Abstract

Objective:

To compare the associations between food environment at the individual level, socioeconomic status (SES) and obesity rates in two cities: Seattle and Paris.

Methods:

Analyses of the SOS (Seattle Obesity Study) were based on a representative sample of 1340 adults in metropolitan Seattle and King County. The RECORD (Residential Environment and Coronary Heart Disease) cohort analyses were based on 7131 adults in central Paris and suburbs. Data on sociodemographics, health and weight were obtained from a telephone survey (SOS) and from in-person interviews (RECORD). Both studies collected data on and geocoded home addresses and food shopping locations. Both studies calculated GIS (Geographic Information System) network distances between home and the supermarket that study respondents listed as their primary food source. Supermarkets were further stratified into three categories by price. Modified Poisson regression models were used to test the associations among food environment variables, SES and obesity.

Results:

Physical distance to supermarkets was unrelated to obesity risk. By contrast, lower education and incomes, lower surrounding property values and shopping at lower-cost stores were consistently associated with higher obesity risk.

Conclusion:

Lower SES was linked to higher obesity risk in both Paris and Seattle, despite differences in urban form, the food environments and in the respective systems of health care. Cross-country comparisons can provide new insights into the social determinants of weight and health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Socioeconomic status (SES), urban form and the food environment can exert a powerful influence on body weights and health.1, 2, 3 Both in France and in the United States, higher obesity rates are associated with lower education and incomes, lower occupational status4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and with lower-quality diets9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 New geospatial analyses of residential neighborhoods in the United States have found higher obesity rates in more deprived and underserved areas.2, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 In particular, food deserts, defined as high poverty areas where the nearest supermarket is >1 mile away, are said to contribute to the American obesity epidemic.20, 21, 24 In France, a study has found that living in low SES neighborhoods (in Paris region) was associated with an increased body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference.25

Most previous studies of the food environment and body weight have measured access to food at some level of geographic aggregation.26, 27 Among measures of food access were density of grocery stores or fast food restaurants per unit area or the road network distance to the supermarket that was closest to the respondent’s home.18, 19, 21, 28, 29, 30, 31

One limitation of purely geographic measures is that they do not reflect the actual food environment of study participants. Indeed, most of the studies lacked any data on where people actually shopped or ate. As new generation studies are beginning to show, most of the people do not shop for food in their immediate neighborhood.32, 33, 34 In epidemiological terms, mere proximity to a store is no longer a good index of exposure.

The Seattle Obesity Study (SOS) and the Residential Environment and Coronary Heart Disease (RECORD) studies are the only studies, to our knowledge, to include measures of the food environment at the individual level. In both studies, home addresses of study participants as well as the reported locations of their primary food stores were obtained and geocoded. The SOS and RECORD studies calculated distances to supermarkets that were the respondents’ primary food sources. Those procedures introduced, for the first time, the personalized dimension of individual food seeking behavior into the study of health and the built environment. Classifying supermarkets by food cost provided the needed additional measure of economic access to foods.32

Relatively little is known about the role of individualized food environment in relation to diet quality and body weight. The SOS and RECORD databases lent themselves to comparative analyses, given that similar data on SES and food environments were collected in both studies.32, 33, 35, 36 To our knowledge, no other study has collected data on SES variables, measures of food environment at the individual level, supermarket type and body weight.37

The present goal was to determine whether obesity rates in different cities are subject to shared socioeconomic and environmental pressures. Obesity rates in France are much lower than the reported rates in the United States.38, 39 Paris and Seattle are highly dissimilar in terms of urban landscape, residential density, walkability, public transport and ease of access to food stores.33 More critical perhaps is the fact that France and the United States differ greatly in their respective systems of disease prevention and health care. One important question is whether the socioeconomic and environmental determinants of body weight are limited to a specific urban context or are they, in fact, likely to be universal.40, 41, 42, 43

Methods and procedures

Population samples in SOS and RECORD studies

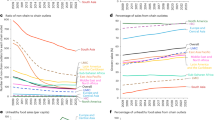

The SOS conducted in 2008–2009 was a population-based study of a sample of 2001 adult men and women, residing in King County, WA, USA.35 Detailed methodology has been published before.35, 36, 44 A stratified sampling scheme ensured adequate representation by income range and race/ethnicity. Randomly generated telephone numbers were matched with residential addresses using commercial databases. A pre-notification letter was mailed out to alert potential participants and telephone calls were placed in the afternoons and evenings by trained, computer-assisted interviewers with up to 13 follow-ups. An adult member of the household was randomly selected to be the survey respondent. Exclusion criteria were age <18 years, cell phone numbers and discordance between address data obtained from the vendor and self-reported by the respondent. The study protocol was approved by the UW Institutional Review Board. Analyses were based on 1304 respondents. The locations of SOS study households are indicated in Figure 1.

The RECORD study recruited 7290 participants between March 2007 and February 2008. The participants were affiliated with the French National Health Insurance System for Salaried Workers, which offers a free medical examination every 5 years to all working and retired employees and their families. People take part in preventive health checkups following referral of their family or workplace physician or on the advice of peers. RECORD participants were recruited among persons attending 2-h preventive checkups conducted by the Centre d’Investigations Préventives et Cliniques in four of its health centers located in Paris, Argenteuil, Trappes and Mantes-la-Jolie.45, 46, 47, 48 Eligibility criteria were: age 30–79 years; ability to complete study questionnaires; and residence in 1 of the 10 (out of 20) pre-selected administrative districts of Paris or in 111 other municipalities of the metropolitan area selected a priori. The pre-selection was intended to oversample disadvantaged municipalities and to allow for sufficient power to compare urban and suburban areas. Among potentially eligible respondents, based on age and residence, 10.9% were not selected because of linguistic or cognitive difficulties in filling out study questionnaires. Of the selected eligible persons, 83.6% accepted to participate and completed the entire data collection protocol for a total of 7131 respondents. The absence of a priori sampling of the participants resulted in selection mechanisms that were previously investigated.45 High educated participants and residents from high SES neighborhoods and low density neighborhoods had a higher likelihood of participation in the RECORD study.3

Both studies recruited participants from the city and its suburbs. In the SOS, the distinction was between the city of Seattle and the urban growth boundary of King County. In the RECORD study, the key distinction was between the 10 administrative districts in the city of Paris and the 111 municipalities of the Paris metropolitan area (banlieue, Figure 1).49

Demographic, socioeconomic, environmental and weight variables

Table 1 summarizes the principal variables used in the analyses of SOS and RECORD data. Both studies collected data on age, gender, education, incomes and household size. Educational attainment was recoded into three comparable categories for analytical purposes: high school or less, some college, and college graduates or higher. Annual household income was divided into tertiles. Questions about marital status and household size were the same in SOS and RECORD. The dichotomous variable living alone or not was computed based on the reported total number of household members in the SOS and was based on a question on cohabitation status in the RECORD study.

Heights and weights were obtained through telephone self-report in the SOS and measured by a nurse in RECORD study using a wall-mounted stadiometer and a calibrated scale (Seca, Paris, France).41 BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by square of height (m). The cutoff point for obesity (BMI>30 kg m−2) was the same in both studies.

Geocoding of home addresses

In the SOS, home addresses were geocoded to the centroid of the home parcel using the 2008 King County Assessor parcel data, and standard methods in ArcGIS 9.3.1 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA). Addresses that failed the automatic geocoding (30% using a 100% match score) were manually matched using a digital map environment, augmented by online resources such as GoogleMaps, QuestDEX and Yelp. Each home point was checked for plausibility and accuracy.

In the RECORD study, all home addresses were geocoded using the GeoLoc geocoding software of the French National of Statistics and Economic Studies, ensuring full compatibility with the Census data that are geocoded in the same way. Research assistants rectified incorrect or incomplete addresses with the participants by telephone and consulted with the Department of Urban Planning. Exact spatial coordinates and accurate block group codes were obtained for 100% of RECORD participants. Both sets of procedures were used to develop spatial coordinates that were used to calculate network distances between the home and the primary supermarket location.

Residential property values

Residential property values in SOS and in RECORD studies were based on buffers centered around each study participant’s residence. As such, residential property values represent personalized individual-level metrics that are respondent-centered and independent of any administrative neighborhood or area boundaries.

In the SOS, assessed residential property values were obtained from the 2008 King County tax assessor parcel database. Tax assessment in WA State estimates the full market value of a given property based on recent local sales data (King County Department of Assessments). Property values combined the value of land and improvements (buildings and other structures). These values were averaged within 833-m bandwidth of the individual respondent’s home to compute the neighborhood-property value metric. The detailed methodology has already been published.36 For parcels with multiple residential units such as apartment buildings, assessed value per unit was calculated as the sum of a parcel’s land and improvement values divided by the number of residential units on the parcel.

In the RECORD study, residential dwelling values were assessed on the basis of notary public data from 2003 to 2007 obtained from Paris-Notaires. After excluding sales with outlying values, prices of sales for each year were standardized on a 1–1000 scale to allow comparability across years and to provide an easier comparison with Seattle. Residential property values within a 500-m radius circular buffers centered on each participant’s residence were collected and mean price rank of dwellings sold between 2003 and 2007 in each buffer was then determined. The mean score was categorized by quartiles.

Primary supermarket characteristics

In the SOS, participants were asked to identify their primary food store along with its exact location. Individual full-service supermarkets were identified from the 2008 food establishment permits provided by Public Health Seattle and King County (PHSKC). They were defined as: stores run by nationally or regionally recognized chains, which engaged in retailing a broad selection of foods, such as canned and frozen foods; fresh fruits and vegetables; and fresh and prepared meats. The PHSKC data included 10 254 permit records, 926 of which belonged to 207 unique supermarket stores (most individual supermarkets had multiple permits); 99.6% of the permit addresses were geocoded by the Urban Form Lab (UFL), matched to King County parcel centroids, using ArcGIS, version 9.3.1 (ESRI).

In the RECORD study, participants were asked to report the brand name and street address of the supermarket where they did most of their food shopping.33 When the exact location of the primary supermarket could not be identified (for example, in cases of single streets with multiple supermarkets of the same brand), study participants were contacted in the month following their health examination to determine where exactly they shopped (790 participants were contacted). Technicians conducting these calls used Google Maps and the websites of the different supermarket brands to obtain the official business identification code (SIRET) of each supermarket. Out of 7290 participants, 7131 could be coded as conducting most of their food shopping in 1097 distinct supermarkets. Following previously published procedures, supermarkets were categorized as hard discount supermarkets, hypermarkets, small/large supermarkets, smaller city markets and organic food stores.33

Supermarket type by price

In the SOS and the RECORD study, supermarkets were classified into three strata by price. In the SOS, a market basket of 100 commonly consumed foods and beverages, adapted from the Consumer Price Index and Thrifty Food Plan Market Baskets, was developed. It was used to collect food prices from eight store brands: Safeway, Fred Meyer, Quality Food Centers (QFC), Puget Consumer Co-op (PCC), Albertsons, Trader Joe’s, Whole Foods and Metropolitan Market. The standardized methodology on the collection of food prices has been published before.50 Cluster analysis was used to categorize supermarkets into three price strata—low, medium and high.32, 51The lower cost stores included Fred Meyer, Winco Foods, Grocery Outlet and Albertson’s, Top Foods; medium cost included Safeway, QFC, Trader Joe’s and Red Apple Market; and higher cost included Whole Foods, Metropolitan Market, Madison Market and PCC Natural Markets.

In the RECORD study, supermarkets were classified into three strata by price according to the general knowledge of market segmentation and marketing strategies of the different types of stores. The lower cost stores were ‘hard discount’ supermarkets; medium-cost stores included large surfaces (hypermarkets) and small/large supermarkets; whereas higher-cost stores combined city markets (Monoprix, Franprix) and organic grocery stores.

Network distances to primary supermarket

Both SOS and RECORD studies calculated road network distances (km) from the home address to the supermarket that was reported to be the primary food source using ArcGIS 9.3.1 (ESRI). In SOS, street network data were obtained from ESRI StreetMap Premium and, in RECORD, from the National Geographic Institute.

Statistical analyses

Modified Poisson regression with robust error variance52 was conducted to examine the association between individualized food environment variables (proximity to the primary supermarket and supermarket-type by price), SES and obesity risk. Other covariates included age, gender, living alone or not, living inside the city or in the suburb, education, household income and neighborhood residential property values. All analyses were conducted using STATA, Statistical Software: Release 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Participant characteristics: SOS and RECORD

The characteristics of SOS and RECORD participants are shown in Table 2. The SOS sample was more likely to be female (63%), married (67%), college educated (57%) and >45 years old (74%). Annual household income was ⩾$50 K for 60% of the sample. For comparison, median income for King County was $53 157 based on 2000 census data. Obesity prevalence was 21%, similar to the county-wide estimate of 20.2%.

RECORD study participants were more likely to be male (65%), married (70%), and >45 years old (65%). Only 38% were college educated. Obesity prevalence was 12.4%, in line with the French national estimate of 12.4%. Pearson’s Chi Square tests indicated that the two samples were statistically comparable by most of the key sociodemographic variables, with the exception of gender and education (P-value <0.001 for each).

Participant characteristics by location of residence are also summarized in Table 2. Living in the city of Seattle, as opposed to living in the suburbs, was associated with higher education, living alone (39% vs 27%), shopping in more expensive supermarkets (20% vs 2%) and with lower obesity rates (18% vs 25%).

Living in the city of Paris, as opposed to living in the suburbs, was also associated with higher education, living alone (37% vs 27%), shopping in more expensive supermarkets (27% vs 12%) and with lower obesity rates (9% vs 14%).

Network distance to primary supermarkets: SOS and RECORD

The median distance between the participants’ homes and their primary supermarket was much smaller in Paris than in Seattle (Table 3). The median distance in central Paris was only 440 m as compared with 2.6 km in Seattle. The median distance to the primary supermarket in Paris suburbs was 1.41 km as compared with 3.64 km in Seattle suburbs. By supermarket-type by price, the distance to the higher-cost supermarkets was only 600 m in central Paris and 3.96 km in central Seattle. Paris suburbs also had better access to higher-cost supermarkets than did Seattle suburbs.

Table 4 shows that the sociodemographic profiles of supermarket shoppers were comparable across the two cities. Shoppers at higher-cost supermarkets in Seattle had higher education and incomes, whereas shoppers at lower-cost supermarkets had lower education and incomes. In Seattle, shoppers at low- and medium-cost supermarkets tended to be older and male, whereas shoppers at high-cost supermarkets tended to be younger and female. In the RECORD study, shoppers at high-cost supermarkets had higher education and incomes, with more pronounced effects observed for incomes.

In both Seattle and Paris, high-cost supermarket shoppers had significantly lower obesity rates. In Seattle, obesity prevalence among high-cost supermarket shoppers was only 8%, less than half of the King County average. By contrast, obesity prevalence among low-cost supermarket shoppers was 27%. In Paris, obesity prevalence among high-cost supermarket shoppers was only 7%, whereas among low-cost supermarket shoppers obesity rate was 16%.

Supermarket proximity and price: SOS and RECORD

Modified Poisson regression analyses examined the associations of obesity with food environment variables (supermarket proximity and price) and SES (Table 5).

Model 1 confirmed the inverse association between obesity and both individual SES (education and household income) and neighborhood-property values, adjusting for demographic variables and city limits. In both Seattle and Paris, higher education and higher household income were associated with lower obesity risk. In both the cities, higher residential property values were associated with a 40% lower obesity risk.

Model 2 introduced the two distinct supermarket variables: proximity and price. Obesity risk among shoppers at higher-cost supermarkets was reduced by 60% in Seattle and by 52% in Paris, relative to shoppers at lower-cost supermarkets, adjusting for individual- and neighborhood-level SES, demographic and distance variables. In both the cities, there was a graded inverse relationship between supermarket category by cost and obesity risk. No associations were observed between distance to the primary supermarket and obesity risk, either in Seattle or in Paris.

Discussion

The SOS and RECORD studies represent the first cross-city and cross-country comparison of the relative contribution of the individualized food environment variables and SES measures to obesity rates. As distinct from the neighborhood-based food environment, our individual-level measures of the food environment took into account actual food shopping destinations of the study respondents. Those included distance from home to the primary supermarket (a measure of physical access), as well as the price level of the primary supermarket used (a supermarket measure of economic access).

Analyses of the SOS and RECORD data showed that lower education and incomes in both Seattle and Paris were associated with higher obesity risk. Lower residential property values, an additional measure of SES reflecting wealth or the absence of wealth, were also associated with higher obesity risk. Finally, shopping at lower-cost supermarkets was associated with higher obesity risk in both the cities. Comparable findings of a significant SES gradient in obesity were obtained for the two cities and for the suburban areas.

By contrast, higher SES that was linked to living in more affluent neighborhoods and shopping at higher-cost supermarkets exerted a protective effect on obesity risk. Regression models showed that the social mechanisms underlying obesity rates in the two cities were remarkably similar. Some small differences were observed. In the Seattle, residential property values were a better predictor of obesity rates than either education or income. In some US-based studies, education was more protective for obesity than were incomes, suggesting that better education might be a way to reduce socioeconomic inequalities and improve health.53 In Paris, residential property values and education were closely linked.

The current distinction between physical and economic access to foods has relevance to the obesity-prevention strategies as adopted, respectively, by the United States and by France. First, physical distance to the primary supermarket had no impact on obesity rates either in Seattle or in Paris. These findings run counter to the general consensus in the United States that distance to the nearest supermarket is a predictor of both diet quality and body weight,19, 20, 24, 28, 54, 55, 56 especially in underserved areas.18, 20 Previous analyses of RECORD data reported only a very slightly higher BMI among participants shopping the furthest from their residence.33 On balance, these results suggest that distance to food stores, even when paired with presumably different travel modes57 (driving in Seattle and a mix of walking and driving in Paris) may have no direct influence on body weight.

By contrast, obesity rates varied sharply by supermarket type. Now, one popular assumption has been that all supermarkets offer healthful foods at an affordable cost.2, 19, 24, 54, 55, 58, 59, 60 However, not all supermarket chains offer food at the same low cost,20, 26, 61, 62, 63, 64 and it is well known that different chains cater to the different socioeconomic groups. One interpretation of the present data is that supermarket choice was an understudied manifestation of social class.36 Food-related attitudes and psychosocial factors are other variables that may influence the choice of the supermarket and foods purchased. Additional research will help determine what attitudinal, cultural or psychosocial variables, other than price, contributed to selecting one supermarket over another.

When it comes to policy, building new supermarkets in lower-income neighborhoods is thought to prevent obesity in the United States.20, 32 By contrast, US government reports have dismissed the issue of food prices as a potential contributing variable,65 suggesting that foods costs do not pose a barrier to the adoption of healthier diets, even by low income families on food receiving food assistance. Yet low income communities may be vulnerable to obesity not because the nearest supermarket is several kilometers away but because lower-cost foods tend to be energy dense but nutrient poor. In other words, access to food needs to be measured also in economic terms. In France, supermarket coverage is considered to be adequate. Both researchers and policymakers have focused on the quality of foods available in affluent vs deprived neighborhoods.

Both the SOS and RECORD studies had limitations. The SOS sample, based on a random landline-telephone survey (a standard BRFSS procedure) was older, better educated and had a higher proportion of females. Conversely, the Paris sample was largely male and had a lower proportion of college-educated respondents. BMI data were based on self-reported heights and weights in SOS. It is already known that the overweight or obese individuals tend to under-report their weight, which may have attenuated our results. However, the comparisons across Seattle and Paris would remain unaffected. In the SOS, classification of supermarkets by price was based on a direct assessment of a market basket of foods. The French classification was based on supermarket characteristics as described in the literature. The property values were computed using different spatial units (500 m buffer in Paris vs 833 m buffer in Seattle); however, these buffers sizes were determined based on the different urban form of the respective cities. Neighborhood-property values measured as buffers raised concerns for spatial clustering and correlation, although previous research using the SOS data set showed that there was no spatial clustering in the neighborhood-property value estimations.36, 66 Both studies were cross sectional, limiting our ability to draw causal inference from the observed associations.

Nonetheless, the present results underscored the importance of obtaining data on actual food shopping locations to complement objective information on the neighborhood-based food environment around the residence or workplace. Measuring the food environment at the individual level requires knowing who shops for food where, how often and why. Lacking such behavioral data, past studies were forced to assume, perhaps incorrectly, that most people shopped for food within their neighborhood. In the SOS, only 14% and, in the RECORD study, only 11.4% of the respondents shopped for food either at the closest supermarket or in their own residential neighborhood.33 It appears that people are willing to travel longer distances from home to arrive at the supermarket of their choice.

The present Seattle–Paris comparisons are valuable given the different socioeconomic, behavioral and environmental context of the two cities. The relative influences of income, education and property values on obesity rates in different countries can provide an insight into mechanisms that determine food choices, diet quality and selected health outcomes.67, 68, 69 Given the wide differences in urban form between Seattle and Paris, the present analyses attest to the potential generalizability of the socioeconomic determinants of weight and health.

The much higher prevalence of adult obesity in the United States as compared with France38, 39 can also be discussed in the context of very different social and medical systems dealing with disease prevention and health care. The present findings of a comparable SES gradient suggest that socioeconomic variables affect body weight even when the population has equal access to health care.

References

Frumkin H . Urban sprawl and public health. Public Health Rep 2002; 117: 201–217.

Rundle A, Neckerman KM, Freeman L, Lovasi GS, Purciel M, Quinn J et al. Neighborhood food environment and walkability predict obesity in New York City. Environ Health Perspect 2009; 117: 442–447.

Richard L, Gauvin L, Raine K . Ecological models revisited: their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annu Rev Public Health 2011; 32: 307–326.

Drewnowski A, Specter SE . Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79: 6–16.

Zhang Q, Wang Y . Trends in the association between obesity and socioeconomic status in U.S. adults: 1971 to 2000. Obes Res 2004; 12: 1622–1632.

Adler NE, Rehkopf DH . U.S. disparities in health: descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Public Health 2008; 29: 235–252.

McLaren L . Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev 2007; 29: 29–48.

Adler NE, Newman K . Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002; 21: 60–76.

Mendoza JA, Drewnowski A, Christakis DA . Dietary energy density is associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome in U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 974–979.

Drewnowski A, Darmon N . The economics of obesity: dietary energy density and energy cost. Am J Clin Nutr 2005; 82 (1 Suppl): 265S–273S.

Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Seymour JD, Tohill BC et al. Dietary energy density is associated with energy intake and weight status in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 83: 1362–1368.

Swinburn BA, Caterson I, Seidell JC, James WP . Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutr 2004; 7: 123–146.

Kant AK, Graubard BI . Energy density of diets reported by American adults: association with food group intake, nutrient intake, and body weight. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005; 29: 950–956.

Perrin AE, Simon C, Hedelin G, Arveiler D, Schaffer P, Schlienger JL . Ten-year trends of dietary intake in a middle-aged French population: relationship with educational level. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002; 56: 393–401.

Darmon N, Ferguson EL, Briend A . Impact of a cost constraint on nutritionally adequate food choices for French women: an analysis by linear programming. J Nutr Educ Behav 2006; 38: 82–90.

Méjean C, Macouillard P, Castetbon K, Kesse-Guyot E, Hercberg S . Socio-economic, demographic, lifestyle and health characteristics associated with consumption of fatty-sweetened and fatty-salted foods in middle-aged French adults. Br J Nutr 2011; 105: 776–786.

Bodor JN, Rice JC, Farley TA, Swalm CM, Rose D . The Association between obesity and urban food environments. J Urban Health 2010; 87: 771–781.

Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC . Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2009; 36: 74–81.

Morland K, Diez Roux AV, Wing S . Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity. Am J Prev Med 2006; 30: 333–339.

Treuhaft S, Karpyn A . The Grocery Gap: Who has access to healthy food and why it matters. Policy Link and The Food Trust: Oakland, CA, 2010.

Laska MN, Hearst MO, Forsyth A, Pasch KE, Lytle L . Neighbourhood food environments: are they associated with adolescent dietary intake, food purchases and weight status? Public Health Nutr 2010; 13: 1757–1763.

Ploeg MV . Access to Affordable, Nutritious Food is Limited in ‘Food Deserts’. USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

Gibson DM . The neighborhood food environment and adult weight status: estimates from longitudinal data. Am J Public Health 2011; 101: 71–78.

Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Nettleton JA, Jacobs DR Jr . Associations of the local food environment with diet quality—a comparison of assessments based on surveys and geographic information systems: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 167: 917–924.

Leal C, Bean K, Thomas F, Chaix B . Are associations between neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics and body mass index or waist circumference based on model extrapolations? Epidemiology 2011; 22: 694–703.

White M . Food access and obesity. Obes Rev 2007; 8: 99–107.

Larson N, Story M, Nelson M . Bringing Healthy Foods Home: Examining Inequalities in Access to Food Stores. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2008.

Michimi A, Wimberly MC . Associations of supermarket accessibility with obesity and fruit and vegetable consumption in the conterminous United States. Int J Health Geogr 2010; 9: 49.

Wang MC, Cubbin C, Ahn D, Winkleby MA . Changes in neighbourhood food store environment, food behaviour and body mass index, 1981–1990. Public Health Nutr 2008; 11: 963–970.

Leung CW, Laraia BA, Kelly M, Nickleach D, Adler NE, Kushi LH et al. The influence of neighborhood food stores on change in young girls' body mass index. Am J Prev Med 2011; 41: 43–51.

Charreire H, Casey R, Salze P, Simon C, Chaix B, Banos A et al. Measuring the food environment using geographical information systems: a methodological review. Public Health Nutr 2010; 13: 1773–1785.

Drewnowski A, Aggarwal A, Hurvitz PM, Monsivais P, Moudon AV . Obesity and supermarket access: proximity or price? Am J Public Health 2012; 102: e74–e80.

Chaix B, Bean K, Daniel M, Zenk SN, Kestens Y, Charreire H et al. Associations of supermarket characteristics with weight status and body fat: a multilevel analysis of individuals within supermarkets (RECORD study). PLoS One 2012; 7: e32908.

Boone-Heinonen J, Gordon-Larsen P, Kiefe CI, Shikany JM, Lewis CE, Popkin BM . Fast food restaurants and food stores: longitudinal associations with diet in young to middle-aged adults: the CARDIA study. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171: 1162–1170.

Aggarwal A, Monsivais P, Drewnowski A . Nutrient intakes linked to better health outcomes are associated with higher diet costs in the US. PloS One 2012; 7: e37533.

Moudon AV, Cook AJ, Ulmer J, Hurvitz PM, Drewnowski A . A neighborhood wealth metric for use in health studies. Am J Prev Med 2011; 41: 88–97.

White M . Food access and obesity. Obes Rev 2007; 8 (Suppl 1): 99–107.

Charles MA, Eschwege E, Basdevant A . Monitoring the obesity epidemic in France: the Obepi surveys 1997–2006. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008; 16: 2182–2186.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL . Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA 2012; 307: 491–497.

Turrell G, Hewitt B, Patterson C, Oldenburg B . Measuring socio-economic position in dietary research: is choice of socio-economic indicator important? Public Health Nutr 2003; 6: 191–200.

Thomas F, Bean K, Pannier B, Oppert JM, Guize L, Benetos A . Cardiovascular mortality in overweight subjects: the key role of associated risk factors. Hypertension 2005; 46: 654–659.

Wang MC, Kim S, Gonzalez AA, MacLeod KE, Winkleby MA . Socioeconomic and food-related physical characteristics of the neighbourhood environment are associated with body mass index. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007; 61: 491–498.

Friel S, Marmot MG . Action on the social determinants of health and health inequities goes global. Annu Rev Public Health 2011; 32: 225–236.

Aggarwal A, Monsivais P, Cook AJ, Drewnowski A . Does diet cost mediate the relation between socioeconomic position and diet quality? Eur J Clin Nutr 2011; 65: 1059–1066.

Chaix B, Leal C, Evans D . Neighborhood-level confounding in epidemiologic studies: unavoidable challenges, uncertain solutions. Epidemiology 2011; 21: 124–127.

Chaix B, Kestens Y, Bean K, Leal C, Karusisi N, Meghiref K et al. Cohort profile: residential and non-residential environments, individual activity spaces and cardiovascular risk factors and diseases—The RECORD Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol 2011; 41: 1283–1292.

Chaix B, Jouven X, Thomas F, Leal C, Billaudeau N, Bean K et al. Why socially deprived populations have a faster resting heart rate: impact of behaviour, life course anthropometry, and biology—the RECORD Cohort Study. Soc Sci Med 2011; 73: 1543–1550.

Chaix B, Bean K, Leal C, Thomas F, Havard S, Evans D et al. Individual/neighborhood social factors and blood pressure in the RECORD Cohort Study: which risk factors explain the associations? Hypertension 2010; 55: 769–775.

Charreire H, Weber C, Chaix B, Salze P, Casey R, Banos A et al. Identifying built environmental patterns using cluster analysis and GIS: relationships with walking, cycling and body mass index in French adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity 2012; 9: 59.

Monsivais P, Drewnowski A . The rising cost of low-energy-density foods. J Am Diet Assoc 2007; 107: 2071–2076.

Mahmud NK, Monsivais P, Drewnowski A . The Search for Affordable Nutrient Rich Foods: A Comparison of Supermarket Food Prices in Seattle-King County. Center for Public Health Nutrition, University of Washington, 2009.

Zou G . A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 159: 702–706.

Devaux M, Sassi F . Social inequalities in obesity and overweight in 11 OECD countries. Eur J Public Health 2011; 23: 464–469.

Powell LM, Auld MC, Chaloupka FJ, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD . Associations between access to food stores and adolescent body mass index. Am J Prev Med 2007; 33: S301–S307.

Morland K, Wing S, Roux AD . The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Public Health 2002; 92: 1761–1767.

Morland KB, Evenson KR . Obesity prevalence and the local food environment. Health Place 2009; 15: 491–495.

Jiao J, Moudon A, Drewnowski A . Grocery Shopping. Transportation Res Rec 2011; 2230: 85–95.

Kaufman P . Rural poor have less access to supermarkets, larger grocery stores. Rural Dev Perspect 1999; 13: 19–26.

Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, James SA, Bao S, Wilson ML . Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. Am J Public Health 2005; 95: 660–667.

Franco M, Diez Roux AV, Glass TA, Caballero B, Brancati FL . Neighborhood characteristics and availability of healthy foods in Baltimore. Am J Prev Med 2008; 35: 561–567.

Chung C, Myers S . Do the poor pay more for food? An analysis of grocery store availability and food price disparities. J Consumer Aff 1999; 33: 276–296.

MacDonald JM . Do the poor still pay more? Food price variations in large metropolitan areas. J Urban Econ 1991; 30: 344–359.

White M, Bunting J, Williams L, Raybould S, Adamson A, Mathers J . Do Food Deserts Exist? A Multilevel Geographical Analysis of the Relationship Between Retail Food Access, Socioeconomic Position and Dietary Intake. University of Newcastle, 2002.

Jiao J, Moudon AV, Ulmer J, Hurvitz PM, Drewnowski A . How to identify food deserts: measuring physical and economic access to supermarkets in King County, Washington. Am J Public Health 2012; 102: e32–e39.

Carlson A, Frazao E Are healthy foods really more expensive? It depends on how you measure the price, EIB-96. In: Agriculture UDo, (ed): Economic Research Service: Washington, DC 2012.

Caspi CE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Adamkiewicz G, Sorensen G . The relationship between diet and perceived and objective access to supermarkets among low-income housing residents. Soc Sci Med 2012; 75: 1254–1262.

Drewnowski A, Fiddler EC, Dauchet L, Galan P, Hercberg S . Diet quality measures and cardiovascular risk factors in France: applying the Healthy Eating Index to the SU.VI.MAX study. J Am Coll Nutr 2009; 28: 22–29.

Rozin P, Fischler C, Shields C, Masson E . Attitudes towards large numbers of choices in the food domain: a cross-cultural study of five countries in Europe and the USA. Appetite 2006; 46: 304–308.

Rozin P, Remick AK, Fischler C . Broad themes of difference between French and Americans in attitudes to food and other life domains: personal versus communal values, quantity versus quality, and comforts versus joys. Front Psychol 2011; 2: 177.

Acknowledgements

The Seattle Obesity Study (SOS) was supported by NIH Grant R01DK076608 on food environment and disparities in obesity and by NIH Grant R21 DK085406. The RECORD study in Paris was supported by l’Institut de Recherche en Santé Publique (IReSP), l’Institut National de Prévention et d’Education à la Santé (INPES), l’Institut de Veille Sanitaire (InVS), les Ministères de la Santé et de la Recherche, l’Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), le Groupement Régional de Santé Publique (GRSP) d’Île-de-France, la Direction Régionale des Affaires Sanitaires et Sociales d’Île-de-France (DRASSIF), la Direction Régionale de la Jeunesse et des Sports d’Île-de-France (DRDJS) and le Conseil Régional d’Île358 de-France and by l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Santé Publique (EHESP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Drewnowski, A., Moudon, A., Jiao, J. et al. Food environment and socioeconomic status influence obesity rates in Seattle and in Paris. Int J Obes 38, 306–314 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.97

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.97

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Human spatial memory is biased towards high-calorie foods: a cross-cultural online experiment

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (2022)

-

The Associations Between Urban Form and Major Non-communicable Diseases: a Systematic Review

Journal of Urban Health (2022)

-

Ultra-processed foods and obesity and adiposity parameters among children and adolescents: a systematic review

European Journal of Nutrition (2022)

-

The retail food environment and its association with body mass index in Mexico

International Journal of Obesity (2021)

-

Relationship between psychological stress and metabolism in morbidly obese individuals

Wiener klinische Wochenschrift (2020)