Abstract

Background/Objective:

Fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) and 21 (FGF21) have been linked to obesity and type 2 diabetes in adults. We assessed the circulating concentrations of these factors in human neonates and infants, and their association with the endocrine–metabolic changes associated to prenatal growth restraint.

Subjects/Methods:

Circulating FGF19 and FGF21, selected hormones (insulin, insulin-like growth factor I and high- molecular-weight (HMW) adiponectin) and body composition (absorptiometry) were assessed longitudinally in 44 infants born appropriate- (AGA) or small-for-gestational-age (SGA). Measurements were performed at 0, 4 and 12 months in AGA infants; at 0 and 4 months in SGA infants; and cross-sectionally in 11 first-week AGA newborns.

Results:

Circulating FGF19 and FGF21 surged >10-fold in early infancy from infra- to supra-adult concentrations, the FGF19 surge appearing slower and more pronounced than the FGF21 surge. Whereas the FGF21 surge was of similar magnitude in AGA and SGA infants, FGF19 induction was significantly reduced in SGA infants. In AGA and SGA infants, cord-blood FGF21 and serum FGF19 at 4 months showed a positive correlation with HMW adiponectin (r=0.49, P=0.013; r=0.43, P=0.019, respectively).

Conclusions:

Our results suggest that these early FGF19 and FGF21 surges are of a physiological relevance that warrants further delineation and that may extend beyond infancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

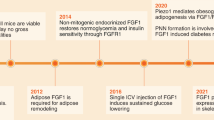

Some fibroblast growth factor family proteins are known to function in an endocrine manner and to be involved in metabolic processes related to energy balance.1, 2, 3, 4 Fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) is secreted mainly by the ileum and its primary role is the control of the hepatic biosynthesis of bile acids,5 although metabolic effects reminiscent of insulin actions have also been reported.6 In contrast, fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is a new metabolic regulator of noninsulin-dependent glucose transport in cells,7 and is mainly expressed and released by the liver8 in response to increased fatty acid availability.9 These biological effects have put forward FGF21 as a potential candidate in the treatment of type 2 diabetes, obesity and the metabolic syndrome.10

Both FGF19 and FGF21 act on target cells through cell surface FGF receptors interacting specifically with the coreceptor beta-Klotho. These factors can modulate glucose and lipid metabolism in response to nutritional status, and improve glucose uptake in adipocytes in vitro.11 Administration of FGF19 or FGF21 reduces body weight and glucose levels in obese and diabetic mice and primates.11, 12 In addition, both factors can normalize triglyceride levels, increasing energy expenditure and improving insulin sensitivity.1, 13, 14

Interestingly, obese- and insulin-resistant patients have decreased levels of FGF19,15, 16 and obese patients who show remission of diabetes after a gastric bypass display the highest increase in FGF19.17 Paradoxically, high levels of FGF21 have been reported in obesity, metabolic syndromes, type 2 diabetes and coronary diseases in human studies.18 In those studies, circulating FGF21 associated positively with body mass index, glucose and measures of insulin resistance in adults;16, 19, 20 however, these associations have not been consistently reported in children.21, 22, 23

Major metabolic changes occur rapidly in the transition from fetal life—characterized by the predominant utilization of glucose as metabolic fuel—to postnatal life, where the use of lipids from milk prevails.24 The perinatal environment can affect glucose homeostasis and influence the risk for obesity and type 2 diabetes.25 Human infants born small-for-gestational-age (SGA) who experience spontaneous postnatal catch-up in weight have a higher risk to develop metabolic abnormalities.26, 27 For example, the association of rapid weight gain with increased adiposity and obesity in later life in infants born small has been established in several studies.28

Here we hypothesized that FGF19 and FGF21 could be among the factors modulating metabolic adaptations in early life. To address this hypothesis, we evaluated the developmental changes of these endocrine factors in human infants, and longitudinally assessed the serum levels of FGF19 and FGF21 in healthy term SGA and appropriate-for-gestational-age (AGA) newborns.

Materials and methods

Study population

The study population consisted of n=44 term infants (22 AGA and 22 SGA) selected (see flow chart in Figure 1) from among those participating in a longitudinal study that assesses the body composition and endocrine–metabolic state of SGA infants, as compared with the AGA controls, in the first postnatal years.29, 30, 31

The present study included only those infants in whom the remaining serum sample was sufficiently abundant to measure FGF19 and FGF21 and who had, in addition, longitudinal clinical, biochemical and body composition data. The study was focused on: (a) evaluation of the early induction of FGF19 and FGF21 throughout the first year of life in AGA newborns; (b) comparison of FGF19 and FGF21 levels in AGA vs SGA infants at birth and at age 4 months.

As described,29, 30 the inclusion criteria were:

-

uncomplicated, term pregnancy (no gestational diabetes; no preeclampsia; no alcohol or drug abuse) with delivery at Hospital Sant Joan de Déu in Barcelona

-

birth weight between −1 s.d. and +1 s.d. for gestational age in AGA newborns and below −2 s.d. for SGA newborns31

-

exclusive breastfeeding during the first 4 months of life

-

written, informed consent in Spanish/Catalan language

Exclusion criteria were twin pregnancies, complications at birth and congenital malformations.

In order to elucidate the timing of the induction of FGF19 and FGF21 in newborns and the impact of milk intake, the circulating levels of these two factors were also measured in 11 AGA newborns (mean postnatal age 35 h, range 10–77 h; Figure 1). These newborns were recruited at the hospital nursery at the time of blood sampling for standard screening of bilirubinemia or metabolic diseases.

All assessments were performed in the fasting state (that is, immediately before the first morning feeding), after approval by the Institutional Review Board of Barcelona University, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, and after written informed consent by the newborn’s mother and/or father.

Serum FGF19 and FGF21 were also measured in a cohort of 35 healthy, nonobese volunteers (mean age 43 years; body mass index 24.5±0.5 kg m−2, 77% males) recruited at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain) into an additional study assessing circulating adipokines and body adiposity in adults (described in Gallego-Escuredo et al.16). These values were compared to those of AGA and SGA newborns throughout the follow-up.

Assessments

Insulin, glucose and insulin-like growth factor I were measured by immunochemiluminescence, as described.31 Insulin resistance was estimated from fasting insulin and glucose levels with the homeostatic model assessment: homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance=(fasting insulin (mU l−1)) × (fasting glucose (mmol l−1))/22.5.32 HMW adiponectin was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Linco Research, St Charles, MO, USA) with intra- and inter-assay CVs <9%.

Circulating FGF19 and FGF21 levels were determined using non-cross-reactive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays specific for the corresponding human proteins (Biovendor, Brno, Czech Republic). The detection limits for the FGF19 and FGF21 assays were 7.0 and 4.8 pg ml−1, respectively. The intra-assay coefficients of variations (CVs) were 6% for FGF19 and 3.5% for FGF21; the interassay CVs were 7.5% for FGF19 and 3.7% for FGF21, respectively.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 (IBM SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Results are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Differences between specific groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test (two-tailed) for comparisons between the two groups. Univariate associations of FGF19 and FGF21 with the endocrine–metabolic parameters were tested by Spearman correlation followed by multiple regression analyses in a stepwise manner; P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were normally distributed (as verified by D'Agostino–Pearson omnibus normality test and verified by means of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), except for FGF21. Accordingly, FGF21 data were log transformed for statistical analyses, as described.16, 33

Results

Table 1 summarizes the main clinical, body composition and endocrine–metabolic variables; some of these data have been previously reported in part (30%) of the studied population.29, 30

The percentage of caesarian sections was similar in the AGA and SGA subgroups (23% vs 27%).

Longitudinal changes in FGF19 and FGF21 in AGA infants

FGF19 and FGF21 were similar in boys and girls, and thus, the results were pooled.

FGF19 concentrations (mean±s.e.m.) were low in cord blood (24.0±6.9 pg ml−1), remained low in the first week of life (32.9±19 pg ml−1), experienced a dramatic increase at the age of 4 months (614.8±70.7 pg ml−1; P<0.0001 vs 0 months) well above adult levels, and decreased significantly at the age of 12 months (314.5±61.8 pg ml−1; P<0.001 vs 4 months) within the range of adult concentrations (Figure 2a).

Developmental changes in circulating FGF19 and FGF21 in human infants. AGA, appropriate-for-gestational-age; SGA, small-for-gestational-age. Values are mean±s.e.m. In AGA newborns, FGF19 levels were assessed at birth (day 0; n=14); at day 2 (≈35 h of life; n=11); at 4 months (n=15); and at 12 months (n=11). FGF21 levels were assessed at birth (day 0; n=21); at day 2 (≈35 h of life; n=11); at 4 months (n=20); and at 12 months (n=17). In SGA newborns, FGF19 levels were assessed at birth (day 0; n=14) and at 4 months (n=14). FGF21 levels were assessed at birth (day 0; n=21) and at 4 months (n=19). The line and dashed bars are the mean±s.e.m. of adult levels (n=35; see text for details). (a) Serum FGF19 and FGF21 levels in AGA infants from birth to age 12 months. For FGF19, *P=0.0001 (0 vs 4 months and 0 vs 12 months); †P=0.005 (4 vs 12 months); #P=0.0001 (0, 2 days and 4 months vs adults). For FGF21, *P=0.0001 (0 vs 2 days); **P=0.0003 (0 vs 4 months); ***P=0.009 (0 vs 12 months); #P=0.02 (0 vs adults); ##P=0.008 (4 months vs adults); ###P=0.01 (12 months vs adults). (b) Serum FGF19 and FGF21 levels in AGA (black circles) and SGA infants (white circles) at birth and at the age of 4 months. For FGF19, #P=0.0001 (0 vs 4 in the AGA subgroup); †P=0.0001(0 vs 4 months in the SGA subgroup); *P=0.0001 (AGA vs SGA at 4 months). For FGF21, #P=0.0001 (0 vs 4 in the AGA subgroup); †P=0.0001(0 vs 4 in the SGA subgroup).

FGF21 was also low in cord blood (mean±s.e.m., 42.8±3.9 pg ml−1), increased significantly in the first week of life (211.2±54.1 pg ml−1; P<0.0001), and showed no significant variations over the first 12 months (307.1±67.9 and 448.9±175.6 pg ml−1 at 4 months and at 12 months, respectively), reaching concentrations that were ~1.4-fold higher (P=0.01) than those in adults (Figure 2a).

Longitudinal changes in FGF19 and FGF21 in AGA vs SGA newborns

Serum concentrations of FGF19 in SGA newborns were not significantly different from those in AGA newborns at birth (mean±s.e.m., 49.8±19.0 pg ml−1); at the age of 4 months, SGA infants had significantly lower levels of circulating FGF19 than AGA infants (302.4±50.5 vs 614.8±70.7 pg ml−1; P<0.0001). Serum FGF21 levels were in SGA infants similar to those in AGA infants at birth and at 4 months (43.2±7.9 and 260.1±45.0 pg ml−1, respectively) (Figure 1b).

The mode of delivery had no influence on longitudinal FGF19 and FGF21 levels.

Correlations

In both AGA and SGA infants, FGF19 correlated positively with HMW adiponectin (r=0.43; P=0.019) at the age of 4 months, independent of body mass index and gender. Cord blood FGF21 correlated positively with HMW adiponectin in both AGA and SGA infants (r=0.49; P=0.013). At the age of 4 months, FGF21 correlated positively with the ponderal index in AGA and SGA infants (r=0.36; P=0.02), and inversely with fasting insulin and homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (r=−0.59; P=0.009 in both) only in SGA infants. These associations were independent from gestational age, gender and mode of delivery.

Discussion

Here we report for the first time the early induction of FGF19 and FGF21 throughout the first year of postnatal life in term, breastfed, AGA human newborns, and describe the longitudinal changes of FGF19 and FGF21 in AGA and SGA infants at birth and at the age of 4 months. The limitations of the study are the relatively small sample size and the lack of follow-up beyond 4 months in the AGA vs SGA comparisons; these limitations were mostly due to the fact that the study population was composed of healthy infants, and that fasting blood assessments were needed. However, our study, which to our knowledge is the first report describing the changes in the endocrine factors FGF19 and FGF21 in the human fetal-to-neonatal transition and in the first months of life, allowed us to obtain relevant conclusions.

FGF19 and FGF21 were strikingly low at birth independently of prenatal growth. FGF19 showed a delayed induction until the infants suckled high fat-containing mature milk; accordingly, it is tempting to speculate that, given the role of FGF19 in the control of bile acid homeostasis in response to intestinal lipid handling, it is only when fat is substantially present in milk that FGF19 is upregulated. Besides, the neonatal gut is quite immature at birth and requires postnatal development to achieve a mature function;34 this may also explain in part the delayed induction of FGF19, which is synthesized in the intestine. Delayed induction of the expression of the FGF15, the ortholog of the FGF19 gene in rodents, occurs also during the postnatal development of the mouse intestine (unpublished data). In contrast, breastfeeding induced an early surge of FGF21 in the first week of life, confirming the influence of nutrition on the induction of this factor. In fact, previous observations in mice indicate that the initiation of suckling not only modifies FGF21 gene expression in the liver, but also results in a massive increase in circulating FGF21.24

We also assessed longitudinally the circulating levels of FGF19 and FGF21 in AGA and SGA infants at birth and at the age of 4 months. The lower levels of FGF19 in SGA infants as compared with AGA infants at 4 months might be among the factors potentially influencing the subsequent SGA-associated risks to develop metabolic abnormalities. Indeed, FGF19 has been reported to activate an insulin-independent endocrine pathway that regulates hepatic protein and glycogen metabolism.6 Thus, the decreased levels of FGF19 may reflect the reduced metabolic capacity of SGA infants early in life.34 Along these lines, Boehm et al.34 reported higher serum levels of bile acids from postnatal day 8 to day 42 in SGA infants, presumably as a result of hepatocellular dysfunction. Increased levels of bile acids at 4 months are consistent with the decrease in FGF19 concentrations, in line with the repressor action of FGF19 on bile acid synthesis observed in adults.5 In contrast, FGF21 concentrations were comparable in both groups throughout follow-up.

FGF19 and HMW adiponectin correlated positively at the age of 4 months in AGA and SGA infants; these findings might in part relate to the more favorable outcome in insulin sensitivity in AGA vs SGA infants later in postnatal life. To our knowledge, no data on the association between FGF19 and adiponectin levels have been reported previously in humans.

At birth, FGF21 showed a positive correlation with HMW adiponectin in both subgroups of newborns. This finding is in agreement with recent studies in mice showing an enhancing effect of FGF21 in both the expression and secretion of adiponectin.35 At the age of 4 months, FGF21 correlated positively with ponderal index in AGA and SGA infants and inversely with fasting insulin and homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance only in SGA infants. FGF21 has been recognized to improve insulin sensitivity and to increase energy expenditure.1, 13, 14 However, in humans, a paradoxical scenario has been reported, with positive correlations between FGF21 and indicators of insulin resistance.16, 19, 20 Our results would indicate for the first time that FGF21 may be exerting its insulin-sensitizing properties early in life in individuals at higher risk for developing insulin resistance.

In summary, we report for the first time the longitudinal changes of FGF19 and FGF21 in human newborns over the first year of life, indicating a dramatic surge in early life. These factors, especially FGF19, may be involved in the altered regulation of the endocrine–metabolic status in SGA infants. These results may provide novel key insights on the metabolic adaptation of SGA infants and on the potential higher risk of these individuals to develop obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

References

Kharitonenkov A, Shiyanova TL, Koester A, Ford AM, Micanovic R, Galbreath EJ et al. FGF-21 as a novel metabolic regulator. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 1627–1635.

Badman MK, Pissios P, Kennedy AR, Koukos G, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E . Hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by PPAR alpha and is a key mediator of hepatic lipid metabolism in ketotic states. Cell Metab 2007; 5: 426–437.

Inagaki T, Dutchak P, Zhao G, Ding X, Gautron L, Parameswara V et al. Endocrine regulation of the fasting response by PPAR alpha-mediated induction of fibroblast growth factor 21. Cell Metab 2007; 5: 415–425.

Badman MK, Koester A, Flier JS, Kharitonenkov A, Maratos-Flier E . Fibroblast growth factor 21-deficient mice demonstrate impaired adaptation to ketosis. Endocrinology 2009; 150: 4931–4940.

Inagaki T, Choi M, Moschetta A, Peng L, Cummins CL, McDonald JG et al. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab 2005; 2: 217–225.

Kir S, Beddow SA, Samuel VT, Miller P, Previs SF, Suino-Powell K et al. FGF19 as a postprandial, insulin-independent activator of hepatic protein and glycogen synthesis. Science 2011; 331: 1621–1624.

Novotny D, Vaverkova H, Karasek D, Lukes J, Slavik L, Malina P et al. Evaluation of total adiponectin, adipocyte fatty acid binding protein and fibroblast growth factor 21 levels in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Physiol Res 2014; 63: 219–228.

Nishimura T, Nakatake Y, Konishi M, Itoh N . Identification of a novel FGF, FGF-21, preferentially expressed in the liver. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000; 1492: 203–206.

Mai K, Andres J, Biedasek K, Weicht J, Bobbert T, Sabath M et al. Free fatty acids link metabolism and regulation of the insulin-sensitizing fibroblast growth factor-21. Diabetes 2009; 58: 1532–1538.

Gaich G, Chien JY, Fu H, Glass LC, Deeg MA, Holland WL et al. The effects of LY2405319, an FGF21 analog, in obese human subjects with type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab 2013; 18: 333–340.

Adams AC, Coskun T, Rovira AR, Schneider MA, Raches DW, Micanovic R et al. Fundamentals of FGF19 & FGF21 action in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 2012; 7: e38438.

Fisher FM, Estall JL, Adams AC, Antonellis PJ, Bina HA, Flier JS et al. Integrated regulation of hepatic metabolism by fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) in vivo. Endocrinology 2011; 152: 2996–3004.

Coskun T, Bina HA, Schneider MA, Dunbar JD, Hu CC, Chen Y et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 corrects obesity in mice. Endocrinology 2008; 149: 6018–6027.

Micanovic R, Raches DW, Dunbar JD, Driver DA, Bina HA, Dickinson CD et al. Different roles of N- and C-termini in the functional activity of FGF21. J Cell Physiol 2009; 219: 227–234.

Mráz M, Lacinová Z, Kaválková P, Haluzíková D, Trachta P, Drápalová J et al. Serum concentrations of fibroblast growth factor 19 in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: the influence of acute hyperinsulinemia, very-low calorie diet and PPAR-α agonist treatment. Physiol Res 2011; 60: 627–636.

Gallego-Escuredo JM, Gómez-Ambrosi J, Catalan V, Domingo P, Giralt M, Frühbeck G et al. Opposite alterations in FGF21 and FGF19 levels and disturbed expression of the receptor machinery for endocrine FGFs in obese patients. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015; 39: 121–129.

Gerhard GS, Styer AM, Wood GC, Roesch SL, Petrick AT, Gabrielsen J et al. A role for fibroblast growth factor 19 and bile acids in diabetes remission after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 1859–1864.

Woo YC, Xu A, Wang Y, Lam KS . Fibroblast growth factor 21 as an emerging metabolic regulator: clinical perspectives. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013; 78: 489–496.

Chavez AO, Molina-Carrion M, Abdul-Ghani MA, Folli F, DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D . Circulating fibroblast growth factor-21 is elevated in impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes and correlates with muscle and hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 1542–1546.

Mashili FL, Austin RL, Deshmukh AS, Fritz T, Caidahl K, Bergdahl K et al. Direct effects of FGF21 on glucose uptake in human skeletal muscle: implications for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2011; 27: 286–297.

Hanks LJ, Casazza K, Ashraf AP, Wallace S, Gutiérrez OM . Fibroblast growth factor-21, body composition, and insulin resistance in pre-pubertal and early pubertal males and females. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014; e-pub ahead of print 10 July 2014; doi:10.1111/cen.12552.

Ko BJ, Kim SM, Park KH, Park HS, Mantzoros CS . Levels of circulating selenoprotein P, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 21 and FGF23 in relation to the metabolic syndrome in young children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014; 38: 1497–1502.

Bisgaard A, Sørensen K, Johannsen TH, Helge JW, Andersson AM, Juul A . Significant gender difference in serum levels of fibroblast growth factor 21 in Danish children and adolescents. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2014; 2014: 7.

Hondares E, Rosell M, Gonzalez FJ, Giralt M, Iglesias R, Villarroya F . Hepatic FGF21 expression is induced at birth via PPAR alpha in response to milk intake and contributes to thermogenic activation of neonatal brown fat. Cell Metab 2010; 11: 206–212.

Levin BE . Metabolic imprinting: critical impact of the perinatal environment on the regulation of energy homeostasis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2006; 361: 1107–1121.

Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR . Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics 2005; 115: e290–e296.

Harder T, Rodekamp E, Schellong K, Dudenhausen JW, Plagemann A . Birth weight and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 165: 849–857.

Kerkhof GF, Hokken-Koelega AC . Rate of neonatal weight gain and effects on adult metabolic health. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012; 8: 689–692.

Ibáñez L, Sebastiani G, Lopez-Bermejo A, Díaz M, Gómez-Roig MD, de Zegher F . Gender specificity of body adiposity and circulating adiponectin, visfatin, insulin, and insulin growth factor-I at term birth: relation to prenatal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 2774–2778.

Ibáñez L, Sebastiani G, Diaz M, Gómez-Roig MD, Lopez-Bermejo A, de Zegher F . Low body adiposity and high leptinemia in breast-fed infants born small-for-gestational-age. J Pediatr 2010; 156: 145–147.

Ferrández-Longás A, Mayayo E, Labarta JI, Bagué L, Puga B, Rueda C et al. Estudio longitudinal de crecimiento y desarrollo. Centro Andrea Prader. Zaragoza. García-Dihinx A, Romo A, Ferrández-Longás A (eds) Patrones de crecimiento y desarrollo en España. Atlas de gráficas y tablas. 1st edn. Madrid: ERGON, 1980–2002; pp 61–115.

de Zegher F, Sebastiani G, Diaz M, Sánchez-Infantes D, Lopez-Bermejo A, Ibáñez L . Body composition and circulating High-Molecular-Weight adiponectin and IGF-I in infants born small for gestational age: breast- versus formula-feeding. Diabetes 2012; 61: 1969–1973.

Domingo P, Gallego-Escuredo JM, Domingo JC, Gutierrez MM, Mateo MG, Fernandez I et al. Serum FGF21 levels are elevated in association with lipodystrophy, insulin resistance and biomarkers of liver injury in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 2010; 24: 2629–2637.

Boehm G, Senger H, Müller D, Beyreiss K, Räihä NC . Metabolic differences between AGA-and SGA-infants of very low birthweight. III. Influence of postnatal age. Acta Paediatr Scand 1989; 78: 677–681.

Lin Z, Tian H, Lam KS, Lin S, Hoo RC, Konishi M et al. Adiponectin mediates the metabolic effects of FGF21 on glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in mice. Cell Metab 2013; 17: 779–789.

Acknowledgements

DS-I is an Investigator of the Sara Borrell Fund from Carlos III National Institute of Health, Spain. MD and LI are Clinical Investigators of CIBERDEM (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas Asociadas, www.ciberdem.org). FdZ is a Clinical Investigator supported by the Clinical Research Council of the University Hospital Leuven. FV is an Investigator of CIBEROBN (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición). This study was supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF 2011-23636), Recercaixa, Instituto de Salud Carlos III and by the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), Madrid, Spain (PI11/0443).

Author Contributions

DS-I contributed to the design and acquisition of data and drafted the manuscript; JMG-E contributed to data acquisition and helped in writing the manuscript; MD, GA and GS contributed to data acquisition and reviewed the manuscript; AL-B contributed to data acquisition and to discussion of the paper; FdZ and FV contributed to interpretation of the data and reviewed the manuscript; PD contributed to data acquisition; LI contributed to conception and the interpretation of data and reviewed the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez-Infantes, D., Gallego-Escuredo, J., Díaz, M. et al. Circulating FGF19 and FGF21 surge in early infancy from infra- to supra-adult concentrations. Int J Obes 39, 742–746 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.2

This article is cited by

-

FGF21 via mitochondrial lipid oxidation promotes physiological vascularization in a mouse model of Phase I ROP

Angiogenesis (2023)

-

The endocrine role of brown adipose tissue: An update on actors and actions

Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (2022)

-

BMP8 and activated brown adipose tissue in human newborns

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Developmental Programming of Body Composition: Update on Evidence and Mechanisms

Current Diabetes Reports (2019)

-

Long-term metabolic risk among children born premature or small for gestational age

Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2017)