Abstract

Upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) mucosal premalignant lesions include non-keratinizing and keratinizing intraepithelial dysplasia. The keratinizing type of intraepithelial dysplasia represents the majority of UADT dysplasias. Historically, grading of UADT dysplasias has followed a three tier system to include mild, moderate and severe dysplasia. Recent recommendations have introduced a two tier grading scheme to including low-grade (ie, mild dysplasia) and high-grade (moderate and severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ) providing for better consensus among pathologists in the interpretation of such dysplastic lesions. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignant neoplasm of the UADT. Several variants of squamous cell carcinoma are recognized among which the more common types include papillary squamous cell carcinoma, verrucous carcinoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma (sarcomatoid carcinoma) and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Each of these variants of squamous cell carcinoma poses diagnostic challenges and each correlates to specific therapy and prognosis. This review details the proposed update in the grading of UADT dysplasia to a two-tiered system as well as providing the key diagnostic features for select variants of squamous cell carcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Among the more common lesion types encountered in the daily practice of head and neck pathology are surface squamous epithelial alterations, including reactive hyperplasia and (intraepithelial) dysplasia. The majority of dysplastic lesions of the UADT are the keratinizing dysplasias.1 Owing to the potential development of invasive carcinoma from dysplasia wholly limited to the basal (lower third) epithelial layer in the setting of keratinizing dysplasia rather than full thickness intraepithelial dysplasia (ie, carcinoma in situ) as is often seen in non-keratinizing dysplasias, there often is a lack of consensus among pathologists in the histologic grading of these lesions potentially resulting in inappropriate therapy for the patient.2 In an attempt to enhance consensus and reproducibility, a two-tiered grading scheme has been suggested to include low-grade dysplasia and high-grade dysplasia.3

Invasive conventional type squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common malignancy of the head and neck. However, there are a number of histologic variants of SCC that are characterized by specific histomorphologic features and/or unique biologic behavior. The more common of these variants of SCC include papillary SCC, verrucous carcinoma, spindle cell squamous carcinoma (SCSC) and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (BSCC). This manuscript will detail the diagnostic criteria for each of these variants. Viral-associated head and neck cancers including oropharyngeal HPV-associated carcinoma and nasopharyngeal EBV-associated carcinoma are covered elsewhere in this monograph.

Dysplasia of the upper aerodigestive tract

Histologic criteria for the diagnosis of intraepithelial neoplasia of the UADT include both cytomorphologic and maturation abnormalities.3 These alterations include the proliferation of immature or ‘uncommitted’ cells characterized by a loss of cellular organization or polarity, nuclear pleomorphism (variations in the size and shape of the nuclei), increase in nuclear size relative to the cytoplasm, increase in the nuclear chromatin (hyperchromasia) with irregularity of distribution, and increased mitoses, including atypical forms in all epithelial layers. The dysplastic changes may or may not be associated with keratosis and/or dyskeratosis.

The paradigm for grading epithelial dysplasia is the one used for the uterine cervix. In the uterine cervix the ‘classic’ or non-keratinizing form of dysplasia commonly occurs. The increasing gradations of cervical dysplasia include mild (CIN I), moderate (CIN II), and severe (CIN III) with the latter representing full thickness replacement of the squamous epithelium by atypical, small, immature basaloid cells and is referred to as carcinoma in situ (CIS). A two-tiered grading scheme (Bethesda classification) is utilized to include low-grade squamous intraepithelial dysplasia encompassing CIN I or mild dysplasia and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion encompassing CIN II and III or moderate and severe dysplasia into a single category.4 This grading scheme is reproducible and is clinically useful.4 In the UADT, the ‘classic’ or non-keratinizing dysplasia that typifies the uterine cervical dysplasia is uncommon. Rather, most dysplastic lesions of the UADT are the keratinizing type. The criteria for evaluating keratinizing dysplasias are less defined and the diagnosis of keratinizing moderate and severe dysplasia has been imprecise and often subjective. The definition of severe dysplasia in the UADT, especially in the laryngeal glottis is broader than the highly reproducible pattern seen in the uterine cervix and includes a microscopically heterogeneous group of lesions.2 In the setting of keratinizing dysplasia where surface maturation is retained with only partial replacement of the epithelium by atypical cells, severe dysplasia includes those lesions in which the epithelial alterations are so severe that there would be a high probability for the progression to an invasive carcinoma if left untreated.

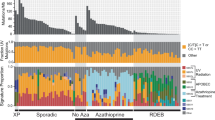

Given the complexities in the issues relative to UADT dysplastic lesions, confusion, and misunderstandings may occur between the clinician and the pathologist that may result in inappropriate management of the patient. Uniformity in terminology is desirable so that there is a correlation between the pathologic diagnosis and the clinical import of that diagnosis. In an attempt to standardize the terminology of upper aerodigestive tract intraepithelial lesions using a grading system akin to that of the cervical mucosa, various grading systems have been proposed including squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (SIN I–III)1 laryngeal intraepithelial neoplasia (LIN),5 and the Ljubljana classification6 with the more recent amended Ljubljana classification.7 The forthcoming World Health Organization (WHO) publication of Head and Neck Tumors has proposed a two-tiered (binary) grading system for laryngeal dysplasia 3 as well as oral dysplasia which is applicable for keratinizing and non-keratinizing dysplasia although the former is overwhelmingly the most common dysplastic type especially relative to the larynx and oral cavity. This proposed classification is an adaptation of similar binary classification of uterine cervical dysplasia as well as those of other organs systems (eg, pancreas8) and in the UADT includes: (1) low-grade intraepithelial dysplasia encompassing mild dysplasia and (2) high-grade intraepithelial dysplasia encompassing moderate and severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ. The rationale for this proposal is based on the risk of progression to invasive carcinoma in association with UADT dysplasia. Keratotic epithelium without dysplasia carries a very low risk of developing subsequent carcinoma with reported incidences of from 1 to 5%.1, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 In contrast, keratotic epithelium with dysplasia is associated with an increased risk for the subsequent progression or development of premalignant or overtly carcinomatous changes varying from 11 to 18%1, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 of cases. This risk of malignant transformation represents an increase of from three to five times as compared to carcinoma arising in keratotic lesions without atypia. The potential value in grading keratotic dysplasias is apparent from Barnes’s review of the literature 14 in which the risk for developing invasive carcinoma in mild, moderate and severe dysplasia was 5.7, 22.5 and 28.4%, respectively. This meta-analysis shows no statistical difference in the progression to invasive carcinoma between moderate dysplasia and severe dysplasia justifying subsuming moderate and severe dysplasia into a single high-grade category.

Histopathology of Dysplasia

As previously indicated, the diagnosis of keratinizing dysplasia is often predicated on a combination of architectural and cellular abnormalities (Table 1) including proliferation of immature or ‘uncommitted’ cells with process beginning in basal and parabasal area (Figure 1). Architectural abnormalities include irregular epithelial stratification with elongated rete ridges extending in a downward (bulbous) fashion into submucosa; loss of maturation with increased cellularity in the superficial epithelium (normally in mature squamous epithelium there is a decrease in the cellularity from the basal zone toward the keratinizing layers); crowding of cells with loss of polarity especially in the basal zone but may extend in as much as the whole epithelium; These alterations often occur in the presence of surface keratinization.

Upper aerodigestive tract dysplasia. (a) Low-grade (mild) dysplasia characterized by squamous epithelium with keratosis and associated dysplastic cytologic changes limited in extent and limited to the basal zone including an isolated dyskeratotic cell (arrow) and relatively flat to slightly widened rete ridges. Mitotic figures (arrowheads) are seen near the basal layer; (b) high-grade (moderate to severe) dysplasia characterized by squamous epithelium with keratosis and readily apparent dysplastic cytologic changes involving at least two-thirds of the thickness of the epithelium with relatively flat to slightly widened rete ridges; (c) high-grade (moderate to severe) dysplasia characterized by the presence of markedly elongated and downwardly extending rete ridges with readily apparent dysplastic cytologic changes involving at near complete involvement of the whole epithelium; (d) Paradoxical maturation is characterized by abnormal keratinization and/or keratin pearl formation in the basal zone; foci of invasive carcinoma were seen adjacent to this area. (All images with permission from Wenig BM. Atlas of head and neck pathology, 3rd edition, Elsevier; Philadelphia; 2016).

The cellular abnormalities include abnormal variation in nuclear size (anisonucleosis); abnormnal variation in the nuclear shape (ie, nuclear pleomorphism); increased nuclear size relative to cytoplasm (increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio); nuclear hyperchromasia with irregularities in nuclear contour; prominent nucleoli (not unique to dysplasia and may be seen in a reactive or reparative process); increased mitotic activity, especially away from the basal zone involving the mid- and upper (superficial) portions of the surface epithelium that may include atypical forms; apoptosis and abnormal keratosis (dsykeratosis, paradoxical maturation) occurring in individual cells or with keratin pearls in elongated rete ridges or in basal zone epithelium. In the grading of UADT dysplasia, the presence of surface keratinization is not significant, however, finding dyskeratotic cells, especially when increased in numbers and found throughout the entire epithelium, represents an important clue to the presence of significant dysplasia.

There is little utility in the use of immunohistochemical staining in the diagnosis of keratinizing dysplasias of the UADT. Unlike the uterine cervical dysplasia where p16 and Ki67 immunostaining assists in the diagnosis,4 the same is not true of UADT keratinizing dysplasias. With very few exceptions (see below), human papillomavirus (HPV) is not implicated in the development or progression of UADT keratinizing dysplasia rendering p16 staining essentially useless in most cases.3 Typically, p16 is negative or shows patchy staining even in high-grade keratinizing dysplasia (Figure 2). Further, given the fact that keratinizing high-grade dysplasia have alterations limited to the basal zone (lower third) epithelium with most (>two thirds) of the surface epithelium composed of bland (non-dysplastic) epithelium, there will not be an increase in the proliferation rate in the mid- to upper zone epithelium rendering Ki67 of little to no diagnostic utility (Figure 2).3

There is little utility in using p16 and Ki67 staining in the diagnosis of keratinizing dysplasias of the UADT. (a) p16 is usually negative (or at best shows patchy staining) and (b) increase in the proliferation rate as seen by Ki67 staining is limited to the dysplasia limited to basal zone epithelium.

The role of HPV in the development of intraepithelial dysplasia of the UADT in particular the larynx and oral cavity remains unproven. However, recently the role of HPV in the development of select UADT intraepithelial dysplasias has changed based on findings transcriptionally active HPV in association with a specific type of oral intraepithelial dysplasia.15, 16 In separate published studies, Woo et al15 and McCord et al16 described HPV-associated oral intraepithelial dysplasia characterized by brightly eosinophilic compact ortho- or parakeratosis, epithelial hyperplasia with marked karyorrhexis and apoptosis present throughout the epithelium (Figure 3); surrounding cells with features of conventional dysplasia; and presence of koilocytes. These HPV-associated oral intraepithelial lesions occur mostly in adult men on the ventral or lateral tongue, positive for p16 (Figure 3) and high-risk HPV.15 It should be noted that extensive HPV-related carcinoma in situ of the UADT has been reported in association with non-keratinizing histologic features.17

HPV-associated oral intraepithelial dysplasia. (a, b) This dysplastic lesion is characterized by brightly eosinophilic compact ortho- or parakeratosis, epithelial hyperplasia with marked karyorrhexis and apoptosis present throughout the epithelium and surrounding cells with features of conventional dysplasia; (c) the dysplastic epithelium shows diffuse and strong p16 immunoreactivity while adjacent non-dysplastic epithelium is p16 negative. in situ hybridization confirmation for high-risk HPV is associated with these findings (not shown). (Slides for photography provided by Sook-Bin Woo, DMD).

Microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

Microinvasive SCC (also referred to as superficial or ‘early’ invasive SCC) is a cancer that infiltrates into the superficial compartment of the lamina propria. As simple as this may appear, the diagnosis of superficially invasive SCC can be subjective with no unanimous definition among pathologists. For laryngeal lesions, the most accepted definition for microinvasive carcinoma is the presence of invasive SCC that extends into the stroma no more than 0.5 mm as measured from the adjacent (nonneoplastic) epithelial basement membrane.14 A diagnosis of microinvasive carcinoma excludes those lesions that are restricted to the surface epithelium or carcinoma in situ (Tis) and those carcinomas that are deeply invasive into muscle and cartilage, and extralaryngeal structures (T2 or greater tumors). Also, the presence of lymph-vascular space invasion would exclude a diagnosis of microinvasive carcinoma.14 The clinical manifestations and appearance of microinvasive SCC are similar to those of carcinoma in situ. In the larynx, full cord mobility is present. Any dysfunction in vocal cord mobility (fixation) by definition means muscle invasion, which excludes a diagnosis of microinvasive cancer.

Histologically, microinvasive carcinoma can occur in two unrelated phases. The first is the development from and as a continuum of carcinoma in situ. The second is invasion from an epithelium demonstrating the absence of full thickness intraepithelial dysplasia or CIS. In the upper aerodigestive tract, particularly in the larynx, severe dysplasia (ie, carcinoma in situ) is not a prerequisite for the development of an invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Such invasive carcinomas ‘drop off’ or ‘drop down’ from the basal cell layer with the overlying mucosa showing no evidence of dysplasia (Figure 4). In all examples of invasive carcinoma the invasive nests must be cytologically malignant with dysplastic changes, dyskeratosis and mitotic figures, including atypical forms. The tumor nests have an irregular outline with infiltrative borders. The presence of invasive cancer generally results in stromal induction or a desmoplastic host response that includes edematous change immediately around the tumor nests with granulation tissue and fibrosis. Of note, extension of the dysplastic process to involve the seromucinous glands is still considered as carcinoma in situ and not invasive carcinoma. Keratin granuloma formation is a not infrequent finding in association with extensively invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck in particular with (but not limited to) oral cavity carcinoma. The presence of keratin granuloma formation (Figure 5) is felt to represent presumptive evidence for the presence of invasive squamous cell carcinoma in cases where other foci of invasive carcinoma may not be readily apparent.

Keratin granuloma formation. (a, b) High-grade intraepithelial dysplasia (top, right) without definitive foci of invasive carcinoma. The presence of keratin granuloma formation characterized by submucosal foci of multinucleated giant cells with (arrowhead) and without identifiable eosinophilic keratin material; (c). cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) immunoreactivity confirms the keratin granuloma and is most helpful in example where keratin material is not readily identified by light microscopy. However, in such cases the absence of keratin positive material (and presence of CD68 staining) precludes confirmation of keratin granuloma formation and does not support the possible presence of invasive carcinoma.

Microinvasive cancer is a biologically malignant lesion potentially capable of gaining access to lymphatic or vascular channels in the lamina propria that may result in metastatic disease. For microinvasive carcinoma of the laryngeal glottis, several studies have shown that the clinical significance is similar to CIS/severe dysplasia that with appropriate therapy (excision and/or radiotherapy) progression of disease from a microinvasive to a more invasive carcinoma does not occur. 18, 19, 20, 21 This may be due to the earlier clinical manifestations produced by glottic cancers leading to an earlier diagnosis of cancer before it has invaded into deeper aspects of the larynx. Glottic microinvasive cancers are generally not associated with metastatic disease due to the fact that the glottic portion of the larynx has quantitatively less lymph-vascular spaces as compared to the supra- and subglottis. In contrast to the laryngeal glottis, supraglottic microinvasive carcinomas are associated with metastatic disease in ~20 percent of patients.22

Select variants of squamous cell carcinoma

Papillary (Exophytic) SCC

PSCC represents an uncommon but distinct subtype of head and neck SCC. The demographics for this subtype of SCC are similar to those of conventional SCC with the tendency to affect men more than women, and occurring in adults with a mean age in the 7th decade of life. PSCC predilects to the larynx, oral cavity, oropharynx (tonsil and base of tongue) and hypopharynx, and sinonasal tract.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 The larynx is the most common site of occurrence. Within the larynx most of these carcinomas are located in the supraglottis followed by the glottis and rarely in the subglottis. Laryngeal involvement includes hoarseness and airway obstruction; less often, dysphagia and hemoptysis may occur.

PSCCs usually arise de novo without identification of pre- or coexisting papilloma although association with precursor papilloma or occurrence in patients with previous history of a papilloma at the site of the PSCC have been reported.25 PSCC may be associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) but histology and subsite localization may corroborate whether HPV may be involved. Oropharyngeal PSCCs tend to be non-keratinizing and associated with high-risk HPV;26, 29 laryngeal and oral PSCCs tend to be keratinizing and not associated with HPV although may still harbor transcriptionally active virus.29 Smoking and alcohol have been linked to the development of PSCC.

Papillary SCC is most often seen as a solitary lesion with an exophytic or papillary growth. Tumor size may range from 2 mm up to 4 cm. Histologically, PSCC has filiform growth with finger-like projections and identifiable fibrovascular cores or a broad-based bulbous to exophytic growth with rounded projections resembling a cauliflower-like growth pattern in which fibrovascular cores can be seen but tend to be limited to absent. Two morphologic types of PSCC have been identified including non-keratinizing and keratinizing types. The non-keratinizing type includes papillae completely covered by immature basaloid cells that are cytologically malignant (Figure 6). The presence of malignant epithelium identifies these tumors as carcinomas separating them from papillomas. Surface keratinization is generally limited and often absent. These tumors tend to be p16 positive and p53 negative, and harbor transcriptionally active HPV. The keratinizing type includes intraepithelial cells that show maturation with minimal surface parakeratin (Figure 7). These tumors tend to be p16 negative and p53 positive and tend to lack transcriptionally active virus although some cases may be p16-positive and harbor transcriptionally active HPV.

Laryngeal papillary/exophytic squamous cell carcinoma, non-keratinizing type characterized by; (a) papillary (filiform) to rounded (broad-based bulbous) exophytic growth; (b, c) non-keratinizing high-grade intraepithelial dysplasia involving the entire epithelium (carcinoma in situ); (d) diffuse and strong p16 immunoreactivity.

PSCCs may be entirely in situ (irrespective of size) or show only superficial invasion. The presence of invasion may be difficult to demonstrate in biopsy specimens and multiple biopsies may be required in order to establish the diagnosis. In general, on the basis of the extent of growth with formation of a clinically appreciable exophytic mass going beyond the general concept of an in situ carcinoma, these tumors should be considered as being at least superficially invasive even in the absence of definitive evidence of stromal invasion.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of PSCC includes laryngeal papillomatosis (LP) and verrucous carcinoma (VC). LP is distinguished by its bland epithelial proliferation. Cytologic abnormalities may be seen in LP but they tend to be focal when present but do not approach the level of dysplasia seen in PSCC. VC is characterized by a verrucous growth pattern with marked keratosis in layers or tiers, absent nuclear atypia, absent mitotic activity beyond the basal layer, and a pushing rather than infiltrative pattern of invasion. These features contrast with those seen in PSCC.

Verrucous Carcinoma

VC is a highly differentiated variant of SCC with locally destructive but not metastatic capabilities characterized by exophytic and/or warty appearance, absence of epithelial dysplasia and presence of pushing margins. VC has also been referred to as the Ackerman tumor.33

VC affects men more than women and generally occurs in the 6th and 7th decades of life. VC can occur anywhere in the upper aerodigestive tract. The most common sites of occurrence in descending order include oral cavity, larynx, nasal fossa, sinonasal tract, and nasopharynx.34, 35, 36, 37 Symptoms vary according to site. In the oral cavity, VC present as a mass with or without pain. Hoarseness is the most common complaint relative to laryngeal lesions. Less frequent symptoms include airway obstruction, hemoptysis, dysphagia. Oral cavity verrucous carcinomas most commonly arise on the buccal mucosa and gingiva. The most common site of occurrence in the larynx is the glottic area.

The etiology of VC includes tobacco smoking or chewing. A viral (human papillomavirus [HPV]) causation in the development of VC has not been proven and at present there is no evidence supporting HPV as directly associated with the development of VC.38, 39 The active role of HPV is more likely as a promoter in the multistep process of carcinogenesis in squamous cells of the upper aerodigestive tract. Two viral oncoproteins of high-risk HPVs, E6 and E7, promote tumor progression by inactivating the p53 and retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene products, respectively, thereby disrupting cell-cycle regulatory pathways in the genetic progression to head and neck SCC.40

VC appear as tan or white, warty, fungating or exophytic, firm to hard masses of varying size measuring up to 9-10 cm in diameter. In general, the tumors are attached by a broad base. The histologic appearance of VC is that of a benign-appearing squamous cell proliferation requiring the following characteristics for diagnosis: (1) uniform cells without dysplastic features nor mitoses; (2) marked surface (ortho)keratinization (‘church-spire’ keratosis); (3) broad or bulbous rete pegs with a pushing but not an infiltrative margin (Figure 8). Lichenoid inflammation including mature lymphocytes and plasma cells may be prominent at the interface of the epithelium and submucosa (Figure 9).

Verrucous carcinoma. (a) Low magnification shows an epithelial proliferation with prominent surface verrucoid keratinization (‘church-spire’ keratosis) and downward bulbous appearing rete ridges with extension into the underlying stroma; (b) at higher magnification the rounded rete ridges are composed of cytologically bland appearing epithelial cells lacking dysplasia; mitotic figures (arrowheads) can be seen but are limited to the basal zone area.

Verrucous carcinoma with associated lichenoid inflammation. (a) Low magnification shows an epithelial proliferation with prominent surface verrucoid keratinization (‘church-spire’ keratosis) and downward bulbous appearing rete ridges with extension into the underlying stroma and the presence of inflammation at the interface of the epithelium and submucosa; (b) at higher magnification the rounded rete ridges are composed of cytologically bland appearing epithelial cells lacking dysplasia; within the submucosa there is a mixed chronic inflammation including mature lymphocytes and plasma cells.

The pathologic diagnosis of VC may be extremely difficult requiring multiple biopsies over several years prior to identification of diagnostic features supporting appropriate interpretation. Both clinician and pathologists should be aware of this fact. To this end, adequate biopsy material is critical to interpretation and should include a good epithelial-stromal interface. The pathologist should not over interpret a verrucoid lesion as a carcinoma without seeing the relationship of the more superficial aspects of the lesion to the underlying stroma.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of VC includes reactive keratosis, epithelial hyperplasia and ‘conventional’ squamous cell carcinoma.

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) and verrucous hyperplasia represent interrelated and irreversible mucosal lesions of the oral cavity and upper aerodigestive tract with a propensity to progress to either VC or conventional types of squamous cell carcinoma.41, 42, 43 PVL is a rare aggressive form of oral leukoplakia with a tendency to recur, often with multifocal oral involvement, and to undergo malignant transformation. PVL is most common in elderly women (mean age in the 8th decade of life) with a long history (decades) of oral leukoplakia. PVL most commonly begins on the buccal mucosa followed by the hard and soft palate, alveolar mucosa, tongue, floor of mouth, gingiva and lip. While a history of tobacco use is present in a high percentage of patients (greater than 50%), a significant minority of patients have no history of tobacco use. The diagnosis of PVL in its early stages is virtually impossible due to the innocuous appearance of the lesions. The clinical and pathologic appearance in the early stages of PVL is no different than any other type of leukoplakic lesion. Clinically, the lesion is a flat, thickened keratosis with the histologic appearance of a non-dysplastic keratosis. With progression of disease, the lesions become multiple, multifocal and confluent, with an exophytic and/or warty (verrucoid) appearance. It is in the latter clinical form that squamous cancer (verrucous carcinoma or conventional squamous cell carcinoma) is seen. Any given lesion may show a combination of verrucous hyperplasia, verrucous carcinoma and conventional well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Owing to the absence of defined pathologic lesions, identifying patients with the early diagnosis of PVL is challenging.44 The diagnosis can only be achieved through the clinical observation of the temporal progression in individual patients to verrucous and/or conventional squamous carcinoma.44 Given the fact that PVL is associated with VC in a high percentage of cases, some authors believe that PVL should be considered as a premalignant condition or an early biologic form of VC.41, 45 This would then obviate the confusion, both clinically and pathologically, that surrounds the use of the term verrucous hyperplasia in describing these oral cavity lesions. PVL is composed of hyperplastic squamous epithelium with regularly spaced, verrucous epithelial projections and associated hyperkeratosis. PVL is a sharply defined lesion and in contrast to the downward growth into the underlying submucosal compartment by the bulbous rete ridges in VC, the hyperplastic epithelium in PVL remains superficial (without submucosal invasion) and does not extend deeper than that of the adjacent epithelium. This raises the issue of adequate sampling and the difficulties in differential diagnosis on incisional biopsy material. In order to exclude the presence of submucosal invasion, complete excision of the lesion allowing for histologic examination of the entire lesion is most appropriate.

The differentiation of VC from a ‘conventional’ type of carcinoma is based on the presence or absence of cytologic abnormalities. Dysplastic features limited in scope and confined to the basal zone areas can be seen in verrucous carcinoma. Any dysplastic features greater than this should exclude a diagnosis of VC. Recently, a variant of VC has been described associated with dysplasia or minimal invasion suggesting that dysplasia and/or minimal invasive SCC do not adversely affect outcomes in tumors otherwise showing diagnostic features of VC.45 Hybrid carcinomas are tumors showing mixed histology including foci of VC and foci of conventional squamous cell carcinoma.36, 46 and have been reported in up to 20% of cases.46 Hybrid carcinomas may occur in larynx but more commonly seen in oral cavity lesions. Careful evaluation of the depth of the lesion is important to exclude this possibility. The biologic risk in hybrid carcinomas is that of conventional SCC including potential for metastatic tumor.

Spindle cell squamous carcinoma

SCSC, also referred to as sarcomatoid carcinoma, is a biphasic variant of squamous cell carcinoma composed of conventional squamous cell carcinoma (in situ or invasive carcinoma) associated with a malignant spindle-shaped and pleomorphic (epithelioid) component.

The majority of SCSC occur in men (85%) most frequently in 6th-8th decades of life.47, 48, 49, 50 SCSC can occur anywhere in the upper aerodigestive tract. The most common sites in descending order of occurrence include the larynx (true vocal cords>false vocal cords and supraglottis), oral cavity (lips, tongue, gingiva, floor of mouth, buccal mucosa), skin, tonsil and pharynx. Symptoms vary according to site. Laryngeal SCSC is associated with hoarseness, voice changes, airway obstruction and/or dysphagia.

The development of SCSC has been lined to tobacco use (cigarette smoking).47 SCSC may occur in areas of prior irradiation (radiation-induced carcinoma) following treatment of other mucosal based carcinomas.47, 48, 51 SCSC is not associated with transcriptionally active HPV52 although rarely oropharyngeal cases have been shown to harbor transcriptionally active high-risk HPV.53

Epithelial derivation is supported by the intimate association with conventional squamous cell carcinoma, and the presence of cytokeratin immunoreactivity in the majority of cases. Despite the presence of heterologous elements, including malignant bone or cartilage, neither of these components have been reported to metastasize and in all probability represent a metaplastic phenomenon. Identical immunohistochemical p53 expression patterns in the epithelial and spindle cell components of SCSC supports the concept that these phenotypically divergent cell populations share similar developmental pathways and divests the concept that SCSC represents a reactive process or a collision tumor between epithelial and mesenchymal components.54

SCSC often is a grossly polypoid or fungating mass. Variations in the gross appearance may correlate with the primary site of occurrence: larynx—polypoid or exophytic; sinonasal/nasopharynx—fungating and/or ulcerative. SCSC are firm, tan-white, gray or pink mass varying in size from 1 to 6 cm.

The histologic features that define SCSC include the identification of a malignant undifferentiated spindle cell proliferation and the presence of a conventional squamous cell component. The latter may include high-grade intraepithelial dysplasia and/or frankly invasive differentiated squamous carcinoma (Figure 10). However, not infrequently ulceration of the surface epithelium is present precluding identification of an intraepithelial dysplastic component. The spindle cell component generally is the dominant cell type. The spindle cell proliferation is usually hypercellular and pleomorphic with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and increased mitotic activity (typical and atypical) (Figure 11). Necrosis is not uncommon. A variable amount of stromal collagenization is present varying from minimal to prominent, the latter tending to be less cellular (pauci- to hypocellular) which may be referred to as collagenized (hypocellular) SCSC (Figure 11). Irrespective of the amount of stromal collagenization, is still there nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia with or without increased mitotic activity. The growth pattern varies and includes fascicular, storiform, or palisading; an associated myxomatous stroma may be present. Heterologous elements, including bone and cartilage may be present and may even be malignant (chondrosarcomatous or osteosarcomatous foci).55 Rhabdomyosarcomatous elements may rarely be present characterized by the presence of identifiable rhabdomyoblasts and by immunohistochemical staining including desmin, myogenin (myf4), and myoglobin reactivity.56

Laryngeal spindle cell squamous (sarcomatoid) carcinoma. The histologic findings vary from case to case and may include: (a) ulcerated polypoid lesion focally with intact surface epithelium (arrowheads) and the presence of submucosal cellular proliferation; (b) high-grade intraepithelial dysplasia (middle to top) blending with a malignant spindle-shaped and epithelioid submucosal proliferation; (c) invasive differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in association with a malignant spindle-shaped and epithelioid cellular proliferation; (d) intact non-dysplastic squamous epithelium overlying the dominant submucosal spindle-shaped cellular proliferation with fascicular to storiform growth; (e) neoplasm entirely comprised of a submucosal malignant spindle-shaped and epithelioid cell proliferation with fascicular to storiform growth without an identifiable epithelial cell component.

(a and b) The spindle cell proliferation is usually hypercellular and pleomorphic with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei, increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and the presence of mitotic activity (typical and atypical); a variable degree of stromal fibrosis is present varying from minimal (a) to moderate (b); (c) in this example there is marked stromal collagen deposition is present associated with a less cellular infiltrate which nonetheless includes markedly atypical nuclei characterized by nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia. This example may be referred to as collagenized (hypocellular) SCSC.

The spindle cells are cytokeratin immunoreactive in the majority of cases57, 58, 59, 60, 61 but in up to 40% of cases may be cytokeratin negative.62 Broad spectrum of cytokeratin staining should be used including: pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3), CAM5.2, CK5/6, OSCAR, CK18, and CK903 (Figure 12). Keratin reactivity may vary from focal to diffuse. The absence of cytokeratin staining does not exclude a diagnosis of SCSC. Nuclear p63 and/or p40 immunoreactivity often mirrors cytokeratin reactivity but may be positive in cases lacking cytokeratin staining.62 p63 staining is more consistently positive than p40 but even so may be very limited and present only in scattered malignant cells (Figure 12). Vimentin reactivity consistently identified in all cases and tends to be diffuse and strongly reactive (Figure 12). Various myogenic markers, including desmin and actins may be present.57, 60, 63 Coexpression of mesenchymal markers and epithelial markers (ie, cytokeratin) may occur. In the absence of rhabdomyoblastic differentiation, other myogenic markers including myogenin and myoglobin typically are not present. p16 positivity may be present in a minority of cases and tend to be located in oropharynx.53

In the majority of cases of SCSC there will be immunohistochemical staining for epithelial markers but multiple different types of keratins may be required including: (a) AE1/AE3; (b) CAM5.2; (c) CK5; and (d) OSCAR. It should be noted that in many cases the keratin staining is extremely limited and not as extensively reactive as depicted in these images. Further, in a significant minority of cases cytokeratin staining may be negative. (e) In addition, p63 (and/or p40—not shown) reactivity may present in cases nonreactive for keratins but p63 immunoreactivity may be limited to scattered positive neoplastic cells nuclei (arrowheads); (f) vimentin immunoreactivity is seen in virtually all cases of SCSC tending to be diffuse and strong. Vimentin immunoreactivity in cases devoid of reactivity for any epithelial markers is not diagnostic for a sarcoma even if other purported mesenchymal cell markers (eg, desmin, actins) are positive.

Differential Diagnosis

The differentiated squamous cell component of SCSC may be limited requiring multiple sectioning for identification or it may be absent. The differential diagnosis includes reactive (myo)fibroblastic proliferations, mucosal malignant melanoma and sarcomas

Reactive and neoplastic lesions composed of myofibroblastic cells include nodular fasciitis-like lesions and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMT) and have been reported as occurring in the larynx.64 IMTs are moderately cellular with a proliferation of spindle-shaped cells including enlarged nuclei but with ample basophilic appearing cytoplasm (low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio) and an absence of a striking degree of nuclear pleomorphism. Intranuclear eosinophilic inclusions may be identified. Mitotic figures may be encountered but atypical mitoses are not seen. The findings of atypical mitoses should prompt consideration of a malignancy. IMTs are not encapsulated but they do not exhibit the insidious pattern of infiltration of adjacent tissues which is characteristic of malignant neoplasms such as SCSC. IMTs lack staining for epithelial markers (eg, cytokeratins, p63, and p40). In addition, the myofibroblastic cell component may be muscle specific actin (HHF35), smooth muscle actin, and vimentin positive. IMTs may show the presence of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangements and expression in IMT indicating oncogenic ALK expression as an important mechanism in the pathogenesis of IMT and supports the concept that IMTs are neoplastic.65, 66 The cells of IMT may be ALK1 positive, a feature not identified in SCSC

Sarcomas of the UADT, in particular the larynx, are uncommon. The most common laryngeal sarcoma is chondrosarcoma. In general, sarcomas of the UADT are deeply-seated in any given location and do not usually result in a polypoid mass protruding from a mucosal surface as occurs in SCSC. As a rule, a malignant spindle cell neoplasm of a mucosal surface of the upper aerodigestive tract presenting as a polypoid lesion or identified in more superficial locations of the submucosa should be considered as a SCSC. This is true even in the absence of a differentiated squamous epithelial component and/or the absence of immunoreactivity for epithelial markers.

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma

BSCC is a high-grade variant of SCC histologically characterized by an invasive neoplasm predominantly composed of basaloid appearing cells intimately associated with dysplastic squamous epithelium, in situ squamous cell carcinoma and/or invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

BSCC occurs more commonly in men than in women and predominantly occurs in the sixth–seventh decades of life. BSCC predilect to the hypopharynx (piriform sinus), larynx (supraglottis), and oropharynx (base of tongue, tonsil).67, 68, 69, 70 Symptoms depend on the site of occurrence and include hoarseness, dysphagia, pain, or a neck mass.

BSCC can be subdivided into those associated with HPV (HPV-associated BSCC) and non-HPV-associated BSCC. Oropharyngeal BSCCs tend to be associated with human papillomavirus (HPV)71, 72 but not all of oropharyngeal BSCCs are associated with HPV. The HPV-associated BSCC predilect to base of tongue>tonsil, are more common in men than women; are immunoreactive for p16 and are associated with a better prognosis than non-HPV-associated BSCC. The non-HPV-associated BSCC tend to occur in non-oropharyngeal sites including (but not limited to) the hypopharynx (piriform sinus) and larynx, are more common in men than in women and tend to occur in the sixth–seventh decades of life. The non-HPV-associated BSCC tend to be associated with tobacco and alcohol use.

The cell of origin has not definitively been identified but in all probability is a single totipotential cell capable of divergent differentiation and located either in the basal cell layer of the surface epithelium or within seromucous glands.

Grossly, these tumors are described as firm to hard, tan-white mass often with associated central necrosis measuring up to 6.0 cm in greatest dimension. Infrequently, they may be exophytic in appearance. The histology of BSCC is similar whether associated with or unrelated to HPV. Histologically, BSCC is an invasive neoplasm composed of basaloid cells with an associated squamous component. A variety of growth patterns may be seen, including solid, lobular, cribriform, cords, trabeculae, and gland-like or cystic (Figure 13). Comedonecrosis is seen in the center of the neoplastic lobules. The basaloid cell component is the predominant cell type and consists of cells with pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei, scanty cytoplasm and increased mitotic activity (Figure 13). Peripheral nuclear palisading may be present. Intercellular deposition of a hyalin or mucohyalin material can be seen similar in appearance to the reduplicated basement membrane material that is seen in some salivary gland tumors (Figure 13). Infrequently, an associated spindle cell component may be identified (Figure 13) and true neural-type rosettes may rarely be present.73 The squamous component includes high-grade intraepithelial dysplasia, foci of abrupt keratinization or invasive differentiated squamous cell carcinoma characterized by presence of intercellular bridges, keratin pearl formation and/or individual cell keratinization (cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm; Figure 13). The squamous foci typically represent a minor component and may only be focally present and absent in biopsies. Continuity with the surface epithelium may be seen. BSCC tend to be extensively infiltrative including perineural invasion, lymph-vascular invasion and invasion into soft tissues (eg, skeletal muscle; Figure 14); direct invasion into bone may also be present.

Histologic features of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (BSCC) include: (a) infiltrating cellular neoplasm with lobular and solid growth and foci of comedonecrosis; (b) in some cases, carcinoma in situ may be present in association with invasive keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma as well as invasive nests of basaloid appearing cells with associated extracellular mucinous appearing material; (c). most cases are dominated by a basaloid cell population characterized by nuclear hyperchromasia, marked nuclear pleomorphism and increased mitotic activity with individual cell necrosis and comedotype necrosis; (d) the squamous differentiated component is usually the minor component varying from case to case and may include limited identifiable foci of keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma within (or separate from) the dominant basaloid cell population; (e) extracellular eosinophilic (reduplicated basement membrane-like) material may be present reminiscent of features seen in some salivary gland neoplasms; (f) rarely, a malignant spindle cell component may be present in cases with otherwise typical features diagnostic for BSCC; the spindle cell component is diffusely reactive for cytokeratins and p63/p40 (not shown).

Histochemical stains may show periodic acid-Schiff and alcian blue positive material within the cystic spaces. Immunoreactivity is consistenly present with epithelial markers, including cytokeratins (AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, CK5/6, CK903, and OSCAR), and for p63 and p40 (diffusely and strongly reactivity). Neuroendocrine markers (ie, chromogranin and synaptophysin) usually negative but occasional cases may be positive.74 There may be variable expression for vimentin, NSE, S100 protein, and smooth muscle actin. Staining for CD117 and melanoma markers (eg, HMB-45, melanA, tyrosinase, MITF1, and SOX10) is negative. p16 positive BSCC typically seen in association with oropharyngeal origin.71, 72

Differential Diagnosis

Shallow biopsies may belie the depth and extent of invasion and may not be representative of the lesion leading to erroneous classification. The differential diagnosis of BSCC primarily includes adenoid cystic carcinoma and small cell (undifferentiated) neuroendocrine carcinoma. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is characterized by the presence of a proliferation of basaloid cells with homogenous appearing hyperchromatic nuclei lacking significant pleomorphism and generally devoid of mitotic activity. Furthermore, squamous differentiation is not a component of adenoid cystic carcinoma. MYB-NFIB gene fusion typically present in adenoid cystic carcinoma is absent in BSCC:

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma may be difficult to differentiate from BSCC by light microscopy. This is an important differentiation as small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas are non-surgically treated with radiation and systemic chemotherapy. The keratin reactivity in small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma includes punctate paranculear reactivity which is absent in BSCC. p63 reactivity is consistently seen in BSCC with strong and diffuse staining but tends to be absent to only focally present in neuroendocrine carcinomas. Neuroendocrine markers (eg, chromogranin and synaptophysin) are typically positive in small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and negative in BSCC although Morice and Ferreira74 reported rare examples of BSCC to be reactive with such neuroendocrine markers.

Summary

Premalignant squamous intraepithelial lesions of the upper aerodigestive tract are diagnostic challenging, the grading of which has been fraught with inconsistencies and lack of consensus among pathologists resulting in discrepancy in treatment. The recent decision to reduce the grading of dysplasias of the upper aerodigestive tract to a two-tiered (binary) system that includes low-grade dysplasia (encompassing mild dysplasia) and high-grade dysplasia (encompassing moderate and severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ) will allow for greater consensus among pathologists thereby providing for greater reproducibility and consistency in the diagnosis.

Another potential diagnostic problem in mucosal lesions of the UADT is the identification and diagnosis of microinvasive carcinoma. At present, the most accepted definition for microinvasive carcinoma is the presence of invasive squamous cell carcinoma that extends into the stroma no more than 0.5 mm as measured from the adjacent (nonneoplastic) epithelial basement membrane without lymph-vascular invasion. The identification of microinvasive carcinoma may be extremely challenging in biopsy material and the presence of keratin granuloma formation may be a helpful feature in determining whether invasive carcinoma is present.

In addition to the ‘conventional’ type of squamous cell carcinoma, there are a variety of variants of squamous cell carcinoma with specific clinical and pathologic features. The identification of these variants of squamous cell carcinoma and differentiating them from other lesion/neoplasms may have important therapeutic and prognostic import.

References

Crissman JD, Zarbo RJ . Dysplasia, in situ carcinoma, and progression to invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13 (suppl 1):5–16.

Crissman JD, Gnepp DR, Goodman ML et al. Pre-invasive lesions of the upper aerodigestive tract. Histologic definitions and clinical implications (a symposium). Pathol Annu 1987;22:311–353.

Gale N, Hille J, Jordan R et al, Precursor lesions. Dysplasia In: El-Naggar AK, Grandis JR, Slootweg PJ et al (eds). WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours, 4th edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Lyon, France, 2017 (in press).

Nucci MR, Lee KR, Crum CP Tumors of the female genital tract In: Fletcher CDM (ed.). Diagnostic Histopathology of Tumors 4th edn Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia, 2013, pp 814–871.

Friedmann I, Ferlito A Precursors of squamous cell carcinoma In: Ferlito A (ed.). Neoplasms of the Larynx. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, 1993, pp 97–111.

Gale N, Kambic V, Michaels L et al. The Ljubljana classification: a practical strategy for the diagnosis of laryngeal precancerous lesions. Adv Anat Pathol 2000;4:240–251.

Gale N, Blagus R, El-Mofty SK et al. Evaluation of a new grading system for laryngeal squamous intraepithelial lesions-a proposed unified classification. Histopathology 2014;65:456–464.

Basturk O, Hong SM, Wood LD et al. A revised classification system and recommendations from the baltimore consensus meeting for neoplastic precursor lesions in the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:1730–1741.

Crissman JD . Laryngeal keratosis and subsequent carcinoma. Head Neck Surg 1979;1:386–391.

McGavran MH, Bauer WC, Ogura JH . Isolated laryngeal keratosis: Its relation to carcinoma of the larynx based on clinicopathologic study of 87 consecutive cases with long-term follow-up. Laryngoscope 1960;70:932–951.

Norris CM, Peale AR . Keratosis of the larynx. J Laryngol Otol 1963;77:635–647.

Gabriel CE, Jones DG . Hyperkeratosis ofthe larynx. J Laryngol Otol 1973;87:129–134.

Henry RC . The transformation of laryngeal leukoplakia to cancer. J Laryngol Otol 1979;93:447–459.

Barnes L Diseases of the larynx, hypopharynx and esophagus In: Barnes L (ed.). Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. Marcel Dekker: New York, 2001, pp 127–237.

Woo S-B, Cashman EC, Lerman MA . Human papillomavirus-associated oral intraepithelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol 2013;26:1288–1297.

McCord C, Xu J, Xu W et al. Association of high-risk human papillomavirus infection with oral epithelial dysplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2013;115:549.

Chernock RD, Nussenbaum B, Thorstad WL et al. Extensive HPV-related carcinoma in situ of the upper aerodigestive tract with ‘Nonkeratinizing’ histologic features. Head Neck Pathol 2014;8:322–328.

Miller AH, Fisher HR . Clues to the life history of carcinoma in-situ of the larynx. Laryngoscope 1971;81:1475–1480.

Crissman JD, Zarbo RJ, Drozdowicz S et al. Carcinoma in situ and microinvasive squamous carcinoma of the laryngeal glottis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1988;114:299–307.

Gillis TM, Incze MS, Vaughan CW et al. Natural history and management of keratosis, atypia, carcinoma in situ and microinvasive cancer of the larynx. Am J Surg 1983;146:512–516.

Panwar A, Lindau R 3rd, Wieland A . Management of premalignant lesions of the larynx. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2013;13:1045–1051.

DeSanto LW . Cancer of the supraglottic larynx: a review of 260 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1985;93:705–711.

Crissman JD, Kessis T, Shah KV et al. Squamous papillary neoplasia of the upper aerodigestive tract. Hum Pathol 1988;19:1387–1396.

Thompson LDR, Wenig BM, Heffner DK et al. Exophytic and papillary squmaous cell carcinoma of the larynx: a clinicopathologic series of 104 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;120:718–724.

Suarez PA, Adler-Storthz K, Luna MA et al. Papillary squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Head Neck 2000;22:360–368.

Jo VY, Mills SE, Stoler MH et al. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: frequent association with human papillomavirus infection and invasive carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1720–1724.

Russell JO, Hoschar AP, Scharpf J . Papillary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a clinicopathologic series. Am J Otolaryngol. 2011;32:557–563.

El-Mofty SK . HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma variants in the head and neck. Head Neck Pathol 2012;6 (Suppl 1):S55–S62.

Mehrad M, Carpenter DH, Chernock RD et al. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: clinicopathologic and molecular features with special reference to human papillomavirus. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:1349–1356.

Yang CH, Huang CC, Ko MT et al. Human papillomavirus infection and papillary squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck region. Tumour Biol 2013;34:301–307.

Ding Y, Ma L, Shi L et al. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma of the oral mucosa: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 12 cases and literature review. Ann Diagn Pathol 2013;17:18–21.

Fitzpatrick SG, Neuman AN, Cohen DM et al. Papillary variant of squamous cell carcinoma arising on the gingiva: 61 cases reported from within a larger series of gingival squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol 2013;7:320–326.

Ackerman LV . Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery 1948;23:670–678.

Batsakis JG, Hybels R, Crissman JD et al. The pathology of head and neck tumors: Verrucous carcinoma, part 15. Head Neck Surg 1982;5:29–38.

Ferlito A, Recher G . Ackerman’s tumor (verrucous carcinoma) of the larynx. A clinicopathologic study of 77 cases. Cancer 1980;46:1617–1630.

Medina JE, Dichtel W, Luna MA . Verrucous-squamous carcinomas of the oral cavity. A clinicopathologic study of 104 cases. Arch Otolaryngol 1984;110:437–440.

Walvekar RR, Chaukar DA, Deshpande MS et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity: A clinical and pathological study of 101 cases. Oral Oncol 2009;45:47–51.

del Pino M, Bleeker MC, Quint WG et al. Comprehensive analysis of human papillomavirus prevalence and the potential role of low-risk types in verrucous carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2012;25:1354–1363.

Odar K, Kocjan BJ, Hošnjak L et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the head and neck - not a human papillomavirus-related tumour? J Cell Mol Med 2014;18:635–645.

Dyson N, Howley PM, Münger K et al. The human papillomavirus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind the retinoblastoma gene product. Science 1989;243:934–937.

Shear M, Pindborg JJ . Verrucous hyperplasia of the oral mucosa. Cancer 1980;46:1855–1862.

Hansen LS, Olson JA, Silverman S . Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. A long-term study of thirty patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1985;60:285–298.

Murrah VA, Batsakis JG . Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and verrucous hyperplasia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1994;103:660–663.

Gillenwater AM, Vigneswaran N, Fatani H et al. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL): a review of an elusive pathologic entity!. Adv Anat Pathol 2013;20:416–423.

Batsakis JG, Suarez P, el-Naggar AK . Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and its related lesions. Oral Oncol 1999;35:354–359.

Patel KR, Chernock RD, Zhang TR et al. Verrucous carcinomas of the head and neck, including those with associated squamous cell carcinoma, lack transcriptionally active high-risk human papillomavirus. Hum Pathol 2013;44:2385–2392.

Leventon GS, Evans HL . Sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma of the mucous membranes of the head and neck: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Cancer 1981;48:994–1003.

Thompson LD, Wieneke JA, Miettinen M et al. Spindle cell (sarcomatoid) carcinomas of the larynx: a clinicopathologic study of 187 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:153–170.

Viswanathan S, Rahman K, Pallavi S et al. Sarcomatoid (spindle cell) carcinoma of the head and neck mucosal region: a clinicopathologic review of 103 cases from a tertiary referral cancer centre. Head Neck Pathol 2010;4:265–275.

Gerry D, Fritsch VA, Lentsch EJ . Spindle Cell Carcinoma of the Upper Aerodigestive Tract: An analysis of 341 cases with comparison to Conventional Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2014;123:576–583.

Lasser KH, Naeim F, Higgins J et al. “Pseudosarcoma” of the larynx. Am J Surg Pathol 1979;3:397–404.

Larsen ET, Duggan MA, Inoue M . Absence of human papilloma virus DNA in oropharyngeal spindle-cell squamous carcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol 1994;101:514–518.

Watson RF, Chernock RD, Wang X et al. Spindle cell carcinomas of the head and neck rarely harbor transcriptionally-active human papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol 2013;7:250–257.

Ansari-Lari MA, Hoque MO, Califano J et al. Immunohistochemical p53 expression patterns in sarcomatoid carcinomas of the upper respiratory tract. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1024–1031.

Marioni G, Altavilla G, Marino F et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx with osteosarcoma-like stromal metaplasia. Acta Otolaryngol 2004;124:870–873.

Roy S, Purgina B, Seethala RR . Spindle cell carcinoma of the larynx with rhabdomyoblastic heterologous element: a rare form of divergent differentiation. Head Neck Pathol 2013;7:263–267.

Ellis G, Langloss JM, Enzinger FM . Coexpression of keratin and desmin in a carcinosarcoma involving the maxillary alveolar ridge. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1985;60:410–416.

Zarbo RJ, Crissman JD, Venkat H et al. Spindle-cell carcinoma of the aerodigestive tract mucosa: an immunohistologic and ultrastructural study of 18 biphasic tumors and comparison with seven monophasic spindle-cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1986;10:741–753.

Ellis GL, Langloss JM, Heffner DK et al. Spindle-cell carcinoma of the aerodigestive tract: an immunohistochemical analysis of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1987;11:335–342.

Ophir D, Marshak G, Czernobilsky B . Distinctive immunohistochemical labeling of epithelial and mesenchymal elements in laryngeal pseudosarcoma. Laryngoscope 1987;97:490–494.

Lewis JE, Olsen KD, Sebo TJ . Spindle cell carcinoma of the larynx: review of 26 cases including DNA content and immunohistochemistry. Hum Pathol 1997;28:664–673.

Bishop JA, Montgomery EA, Westra WH . Use of p40 and p63 immunohistochemistry and human papillomavirus testing as ancillary tools for the recognition of head and neck sarcomatoid carcinoma and its distinction from benign and malignant mesenchymal processes. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:257–264.

Nakleh RE, Zarbo RJ, Ewing S et al. Myogenic differentiation in spindle cell (sarcomatoid) carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract. Appl Immunohistochem 1993;1:58–68.

Wenig BM, Devaney K, Bisceglia M . Inflammatory myofibroblastic pseudotumors of the larynx: A clinicopathologic report of eight cases including immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Cancer 1995;76:2217–2229.

Lawrence B, Perez-Atayde A, Hibbard MK et al. TPM3-ALK and TPM4-ALK oncogenes in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Am J Pathol 2000;157:377–384.

Coffin CM, Patel A, Perkins S et al. ALK and p80 expression and chromosomal rearrangements involving 2p23 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT). Mod Pathol 2001;14:569–576.

Wain SL, Kier R, Vollmer RT et al. Basaloid-squamous carcinoma of the tongue, hypopharynx and larynx. Hum Pathol 1986;17:1158–1166.

Banks ER, Frierson HF Jr, Mills SE et al. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 40 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:939–946.

Ereño C, Gaafar A, Garmendia M et al. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a clinicopathological and follow-up study of 40 cases and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol 2008;2:83–91.

Fritsch VA, Lentsch EJ . Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: an analysis of 650 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;148:611–618.

Begum S, Westra WH . Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is a mixed variant that can be further resolved by HPV status. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1044–1050.

Chernock RD, Lewis JS Jr, Zhang Q et al. Human papillomavirus-positive basaloid squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract: a distinct clinicopathologic and molecular subtype of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2010;41:1016–1023.

Weineke J, Thompson LDR, Wenig BM . Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Cancer 1999;85:841–854.

Morice WG, Ferreiro JA . Distinction of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma from adenoid cystic and small cell undifferentiated carcinoma by immunohistochemistry. Hum Pathol 1998;29:609–612.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wenig, B. Squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: dysplasia and select variants. Mod Pathol 30 (Suppl 1), S112–S118 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.207

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.207

This article is cited by

-

Two oral verrucous carcinomas in a patient with oral graft vs. host disease– recurrent verrucous carcinoma: a case report

BMC Oral Health (2025)

-

Clinico-tomographic-pathological correlation in nodulo-ulcerative ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a study of 16 cases

International Ophthalmology (2025)

-

Application of artificial intelligence in oral potentially malignant disorders: current opinions and future barriers

Clinical and Translational Oncology (2025)

-

Aldh2 and the tumor suppressor Trp53 play important roles in alcohol-induced squamous field cancerization

Journal of Gastroenterology (2025)

-

Immunophenotypic and Gene Expression Analyses of the Inflammatory Microenvironment in High-Grade Oral Epithelial Dysplasia and Oral Lichen Planus

Head and Neck Pathology (2024)