Abstract

Objective:

Early-life growth characteristics and in particular age at adiposity rebound (AR), have been shown to impact nutritional status later in life but studies investigating the association with long-term health remain scarce. Our aims were to identify determinants of age at AR and its relationship with nutritional status and cardiometabolic risk factors at adulthood.

Design:

A total of 1465 subjects aged 20–60 years participated in this retrospective cohort study. Height, weight, waist circumference, blood glucose, lipids and blood pressure were measured at adulthood. Childhood weight, height, gestational age, birth weight and early nutrition were collected retrospectively from health booklets and age at AR was assessed. Participants self-reported parental silhouettes. Associations were assessed using multiple linear and logistic regression.

Results:

An earlier AR was associated with higher body mass index and waist circumference at adulthood in both men and women (P<0.0001). In addition, women with an earlier occurrence of AR had higher triglyceride (P=0.001), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (P=0.001), systolic (P=0.02) and diastolic blood pressure (P=0.04) at adulthood. Both men (odds ratio (OR) (95% confidence interval (CI)): 0.82 (0.70–0.95)) and women (OR (95% CI): 0.84 (0.73–0.96) with an AR occurring earlier were more likely to develop a metabolic syndrome. Larger parental silhouette was associated with an earlier AR.

Conclusions:

This long-term study showed that age at AR was associated with nutritional status and metabolic syndrome at adulthood. These results highlight the importance of monitoring childhood growth so as to help identify children at risk of developing an adverse cardiometabolic profile in adulthood. AR determinants for use in overweight surveillance were identified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity and the metabolic syndrome are major causes of chronic diseases and death worldwide.1, 2 The potential impact of early-life growth factors on later health outcome has generated substantial interest in the literature. In particular, several critical periods in early life have been pointed out, including that of adiposity rebound (AR).3 In general, a rapid increase in body mass index (BMI) occurs during the first year of life. BMI subsequently declines and reaches a minimum at around the age of 6 years, prior to the occurrence of a sustained increase until the end of growth. The point of the minimal BMI value (the nadir of the BMI curve) corresponds to AR.3 Definition of an early adiposity rebound varies in the literature; some studies define it as occurring before 4 years,4 whereas some others used 5(ref. 5) or 5.5 years3 as cutoff points. Some authors also considered a different threshold in boys (5.5 years) and girls (5 years)6 Numerous epidemiological studies have clearly shown that AR occurring at a younger age is associated with increased risk of overweight or obesity in adolescence or adulthood.7, 8, 9 The few studies focusing on waist circumference have shown an association between an earlier AR and higher waist circumference in childhood10 or adulthood.11 In addition, a number of studies have also demonstrated that individuals with an AR occurring earlier were more likely to have impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes.12, 13, 14, 15 However, studies focusing on metabolic syndrome are rare. Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of risk factors (blood pressure, dyslipidemia (raised triglycerides and lowered high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol), raised fasting glucose, and central obesity) for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD), where three abnormal findings out of five qualify a person for this condition. An early AR was found to be associated with metabolic status at ages 7 years16 and 12 years,4 whereas only one study provided evidence that an AR occurring earlier is associated with metabolic risk factors in adulthood including triglycerides, insulin, blood glucose and metabolic syndrome.11 In addition, although mean age at AR,6 and prevalence of cardiometabolic abnormalities17 have been shown to differ between men and women, no study has investigated potential sex differences in the association between these two parameters. Further work is therefore needed to confirm previous results, taking into account potential differences between men and women.

Although the importance of AR has been clearly demonstrated, its determinants have not been thoroughly elucidated.8 Several studies in the literature suggest that children with early rebound often have obese parents; however, it is unclear as to whether associations are similar in the two genders.18, 19 Early nutrition may also have an impact, but data are scarce and thus far inconclusive.8, 20, 21, 22

The aim of this study was to determine, in a sample of 1465 individuals, whether age at AR is associated with BMI, waist circumference, cardiometabolic risk factors individually (that is, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)- and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, fasting glycemia, systolic and diastolic blood pressure), and the metabolic syndrome defined according to the sets of criteria proposed by the Joint Interim Statement (JIS) in adulthood. In addition, we sought to investigate early as well as parental determinants of age at AR.

Patients and methods

Population

The sample was selected from a pool of 24 574 adults attending one of the health examination centers in the central/western part of France (parts of 3 regions: Centre, Pays de la Loire and Normandie) from September 2008 to July 2009. All individuals affiliated with the General French national health insurance system (corresponding to about 85% of the French population) are able to benefit from a free medical and laboratory check-up every 5 years. The population is generally aware of this possibility and practical information is publicly available. All adults attending health centers traditionally complete a set of questionnaires that focus on diet, physical activity, lifestyle, socioeconomic conditions and health status. In addition, a clinical examination and blood sampling are performed.

Subjects participating in the CECA (child growth and metabolic outcome at adulthood) study were asked to fill in an additional growth questionnaire that included information on parental characteristics, nutrition in early life and anthropometric data during childhood, and to bring along to the medical check-up their health booklets containing these data. In order to be included in the study, subjects had to have brought the health booklet to the examination and completed the growth questionnaire. Data collection by the examination centers was approved by the Comité National Informatique et Liberté (CNIL number26674) and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Data collection

Socioeconomic and lifestyle characteristics

Self-administred questionnaires were completed by all participants and verified by the physician performing the health examination interview. Sex, age, physical activity (⩽30 min per day, 30–60 min per day, >60 min per day) and occupational category (managerial staff, intermediate profession, employee or manual worker, unemployed, never-employed and retired) were provided. The deprivation level of each participant was assessed using the ‘Evaluation of Deprivation and Inequalities of Health in Healthcare Centers’ score (EPICES).23 The EPICES score is calculated based on answers to 11 questions (for example, are there periods in the month when you have real financial difficulties to face your needs (food, rent and electricity)?) and varies from 0 to 100, from the least deprived to the most deprived situation. Gestational age (weeks), birth weight (g) and nutrition when leaving the maternity ward (exclusive or partial breastfeeding and formula feeding) were collected using the data from the health booklets. Breastfeeding was defined as any kind of breastfeeding, including partial breastfeeding, whatever the duration. Parental silhouette was estimated using nine figural stimuli.24 Subjects were asked to choose the silhouettes that most closely resembled those of their parents at the maximal BMI attained during their lifetime.

Growth measurements during infancy

Data were obtained from health booklets. Health booklets have been distributed by the Ministry of Health to parents of all newborns in France since 1945. They are intended to record anthropometry, measured by health practitioners, and health events during childhood, from birth on. Subjects were asked to report the weight and height data that had been recorded by health practitioners at birth and at specific periods during childhood: one measurement of weight and length/height at around 1 month, 3 months, 6 months and 9 months of age; two measurements between 1 and 2 years, between 2 and 3 years, and between 3 and 4 years; and finally, one measurement at around 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 years of age. Subjects were also asked to report the exact date and/or age a each reported measurement. These data were reported on a questionnaire that was subsequently checked by medical staff at the Health center. We calculated BMI (weight in kg divided by squared height in m) for each data point and drew individual growth curves. Prevalence of overweight (including obesity) was assessed at age 6 years using extended international (IOTF) definition.25 Age at AR corresponding to the nadir in the BMI growth curves3 was estimated visually as advised.26 The following criteria were applied: (1) age at lowest BMI value between ages 2 and 10 years; (2) subsequent BMI values at least 0.1 kg m−2 higher; and (3) in case of a plateau (two consecutive equal values), use of the last value. In addition, when no decrease in the curve followed the BMI peak at 1 year, age at AR was set at 1 year. This was arbitrarily decided because an increase of BMI at a time when BMI should decrease (after 1 year) demonstrates that the rebound had occurred. When no increase in the curve could be observed after the age of 7 years, the least available value was selected (never exceeding 10 years). Two independent raters trained in assessment of age at AR determined this value for all individual growth curves comprising at least 5 weight/height values. Interrater reliability was very good with an ICC of 0.92. When the data from the raters did not match, curves were reviewed by two additional experts. Finally, early AR was defined as an AR occurring before the age of 5 years in women and 5.5 years in men as proposed.6

Biological and biometric data and anthropometry at adulthood

Weight, height and waist circumference were measured in the health examination centers by trained nurses, with participants wearing only underwear, according to standardized procedures.27 Waist circumference was measured by the physician as the smallest horizontal circumference between the costal margin (lower edge of the chest formed by the bottom edge of the rib cage) and the iliac crests (superior border of the ilium). Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with a Seca stadiometer (Seca GmbH & Co. KG, Hamburg, Germany). Sitting diastolic and systolic blood pressures were measured by an OMRON automatic tensiometer (Omron HEM-705CP; Omron Healthcare/DuPont Medical, Frouard, France) in subjects who had been lying down for at least 5 min. Blood samples were collected in the morning after at least 8 h of fasting. All samples were assayed using a C8000 Architect Abbott analyzer (Rungis, France). Plasma glucose was assayed by the hexokinase procedure. HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides were assayed by an enzymatic method. Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the sets of criteria proposed by the Joint Interim Statement (JIS).28 Individuals had to present at least three of the following criteria: (1) waist circumference⩾94 cm (men), ⩾80 cm (women); (2) fasting plasma glucose⩾5.6 mmol l−1 or antidiabetic medication; (3) triglycerides⩾1.7 mmol l−1 or medication for elevated triglycerides; (4) HDL-cholesterol<1.03 mmol l−1 (men) or <1.29 mmol l−1 (women) or medication for reduced HDL-cholesterol; (5) blood pressure ⩾130/85 mm Hg or blood-pressure-lowering medication. Information on medication use was collected by physicians.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of subjects at childhood and adulthood are presented as frequencies for categorical variables and means plus s.d. for continuous variables. All analyses were stratified on sex. Comparisons between groups were performed using χ2-tests for categorical variables and the Student's t-test for continuous variables. The association between age at AR and characteristics during childhood as well as parental characteristics was estimated with multiple linear regression analysis. The association between age at AR and adult cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome was estimated using multiple linear and logistic regression analysis, respectively. The association between age at AR and adulthood characteristics were computed using two models. Model 1 was adjusted for age at adulthood; model 2 was additionally adjusted for physical activity, EPICES score, mother’s and father’s silhouettes and birth weight. P-values were two-sided and significance was set at 5%. All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the sample

Among the consultants at the health centers, 2549 (10.4%) completed the growth questionnaire and brought their health booklets to the medical check-up. We excluded 14 subjects who had missing weight/height data at adulthood and 28 women who were pregnant at the time of examination. In addition, we excluded 595 subjects who had fewer than 5 weight/height data between birth and 10 years because it is not sufficient for an accurate assessment of the age at AR, and a further 447 subjects for whom AR could not be assessed. Thus, our final study population consisted of 1465 participants. Compared with excluded subjects, included subjects were younger (29.4±7.3 years in included subjects vs 36.7±9.1 in excluded subjects, P<0.0001), more often belonged to the category ‘unemployed, never-employed, retired’ (32.2% vs 22.1%, P<0.0001) and had higher EPICES score (21.3±17.8 vs 19.3±18.9, P<0.0001) and lower BMI at adulthood (23.4±4.0 vs 24.0±4.1, P=0.0005). In addition, excluded and included subjects showed no statistically significant differences in sex ratio and physical activity (all P>0.05), and no difference in age at AR or BMI at AR (among subjects who had an AR which could be assessed; all P>0.05).

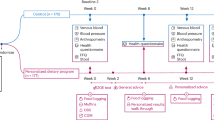

Table 1 shows characteristics of men (41.3%) and women (58.7%) included in the study. Compared with women, men had fathers with larger silhouettes, more missing data on early nutrition and less-frequent low birth weight. AR occurred later and they were less frequently overweight at 6 years of age. In addition, they were older, less often in the category ‘unemployed, never-employed, retired’ and more often in the category ‘managerial staff’; they had lower EPICES score, higher physical activity levels, higher BMI and larger waist circumference at adulthood. Finally, they had lower HDL-cholesterol and higher LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glycemia, systolic and diastolic blood pressure and a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Figure 1 shows BMI curves of participants with early AR and with average or late AR.

BMI growth curves of participants with early adiposity rebound (⩽5 years in girls and 5.5 years in boys) and average or late adiposity rebound (>5 years in girls and 5.5 years in boys), plotted together with the French reference charts (3rd, 50th, 97th percentiles)56 between 0 and 10 years (N=1465, CECA growth study, 2008–2009).

Association between timing of adiposity rebound and childhood and parental characteristics

Table 2 shows the association between age at AR and childhood and parental characteristics using linear regression analysis. Earlier age at AR was associated with a larger maternal silhouette for both men and women. In women, earlier age at AR was, in addition, associated with the paternal silhouette.

Association between timing of adiposity rebound and cardiometabolic risk factors at adulthood

Table 3 shows the association between age at AR and cardiometabolic risk factors at adulthood using linear regression analysis. In men and women, earlier age at AR was associated with higher BMI and waist circumference at adulthood. In addition, in women, earlier AR was associated with higher triglyceride levels, LDL-cholesterol and diastolic and systolic blood pressure. Sensitivity analyses performed in a subsample of children weighing⩾2500 g at birth showed similar results. In addition, using logistic regression analysis we assessed the association between age at AR and cardiometabolic risk factors using thresholds of the metabolic syndrome definition. These analyses showed similar results compared with linear regression analysis.

Association between timing of adiposity rebound and the metabolic syndrome during adulthood

Table 4 shows the association between age at AR and the metabolic syndrome risk using multiple logistic regression analysis. Results were similar for men and women. Results showed that AR occurring at an earlier age was associated with higher ORs of the metabolic syndrome in both models. Sensitivity analyses performed in a subsample of children weighing⩾2500 grams at birth showed similar results.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study that included 1465 participants, we showed that earlier AR was strongly associated with increased BMI, waist circumference and the metabolic syndrome at adult age in both men and women. In addition, in women, earlier AR was associated with higher triglyceride and LDL-cholesterol levels and systolic and diastolic pressure. The parental silhouette was found to be an important determinant of age at AR.

Determinants of adiposity rebound

Age at AR is in line with the data from other cohorts born during the same periods.3, 7 A number of studies have shown that children born more recently had an AR generally occurring at an earlier age.7, 8 Our results indicated that a larger maternal silhouette was associated with AR occurring earlier in both men and women. The father’s silhouette was also of importance, but only in women. These associations remained after adjustment for the other variables. Similar results were observed in the literature with AR occurring earlier in children whose parents had high BMI.18, 19 Sex specificities were observed in one of these studies, with the mother’s BMI impacting AR in men only, whereas the father’s BMI impacted AR in women only.19 These results suggest that parental weight is important in determining the timing of AR and point to the fact that children of overweight parents may be valid targets for obesity prevention programs. Studies have shown that growth trajectories of children with obese parents differ from those of children having normal-weight parents29, 30 and that the former children have higher risk of becoming overweight or obese,31 probably due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors.32 Reasons behind these sex differences may be explained by different patterns of growth in boys and girls.33, 34 In addition, previous studies provided evidence that the environment may more strongly affect growth in boys than in girls, as the latter are better protected against environmental stress.35

Our data showed no association between birth weight and age at AR, as previously found7, 18, 36 and BMI trajectories in subjects with early or average and late rebounds were similar during the first years of life prior to AR as reported earlier.3, 18, 37 Finally, our data showed no influence of breastfeeding on age at AR. In contrast, in the literature breastfeeding was reported to have an important role in the timing of AR.21 Potential reasons included human milk composition, which contains low amounts of proteins and high amounts of fat. Indeed, the previous data showed that excessive amount of protein in the young child’s diet is associated with early AR, leading to increased body fatness at the trunk (subscapular skinfold), but not at the extremity (triceps skinfold) site.20 Besides, low-fat intake was also found to be associated with increased body fatness at the trunk site,38 however, it was not associated with the age at AR.20 Data on this topic remain scarce and the role of early nutrition in the timing at AR warrants further investigation.7, 8 Early feeding practices39 and, in particular, breastfeeding have been previously shown to influence the infant growth pattern.40 However, the effect of breastfeeding on risk of overweight and obesity during childhood remains unclear.41, 42 Studies indicating protective effects against obesity may reflect uncontrolled bias caused by confounding and selection.43 The absence of a relationship observed in the present study could also be partly owing to the extended definition of breastfeeding chosen in this study (partial and exclusive breastfeeding, any duration of breastfeeding) and to the fact that, in France, breastfeeding duration is generally short.44 Regional data indicate a median duration of breastfeeding of 10 weeks,45 while WHO recommend 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding.46

Timing of adiposity rebound, BMI and waist circumference

In our sample, we showed that younger age at AR was strongly associated with higher BMI at adulthood in both men and women. This is in line with the data from the literature indicating that earlier timing of AR was associated with higher BMI3, 47 and higher overweight/obesity risk6, 48, 49 at adulthood. Only one study in the literature suggested sex differences observing no association in men, but an association in women.50 Our results also support previous evidence of a relationship between timing of AR and waist circumference in both men and women.6, 11 The literature has shown that differences in BMI during AR are mainly due to alterations in body fat, rather than lean mass or height, and that children with early AR gain fat more rapidly than those who rebound at a later age.37, 51

Adiposity rebound, cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome

Our data suggest a sex-specific association between an AR occurring earlier and subsequent risks. In men, timing of AR was not associated with any of the cardiometabolic risk factors assessed (that is, triglycerides, HDL- and LDL-cholesterol, fasting glycemia, systolic and diastolic pressure), whereas in women, AR occurring later was protective in terms of triglycerides and LDL-cholesterol levels, and systolic and diastolic pressure. Although there is strong evidence of a relationship between age at AR and later overweight, studies on an association with long-term cardiometabolic risk factors are rare, especially in adulthood. One study that did not carry out sex-specific analyses showed that AR occurring at an earlier age was associated with higher triglycerides and blood glucose level at adulthood.11 A negative association was also found with glucose and triglyceride levels in 7-year-old children,16 with triglycerides and blood pressure (in boys) in 12-year-old children4 and with systolic blood pressure in 14-year-old children.10 However, those studies were performed in children and confounders were not always taken into account.

Our data show that early AR was associated with increased risk of the metabolic syndrome in adulthood in both men and women. In the literature, an AR occurring later had a protective effect on adult metabolic syndrome risk when considering adult and early-life cofactors.11 Another study indicated a significant association between an early AR and an adverse metabolic score risk at 7 years of age.16 Interestingly, the data showed that AR had no influence on individual cardiometabolic risk factors in men, whereas such an influence was found when considering a cluster of risk represented by the metabolic syndrome. A potential explanation could involve a threshold effect and the fact that subjects taking medication are not excluded from analysis of cardiometabolic risk factors. Medication is likely to have normalized cardiometabolic risk factor levels and to have reduced the magnitude of the association between age at AR and later outcome. However, it must be noted that sensitivity analysis using logistic regression showed similar results.

Strengths and limitations of the study

One strength of our study lies in the data collection over a long time period in a large sample of individuals and the large number of nutritional status and cardiometabolic indicators available at adult age. The mean of around 10 weight/length measurements per individual between the ages of 0 and 10 years and the use of several assessors to visually estimate AR as advised26 enables accurate AR assessment. However, it cannot be excluded that the timing of AR was inaccurate in individuals with a more limited number of growth data available. A limitation of our study was the fact that anthropometric data in infancy were recorded retrospectively in health booklets. However, those measurements were performed and recorded by physicians, limiting potential bias in measurements. Study participation rate was relatively low due to some individuals forgetting their growth questionnaire or health booklet at home, others who had never received a health booklet or lost it, and still others who had no data in the health booklet. Thus, these results cannot be generalized to all populations and need to be replicated in different contexts. However, our sample showed an obesity prevalence (IMC⩾30; 7.2% in included subjects and 7.9% in excluded subjects) similar to that of the whole sample of subjects who went to the examination center after standardization with the French age distribution (8.9% in men vs 8.6% in women) in 2005.52 Another limit pertains to the use of silhouette to recall maximal parental BMI attained during life since this type of measure can be biased by retrospective recall. In addition, maximal weight attained during life might be due to specific life event and not be characteristic of an individual’s weight throughout life. A secular trend of earlier AR has been reported in various countries including France.7, 53, 54 Our data also suggest such trend. Subjects with an early AR were younger (mean age: 28.7±6.6 years in men and 26.5±5.9 years in women) compared with those demonstrating an average or late AR (mean age: 30.7±7.4 years in men and 29.8±7.6 years in women; both P<0.001) possibly impacting the observed associations. However, this potential impact was limited by including age at adulthood as a confounder in the analyses. Finally, although a wide range of co-variates were taken into account, other potential confounders such as early dietary intake43 or smoking55 may have also had a role in the associations.

Conclusions

This study shows that AR predicts long-term risk of overweight and metabolic syndrome and that it is associated with parental silhouette. These observations confirm previous shorter follow-up and point out that early life is a critical period for the onset of overweight and associated risks in adulthood. AR is then an important marker to be considered in studies investigating health risks during childhood. These findings support the notion that regular monitoring of weight and height during childhood may help to identify children at risk of developing adverse cardiometabolic profile in adulthood.

References

Sundstrom J, Riserus U, Byberg L, Zethelius B, Lithell H, Lind L . Clinical value of the metabolic syndrome for long term prediction of total and cardiovascular mortality: prospective, population based cohort study. BMJ 2006; 332: 878–882.

WHO Global Atlas On Cardiovascular Disease Prevention And Control. In: Mendis S Puska P, Norrving B (eds). World Health Organization: Geneva, 2011.

Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Bellisle F, Sempe M, Guilloud-Bataille M, Patois E . Adiposity rebound in children: a simple indicator for predicting obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 1984; 39: 129–135.

Koyama S, Ichikawa G, Kojima M, Shimura N, Sairenchi T, Arisaka O . Adiposity rebound and the development of metabolic syndrome. Pediatrics 2014; 133: e114–e119.

Freedman DS, Kettel KL, Serdula MK, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS . BMI rebound, childhood height and obesity among adults: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 543–549.

Williams SM, Goulding A . Patterns of growth associated with the timing of adiposity rebound. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009; 17: 335–341.

Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Maillot M, Bellisle F . Early adiposity rebound: causes and consequences for obesity in children and adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006; 30 (Suppl 4): S11–S17.

Taylor RW, Grant AM, Goulding A, Williams SM . Early adiposity rebound: review of papers linking this to subsequent obesity in children and adults. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2005; 8: 607–612.

Dulloo AG, Jacquet J, Seydoux J, Montani JP . The thrifty 'catch-up fat' phenotype: its impact on insulin sensitivity during growth trajectories to obesity and metabolic syndrome. Int J Obes(Lond) 2006; 30 (Suppl 4): S23–S35.

Giussani M, Antolini L, Brambilla P, Pagani M, Zuccotti G, Valsecchi MG et al. Cardiovascular risk assessment in children: role of physical activity, family history and parental smoking on BMI and blood pressure. J Hypertens 2013; 31: 983–992.

Sovio U, Kaakinen M, Tzoulaki I, Das S, Ruokonen A, Pouta A et al. How do changes in body mass index in infancy and childhood associate with cardiometabolic profile in adulthood? Findings from the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 Study. Int J Obes(Lond) 2014; 38: 53–59.

Wadsworth M, Butterworth S, Marmot M, Ecob R, Hardy R . Early growth and type 2 diabetes: evidence from the 1946 British birth cohort. Diabetologia 2005; 48: 2505–2510.

Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Tuomilehto J, Osmond C, Barker DJ . Early adiposity rebound in childhood and risk of Type 2 diabetes in adult life. Diabetologia 2003; 46: 190–194.

Bhargava SK, Sachdev HS, Fall CH, Osmond C, Lakshmy R, Barker DJ et al. Relation of serial changes in childhood body-2mass index to impaired glucose tolerance in young adulthood. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 865–875.

Eriksson JG . Early growth and coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes: findings from the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study (HBCS). Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 94: 1799S–1802S.

Gonzalez L, Corvalan C, Pereira A, Kain J, Garmendia ML, Uauy R . Early adiposity rebound is associated with metabolic risk in 7-year-old children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014; 38: 1299–1304.

Vernay M, Salanave B, de PC, Druet C, Malon A, Deschamps V et al. Metabolic syndrome and socioeconomic status in France: The French Nutrition and Health Survey (ENNS, 2006-2007). Int J Public Health 2013; 58: 855–864.

Williams S, Dickson N . Early growth, menarche, and adiposity rebound. Lancet 2002; 359: 580–581.

Dorosty AR, Emmett PM, Cowin S, Reilly JJ . Factors associated with early adiposity rebound. ALSPAC Study Team. Pediatrics 2000; 105: 1115–1118.

Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Akrout M, Bellisle F . Influence of macronutrients on adiposity development: a follow up study of nutrition and growth from 10 months to 8 years of age. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1995; 19: 573–578.

Chivers P, Hands B, Parker H, Bulsara M, Beilin LJ, Kendall GE et al. Body mass index, adiposity rebound and early feeding in a longitudinal cohort (Raine Study). Int J Obes(Lond) 2010; 34: 1169–1176.

Gunther AL, Buyken AE, Kroke A . The influence of habitual protein intake in early childhood on BMI and age at adiposity rebound: results from the DONALD Study. Int J Obes(Lond) 2006; 30: 1072–1079.

Bihan H, Laurent S, Sass C, Nguyen G, Huot C, Moulin JJ et al. Association among individual deprivation, glycemic control, and diabetes complications: the EPICES score. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 2680–2685.

Bulik CM, Wade TD, Heath AC, Martin NG, Stunkard AJ, Eaves LJ . Relating body mass index to figural stimuli: population-based normative data for Caucasians. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 1517–1524.

Cole TJ, Lobstein T . Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes 2012; 7: 284–294.

Kroke A, Hahn S, Buyken AE, Liese AD . A comparative evaluation of two different approaches to estimating age at adiposity rebound. Int J Obes(Lond) 2006; 30: 261–266.

Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R . Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1988.

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA et alHarmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity Circulation 2009; 120: 1640–1645.

Magee CA, Caputi P, Iverson DC . Identification of distinct body mass index trajectories in Australian children. Pediatr Obes 2013; 8: 189–198.

Ventura AK, Loken E, Birch LL . Developmental trajectories of girls' BMI across childhood and adolescence. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009; 17: 2067–2074.

Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH . Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 869–873.

Demerath EW, Choh AC, Czerwinski SA, Lee M, Sun SS, Chumlea WC et al. Genetic and environmental influences on infant weight and weight change: the Fels Longitudinal Study. Am J Hum Biol 2007; 19: 692–702.

Ong KK . Size at birth, postnatal growth and risk of obesity. Horm Res 2006; 65: 65–69.

Pryor LE, Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Touchette E, Dubois L, Genolini C et al. Developmental trajectories of body mass index in early childhood and their risk factors: an 8-year longitudinal study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011; 165: 906–912.

Silventoinen K, Kaprio J, Lahelma E, Viken RJ, Rose RJ . Sex differences in genetic and environmental factors contributing to body-height. Twin Res 2001; 4: 25–29.

Hughes AR, Sherriff A, Ness AR, Reilly JJ . Timing of adiposity rebound and adiposity in adolescence. Pediatrics 2014; 134: e1354–e1361.

Rolland-Cachera MF, Akrout M, Péneau S . History and meaning of BMI. Interest of other anthropometric measurements Frelut ML The ECOG eBook on Child and Adolescent Obesity Available at http://ebook.ecog-obesity.eu/chapter-growth-charts-body-composition/history-meaning-body-mass-index-interest-anthropometric-measurements/ (accessed on 13 November 2015).

Rolland-Cachera MF, Maillot M, Deheeger M, Souberbielle JC, Peneau S, Hercberg S . Association of nutrition in early life with body fat and serum leptin at adult age. IntJObes(Lond) 2013; 37: 1116–1122.

Rolland-Cachera MF, Scaglioni S . Role of nutrients in promoting adiposity development Frelut ML The ECOG eBook on Child and Adolescent Obesity Available at http://ebook.ecog-obesity.eu/chapter-nutrition-food-choices-eating-behavior/role-nutrients-promoting-adiposity-development/ (accessed on 13 November 2015)..

Dewey KG . Growth characteristics of breast-fed compared to formula-fed infants. Biol Neonate 1998; 74: 94–105.

Cope MB, Allison DB . Critical review of the World Health Organization's (WHO) 2007 report on 'evidence of the long-term effects of breastfeeding: systematic reviews and meta-analysis' with respect to obesity. Obes Rev 2008; 9: 594–605.

Horta B L, Bahl R, Martines J C, Victora CG Evidence on the long-term effects of breastfeeding: systematic reviews and meta-analysis. World Health Organization. 2007.

Péneau S, Hercberg S, Rolland-Cachera MF . Breastfeeding, early nutrition, and adult body fat. J Pediatr 2014; 164: 1363–1368.

Castetbon K, Duport N, Hercberg S . Bases épidémiologiques pour la surveillance de l'allaitement maternel en France. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2004; 52: 475–482.

Lerebours B, Czernichow P, Pellerin AM, Froment L, Laroche T . [Infant feeding until the age of 4 months old in Seine-Maritime]. Arch Fr Pediatr 1991; 48: 391–395.

WHO. Exclusive breastfeeding. Available at http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/en/ (accessed on 13 November 2015).

Williams S, Davie G, Lam F . Predicting BMI in young adults from childhood data using two approaches to modelling adiposity rebound. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1999; 23: 348–354.

Whitaker RC, Pepe MS, Wright JA, Seidel KD, Dietz WH . Early adiposity rebound and the risk of adult obesity. Pediatrics 1998; 101: E5.

He Q, Karlberg J . Probability of adult overweight and risk change during the BMI rebound period. Obes Res 2002; 10: 135–140.

Guo SS, Huang C, Maynard LM, Demerath E, Towne B, Chumlea WC et al. Body mass index during childhood, adolescence and young adulthood in relation to adult overweight and adiposity: the Fels Longitudinal Study. IntJ Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000; 24: 1628–1635.

Taylor RW, Williams SM, Carter PJ, Goulding A, Gerrard DF, Taylor BJ . Changes in fat mass and fat-free mass during the adiposity rebound: FLAME study. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011; 6: e243–e251.

Czernichow S, Vergnaud AC, Maillard-Teyssier L, Peneau S, Bertrais S, Mejean C et al. Trends in the prevalence of obesity in employed adults in central-western France: a population-based study, 1995-2005. Prev Med 2009; 48: 262–266.

Vignerova J, Humenikova L, Brabec M, Riedlova J, Blaha P . Long-term changes in body weight, BMI, and adiposity rebound among children and adolescents in the Czech Republic. Econ Hum Biol 2007; 5: 409–425.

Johnson W, Soloway LE, Erickson D, Choh AC, Lee M, Chumlea WC et al. A changing pattern of childhood BMI growth during the 20th century: 70 y of data from the Fels Longitudinal Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2012; 95: 1136–1143.

Cena H, Fonte ML, Turconi G . Relationship between smoking and metabolic syndrome. Nutr Rev 2011; 69: 745–753.

Rolland-Cachera MF, Cole TJ, Sempe M, Tichet J, Rossignol C, Charraud A . Body Mass Index variations: centiles from birth to 87 years. Eur J Clin Nutr 1991; 45: 13–21.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the participants for their involvement in the study. We thank Véronique Gourlet for statistical analyses, Stefen Besseau for data management and Michèle Deheeger for assessment of adiposity rebound.

Author contributions

SP designed the protocol, supervised statistical analyses, interpreted data and drafted the manuscript. RG-C assessed adiposity rebound and critically revised the manuscript. GG, DG and OL collected the data and critically revised the manuscript. LF supervised statistical analyses and critically revised the manuscript. SH designed the protocol and critically revised the manuscript. M-FR-C designed the protocol, interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Péneau, S., González-Carrascosa, R., Gusto, G. et al. Age at adiposity rebound: determinants and association with nutritional status and the metabolic syndrome at adulthood. Int J Obes 40, 1150–1156 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.39

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.39

This article is cited by

-

Longitudinal association between the timing of adiposity peak and rebound and overweight at seven years of age

BMC Pediatrics (2022)

-

Sexual dimorphism of leptin and adiposity in children between 0 and 10 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Biology of Sex Differences (2022)

-

Age at adiposity rebound and the relevance for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis

International Journal of Obesity (2022)

-

Changing genetic architecture of body mass index from infancy to early adulthood: an individual based pooled analysis of 25 twin cohorts

International Journal of Obesity (2022)

-

Resolving early obesity leads to a cardiometabolic profile within normal ranges at 23 years old in a two-decade prospective follow-up study

Scientific Reports (2021)