eating behavior traits and offspring BMI. Multiple regression models were used to examine the main effect of parental rigid control and disinhibition on offspring BMI. In addition, possible interaction effects on offspring BMI were analyzed (between rigid control and disinhibition and between eating behavior traits and parent BMI). Multiple regression prediction equations were used to predict offspring BMI from various levels of rigid control and disinhibition in order to visualize the relationships between parental eating behavior traits and offspring BMI. All analyses were controlled for offspring age, sex and physical activity score, parent BMI and number of offspring per family. In this sample, flexible and rigid control were correlated, but were opposingly related to disinhibition—flexible control negatively related and rigid control positively related. To isolate the effect due to rigid control, all analyses with this measure were controlled for flexible control. All assumptions were verified.

Results

Population characteristics

A total of 192 parent–offspring dyads were available for analysis. The mean number of offspring per family was 2.3 and ranged from 1 to 5. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Median parent eating behavior trait scores range from very low–low for cognitive restraint and its subscales, low–middle for disinhibition and low for hunger.30 Parental rigid control and disinhibition scores were positively related to parent BMI (P=0.01, P<0.0001, respectively; Table 2). There was a significant correlation between offspring and parent BMI (P<0.0001; Table 2). In addition, exploratory data analysis revealed many of the TFEQ scales were correlated (not controlled for parent BMI, Table 2).

Parent eating behavior traits and offspring BMI

Parental rigid control (r=0.17, P=0.02) and disinhibition (r=0.18, P=0.01) scores, but not hunger scores (r=0.04, P=0.57), remained positively related to offspring BMI after controlling for offspring age, sex and physical activity, parental BMI, parent age, parent sex and number of offspring per family. The relationship between parental rigid control and offspring BMI became stronger in addition to being controlled for flexible control (controlled: r=0.20, P=0.005).

All regression models were modest predictors of offspring BMI accounting for, at most, 25% of the variance in offspring BMI (Table 3). In the absence of eating behavior traits, parent BMI and number of offspring were significant predictors of offspring BMI (model 1). Adding cognitive restraint to the regression model revealed it was not a significant predictor of offspring BMI (β=0.03, P=0.75). Both rigid control and disinhibition were significant predictors of offspring BMI (model 2 and 3, Table 3). Similar to the correlation analyses, removing flexible control from the model weakened the effect of rigid control (β=0.37, P=0.08). There were no significant interaction effects between parent BMI and either parental rigid control (β=0.05, P=0.23) or disinhibition (β=0.006, P=0.74), meaning that the effects of rigid control and disinhibition on offspring BMI remain the same for all levels of parent BMI. Regression analysis reveals that disinhibition, and not rigid control, partially mediates the relationship between parent and offspring BMI as the beta estimate of parent BMI was significantly reduced when this variable was included in the model (β=0.17, P=0.05; model 3). This mediation effect, however, was moderated by the rigid control of the parent due to the interaction effect with disinhibition. As expected, all relationships were significantly related to the random effect of family (P<0.0001) and due to the nature of the analyses, this variable was removed to prevent overcorrecting the models.

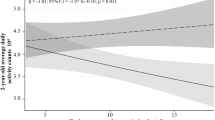

Figure 2 is a visual representation of the predictive effects of the interaction between rigid control and disinhibition on BMI using the model prediction equation. In the absence of disinhibition, the effect of parent rigid control on offspring BMI is attenuated, that is, rigid control moderates this relationship. The same is true for disinhibition—the relationship between parental disinhibition and offspring BMI is stronger with increasing levels of parental rigid control (figure not shown).

The relationship between parent rigid control and offspring BMI as a function of low (0), medium (7) and high (15) parent disinhibition; results were calculated from multiple regression analysis prediction equations controlling for parent BMI (mean 27.8 kg m−2), number of offspring per family (mean 2.3), offspring age (mean 24.9 years), flexible control (2.7) and physical activity score (mean 221.8). The interaction effect between rigid control and disinhibition was significantly related to offspring BMI (P=0.05).

Discussion

In this study, parent–offspring dyads from a family cohort were analyzed to investigate whether parental eating behavior traits are related to offspring BMI. The findings were in line with our hypotheses, whereby parental rigid control and disinhibition were both positively related to offspring BMI, after controlling for important covariates such as parent BMI. In addition, there was a significant interaction effect between rigid control and disinhibition on offspring BMI. Regression analyses revealed that parental disinhibition mediated the relationship between parent and offspring BMI, and rigid control of the parent moderated this effect as parents with high levels of both rigid control and disinhibition have offspring with the highest BMI. Cognitive restraint was not a significant predictor of offspring BMI, which emphasizes the importance of identifying different types of dietary restraint in the context of obesity treatment among families.

The results obtained in the present study are in concordance with some, but not all, studies on this topic. In two cross-sectional studies in young children, significant relationships have been found between maternal disinhibition and body weight measures in their sons20 and daughters19 and which also mediated the mother–daughter body weight relationship in the latter study. Additionally, parents with both high cognitive restraint and high disinhibition had children with the greatest adiposity gains.21 Two studies, however, did not find any significant relationships between parental eating behavior traits and offspring BMI.22, 23 These studies have focused on very young children, whereas the offspring of the present study are much older (mean 24.9 years), thus the underlying relationship may be different. It is difficult to compare the present results with these previous studies. Nonetheless, findings from these studies and the present study suggest the influence of parental eating behavior traits on offspring body weight begins at an early age and may persist to older ages.

In the present study, rigid control and disinhibition were both correlated with offspring BMI. Rigid control, as described by Westenhoefer and Pradel,7 is a ‘pseudo control’ over food intake because it is not planned effectively and is a dichotomous approach to eating (an "all or nothing" approach) that leaves little room for versatility. As such, it has been suggested that high rigid control of eating may lead to ‘overeating’, as measured by the TFEQ disinhibition scale.25 Parents with both high rigid control and high disinhibition likely fluctuate between periods of unstructured, strict self-regulated eating and periods of circumstantial overeating. This suggests that rigid control and disinhibition represent an unhealthy eating behavior profile and individuals with this profile may struggle more with eating and body weight, and display unsuccessful methods of body weight control.24 Findings from this study suggest that not only do rigid control and disinhibition often coexist among parents, but they are codependent (interaction effect) in their association with offspring BMI; parents susceptible to overeating amplifies the relationship between rigid control and offspring BMI (and vice versa). Similar results were found in one study in young children, whereby parental restrictive behavior in the absence of disinhibition had less deleterious effects on offspring body weight.21 In line with the social modeling effect, exposure to this type of eating environment as a child/youth likely has a negative impact on the eating behavior traits of the child/youth and, in turn, a negative influence on their body weight.17 Although the relationship between parent and offspring eating behavior traits cannot be confirmed in our study, previous studies from the same cohort have reported similarities in these traits between parent and offspring,13 and that the heaviest adolescents were characterized by both rigid control and disinhibition.8

Overweight/obese individuals usually report higher scores of rigid control and disinhibition,6, 31 the present study included. This suggests that an unhealthy eating environment exists more in households with overweight/obese parents than parents of healthy weight. This was confirmed in the present study where the family effect was very strong. Therefore, it could be hypothesized that offspring with one or both parents overweight/obese may be at greater risk of obesity through greater exposure to this unhealthy eating environment. In addition, by being predisposed to obesity, offspring may be more vulnerable to the negative effects of an unfavorable eating environment.32, 33 Conversely, the lack of an interaction effect between eating behavior traits and parent weight status on offspring BMI in the present study, suggests the relationship between eating behavior traits on offspring BMI remains the same regardless of parent BMI. However, parent disinhibition mediated the relationship between parent and offspring BMI; whereas rigid control moderated the effect of disinhibition on offspring BMI. Although it is known that obesity has a genetic underpinning,34 these results support the environmental and behavioral propagation of obesity within families. This is important in the context of obesity prevention strategies among families.

The intercorrelations between flexible control, rigid control and disinhibition among the parents make characterizing the parental eating behavior profile complex. In this study, rigid control and flexible control are positively correlated, yet have opposing relationships with offspring BMI and with disinhibition. Rigid control and flexible control are not mutually exclusive, but rather there exists a continuum in the ratio of flexible to rigid control that will differ on an individual basis. For example, an individual with high rigid control and low flexible control will tend to have higher disinhibition than an individual with low rigid control and high flexible control,24 a relationship also observed in our study (data not shown). For this reason, including flexible control in the regression models is important to grasp the full effect of rigid control without the ‘noise’ of flexible control.5 The attenuating effect of flexible control was also likely the reason why cognitive restraint, a scale composed of both rigid and flexible measures, was not a predictor of offspring BMI. The disinhibition scale is frequently used in obesity research as a measure of unhealthy eating behavior or as a measure of trait overeating, but rarely is rigid control considered. These results suggest that future studies should include this subscale when studying the relationship between eating behavior traits and body weight. The moderating effect of parental rigid control on the relationship between parental disinhibition and offspring body weight in the present study needs to be confirmed when examining an individual’s eating behavior traits on their own body weight.

The main limitation of this study is the cross-sectional nature of the data, as there were too few families to test this hypothesis longitudinally. Furthermore, because it was not possible to assess the association between parent and offspring eating behavior traits in this study, it is difficult to validate the social modeling theory discussed in this study, and interpretation of these results needs to remain modest. Nevertheless, the present results in combination with previous research from this cohort8, 13 support the theoretical foundation of this study. Nonetheless, the originality of this study was the investigation of parental rigid and flexible control, in addition to cognitive restraint, on BMI of older offspring whereby parental rigid control, and not cognitive restraint, was related to offspring BMI. This emphasizes the importance to distinguish between general cognitive restraint and the control subscales.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that parents with the combined eating behavior profile of rigid control and disinhibition have the heaviest offspring, regardless of parent weight status, and that these effects are present in older offspring. These behavior traits often coexist and are extant in households of overweight/obese parents but are not limited to these households. Assessing and preventing unhealthy eating behavior traits, specifically those of rigid control and disinhibition, in families may help reduce the incidence of childhood obesity and should not be limited to overweight/obese families.

References

International Obesity Taskforce. The Global Epidemic. 2010 [cited 2011; Available from http://www.iaso.org/iotf/obesity/obesitytheglobalepidemic/.

Whitaker KL, Jarvis MJ, Beeken RJ, Boniface D, Wardle J . Comparing maternal and paternal intergenerational transmission of obesity risk in a large population-based sample. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 91: 1560–1567.

Rice T, Perusse L, Bouchard C, Rao DC . Familial aggregation of body mass index and subcutaneous fat measures in the longitudinal Quebec family study. Genet Epidemiol 1999; 16: 316–334.

Stunkard AJ, Messick S . The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985; 29: 71–83.

Shearin EN, Russ MJ, Hull JW, Clarkin JF, Smith GP . Construct validity of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire: flexible and rigid control subscales. Int J Eat Disord 1994; 16: 187–198.

Provencher V, Drapeau V, Tremblay A, Despres JP, Lemieux S . Eating behaviors and indexes of body composition in men and women from the Quebec family study. Obes Res 2003; 11: 783–792.

Westenhoefer J, Pudel V, Maus N . Some restrictions on dietary restraint. Appetite 1990; 14: 137–141.

Gallant AR, Tremblay A, Perusse L, Bouchard C, Despres JP, Drapeau V . The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire and BMI in adolescents: results from the Quebec Family Study. Br J Nutr 2010; 7: 1–6.

Angle S, Engblom J, Eriksson T, Kautiainen S, Saha MT, Lindfors P et al. Three factor eating questionnaire-R18 as a measure of cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating in a sample of young Finnish females. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2009; 6: 41.

Vogels N, Posthumus DL, Mariman EC, Bouwman F, Kester AD, Rump P et al. Determinants of overweight in a cohort of Dutch children. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84: 717–724.

Shunk JA, Birch LL . Girls at risk for overweight at age 5 are at risk for dietary restraint, disinhibited overeating, weight concerns, and greater weight gain from 5 to 9 years. J Am Diet Assoc 2004; 104: 1120–1126.

Steinle NI, Hsueh WC, Snitker S, Pollin TI, Sakul H, Jean PL et al. Eating behavior in the Old Order Amish: heritability analysis and a genome-wide linkage analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 75: 1098–1106.

Provencher V, Perusse L, Bouchard L, Drapeau V, Bouchard C, Rice T et al. Familial resemblance in eating behaviors in men and women from the Quebec Family Study. Obes Res 2005; 13: 1624–1629.

Neale BM, Mazzeo SE, Bulik CM . A twin study of dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger: an examination of the eating inventory (three factor eating questionnaire). Twin Res 2003; 6: 471–478.

Tholin S, Rasmussen F, Tynelius P, Karlsson J . Genetic and environmental influences on eating behavior: the Swedish Young Male Twins Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2005; 81: 564–569.

de Castro JM, Lilenfeld LR . Influence of heridity on dietary restraint, disinhibition, and perceived hunger in humans. Nutrition 2005; 21: 446–455.

Birch LL, Davison KK . Family environmental factors influencing the developing behavioral controls of food intake and childhood overweight. Pediatr Clin North Am 2001; 48: 893–907.

Bandura A, Walters RH . Social learning and personality development. Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York, 1963.

Cutting TM, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Birch LL . Like mother, like daughter: familial patterns of overweight are mediated by mothers’ dietary disinhibition. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 69: 608–613.

Whitaker RC, Deeks CM, Baughcum AE, Specker BL . The relationship of childhood adiposity to parent body mass index and eating behavior. Obes Res 2000; 8: 234–240.

Hood MY, Moore LL, Sundarajan-Ramamurti A, Singer M, Cupples LA, Ellison RC . Parental eating attitudes and the development of obesity in children. The Framingham Children’s Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000; 24: 1319–1325.

Johannsen DL, Johannsen NM, Specker BL . Influence of parents’ eating behaviors and child feeding practices on children’s weight status. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006; 14: 431–439.

Jahnke DL, Warschburger PA . Familial transmission of eating behaviors in preschool-aged children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008; 16: 1821–1825.

Westenhoefer J, Stunkard AJ, Pudel V . Validation of the flexible and rigid control dimensions of dietary restraint. Int J Eat Disord 1999; 26: 53–64.

Westenhoefer J, Broeckmann P, Munch AK, Pudel V . Cognitive control of eating behavior and the disinhibition effect. Appetite 1994; 23: 27–41.

Bouchard C . Genetic epidemiology, association and sib-pair linkage: results from the Quebec Family Study. In: Bray GA, Ryan DH editors. Molecular and Genetic Aspects of Obesity. Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge, LA pp 470–481 1996.

Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Leblanc C, Lortie G, Savard R, Theriault G . A method to assess energy expenditure in children and adults. Am J Clin Nutr 1983; 37: 461–467.

Westenhoefer J . Dietary restraint and disinhibition: is restraint a homogeneous construct? Appetite 1991; 16: 45–55.

Bryant EJ, King NA, Blundell JE . Disinhibition: its effects on appetite and weight regulation. Obes Rev 2008; 9: 409–419.

Timko A . Norms for the rigid and flexible control over eating scales in a United States population. Appetite 2007; 49: 525–528.

Masheb RM, Grilo CM . On the relation of flexible and rigid control of eating to body mass index and overeating in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2002; 31: 82–91.

Qi L, Cho YA . Gene-environment interaction and obesity. Nutr Rev 2008; 66: 684–694.

Loos RJ, Bouchard C . Obesity-is it a genetic disorder? J Intern Med 2003; 254: 401–425.

Rankinen T, Zuberi A, Chagnon YC, Weisnagel SJ, Argyropoulos G, Walts B et al. The human obesity gene map: the 2005 update. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006; 14: 529–644.

Acknowledgements

AR Gallant is funded by The Quebec Heart and Lung Research Institute. We thank Dr G Theriault, G Fournier, L Allard, M Chagnon and C Leblanc for their contributions to the recruitment and data collection of the Quebec Family Study. The present work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MCG-15187). The Quebec Family Study was supported over the years by multiple grants from the Medical Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (PG-11811, MT-13960 and GR-15187) as well as other agencies. CB is partially funded by the John W Barton, Sr Chair in Genetics and Nutrition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gallant, A., Tremblay, A., Pérusse, L. et al. Parental eating behavior traits are related to offspring BMI in the Québec Family Study. Int J Obes 37, 1422–1426 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.14

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.14

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Obesity and Eating Disturbance: the Role of TFEQ Restraint and Disinhibition

Current Obesity Reports (2019)

-

Intrinsic brain subsystem associated with dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger: an fMRI study

Brain Imaging and Behavior (2017)

-

Mother’s body mass index and food intake in school-aged children: results of the GINIplus and the LISAplus studies

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2014)