Abstract

The amount of ice present in clouds can affect cloud lifetime, precipitation and radiative properties1,2. The formation of ice in clouds is facilitated by the presence of airborne ice-nucleating particles1,2. Sea spray is one of the major global sources of atmospheric particles, but it is unclear to what extent these particles are capable of nucleating ice3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Sea-spray aerosol contains large amounts of organic material that is ejected into the atmosphere during bubble bursting at the organically enriched sea–air interface or sea surface microlayer12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Here we show that organic material in the sea surface microlayer nucleates ice under conditions relevant for mixed-phase cloud and high-altitude ice cloud formation. The ice-nucleating material is probably biogenic and less than approximately 0.2 micrometres in size. We find that exudates separated from cells of the marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana nucleate ice, and propose that organic material associated with phytoplankton cell exudates is a likely candidate for the observed ice-nucleating ability of the microlayer samples. Global model simulations of marine organic aerosol, in combination with our measurements, suggest that marine organic material may be an important source of ice-nucleating particles in remote marine environments such as the Southern Ocean, North Pacific Ocean and North Atlantic Ocean.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hoose, C. & Möhler, O. Heterogeneous ice nucleation on atmospheric aerosols: a review of results from laboratory experiments. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 9817–9854 (2012)

Murray, B. J., O’Sullivan, D., Atkinson, J. D. & Webb, M. E. Ice nucleation by particles immersed in supercooled cloud droplets. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6519–6554 (2012)

Bigg, E. K. Ice nucleus concentrations in remote areas. J. Atmos. Sci. 30, 1153–1157 (1973)

Rosinski, J., Haagenson, P. L., Nagamoto, C. T. & Parungo, F. Nature of ice-forming nuclei in marine air masses. J. Aerosol Sci. 18, 291–309 (1987)

Bigg, E. K. Ice forming nuclei in the high Arctic. Tellus B48, 223–233 (1996)

Knopf, D. A., Alpert, P. A., Wang, B. & Aller, J. Y. Stimulation of ice nucleation by marine diatoms. Nature Geosci. 4, 88–90 (2011)

Fall, R. & Schnell, R. C. Association of an ice-nucleating psuedomonad with cultures of the marine dinoflagellate, Heterocapsa niei . J. Mar. Res. 43, 257–265 (1985)

Prather, K. A. et al. Bringing the ocean into the laboratory to probe the chemical complexity of sea spray aerosol. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 7550–7555 (2013)

Yun, Y. & Penner, J. E. An evaluation of the potential radiative forcing and climatic impact of marine organic aerosols as heterogeneous ice nuclei. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 4121–4126 (2013)

Burrows, S. M., Hoose, C., Pöschl, U. & Lawrence, M. G. Ice nuclei in marine air: biogenic particles or dust? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 245–267 (2013)

Wang, X. et al. Microbial control of sea spray aerosol composition: a tale of two blooms. ACS Cent. Sci. 1, 124–131 (2015)

Gantt, B. & Meskhidze, N. The physical and chemical characteristics of marine primary organic aerosol: a review. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 3979–3996 (2013)

Aller, J. Y., Kuznetsova, M. R., Jahns, C. J. & Kemp, P. F. The sea surface microlayer as a source of viral and bacterial enrichment in marine aerosols. J. Aerosol Sci. 36, 801–812 (2005)

Orellana, M. V. et al. Marine microgels as a source of cloud condensation nuclei in the high Arctic. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13612–13617 (2011)

Schmitt-Kopplin, P. et al. Dissolved organic matter in sea spray: a transfer study from marine surface water to aerosols. Biogeosciences 9, 1571–1582 (2012)

Russell, L. M., Hawkins, L. N., Frossard, A. A., Quinn, P. K. & Bates, T. S. Carbohydrate-like composition of submicron atmospheric particles and their production from ocean bubble bursting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 6652–6657 (2010)

Leck, C. & Bigg, E. K. Biogenic particles in the surface microlayer and overlaying atmosphere in the central Arctic Ocean during summer. Tellus B57, 305–316 (2005)

Cunliffe, M. et al. Sea surface microlayers: a unified physicochemical and biological perspective of the air–ocean interface. Prog. Oceanogr. 109, 104–116 (2013)

Quinn, P. K. et al. Contribution of sea surface carbon pool to organic matter enrichment in sea spray aerosol. Nature Geosci. 7, 228–232 (2014)

Cziczo, D. J. et al. Clarifying the dominant sources and mechanisms of cirrus cloud formation. Science 340, 1320–1324 (2013)

Yakobi-Hancock, J. D., Ladino, L. A. & Abbatt, J. P. D. Feldspar minerals as efficient deposition ice nuclei. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 11175–11185 (2013)

Kanji, Z. A., Welti, A., Chou, C., Stetzer, O. & Lohmann, U. Laboratory studies of immersion and deposition mode ice nucleation of ozone aged mineral dust particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 9097–9118 (2013)

Pummer, B. G., Bauer, H., Bernardi, J., Bleicher, S. & Grothe, H. Suspendable macromolecules are responsible for ice nucleation activity of birch and conifer pollen. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 2541–2550 (2012)

Augustin, S. et al. Immersion freezing of birch pollen washing water. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 10989–11003 (2013)

O’Sullivan, D. et al. The relevance of nanoscale biological fragments for ice nucleation in clouds. Sci. Rep. 5, 8082 (2015)

Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J. et al. Ice nucleation activity in the widespread soil fungus Mortierella alpina . Biogeosciences 12, 1057–1071 (2015)

Armbrust, E. V. The life of diatoms in the world’s oceans. Nature 459, 185–192 (2009)

Alvain, S., Moulin, C., Dandonneau, Y. & Loisel, H. Seasonal distribution and succession of dominant phytoplankton groups in the global ocean: a satellite view. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 22, GB3001 (2008)

Fuentes, E., Coe, H., Green, D. & McFiggans, G. On the impacts of phytoplankton-derived organic matter on the properties of the primary marine aerosol—part 2: composition, hygroscopicity and cloud condensation activity. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 2585–2602 (2011)

Atkinson, J. D. et al. The importance of feldspar for ice nucleation by mineral dust in mixed-phase clouds. Nature 498, 355–358 (2013)

Koop, T., Luo, B., Tsias, A. & Peter, T. Water activity as the determinant for homogeneous ice nucleation in aqueous solutions. Nature 406, 611–614 (2000)

Alpert, P. A., Aller, J. Y. & Knopf, D. A. Ice nucleation from aqueous NaCl droplets with and without marine diatoms. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 5539–5555 (2011)

Knulst, J. C., Rosenberger, D., Thompson, B. & Paatero, J. Intensive sea surface microlayer investigations of open leads in the pack ice during Arctic Ocean 2001 expedition. Langmuir 19, 10194–10199 (2003)

Wurl, O., Miller, L., Röttgers, R. & Vagle, S. The distribution and fate of surface-active substances in the sea-surface microlayer and water column. Mar. Chem. 115, 1–9 (2009)

Whale, T. F. et al. A technique for quantifying heterogeneous ice nucleation in microlitre supercooled water droplets. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 2437–2447 (2015)

Kanji, Z. A. & Abbatt, J. P. D. The University of Toronto Continuous Flow Diffusion Chamber (UT-CFDC): a simple design for ice nucleation studies. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 43, 730–738 (2009)

Guillard, R. R. L. & Ryther, J. H. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (cleve) Gran. Can. J. Microbiol. 8, 229–239 (1962)

Fisher, N. S. & Wente, M. The release of trace elements by dying marine phytoplankton. Deep-Sea Res. I 40, 671–694 (1993).

Alpert, P. A., Aller, J. Y. & Knopf, D. A. Initiation of the ice phase by marine biogenic surfaces in supersaturated gas and supercooled aqueous phases. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 19882–19894 (2011)

Koop, T. & Zobrist, B. Parameterizations for ice nucleation in biological and atmospheric systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 11, 10839–10850 (2009)

Vali, G. Quantitative evaluation of experimental results an the heterogeneous freezing nucleation of supercooled liquids. J. Atmos. Sci. 28, 402–409 (1971)

Murray, B. J. et al. Kinetics of the homogeneous freezing of water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 10380–10387 (2010)

Kilcoyne, A. L. D. et al. Interferometer-controlled scanning transmission X-ray microscopes at the Advanced Light Source. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 10, 125–136 (2003)

Ghorai, S., Laskin, A. & Tivanski, A. V. Spectroscopic evidence of keto-enol tautomerism in deliquesced malonic acid particles. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 4373–4380 (2011)

Ghorai, S. & Tivanski, A. V. Hygroscopic behavior of individual submicrometer particles studied by X-ray spectromicroscopy. Anal. Chem. 82, 9289–9298 (2010)

Moffet, R. C., Henn, T., Laskin, A. & Gilles, M. K. Automated chemical analysis of internally mixed aerosol particles using X-ray spectromicroscopy at the carbon K-edge. Anal. Chem. 82, 7906–7914 (2010)

Moffet, R. C. & Tivanski, A. V & Gilles, M. K. in Fundamentals and Applications of Aerosol Spectroscopy (eds Signorell, R. & Reid, J. P. ) 419–462 (Taylor & Francis Group, 2010)

Hopkins, R. J., Tivanski, A. V., Marten, B. D. & Gilles, M. K. Chemical bonding and structure of black carbon reference materials and individual carbonaceous atmospheric aerosols. J. Aerosol Sci. 38, 573–591 (2007)

Knopf, D. A. et al. Microspectroscopic imaging and characterization of individually identified ice nucleating particles from a case field study. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 119, 10365–10381 (2014)

Takahama, S., Gilardoni, S., Russell, L. M. & Kilcoyne, A. L. D. Classification of multiple types of organic carbon composition in atmospheric particles by scanning transmission X-ray microscopy analysis. Atmos. Environ. 41, 9435–9451 (2007)

Abramson, L., Wirick, S., Lee, C., Jacobsen, C. & Brandes, J. A. The use of soft X-ray spectromicroscopy to investigate the distribution and composition of organic matter in a diatom frustule and a biomimetic analog. Deep-Sea Res. II 56, 1369–1380 (2009)

Hawkins, L. N. & Russell, L. M. Polysaccharides, proteins, and phytoplankton fragments: four chemically distinct types of marine primary organic aerosol classified by single particle spectromicroscopy. Adv. Meteorol. 2010, 612132 (2010)

Ault, A. P. et al. Size-dependent changes in sea spray aerosol composition and properties with different seawater conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 5603–5612 (2013)

Zubavichus, Y., Shaporenko, A., Grunze, M. & Zharnikov, M. Innershell absorption spectroscopy of amino acids at all relevant absorption edges. J. Phys. Chem. A 109, 6998–7000 (2005)

Brown, M. R. The amino-acid and sugar composition of 16 species of microalgae used in mariculture. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 145, 79–99 (1991)

Kuznetsova, M., Lee, C. & Aller, J. Characterization of the proteinaceous matter in marine aerosols. Mar. Chem. 96, 359–377 (2005)

van Pinxteren, M., Müller, C., Iinuma, Y., Stolle, C. & Herrmann, H. Chemical characterization of dissolved organic compounds from coastal sea surface microlayers (Baltic Sea, Germany). Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 10455–10462 (2012)

Verdugo, P. Marine microgels. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 4, 375–400 (2012)

Brandes, J. A. et al. Examining marine particulate organic matter at sub-micron scales using scanning transmission X-ray microscopy and carbon X-ray absorption near edge structure spectroscopy. Mar. Chem. 92, 107–121 (2004)

Lawrence, J. R. et al. Scanning transmission X-ray, laser scanning, and transmission electron microscopy mapping of the exopolymeric matrix of microbial biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 5543–5554 (2003)

Marie, D., Partensky, F., Jacquet, S. & Vaulot, D. Enumeration and cell cycle analysis of natural populations of marine picoplankton by flow cytometry using the nucleic acid stain SYBR Green I. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 186–193 (1997)

Zubkov, M. V., Burkill, P. H. & Topping, J. N. Flow cytometric enumeration of DNA-stained oceanic planktonic protists. J. Plankton Res. 29, 79–86 (2007)

Engel, A. in Practical Guidelines for the Analysis of Seawater (ed. Wurl, O. ) 125–142 (CRC Press, 2009)

Engel, A. Distribution of transparent exopolymer particles (TEP) in the northeast Atlantic Ocean and their potential significance for aggregation processes. Deep-Sea Res. I 51, 83–92 (2004)

Wurl, O. & Sin, T. in Practical Guidelines for the Analysis of Seawater (ed. Wurl, O. ) 33–48 (CRC Press, 2009)

Pan, X. et al. Dissolved organic carbon and apparent oxygen utilization in the Atlantic Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. I 85, 80–87 (2014)

MacGilchrist, G. A. et al. Effect of enhanced pCO2 levels on the production of dissolved organic carbon and transparent exopolymer particles in short-term bioassay experiments. Biogeosciences 11, 3695–3706 (2014)

Vignati, E. et al. Global scale emission and distribution of sea-spray aerosol: sea-salt and organic enrichment. Atmos. Environ. 44, 670–677 (2010)

Sciare, J. et al. Long-term observations of carbonaceous aerosols in the Austral Ocean atmosphere: Evidence of a biogenic marine organic source. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 114, D15302 (2009)

Mann, G. W. et al. Description and evaluation of GLOMAP-mode: a modal global aerosol microphysics model for the UKCA composition-climate model. Geosci. Model Dev. 3, 519–551 (2010)

Huneeus, N. et al. Global dust model intercomparison in AeroCom phase I. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 7781–7816 (2011)

Nickovic, S., Vukovic, A., Vujadinovic, M., Djurdjevic, V. & Pejanovic, G. Technical note: high-resolution mineralogical database of dust-productive soils for atmospheric dust modeling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 845–855 (2012)

Acknowledgements

T.W.W., B.J.M. and T.F.W. acknowledge the assistance provided by the crew and other scientists onboard the R/V Knorr and the RRS James Clark Ross, the British Antarctic Survey, K. Baustian, J. McQuaid, A. Windross, J. Knulst, J. F. Wilson, A. M. Booth, R. Chance, L. J. Carpenter, S. Peppe, D. O’Sullivan, N. Umo, I. Cotton, H. Pearce, H. Price and M. J. Callaghan. The STXM/NEXAFS analysis was performed at the Advanced Light Source (ALS), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the US Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231 (user award to D.A.K./J.Y.A. ALS-05955). STXM analyses were facilitated by A. L. D. Kilcoyne and M. K. Gilles. L.A.L. acknowledges assistance from R. Leaitch, E. Mungall, R. Christensen and J. Li, and the Pacific region Department of Fisheries and Oceans staff. The Marine Boundary Layer sampling site in Ucluelet is jointly supported and maintained by Environment Canada, the British Columbia Ministry of the Environment and Metro Vancouver. We acknowledge funding from the Natural Environment Research Council (NE/K004417/1, NE/I020059/1, NE/I013466/1, NE/I028696/1, NE/I019057/1, NE/H009485/1), the European Research Council (FP7, 240449 ICE, BACCHUS 603445), the UK Aerosol Society, National Science Foundation (AGS-1232203), German Research Foundation (WU585/6-1), the Climate Change and Atmospheric Research Program of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (for NETCARE), Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Environment Canada, NOAA’s Climate Program Office (for WACS II), and the DOE Office of Science (BER) Earth System Modeling Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.W.W. organized the ICE-ACCACIA campaign, designed experiments, collected and analysed samples during and after the campaign, managed collaborations and co-wrote this manuscript. L.A.L. designed experiments and analysed samples during the NETCARE campaign and co-wrote this manuscript. P.A.A. collected and analysed STXM/NEXAFS spectra and diatom exudate freezing data and contributed to manuscript writing. M.N.B. collected flow cytometry data for SML samples during ACCACIA. I.M.B. sought funding for ACCACIA and helped design the microlayer sampling procedure. S.M.B., J.V.T., J.B. and K.S.C. performed and analysed the model simulations. C.J. performed heating tests on ICE-ACCACIA samples. W.P.K. assisted with collection of material during the WACS II cruise, provided exudate material for experiments, and participated in STXM/NEXAFS data collection. G.M., J.J.N. and S.R. conducted total organic carbon measurements on Arctic samples. L.A.M., O.W. and E.P. collected the Ucluelet, Line P and open ocean samples, and conducted the NETCARE biogeochemical analysis. C.L.S. helped organize the measurements at the Ucluelet site and facilitated the use of the sampling site. T.F.W. collected and analysed samples during and after the ICE-ACCACIA campaign and assisted with design of experiments. J.D.Y.-H., J.A.H., R.H.M., M.S. and J.P.S.W. collected the Ucluelet samples and helped with the NETCARE experiments. A.K.B. and J.P.D.A. oversaw and organized the NETCARE field campaign and provided financial support for it. D.A.K. and J.Y.A. initiated and designed the STXM/NEXAFS and diatom exudate freezing experiments, contributed to the writing of this manuscript and provided financial support for WACS II cruise participation, exudate freezing experiments, and STXM/NEXAFS analyses. B.J.M. established the collaborations necessary for this paper, helped to write the paper and oversaw the ICE-ACCACIA campaign and sought funding for it.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Figure 1 Sampling locations.

SML and SSW samples were collected during the ACCACIA campaign (July–August 2013) at Arctic sampling stations at the locations marked with solid red circles. Also shown are sampling locations during the WACS II campaign (May–June 2014) in the North Atlantic Ocean. NETCARE samples were collected at locations in the Northeast Pacific (yellow star and green square, CCGS John P. Tully, 14–19 June 2013). The red diamond and blue asterisk correspond to the sampling locations for the NETCARE British Columbia (BC) coastal samples (12–15 August 2013). The inset is a zoom of the BC coast sampling locations.

Extended Data Figure 2 Effects of heating and filtering on the ice nucleation activity of microlayer samples.

a, The effect of filtering through different pore-sized filters on the temperature at which 50% of droplets had frozen (T50) of Arctic and Atlantic SML samples tested using the μl-NIPI. Error bars represent ± the standard deviation calculated from the freezing temperatures in each experiment, which consisted of between 30 and 53 individual events. Shaded grey area is the range of T50 found for fresh unfiltered SSW during the campaign. b, Comparison of the UT-CFDC onset RHice of unfiltered, filtered (0.2 µm) and heated (to 100 °C for 10 min) North Pacific and BC coast SML and SSW samples. The blue lines, and the red and dark blue symbols are as shown in Fig. 2d. The green symbols represent the filtered onsets, whereas the black symbols represent the heated results. Ice-nucleation-onset error bars represent one standard deviation based on three to four replicates. c, Results of heating tests using Arctic and Atlantic SML samples on T50 tested using the μl-NIPI. Error bars represent ± the standard deviation calculated from the freezing temperatures in each experiment, which consisted of between 28 and 46 individual events. Shaded grey area is the range of T50 found for fresh untreated Arctic SSW.

Extended Data Figure 3 Ice surface site densities for the Pacific microlayer samples.

Comparison of the ice surface densities (ns) calculated from UT-CFDC data for the NETCARE SML samples with literature data. The ns values were obtained at −40 °C assuming that the particles were spherical. The SML ns values are indicated by the coloured symbols, whereas the mineral dust ns values are indicated by the grey symbols. The dark grey and light grey symbols are from refs 21 and 22, respectively.

Extended Data Figure 4 Bacterial cell counts for Arctic samples.

a, Bacterial cell counts from flow cytometry performed on Arctic SSW (black squares), fresh Arctic SML (red circles). b, The SML sample cell counts plotted against T50 (temperature at which 50% of droplets frozen) and line of best fit, R2 = 0.29.

Extended Data Figure 5 Correlation of TEP and DOC with the UT-CFDC RHice onsets.

a, b, Ice nucleation RHice onsets for Northeast Pacific (see Extended Data Table 1) samples plotted against measured DOC concentration (a) and TEP enrichment factor (b). Error bars represent the experimental uncertainty in relative humidity with respect to ice in the UT-CFDC.

Extended Data Figure 6 Ice-nucleating activity of diatoms cells and their exudates.

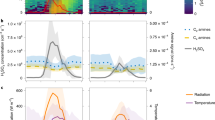

WACIFE frozen fraction curves derived from 60–129-μm-sized droplets (∼0.4 nl volume) as a function of temperature. Green symbols indicate diatom exudates in 0.1-μm-filtered sea water. Blue and red symbols represent 0.1-μm-filtered sea water devoid of exudates with and without the addition of growth media, respectively. All temperatures have been corrected for freezing point depression to pure water conditions from their initial aqueous solution water activity, aw = 0.985 (open circles), 0.97 (open squares), 0.96 (filled diamonds), 0.95 (open diamonds), 0.94 (filled circles), 0.925 (open triangle), 0.90 (asterisks). Shaded areas illustrate ranges of observed heterogeneous ice nucleation of intact and fragmented diatom cells (green) and homogeneous ice nucleation of aqueous NaCl droplets (grey) for similar aw values6,32. Error bars represent the instrumental uncertainty in temperature measurement. Predicted homogeneous freezing temperatures for similar sized water droplets are indicated by the grey bar31,40.

Extended Data Figure 7 TOC and DOC measurements for Arctic samples.

Arctic SML TOC and DOC measurements and Arctic SSW DOC measurements. TOC error bars represent the measured 2% coefficient of variance. DOC sample error was calculated as the coefficient of variation from the mean and standard deviation of three sample replicates. For comparison here we provide the Atlantic TOC measurements; Atlantic SML1 = 5.954 ± 0.185 mg l−1, Atlantic SML2 = 4.643 ± 0.135 mg l−1.

Extended Data Figure 8 μl-NIPI freezing curves for Arctic and Atlantic samples uncorrected for freezing depression caused by salts.

Fraction frozen curves for 1 µl droplet freezing experiments using Arctic and Atlantic ocean samples, uncorrected for freezing point depression. SML, SSW and boat flushing water (grey points; symbols correspond to those for SML sampled at the same locations) to check for the absence of contaminant INPs before sampling.

Extended Data Figure 9 Summary of ice nucleation experimental setups.

a, Pipetting 1 µl droplets onto a hydrophobic glass slide. b, Schematic of the µl-NIPI cold stage used for immersion mode droplet freezing experiments. c, Schematic of the experimental setup for cirrus cloud relevant experiments. CPC, condensation particle counter; DMA, differential mobility analyser; OPC, optical particle counter. d, Schematic of the water-activity-controlled immersion freezing experiment (WACIFE) for freezing of micrometre-sized droplets containing diatom exudates as a function of water activity, aw, and relative humidity, RH. Images are not to scale. The procedure for preparing and freezing droplets of filtered and autoclaved natural sea water with and without added f/2 nutrients droplets is similar except 0.1 μm filtration is not required.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, T., Ladino, L., Alpert, P. et al. A marine biogenic source of atmospheric ice-nucleating particles. Nature 525, 234–238 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14986

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14986

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced singular jet formation in oil-coated bubble bursting

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Ice nucleation catalyzed by the photosynthesis enzyme RuBisCO and other abundant biomolecules

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Regionally sourced bioaerosols drive high-temperature ice nucleating particles in the Arctic

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Aerosolization flux, bio-products, and dispersal capacities in the freshwater microalga Limnomonas gaiensis (Chlorophyceae)

Communications Biology (2023)

-

A critical review on bioaerosols—dispersal of crop pathogenic microorganisms and their impact on crop yield

Brazilian Journal of Microbiology (2023)

Russ Schnell

The paper on marine biogenic ice-nucleating particles is broad and interesting. But, the comment in the introduction beginning on line 10: "However, it has never been directly shown that there is a source of atmospheric INPs associated with organic material found in marine waters or sea-spray aerosol." is not true. Also, much of the data presented as new discoveries have been published more than a quarter century ago, albeit in cruder form reflecting the equipment and knowledge of the time. Only one of the prior papers (#6) discussed below was referenced even though one of the main authors had discussed the contents of the prior papers with me well before the submission of the subject paper.

Here are a few of the omissions that jump to the forefront. My comments follow quotes or references to statements in the subject paper:

A.?organic material in the sea surface microlayer contains active ice nuclei?. This same material was presented in references 1, 2, 3, 4, 10 and 11 listed at the end of this comment. B. ?the material is probably biogenic and 0.2 micrometers in size?. References 1,2,3,4, 5 and 6 show the same results. Reference 5 shows an ice nucleating bacteria shedding organic ice nuclei of the same size. Possibly marine bacteria are different, but the source, size and comparison with prior biogenic ice nuclei research could have been mentioned and compared.

C.?[we} propose that organic material associated with plankton is a likely candidate for ice-nucleating particles?. This was proven in references1, 2, 3, 4, 6 10 and suggested in 10 and 11.

D. ?marine organic materials ?may be sources of ice-nucleating particles. " References 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 have shown this to be the case.

E. In the subject paper, Extended Data, Figure 1. Samples of seawater ice nuclei were collected decades prior in similar locations off British Columbia and the U.S. east coast and published with the same results (References 1, 2 and 3). What is new is the subject paper is the Arctic samples and the modeling.

F. In the subject paper, Figure 2, panels a and b, show that in the most active marine ice nuclei samples there were 10e8 ice nuclei active at -8C per gram of marine plankton material. In Figure 1, (Reference 3) the number of active ice nuclei per gram of marine plankton material was reported earlier to be 10e8 active at -8C.

For less active marine ice nuclei samples shown in the subject paper (Extended Graph, Figure 9), the ranges of marine ice nucleus activity cover the range of the samples presented in Figure 4 (Reference 1). Plankton collected in seawater and in coincident fog water shown in Figures 1 and 2 (Reference 2) have similar ice nucleus concentrations a presented in the subject paper.

G. In the subject paper mention is made of the loss of ice nucleating activity due to heat. In Reference 1, Figure 4, the loss of activity due to heating is shown to occur at even relatively warm temperatures of 30oC. In fact it is difficult to retain the marine ice nuclei activity once the samples are taken out of cold oceans and warmed up.

H. In the subject paper, Figure 4, the authors used atmospheric ice nucleus data (Reference 9) plotted on a map and attributed the ice nuclei to marine organic matter. This same data was plotted on a different map projection (Figure 5, Reference 1) and the ice nuclei suggested to be associated with highly productive plankton zones around Antarctica. Using models, the authors of the subject paper arrive at the same conclusion.

I. There are statements in the paper the marine ice nuclei they observed are organic and around 0.2microns in diameter. There is a large body of literature (~50 papers) showing that organic ice nuclei are produced by bacteria (terrestrial and marine) and are sub-micron (~0.2 micron diameter) protein molecules exuded by the bacteria. This information could have been mentioned in the subject paper. A few earlier references on organic ice nuclei and size are in 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 10,11,12,13 and 14.

J. The ice nucleus site densities presented in the subject paper were determined decades ago (references 7, 8 and 12 and many others).

Prior publications mention in the above discourse.

1. Schnell, R.C. and G. Vali, Biogenic ice nuclei, Part I: Terrestrial and marine sources. J. Atmos. Sci., 33, 1554-1564, 1976.

2. Schnell, R.C., Ice nuclei in seawater, fog water and marine air off the coast of Nova Scotia: Summer, 1975, J. Atmos. Sci., 34, 1299-1305, 1977.

3. Schnell, R.C. and G. Vali, Freezing nuclei in marine waters. Tellus, 27, 321, 1975.

4. Schnell, R.C., Ice nuclei associated with cultured and naturally occurring marine phytoplankton. Geophys. Res. Lett., 2, 500-502, 1975.

5. Phelps P, Giddings TH, Prochoda M, Fall R. Release of cell-free ice nuclei by Erwinia herbicola. Journal of Bacteriology, 167(2):496-502, 1986.

6. Fall R and Schnell RC. Association of an ice-nucleation pseudomonad with cultures of the marine dinoflagellate, Heterocapsa niei. J. Mar Res 43: 257-265,1985.

7. L. R. Maki and K. J. Willoughby, 1978: Bacteria as Biogenic Sources of Freezing Nuclei. J. Appl. Meteor., 17, 1049?1053.

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1...

8. Nemecek-Marshall, M., R LaDuca, and R Fall High-level expression of ice nuclei in a Pseudomonas syringae strain is induced by nutrient limitation and low temperature. J Bacteriol. 1993 Jul; 175(13): 4062?4070. PMCID: PMC204835

9. Bigg, E. K. Ice nucleus concentrations in remote areas. J. Atmos. Sci. 30, 1153?1157 (1973).

10. Knopf, D.A., P. A. Alpert, B. Wang & J. Y. Aller, Stimulation of ice nucleation by marine diatoms. Nature Geoscience, 4, 88?90 , doi:10.1038/ngeo1037, 2011

11. Junge, K & Swanson, B. D. High-resolution ice nucleation spectra of sea-ice bacteria: Implications for cloud formation and life in frozen environments. Biogeosciences 5, 865?873 (2008).

12. Govindarajan, A.G., and S. E. Lindow, Size of bacterial ice-nucleation sites measured in situ by radiation inactivation analysis, Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA

Vol. 85, pp. 1334-1338, 1988.

13. Lindow, S. E, E. Lahue, A. G. Govindarajan, N. J. Panopoulos, and D. Gies Localization of Ice Nucleation Activity and the iceC Gene Product in Pseudomonas syringae and Escherichia coli, MOLECULAR PLANT-MICROBE INTERACTIONS, Vol. 2, No. 5, 262-272, 1989.

14. Turner, MA, Aarelleno, F., Kozloff, LM: Components of Ice Nucleation Structures of Bacteria. J. Bacterial, 173:6515-6527, 1991.

Ben Murray Replied to Russ Schnell

This response was prepared and submitted in 2017 when we were informed of the existence of Dr Schnell’s comment, but it seems to have been ‘lost’. Hence, I have uploaded it again.

We would like to thank Dr. Russell Schnell for his interest in our paper and for bringing up these points that we would like to clarify. Also, we apologize for the late nature of this response, but the authors only became aware of the comments recently.

We recognize the enormous contributions made in the past by Dr. Schnell and others to not only the ice nucleation field but also to our understanding of the connection between marine and atmospheric processes. We did our best to cite a representative set of earlier work within the limited number of citations the Nature format allows and regret that this did not allow us to cite all previous studies that are of potential relevance.

We would like to summarize the main novelties/points of our study, compared to the previous studies cited in the comment: 1) Our study is the first to quantify ice nucleating particles (INPs) in material sampled from the sea surface microlayer (SML, micrometer to millimeter uppermost ocean layer) as opposed to bulk water or mixed bulk-SML sample. We argue that the SML is most relevant to material that would enter sea spray aerosol. 2) We were able to demonstrate a relationship between the total organic carbon (TOC) and number of INPs, providing empirical support for the hypothesis that the INP concentration in the SML is quantitatively related to the presence of organic matter. 3) This is the first parameterization of the INP concentration from the marine organic content for a large data set which included samples from multiple oceans. 4) We demonstrate that the INP (or entity) concentration is vastly higher in the SML sample than in the bulk sea water. 5) We demonstrated that the ice nucleating ability of certain diatom species are associated with the exudate material rather than only the whole phytoplankton cells. 6) This is the first time that the distribution of marine atmospheric INPs as a component of sea spray aerosol is modeled on the basis of an empirically-derived correlation between INP and TOC across multiple samples. 7) We compare our model predictions with the available measurements showing that remote marine organic INP concentrations are consistent with marine organics associated with sea spray aerosol.

We agree that the quantitative agreement with your earlier work on a sample of bulk phytoplanktonic material collected using saturated plankton nets is remarkable (comment f). However, while the data published in 1975 shows there are INPs associated with marine materials, we could not have used this data to predict the ice nucleating particle content of SML samples. We stress that our strategy was to sample the surface active material in the microlayer which we ague is relevant for organic material in sea spray aerosol.

We show in our paper that bulk seawater samples have significantly lower concentrations of INPs than associated SML samples from the same time and location. In contrast to some earlier work (e.g. [Knopf et al., 2011]) we argue that it is not the cells themselves that are important for ice nucleation in the atmosphere, but the organic material associated with those cells. This is a key distinction since the majority of phytoplankton cells are large, their atmospheric residence time is consequentially very low and therefore, their likelihood of reaching cloud altitudes in sufficient numbers is small. In contrast, phytoplankton exudates can be internally mixed with sea salt particles, and we demonstrated with the model that they can be a significant source at the altitudes where mixed-phase clouds form.

Regarding the loss of ice nucleating activity due to heat and organic materials associated with some biological entities acting as INPs, we did not claim this was new for biogenic nucleating material in general. But, it is novel for SML samples.

Regarding the specific comments on heat tests in comment ‘G’, we did not notice such a great sensitivity to heat in our study. As can be seen in the extended data figure 2, the biggest reduction of activity was generally above 80oC, but actually there is a reduction in some samples at much lower temperatures. We cannot see any reference to heat tests in Schnell’s reference 1. There is a statement in Schnell and Vali (1975) that “Tests have shown the ODN to be less than 1 um in diameter (membrane filtration), susceptible to heat (destroyed at 95°C)”.

Regarding comment ‘I’, we agree that there is a large body of evidence that organic materials associated with some biological entities can act as INPs. As mentioned above we could not review the literature, but did cite key papers from which the older literature could be back-referenced (e.g. refs 6, 7, 10, 32 in the paper). In addition to several papers specifically on subcellular ice nucleating entities we cited the following papers that discuss the importance of organics associated with marine organisms: e.g. refs 8, 10, 19, 29 in the paper.

Regarding comment ‘J’, we did not claim this was the first time the ice nucleus site densities are reported, but these are the first for microlayer samples.

References

Knopf, D. A., P. A. Alpert, and J. Y. Aller (2011), Heterogeneous ice nucleation from organic and biogenic material typical of the sea surface microlayer, Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society, 242.