Abstract

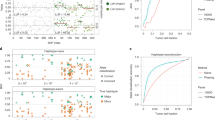

Genomic analysis provides insights into the role of copy number variation in disease, but most methods are not designed to resolve mixed populations of cells. In tumours, where genetic heterogeneity is common1,2,3, very important information may be lost that would be useful for reconstructing evolutionary history. Here we show that with flow-sorted nuclei, whole genome amplification and next generation sequencing we can accurately quantify genomic copy number within an individual nucleus. We apply single-nucleus sequencing to investigate tumour population structure and evolution in two human breast cancer cases. Analysis of 100 single cells from a polygenomic tumour revealed three distinct clonal subpopulations that probably represent sequential clonal expansions. Additional analysis of 100 single cells from a monogenomic primary tumour and its liver metastasis indicated that a single clonal expansion formed the primary tumour and seeded the metastasis. In both primary tumours, we also identified an unexpectedly abundant subpopulation of genetically diverse ‘pseudodiploid’ cells that do not travel to the metastatic site. In contrast to gradual models of tumour progression, our data indicate that tumours grow by punctuated clonal expansions with few persistent intermediates.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Accession codes

Primary accessions

Sequence Read Archive

Data deposits

All data has been deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession number SRA018951.105.

References

Park, S. Y., Gonen, M., Kim, H. J., Michor, F. & Polyak, K. Cellular and genetic diversity in the progression of in situ human breast carcinomas to an invasive phenotype. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 636–644 (2010)

Torres, L. et al. Intratumor genomic heterogeneity in breast cancer with clonal divergence between primary carcinomas and lymph node metastases. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 102, 143–155 (2007)

Farabegoli, F. et al. Clone heterogeneity in diploid and aneuploid breast carcinomas as detected by FISH. Cytometry 46, 50–56 (2001)

Chiang, D. Y. et al. High-resolution mapping of copy-number alterations with massively parallel sequencing. Nature Methods 6, 99–103 (2009)

Yoon, S., Xuan, Z., Makarov, V., Ye, K. & Sebat, J. Sensitive and accurate detection of copy number variants using read depth of coverage. Genome Res. 19, 1586–1592 (2009)

Alkan, C. et al. Personalized copy number and segmental duplication maps using next-generation sequencing. Nature Genet. 41, 1061–1067 (2009)

Geigl, J. B. et al. Identification of small gains and losses in single cells after whole genome amplification on tiling oligo arrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, e105 (2009)

Fuhrmann, C. et al. High-resolution array comparative genomic hybridization of single micrometastatic tumor cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, e39 (2008)

Pugh, T. J. et al. Impact of whole genome amplification on analysis of copy number variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, e80 (2008)

Talseth-Palmer, B. A., Bowden, N. A., Hill, A., Meldrum, C. & Scott, R. J. Whole genome amplification and its impact on CGH array profiles. BMC Res. Notes 1, 56 (2008)

Hughes, S. et al. Use of whole genome amplification and comparative genomic hybridisation to detect chromosomal copy number alterations in cell line material and tumour tissue. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 105, 18–24 (2004)

Huang, J., Pang, J., Watanabe, T., Ng, H. K. & Ohgaki, H. Whole genome amplification for array comparative genomic hybridization using DNA extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded histological sections. J. Mol. Diagn. 11, 109–116 (2009)

Navin, N. et al. Inferring tumor progression from genomic heterogeneity. Genome Res. 20, 68–80 (2010)

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987)

Hicks, J. et al. Novel patterns of genome rearrangement and their association with survival in breast cancer. Genome Res. 16, 1465–1479 (2006)

Prelic, A. et al. A systematic comparison and evaluation of biclustering methods for gene expression data. Bioinformatics 22, 1122–1129 (2006)

Liu, W. et al. Copy number analysis indicates monoclonal origin of lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Nature Med. 15, 559–565 (2009)

Ding, L. et al. Genome remodelling in a basal-like breast cancer metastasis and xenograft. Nature 464, 999–1005 (2010)

Yachida, S. et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature 467, 1114–1117 (2010)

Nowell, P. C. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science 194, 23–28 (1976)

Loeb, L. A., Springgate, C. F. & Battula, N. Errors in DNA replication as a basis of malignant changes. Cancer Res. 34, 2311–2321 (1974)

Bielas, J. H., Loeb, K. R., Rubin, B. P., True, L. D. & Loeb, L. A. Human cancers express a mutator phenotype. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 18238–18242 (2006)

Heng, H. H. et al. Stochastic cancer progression driven by non-clonal chromosome aberrations. J. Cell. Physiol. 208, 461–472 (2006)

Gould, S. J. & Eldredge, N. Punctuated equilibria comes of age. Nature 366, 223–227 (1993)

Langmead, B., Trapnell, C., Pop, M. & Salzberg, S. L. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25 (2009)

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Ronemus, T. Spencer, A. Leotta, J. Meth, M. Kramer, L. Gelley, E. Ghiban. We also thank P. Blake and N. Navin at Sophic Systems Alliance. This work was supported by the NCI T32 Fellowship to N.N., and grants to M.W. and J.H. from the Department of the Army (W81XWH04-1-0477), the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the Simons Foundation. M.W. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.N. designed and performed experiments and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. J.K., A.K., L.M., D.L. and P.A. developed analysis programs. J.T., L.R., K.C., J.M., D.E. and A.S. performed experiments. W.R.M. designed experiments. J.H. and M.W. designed experiments, performed analysis and wrote manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Figures 1-8 with legends and Supplementary Methods. (PDF 4792 kb)

Supplementary Table 1

This table shows a summary of 100 Single Cells in the Polygenomic Tumor T10. (XLS 42 kb)

Supplementary Table 2

This table shows a summary of 100 Single Cells in T16P and T16M Metastatic Tumor Pair. (XLS 45 kb)

Supplementary Table 3

This table shows LOH and Copy Number in Tumor Subpopulations. (XLS 28 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Navin, N., Kendall, J., Troge, J. et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature 472, 90–94 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09807

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09807

This article is cited by

-

scAbsolute: measuring single-cell ploidy and replication status

Genome Biology (2024)

-

Inferring single-cell copy number profiles through cross-cell segmentation of read counts

BMC Genomics (2024)

-

Single-cell lineage tracing with endogenous markers

Biophysical Reviews (2024)

-

Integrative multi-region molecular profiling of primary prostate cancer in men with synchronous lymph node metastasis

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Applications of lung cancer organoids in precision medicine: from bench to bedside

Cell Communication and Signaling (2023)

Steven Horne

Using a single-cell sequencing platform, this report demonstrated that cancer evolution is the result of punctuated clonal expansions with few persistent intermediates(1). This is a significant contribution that illustrates both the power of single-cell sequencing and, in particular, the long-ignored stochastic and discontinuous pattern of somatic cell evolution.

Cancer is a process of somatic evolution(2,3), however, the pattern of cancer evolution remains unclear. Many believe that it is a stepwise evolutionary process where mutations accumulate over time(4). Assuming this is true, drivers of the process should be identifiable and targetable. However, this linear model failed to identify ?magic bullet? cancer genes and cannot explain the diverse karyotypes associated with most cancers. This timely report not only offers insight of this heterogeneity at the single cell level, but also reinforces many previous findings on the patterns of cancer evolution. Some important issues need to be further discussed, however.

First, the evolutionary pattern of cancer at the genome level is far more punctuated than at the gene copy level as the same clonal DNA sequence (building material) can be shuffled and packaged to form a variety of non-clonal genomes (karyotypic architectures)(5). In other words, clonal expansion is often observed at the gene level but not at the genome level. By watching evolution in action, we traced the karyotypic evolution of cancer using in vitro immortalization models of human and mouse cells using multiple-color spectral karyotyping(6). To our surprise, we have observed two phases of cancer evolution, namely a stochastic discontinuous (punctuated) phase where there are no persistent intermediates and a Darwinian stepwise phase where intermediates can easily be identified(7,8). During the punctuated phase, non-clonal chromosomal aberrations (NCCAs) dominate, and the majority of cells display different karyotypes, indicating increased genome heterogeneity. In contrast, during the stepwise phase clonal chromosomal aberrations (CCAs) dominate, with the majority of cells sharing similar karyotypes. Interestingly, there are multiple cycles of NCCA/CCA dynamics during the cancer evolutionary process. We have further linked the punctuated phase with macro-cellular evolution (genome alterations create new systems) and the stepwise phase with micro-cellular evolution (gene mutations modify existing systems)(9). We concluded that punctuated cancer evolution represents a common pattern for cancer evolution and predicted that similar patterns would be identified at gene levels(10). The present report supports the concept of punctuated cancer evolution, which questions the current strategies of treating cancer as a process of linear stepwise evolution. For instance, are cancer genome sequencing projects, which have and will continue to generate diverse data sets rather than common patterns of mutations, of clinical utility(11)?

Second, since cancer evolution consists of macro- (i.e., genome alterations) and micro-evolution (i.e., gene level changes), the somatic evolutionary tree should reflect such differences. It has been demonstrated that the frequencies of structural NCCAs (e.g., stochastic translocated chromosomes) are more influential than numerical NCCAs (e.g., aneuploidy) for tumorigenicity(12). This factor should also be considered when constructing a somatic evolutionary tree.

Third, we would like to correct a minor point. The authors misquoted the mutator phenotype and stochastic progression models as being gradual models of cancer evolution. In fact, the mutator phenotype model aims to explain the mechanism behind the high mutation rates in cancer without favoring the stepwise model(13), while the stochastic model introduced the punctuated model for somatic cell evolution(6). We have been actively promoting the stochastic punctuated model for years(2,8).

Lastly, higher resolution images of bin counts and copy number profiles of single cell representatives of major aneuploidy subpopulations HT16P-A and T16M-A are needed (Fig. 4e in ref. 1). Current images appear to be identical, and some variance is expected by chance alone.

Steven D. Horne, Joshua B. Stevens Ph.D., Batoul Y. Abdallah, Henry H.Q. Heng Ph.D.

References

1. Navin, N. et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature 472,

90-94 (2011).

2. Heng, H.H. et al. The evolutionary mechanism of cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 109,

1072-1084 (2010).

3. Goymer, P. Natural selection: the evolution of cancer. Nature 454, 1046-1048

(2008).

4. Nowell, P.C. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science 194, 23-28

(1976).

5. Heng, H.H. et al. Decoding the genome beyond sequencing: the new phase of

genomic research. Genomics article in press. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.05.008 (2011).

6. Heng, H.H. et al. Stochastic cancer progression driven by non-clonal chromosome

aberrations. J. Cell. Physiol. 208, 461-472 (2006).

7. Gould, S.J., Eldredge, N. Punctuated equilibrium comes of age. Nature 366, 223-

227 (1993).

8. Heng, H.H. Elimination of altered karyotypes by sexual reproduction preserves

species identity. Genome 50, 517-524 (2007).

9. Heng, H.H. The genome-centric concept: resynthesis of evolutionary theory.

BioEssays 31, 512-525 (2009).

10. Ye, C.J., Liu, G., Bremer, S.W. & Heng, H.H. The dynamics of cancer chromosomes

and genomes. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 118, 237-246 (2007).

11. Heng, H.H. Cancer genome sequencing: the challenges ahead. Bioessays 29,

783-794 (2007).

12. Ye, C.J. et al. Genome based cell population heterogeneity promotes

tumorigenicity: the evolutionary mechanism of cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 219, 288-300 (2009).

13. Bielas, J.H., Loeb, K.R., Rubin, B.P., True, L.D. & Loeb, L.A. Human cancers

express a mutator phenotype. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 18238-18242 (2006).