Abstract

Introduction:

Cholelithiasis is increasingly encountered in childhood and adolescence due to the rise in obesity. As in adults, weight loss is presumed to be an important risk factor for cholelithiasis in children, but this has not been studied.

Methods:

In a prospective observational cohort study we evaluated the presence of gallstones in 288 severely obese children and adolescents (mean age 14.1±2.4 years, body mass index (BMI) z-score 3.39±0.37) before and after participating in a 6-month lifestyle intervention program.

Results:

During the lifestyle intervention, 17/288 children (5.9%) developed gallstones. Gallstones were only observed in those losing >10% of initial body weight and the prevalence was highest in those losing >25% of weight. In multivariate analysis change in BMI z-score (odds ratio (OR) 3.26 (per 0.5 s.d. decrease); 95% CI:1.60–6.65) and baseline BMI z-score (OR 2.32 (per 0.5 s.d.); 95% CI: 1.16–4.70) were independently correlated with the development of gallstones. Sex, family history, OAC use, puberty and biochemistry were not predictive in this cohort. During post-treatment follow-up (range 0.4–7.8 years) cholecystectomy was performed in 22% of those with cholelithiasis. No serious complications due to gallstones occurred.

Conclusion:

The risk of developing gallstones in obese children and adolescents during a lifestyle intervention is limited and mainly related to the degree of weight loss and initial body weight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The reported prevalence of gallstones in children and adolescents range from 0.13% in the general population studies to 1.9% in hospital-based studies.1,2 As in adults, obesity has been established as an important risk factor for cholelithiasis in children (8–19 years old).3, 4, 5 Recently, two large studies have reported an increased prevalence of symptomatic gallstone disease related to the increased prevalence of obesity in the last two decades.4,6 Female sex, use of oral anticonceptives, older age and Hispanic descent have been identified as additional risk factors in children.4 However, no studies are available regarding the risks related to weight loss and lifestyle interventions in children. In this study we aimed to (1) evaluate the risk for development of gallstones in children participating in a lifestyle intervention and (2) assess the long-term rate of complications due to gallstones in these children.

Subjects and methods

Population

In a prospective observational cohort study all children and adolescents participating in a Dutch tertiary centre-based lifestyle intervention program (Heideheuvel Childhood Obesity Centre) between November 2004 and April 2012 were evaluated for inclusion. Inclusion criteria for the lifestyle program were age range of 8–18 years and severe primary obesity (body mass index adjusted for age (BMI-for-age) >35 kg m−2) or primary obesity (BMI-for-age >30 kg m−2) with obesity-related co-morbidity. Exclusion criteria for this study were haemolytic disorders, previous small bowel resection, use of parenteral nutrition, Crohn’s disease, cystic fibrosis, cholecystectomy or no ultrasonography at baseline. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Centre of the University of Amsterdam and VU University Medical Centre.

Intervention

The lifestyle program consisted of scheduled exercise, promotion of self-initiated physical activities, nutrition modification therapy and behaviour modification during 6 months. Nutrition modification was given using a non-diet approach and focused on the quality of the dietary intake and eating behaviour. Behaviour modification therapy consisted of coping skills training focused on self-regulation, self-awareness, goal setting and stimulus control. Children attended the 6-month treatment period in either an outpatient setting consisting of 12 days of treatment with homework assignments, an inpatient program of 2 months followed by biweekly return visits for 4 months or treatment in an inpatient setting for 6 months. Children were allocated to either setting based on the availability and patients’ preference.

Measurements

All measurements (ultrasonography, laboratory tests and physical examination) were obtained at the start of the lifestyle intervention program and were repeated at the end of the 6-months treatment period.

History taking and physical examination were performed by experienced pediatricians in the obesity clinic. Weight and height were measured to calculate the age-adjusted BMI standard deviation score, the BMI z-score. The pubertal stages were determined by visual inspection using Tanner’s criteria.

Blood was drawn after an overnight fast and measurements included lipid spectrum, liver function tests, glucose and insulin. Insulin sensitivity was calculated using the ‘Homeostasis Model Assessment of insulin resistance’ formula (HOMA-IR).7 Ultrasonography was performed by one of three experienced radiologists blinded for the clinical data in an adjacent local hospital.

Long-term follow-up

Participants with gallstones, both at baseline and those who developed gallstones during the lifestyle program, were contacted in February 2013 by telephone. Using a questionnaire, symptoms (nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting and right upper quadrant abdominal pain), complications (choledocholithiasis, pancreatitis and cholecystitis) and treatment (cholecystectomy) related to gallstone disease were retrospectively evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Standard descriptive statistics were used. Logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors predictive of gallstone development during lifestyle intervention. All parameters with P<0.10 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate regression analyses. To prevent overfitting, parameters were combined using forward selection. Effect modification for sex and age on the selected parameters was studied and added to the model if P<0.10. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Between November 2004 and April 2012, 407 children participated in the lifestyle intervention program. Twenty-six children were excluded because ultrasonography at baseline was either not obtained or was unsuccessful. The prevalence of gallstones at baseline was 14/381 (3.6%). After inclusion, 93 additional children could not be analysed for the development of gallstones during the lifestyle intervention, because gallstones were already present at baseline (n=14) or ultrasonography was not performed at 6 months (n=79). Thus, 288 children completed the study protocol. The 79 children who had no ultrasonography at 6 months were not significantly different for any of the baseline characteristics. All children with gallstones, either present at baseline or developed during the program, were included in the long-term follow-up for complications.

Table 1 depicts the characteristics of the 288 participants who completed the protocol, both at baseline and at the end of the lifestyle program. Mean weight loss was 11.9±9.9 kg (10.4% of mean body weight). After the 6-month lifestyle intervention program 17 out of 288 children (5.9%) had developed gallstones.

In univariate analyses for the baseline parameters, severity of obesity correlated with the development of gallstones during the lifestyle intervention (Table 2). No correlations with sex, ethnicity, family history, oral anticonceptive use, puberty or biochemistry at baseline were observed.

Evaluating the change in BMI and change in biochemical parameters during the lifestyle intervention program, improvement in BMI z-score was univariately correlated with a higher risk for developing gallstones (Table 2). Decrease in total cholesterol was the only biochemical parameter correlating with the development of gallstones.

In multivariate analysis change in BMI z-score (OR 3.26 (per 0.5 s.d. decrease); 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.60–6.65; P=0.001) and baseline BMI z-score (OR 2.32 (per 0.5 s.d. increase); 95% CI: 1.16–4.70; P=0.018) were independently correlated with the development of gallstones. Decrease in total cholesterol was not independently correlated when combined with change in BMI z-score. No collinearity between BMI z-score and change in BMI z-score was observed (Pearson’s correlation coefficient 0.054). There was no confounding or effect modification between these two parameters. No effect modification by gender or age was observed.

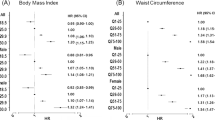

As shown in Figure 1, none of the patients losing <10% of initial weight developed gallstones. The risk for the development of gallstones was the highest when losing >25% of initial weight (P=0.028).

Long-term follow-up

The 31 children and adolescents who had gallstones at baseline (n=14) or developed gallstones during treatment (n=17) were contacted by telephone in February 2013. Seven patients could not be traced and one refused to participate. The mean duration of follow-up of the 23 participants interviewed was 4.8 years (range 0.4–7.8 years).

Twelve children experienced transient symptoms possibly related to gallstone disease (nausea and dyspepsia). Seven children reported episodic colic pain in right upper abdomen without jaundice or pruritis (three children with gallstones at baseline and four who developed gallstones during lifestyle program). Cholecystectomy because of colic complaints was performed in five children (two children with gallstones at baseline and three with gallstones developed during the program), with subsequent disappearance of symptoms. None of the participants reported serious complications due to cholelithiasis.

Discussion

This study is the first pediatric study prospectively analysing the risk factors for developing gallstones during a lifestyle intervention program. In this study, 5.9% of children developed gallstones during treatment. Although 5.9% can be considered a small risk, comparison to the baseline prevalence of gallstones in this study (3.6%) shows that weight loss substantially increases the chances for developing gallstones in these children. The degree of weight loss and severity of obesity at baseline were the only variables related with the risk of developing gallstones. Sex, family history for gallstones, oral anticonceptive use, puberty and biochemistry were not predictive in this cohort. Gallstones were only observed in children losing >10% of initial body weight and the prevalence was highest in those losing >25% of weight.

Several studies have shown that obesity and severity of obesity are risk factors for gallstones in children.3, 4, 5, 6 Although some studies included the number of reported previous weight loss attempt in their analysis, these transversal studies are unfit to accurately determine the risk for developing gallstones during a lifestyle intervention.3

In adults, the risk of gallstones development during obesity treatment has been studied prospectively, but mainly for very-low-calorie diets and bariatric surgery. The reported prevalence of the development of gallstones reaches 12% in adults during very-low-calorie diets and up to 30% in patients after bariatric surgery.8,9 One of the largest adult studies on very-low-calorie diets identified risk factors (higher initial BMI, higher relative BMI loss and higher initial triglycerides), which overlap with those observed in our cohort.10 This study, similar to our study, showed no gender difference in the risk for developing gallstones. A higher risk in females has been reported in smaller and transversal adult studies.8 In both our and this very-low-calorie diet study, other established risk factors for gallstones (oral anticonceptive use, older age and a positive family history) did not correlate with the risk for gallstones during a lifestyle intervention.10 In line with our study, the largest bariatric surgery study in obese adults (n=586) showed that losing >25% of initial weight was the only prognostic feature for the development of symptomatic gallstones after bariatric surgery.11 Age, gender and baseline BMI did not correlate with the development of gallstones in this study.

Speed of weight loss is considered an additional risk factor for gallstones.8 This is underscored by a recent study showing more symptomatic gallstones in those using a very-low-calorie versus a low-calorie diet.12 In our study no data on the speed of weight loss were available; therefore, this could not be analysed as a risk factor.

During the median 5-year follow-up of the children with gallstones, possible gallstone-related symptoms were reported in 52% of the responding patients. Cholecystectomy for colic complaints was performed in 22% of patients with gallstones. In a retrospective cohort study of all children diagnosed with gallstones in a hospital setting, comparable percentages were reported: symptomatic gallstones disease in 49% and cholecystectomy in 32% during a median 3-year follow-up.13 Even though numbers are small, based on the absence of serious complications in our cohort a conservative management seems warranted in gallstones related to obesity and lifestyle interventions.

A limitation of this study is that few cases of gallstones were observed. Therefore, only the strongest correlating parameters could be identified. Another limitation is the high number of included children that could not be analysed due to dropout during the program. However, this is a limitation of most longitudinal studies in obesity.14 The high dropout in our study is not likely to have influenced the study results, as this group was at baseline not significantly different from those who completed the study. Finally, the accuracy of the follow-up data is disputable as the duration of follow-up was limited and it was analysed retrospectively with no follow-up results in 25% of patients.

Conclusion

The incidence of gallstones in obese children and adolescents during a lifestyle intervention is 5.9%. This is strongly related to the severity of obesity and the degree of weight loss. Only patients with >10% weight loss compared with their initial weight developed gallstones in our study. Follow-up data suggest that serious complications of gallstones occur infrequently, although cholecystectomy is performed in up to 22% of the children.

References

Palasciano G, Portincasa P, Vinciguerra V, Velardi A, Tardi S, Baldassarre G et al. Gallstone prevalence and gallbladder volume in children and adolescents: an epidemiological ultrasonographic survey and relationship to body mass index. Am J Gastroenterol 1989; 84: 1378–1382.

Wesdorp I, Bosman D, de Graaff A, Aronson D, van der Blij F, Taminiau J . Clinical presentations and predisposing factors of cholelithiasis and sludge in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000; 31: 411–417.

Kaechele V, Wabitsch M, Thiere D, Kessler AL, Haenle MM, Mayer H et al. Prevalence of gallbladder stone disease in obese children and adolescents: influence of the degree of obesity, sex, and pubertal development. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006; 42: 66–70.

Koebnick C, Smith N, Black MH, Porter AH, Richie BA, Hudson S et al. Pediatric obesity and gallstone disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 55: 328–333.

Mehta S, Lopez ME, Chumpitazi BP, Mazziotti MV, Brandt ML, Fishman DS . Clinical characteristics and risk factors for symptomatic pediatric gallbladder disease. Pediatrics 2012; 129: e82–e88.

Fradin K, Racine AD, Belamarich PF . Obesity and symptomatic cholelithiasis in childhood: epidemiologic and case-control evidence for a strong relationship. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 58: 102–106.

Keskin M, Kurtoglu S, Kendirci M, Atabek ME, Yazici C . Homeostasis model assessment is more reliable than the fasting glucose/insulin ratio and quantitative insulin sensitivity check index for assessing insulin resistance among obese children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2005; 115: e500–e503.

Everhart JE . Contributions of obesity and weight loss to gallstone disease. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119: 1029–1035.

Erlinger S . Gallstones in obesity and weight loss. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 12: 1347–1352.

Yang H, Petersen GM, Roth MP, Schoenfield LJ, Marks JW . Risk factors for gallstone formation during rapid loss of weight. Dig Dis Sci 1992; 37: 912–918.

Li VK, Pulido N, Fajnwaks P, Szomstein S, Rosenthal R, Martinez-Duartez P . Predictors of gallstone formation after bariatric surgery: a multivariate analysis of risk factors comparing gastric bypass, gastric banding, and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 2009; 23: 1640–1644.

Johansson K, Sundström J, Marcus C, Hemmingsson E, Neovius M . Risk of symptomatic gallstones and cholecystectomy after a very-low-calorie diet or low-calorie diet in a commercial weight loss program: 1-year matched cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014; 38: 279–284.

Bogue CO, Murphy AJ, Gerstle JT, Moineddin R, Daneman A . Risk factors, complications, and outcomes of gallstones in children: a single-center review. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010; 50: 303–308.

Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, Shrewsbury VA, O’Malley C, Stolk RP et al. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; CD001872.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the pediatricians at Heideheuvel Childhood Obesity Centre for recruiting patients, the CBSL laboratory of the Ter Gooi Hospital for helping in collecting and storing samples. This work was supported by grants from Het Innovatiefonds Zorgverzekeraars (Zeist, The Netherlands) and Van den Broek Lohman Foundation Nunspeet (Nunspeet, The Netherlands).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Heida, A., Koot, B., vd Baan-Slootweg, O. et al. Gallstone disease in severely obese children participating in a lifestyle intervention program: incidence and risk factors. Int J Obes 38, 950–953 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.12

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.12

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Pediatric biliary calculus disease: clinical spectrum, predisposing factors, and management outcome revisited

Annals of Pediatric Surgery (2022)

-

Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of pediatric obesity: consensus position statement of the Italian Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology and the Italian Society of Pediatrics

Italian Journal of Pediatrics (2018)