Abstract

Nanotubes behave as semi-flexible polymers in that they can bend by a sizeable amount. When integrating a nanotube in a mechanical resonator, the bending is expected to break the symmetry of the restoring potential. Here we report on a new detection method that allows us to demonstrate such symmetry breaking. The method probes the motion of the nanotube resonator at nearly zero-frequency; this motion is the low-frequency counterpart of the second overtone of resonantly excited vibrations. We find that symmetry breaking leads to the spectral broadening of mechanical resonances, and to an apparent quality factor that drops below 100 at room temperature. The low quality factor at room temperature is a striking feature of nanotube resonators whose origin has remained elusive for many years. Our results shed light on the role played by symmetry breaking in the mechanics of nanotube resonators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A carbon nanotube is a unique system that can be seen both as a crystal and as a polymer. Its crystallinity confers excellent mechanical properties to nanotube-based resonators1,2,3,4,5,6, such as high resonant frequencies7,8 and low dissipation at low temperature9,10. As a result, these resonators are well suited for ultra-sensitive detection of mass11,12, charge2,3 and force13. A nanotube has also much in common with a polymer as both can bend by a large amount. In a resonator, the bending can be generated by the mechanical tension that builds in during the fabrication process as well as by the electrostatic force used in most studies. This curvature is expected to have profound consequences on the dynamics of nanotube resonators, as the transverse vibrational modes lack inversion symmetry.

In a bent nanotube, if one thinks of a vibrational mode as an oscillator, its potential is not symmetric with respect to the displacement from the equilibrium position (Fig. 1a). This leads to a nonlinear term in the restoring force that depends quadratically on the displacement, F2=mβ × δ z2(t) with m the effective mass of the resonator, β a constant quantifying the strength of the symmetry breaking effect and δ z(t) the transverse displacement of the resonator for the given mode. The mechanism underlying the effect can be understood as follows. For a resonator that is curved and clamped at both ends, the length is different for +δ z and −δ z and, therefore, the tension induced by the motion is asymmetric with respect to δ z (Fig. 1b).

(a) Symmetry breaking of the restoring potential U(z). The equilibrium position depends on the energy of the resonator mode. (b) Schematic of a curved resonator. The dashed line represents the static profile of the resonator, that is, when it does not vibrate. The plain lines show the profiles for displacements +δ z and −δ z. (c) The resonator studied consists of a carbon nanotube suspended over a trench between source (S) and drain (D) electrodes. A gate electrode (G) is defined at the bottom of the trench. The trench has a width of 1.8 μm and a depth of ~350 nm. (d,e) The vibrational motion is amplitude modulated at a slow angular frequency ωAM. As a result, the equilibrium position is modulated with the same period.

In a potential with broken symmetry, the equilibrium position of the mode depends on its vibrational amplitude zvibra (see Fig. 1a). Indeed, if the resonator vibrates as δ z(t)=zvibra × cos(ω t), the quadratic term in the restoring force becomes

The second term in the bracket leads to the second overtone, that is, motion at 2ω. The first term corresponds to a time-independent force and, therefore, generates a shift of the equilibrium position, δ zeq. In other words, it is possible to move the equilibrium position by varying zvibra. The timescale of this motion is characterized by the ring-down time associated to zvibra. When considering the thermal motion of such a resonator, the power spectrum of the displacement is expected to feature a peak at zero-frequency, its width being roughly the inverse of the ring-down time14,15. To the best of our knowledge, this low-frequency motion of the equilibrium position of oscillators with high quality factor Q has not been observed in nanomechanical resonators or other condensed-matter systems.

Here we report on a new method to measure the motion of the equilibrium position in response to resonant excitation of the vibrations. We use this method to determine the symmetry breaking strength. We further discuss the connections between symmetry breaking and the mechanics of nanotube resonators. Symmetry breaking controls the dependencies of the resonance frequency on the constant voltage applied to the gate electrode and on the amplitude of the driving force. It leads to the dependance of the resonance frequency on the vibrational amplitude; this dependence induces a sizeable spectral broadening of the mechanical resonances at room temperature.

Results

Device

The device consists of a single carbon nanotube that is clamped by two metal electrodes and is suspended over a trench. A gate electrode is defined at the bottom of the trench (Fig. 1c). The fabrication is described elsewhere10. Briefly, we pattern the three electrodes and the trench using standard electron-beam lithography techniques. We grow the nanotube by chemical vapour deposition in the last fabrication step in order to avoid contamination9. All measurements are performed at 65 K to avoid Coulomb blockade2,3. We have studied five nanotube devices in total. We discuss in the following the data for one device. Data for a second device yielding similar results are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 and discussed in Supplementary Note 1.

Detection method

We use a new technique to detect the motion of nanotube resonators. We capacitively drive the vibrations at ωdrive near the resonant angular frequency ω0 by applying a constant voltage  and an oscillating voltage of amplitude

and an oscillating voltage of amplitude  on the gate electrode. Central to the technique is that the oscillating voltage is amplitude modulated (AM). The resulting displacement near ω0 for not too large

on the gate electrode. Central to the technique is that the oscillating voltage is amplitude modulated (AM). The resulting displacement near ω0 for not too large  is proportional to the driving amplitude,

is proportional to the driving amplitude,

where the amplitude modulation has a depth of 100% and its angular frequency ωAM is typically 2π × 1 kHz (Fig. 1d; we checked that the measurements do not depend on ωAM for ωAM up to 2π × 10 kHz); φm is the phase difference between the displacement and the driving force. We apply a constant voltage  to the source electrode and measure from the drain electrode the low-frequency current at ωAM with amplitude ILF using a lock-in amplifier (Fig. 1e; see Methods for details). We show below that this technique allows us to measure the motion of δ zeq associated with the symmetry breaking in nanotube resonators.

to the source electrode and measure from the drain electrode the low-frequency current at ωAM with amplitude ILF using a lock-in amplifier (Fig. 1e; see Methods for details). We show below that this technique allows us to measure the motion of δ zeq associated with the symmetry breaking in nanotube resonators.

We observe that ILF features a peak when ωdrive is swept through a mechanical resonance (Fig. 2a); the mechanical resonance is also verified by directly measuring the vibrational motion using the frequency modulation (FM) mixing technique (Fig. 2b)4. The height  of the peak in ILF goes linearly to zero as

of the peak in ILF goes linearly to zero as  is decreased (Fig. 2c,d; black squares). These data show that the detected peak in ILF is related to the modulation of the nanotube conductance δ G=ILF/

is decreased (Fig. 2c,d; black squares). These data show that the detected peak in ILF is related to the modulation of the nanotube conductance δ G=ILF/ at ωAM. It rules out an artefact related to the capacitive coupling between the gate and the source electrodes. (This coupling could result in a sizeable AM oscillating voltage at the source electrode, and could thus drive the resonator, but ILF would then be independent of

at ωAM. It rules out an artefact related to the capacitive coupling between the gate and the source electrodes. (This coupling could result in a sizeable AM oscillating voltage at the source electrode, and could thus drive the resonator, but ILF would then be independent of  .)

.)

(a) Low-frequency current ILF measured at angular frequency ωAM as a function of angular driving frequency ωdrive. We use an oscillating gate voltage  =0.53 mV, a source voltage

=0.53 mV, a source voltage  =10 mV and a gate voltage

=10 mV and a gate voltage  =−0.45 V. (b) Mechanical vibrations detected with the FM technique4. VFM=1.1 mV and

=−0.45 V. (b) Mechanical vibrations detected with the FM technique4. VFM=1.1 mV and  =−0.45 V. (c) ILF versus ωdrive with

=−0.45 V. (c) ILF versus ωdrive with  =1.1 mV,

=1.1 mV,  =10 mV and

=10 mV and  =−0.4 V. (d) The height

=−0.4 V. (d) The height  of the peak in ILF as a function of

of the peak in ILF as a function of  measured at ωAM (black squares) and 2ωAM (open squares).

measured at ωAM (black squares) and 2ωAM (open squares).  =2.2 mV and

=2.2 mV and  =−0.4 V.

=−0.4 V.

We also observe a current peak when setting the reference (angular) frequency of the lock-in amplifier to 2ωAM. The peaks measured at ωAM and 2ωAM are similar in that they appear at the same driving frequency and their heights depend linearly on  (Fig. 2d). However, the height of the peak measured at 2ωAM is four times smaller. These observations suggest that the measured peaks are related to a nonlinearity that scales as (δ z(t))2 and therefore

(Fig. 2d). However, the height of the peak measured at 2ωAM is four times smaller. These observations suggest that the measured peaks are related to a nonlinearity that scales as (δ z(t))2 and therefore  . (Indeed, if δ z(t)

. (Indeed, if δ z(t) 1−cos(ωAMt), any physical quantity that is proportional to (δ z(t))2 will be modulated at ωAM and 2ωAM with a ratio of four between the amplitudes of the two components.)

1−cos(ωAMt), any physical quantity that is proportional to (δ z(t))2 will be modulated at ωAM and 2ωAM with a ratio of four between the amplitudes of the two components.)

Estimation of vibrational amplitude

We estimate zvibra≃2.1 nm at resonant frequency for the driving force used in Fig. 2c. For this, we use the 2-source mixing technique with a driving voltage of 1.1 mV (Fig. 3a,b). The value of zvibra is inferred by comparing the signals on and away from the resonance16 (see Methods).

(a) X quadrature ( ) and (b) Y quadrature (

) and (b) Y quadrature ( ) of the current measured with the lock-in amplifier.

) of the current measured with the lock-in amplifier.  consists of a current proportional to the in-phase component of the vibrational displacement in addition to a purely electrical background current.

consists of a current proportional to the in-phase component of the vibrational displacement in addition to a purely electrical background current.  is proportional to the quadrature component of the vibrational displacement. The oscillating gate voltage is

is proportional to the quadrature component of the vibrational displacement. The oscillating gate voltage is  =1.1 mV, the oscillating source voltage

=1.1 mV, the oscillating source voltage  =0.3 mV and the constant gate voltage

=0.3 mV and the constant gate voltage  =−0.4 V.

=−0.4 V.

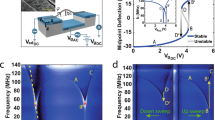

Driving different eigenmodes

The peak in ILF is detected only for a fraction of the mechanical eigenmodes. In the resonator discussed thus far, the peak is observed for the second eigenmode but not for the first one (by comparing ILF in Fig. 4a and the current in Fig. 4b obtained with the FM mixing technique). In all the five studied resonators, we find that about half of the eigenmodes feature a peak in ILF.

(a) Low-frequency current ILF measured at angular frequency ωAM as a function of angular driving frequency ωdrive and constant gate voltage  . The oscillating gate voltage is

. The oscillating gate voltage is  =0.53 mV, and the source voltage

=0.53 mV, and the source voltage  =10 mV. Colour bar: 0 (white) to 280 pA (dark red). The background signal varies with

=10 mV. Colour bar: 0 (white) to 280 pA (dark red). The background signal varies with  ; this variation likely has a purely electrical origin. The number of measurement points is kept as low as possible so that resonances are captured with about three points along the frequency axis. (b) Current as a function of ωdrive and

; this variation likely has a purely electrical origin. The number of measurement points is kept as low as possible so that resonances are captured with about three points along the frequency axis. (b) Current as a function of ωdrive and  measured with the FM technique. VFM=2.2 mV. Colour bar: 0 (white) to 170 pA (dark red). (c) Measured lineshapes of ILF as a function of ωdrive for different

measured with the FM technique. VFM=2.2 mV. Colour bar: 0 (white) to 170 pA (dark red). (c) Measured lineshapes of ILF as a function of ωdrive for different  .

.  =4.2, 3.5, 2.5, 1.6, 1 and 0.6 mV, from top to bottom. (d) Resonance shift extracted from the data in c (black dots) and from FM measurements (open squares).

=4.2, 3.5, 2.5, 1.6, 1 and 0.6 mV, from top to bottom. (d) Resonance shift extracted from the data in c (black dots) and from FM measurements (open squares).

Discussion

We now discuss different possible origins of the peak in ILF. It could be related to the nonlinear capacitive coupling between the nanotube and the gate electrode, which leads to a (δ z(t))2 nonlinearity in the conductance of the nanotube. However, we estimate that the current associated to this effect is  =10 pA, which is 20 times smaller than the measured value in Fig. 2c (Methods). Thus, we reject the (δ z(t))2 nonlinearity induced by the capacitive coupling as the physical origin of the peak in ILF. Neither is the ILF peak attributed to the nonlinearity of the conductance in gate voltage9, as it leads to a current that is three orders of magnitude lower than that measured in Fig. 2c (Methods). Another mechanism for the ILF peak could be the piezoresistance of the nanotube, whose dependence on the displacement is quadratic to a good approximation17. The piezoresistance effect in nanotubes is by far strongest for positive gate voltages (where electrons tunnel from the p-doped regions of the nanotube near the metal electrodes into the n-doped region of the suspended part of the nanotube18,19). However, the observed height of the peak in ILF can be as large for negative as for positive gate voltages (see Fig. 4a). We can thus rule out the piezoresistive effect.

=10 pA, which is 20 times smaller than the measured value in Fig. 2c (Methods). Thus, we reject the (δ z(t))2 nonlinearity induced by the capacitive coupling as the physical origin of the peak in ILF. Neither is the ILF peak attributed to the nonlinearity of the conductance in gate voltage9, as it leads to a current that is three orders of magnitude lower than that measured in Fig. 2c (Methods). Another mechanism for the ILF peak could be the piezoresistance of the nanotube, whose dependence on the displacement is quadratic to a good approximation17. The piezoresistance effect in nanotubes is by far strongest for positive gate voltages (where electrons tunnel from the p-doped regions of the nanotube near the metal electrodes into the n-doped region of the suspended part of the nanotube18,19). However, the observed height of the peak in ILF can be as large for negative as for positive gate voltages (see Fig. 4a). We can thus rule out the piezoresistive effect.

It is compelling to assume that the peak in ILF is due to symmetry breaking of the vibrations. For the AM modulation [1−cos(ωAMt)], ILF depends on the maximal displacement of the equilibrium position δ

[1−cos(ωAMt)], ILF depends on the maximal displacement of the equilibrium position δ as

as

where δ is proportional to

is proportional to  . Here ∂zCg is the derivative of the nanotube-gate capacitance Cg with respect to displacement; it is determined from Coulomb blockade measurements at helium temperature (see Supplementary Fig. S2). From the measured

. Here ∂zCg is the derivative of the nanotube-gate capacitance Cg with respect to displacement; it is determined from Coulomb blockade measurements at helium temperature (see Supplementary Fig. S2). From the measured  in Fig. 2c, we get that δ

in Fig. 2c, we get that δ =0.18 nm and β=4.3 × 1024 m−1 s−2 using the relation β=

=0.18 nm and β=4.3 × 1024 m−1 s−2 using the relation β= (Methods).

(Methods).

This value for the symmetry breaking strength can be compared with the one estimated from the measurement of ω0 as a function of the oscillating driving force. Figure 4c,d Shows that the peak in ILF shifts to lower frequency upon increasing the driving force. Disregarding the cubic restoring force (which in nanotubes leads to the shift in the opposite direction, see ref. 20), we obtain from the shift in ω0 that β=4.1 × 1024 m−1 s−2 (Methods). This value agrees with the one estimated from  , demonstrating that the peak in ILF is due to symmetry breaking of the vibrations.

, demonstrating that the peak in ILF is due to symmetry breaking of the vibrations.

The strength of symmetry breaking can be made large in nanotubes, as it scales as  and the length L can be as short as 100 nm (refs 7, 8). This expression is derived for the fundamental mode of a rod (Supplementary Equation S6 in the Supplementary Information of ref. 20), and zs is the characteristic static displacement induced by the bending. Assuming that zs ranges from 1 to 10 nm, and using L=1.8 μm and the graphite density ρ=2,300 kg m−3 and Young modulus E=1 TP, we obtain β=3−30 × 1024 m−1 s−2, which is consistent with the value obtained from our measurements. The quadratic nonlinear force associated to symmetry breaking is three orders of magnitude larger than the quadratic electrostatic force,

and the length L can be as short as 100 nm (refs 7, 8). This expression is derived for the fundamental mode of a rod (Supplementary Equation S6 in the Supplementary Information of ref. 20), and zs is the characteristic static displacement induced by the bending. Assuming that zs ranges from 1 to 10 nm, and using L=1.8 μm and the graphite density ρ=2,300 kg m−3 and Young modulus E=1 TP, we obtain β=3−30 × 1024 m−1 s−2, which is consistent with the value obtained from our measurements. The quadratic nonlinear force associated to symmetry breaking is three orders of magnitude larger than the quadratic electrostatic force,  . The observed decrease of ω0 with the increasing resonant driving in Fig. 4c,d indicates that the cubic nonlinear (Duffing) force has no substantial effect on the dynamics of the resonator. This points out that the actual static deformation zs is large compared with the vibration amplitude (because the dynamical cubic restoring force scales as F3≃F2·δ z(t)/zs), and thus supporting our above assumption that zs=1−10 nm.

. The observed decrease of ω0 with the increasing resonant driving in Fig. 4c,d indicates that the cubic nonlinear (Duffing) force has no substantial effect on the dynamics of the resonator. This points out that the actual static deformation zs is large compared with the vibration amplitude (because the dynamical cubic restoring force scales as F3≃F2·δ z(t)/zs), and thus supporting our above assumption that zs=1−10 nm.

The observation of a peak in ILF for only about half of the mechanical eigenmodes indicates that β varies from one eigenmode to the next. This is something expected from the interplay between the shapes of the vibrational eigenmodes and the static deformation along the nanotube if the static displacement is primarily in one plane. Our data suggest that the static displacement is essentially perpendicular to the gate electrode. In such a geometry, the lowest-frequency eigenmode detected in Fig. 4b corresponds to the lowest-energy mode vibrating (essentially) parallel to the surface of the gate electrode, as shown in ref. 20. A comparatively small static deformation of the nanotube towards the gate electrode does not break the vibration symmetry of this mode (because the elastic tension inside the nanotube is equal for +δ z and −δ z). As a result, ILF should be weak, in agreement with the measurements. The second eigenmode in Fig. 4b is assigned to the lowest-energy mode vibrating in a direction (essentially) perpendicular to the gate electrode20. In the presence of a static deformation towards the gate electrode, this mode experiences symmetry breaking of vibrations. A peak shows up in ILF, as observed in Fig. 4a.

Having shown that symmetry breaking leads to motion at (nearly) zero-frequency, we demonstrate other connections between symmetry breaking and the mechanics of nanotube resonators. A hallmark of nanotube resonators is that the resonance frequency can be widely tuned with  . Symmetry breaking is expected to control this tunability in ω0 by an amount

. Symmetry breaking is expected to control this tunability in ω0 by an amount

as shown in Supplementary Discussion ( is here offset so that

is here offset so that  =0 when ω0 is minimum). We estimate that m≃4 ag assuming that the length of the nanotube is equal to the trench width (1.8 μm) and using the typical radius (1.5 nm) obtained with our chemical vapour deposition recipe. Using the curvature of Δω0(

=0 when ω0 is minimum). We estimate that m≃4 ag assuming that the length of the nanotube is equal to the trench width (1.8 μm) and using the typical radius (1.5 nm) obtained with our chemical vapour deposition recipe. Using the curvature of Δω0( ) near the minimum of ω0, we get that β=3(±1) × 1024 m−1 s−2, which is close to the value estimated above. This result underscores that symmetry breaking is connected to the response of the resonance frequency to

) near the minimum of ω0, we get that β=3(±1) × 1024 m−1 s−2, which is close to the value estimated above. This result underscores that symmetry breaking is connected to the response of the resonance frequency to  . We emphasize that Equation (4) is only valid for not too large

. We emphasize that Equation (4) is only valid for not too large  , as this is the leading-order term of the expansion of ω0 in

, as this is the leading-order term of the expansion of ω0 in  . Our results indicate that β and the bending of the nanotube both remain essentially constant over the whole range of

. Our results indicate that β and the bending of the nanotube both remain essentially constant over the whole range of  that we studied. This suggests that the bending is a consequence of the mechanical tension built in during the fabrication process. In the future, it will be interesting to measure β as a function of

that we studied. This suggests that the bending is a consequence of the mechanical tension built in during the fabrication process. In the future, it will be interesting to measure β as a function of  for other nanotube resonators.

for other nanotube resonators.

In the presence of thermal vibrations, symmetry breaking leads to spectral broadening21. Because the amplitude of thermal vibrations fluctuates in time, the nonlinearity-induced shift in ω0 (Fig. 4d) also fluctuates and, therefore, broadens the mechanical resonance. The broadening in ω0 reads

when the cubic restoring force is negligible compared with the quadratic one (Supplementary Discussion). Using β=4.3 × 1024 m−1 s−2, we get  =2π × 7.5 × 105 Hz at room temperature. This corresponds to an apparent quality factor of 67, which is comparable to the value of ≃50 measured with the FM technique (Supplementary Fig. S3). We emphasize that this broadening is analogous to dephasing of two-level systems and qubits, which sets the characteristic time T2. The measured broadening is not related to dissipation, so that the energy relaxation time could be much longer than 1/

=2π × 7.5 × 105 Hz at room temperature. This corresponds to an apparent quality factor of 67, which is comparable to the value of ≃50 measured with the FM technique (Supplementary Fig. S3). We emphasize that this broadening is analogous to dephasing of two-level systems and qubits, which sets the characteristic time T2. The measured broadening is not related to dissipation, so that the energy relaxation time could be much longer than 1/ (in fact, it is in this case that Equation (5) gives the spectral broadening). For eigenmodes with a small β, the broadening can be due to the cubic restoring force21. Mechanical resonances might be further broadened by the coupling between eigenmodes21, as shown by recent simulations of nanotube resonators22.

(in fact, it is in this case that Equation (5) gives the spectral broadening). For eigenmodes with a small β, the broadening can be due to the cubic restoring force21. Mechanical resonances might be further broadened by the coupling between eigenmodes21, as shown by recent simulations of nanotube resonators22.

We assumed in our analysis of ILF that the response of the amplitude of the vibrational motion is linear with the driving force. When the response becomes nonlinear at large driving forces due to the restoring force nonlinearity, the ratio of ILF at ωAM and 2ωAM is expected to deviate from four. Calculations show that the width of the peak in ILF remains nearly constant upon varying the driving force, in contrast to the measurements in Fig. 4c. A general theory that incorporates nonlinearities in both the restoring force and damping10,23,24,25,26 as well as thermal vibrations is beyond the scope of this article. We note that our new technique to measure the motion of the equilibrium position allows one to study the response of the resonator over a broad parameter range in driving force.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that symmetry breaking leads to motion at nearly zero-frequency in response to resonant excitation of the vibrations. Our results indicate that symmetry breaking of vibrational modes also leads to such important dynamical properties as the apparent low quality factor of nanotube resonators at 300 K, and the shift of the vibration frequency in response to both (i) the static gate voltage and (ii) the amplitude of the oscillating driving force. A future strategy to improve the apparent Q at 300 K is to tune β with the gate voltage in order to compensate the spectral broadening due to symmetry breaking with that due to the Duffing nonlinearity. Symmetry breaking is important for other vibrational systems of current interest, such as graphene resonators10,27,28,29,30,31 and levitating particles32,33,34. Our new technique may help to reveal this effect in such systems. Symmetry breaking also leads to mode mixing and to parametric resonance in response to additive driving. This holds promise for a number of applications, such as controlled mode mixing35,36,37 and phase noise cancellation38,39,40.

Methods

Electrical characterization of the nanotube device

In Supplementary Fig. S2a, we show the electrical conductance G of the nanotube device as a function of the gate voltage  at 65 K. We find this measurement to be reproducible over a timescale of weeks (a current annealing procedure is performed every day to counter the effects of contamination with residual gas particles).

at 65 K. We find this measurement to be reproducible over a timescale of weeks (a current annealing procedure is performed every day to counter the effects of contamination with residual gas particles).

The capacitance Cg between the gate and the nanotube is determined as follows. In the Coulomb blockade regime, the separation between two conductance peaks is given by δ Vg=eCg, where e is the electron charge. From the measurement in Supplementary Fig. S2b, we get Cg=12 aF, which is in agreement with an estimation based on the device geometry:

Here ∈0 is the vacuum permittivity, L=1.8 μm is the nanotube length and d=350 nm is the equilibrium distance between the nanotube and the gate electrode. As we cannot measure the diameter of the nanotube due to the large surface roughness of the electrodes in the studied device, we use a typical value for the radius (r=1.5 nm). We determine ∂zCg and  Cg by differentiating Equation (6) and get ∂zCg=5.6 pF m−1 and

Cg by differentiating Equation (6) and get ∂zCg=5.6 pF m−1 and  Cg=21 μF m−2.

Cg=21 μF m−2.

From the measurements of the resonance frequency as a function of  in Fig. 4b, we obtain a voltage offset of 0.45 V, which corresponds to the work function difference between the nanotube and the gate electrode. This offset in

in Fig. 4b, we obtain a voltage offset of 0.45 V, which corresponds to the work function difference between the nanotube and the gate electrode. This offset in  is included in all the estimates. However, the values of

is included in all the estimates. However, the values of  that we indicate in the text are always the voltages that are applied to the gate electrode.

that we indicate in the text are always the voltages that are applied to the gate electrode.

Measurements of vibrational motion

We discuss first the frequency modulation (FM) technique4. A driving voltage is applied to the source electrode taking the form VFM × cos[ω t+ωδ/ωL × sin(ωLt)], where ω is the carrier angular frequency, ωδ is the angular frequency deviation (typically 2π × 100 kHz) and ωL is the modulation angular frequency (typically 2π × 671 Hz). It results in a current (IFM) at ωL at the drain electrode. This technique has a low current background and is typically more sensitive than the 2-source technique, so we preferentially use it to detect the eigenmodes of a nanotube resonator. The main drawback of the FM technique is that the measured signal is not proportional to zvibra but to the derivative with respect to the frequency of the in-phase component of the displacement.

In the 2-source technique1, we apply a driving voltage  cosω t to the gate electrode in addition to a DC voltage

cosω t to the gate electrode in addition to a DC voltage  . The motion of the nanotube is detected by applying a second voltage

. The motion of the nanotube is detected by applying a second voltage  to the source electrode. The two oscillating voltages are slightly detuned, and the mixing current Imix is measured at the detuning frequency (typically δ ω/2π=10 kHz). When the displacement is written as

to the source electrode. The two oscillating voltages are slightly detuned, and the mixing current Imix is measured at the detuning frequency (typically δ ω/2π=10 kHz). When the displacement is written as  , the mixing current Imix measured with the 2-source technique has the form16

, the mixing current Imix measured with the 2-source technique has the form16

where G is the conductance of the nanotube, and φE is the phase difference between the voltages applied to source and gate. For a properly tuned phase of the lock-in amplifier, the out-of-phase component of the lock-in amplifier output, Y, corresponds to the quadrature of the resonant displacement (third term in Equation (7)), whereas the in-phase component, X, corresponds to the in-phase component of the resonant displacement (second term in Equation (7)) added to a background (first term in Equation 7) that weakly depends on the frequency near resonance with a given mode (we note that it can have contributions from other modes). When the driving frequency matches the resonant frequency, we get for the Y-component of the mixing current Imix, which we denote as  ,

,

where zvibra is the amplitude of resonant forced vibrations. For the considered small  , zvibra is proportional to the amplitude of

, zvibra is proportional to the amplitude of  .

.

Estimation of vibration amplitude

Equation (7) allows estimating the vibration amplitude of the resonator for resonant driving by comparing the out-of-phase current on resonance,  , with the background far from resonance,

, with the background far from resonance,  1,16. Using Equation (6), we get

1,16. Using Equation (6), we get

If we use the distance to the gate electrode d=350 nm and a nanotube radius r=1.5 nm, the measurement in Fig. 3 yields a value of zvibra=2.1 nm for the modulation amplitude  =1.1 mV.

=1.1 mV.

Detection of the motion of the equilibrium position

In the following, we explain in more detail the technique we develop to detect the motion of the equilibrium position of the nanotube resonator due to symmetry breaking. We drive the resonator with an AM-driving force, which causes an AM vibrational motion (Equation 2). The amplitude change of the vibration is quasi-adiabatic from the point of view of the resonator (we checked that the result is independent of the modulation period 2π/ωAM down to 0.1 ms.) In the presence of AM modulation the quadratic nonlinear force F2 δ z(t)2 leads to the oscillation of the nanotube equilibrium position, δ zeq, as illustrated in Fig. 1e.

δ z(t)2 leads to the oscillation of the nanotube equilibrium position, δ zeq, as illustrated in Fig. 1e.

The conductance G of the nanotube is a function of the total charge q of the nanotube. Using Supplementary Equations (S1–S3), the linear dependance of G on the displacement is

The slow oscillation of the conductance is caused by the motion of the equilibrium position due to symmetry breaking. As shown in Fig. 1e, for comparatively weak resonant modulation, where the AM vibrational motion is of the form of δ z(t)=zvibra × cos(ωdrivet) × [1−cos(ωAMt)], the equilibrium position δ zeq

oscillates with period 2π/ωAM. The vibrations are nonsinusoidal,

oscillates with period 2π/ωAM. The vibrations are nonsinusoidal,

The amplitude of the low-frequency current oscillation measured at ωAM is then simply

This current corresponds to the second term in the bracket of Supplementary Equation (S11). By comparing Equation (12) to Equation (8) and recalling that  is defined as the low-frequency current when ωdrive matches the resonant frequency, we get

is defined as the low-frequency current when ωdrive matches the resonant frequency, we get

provided that  and

and  are measured with the same driving force and

are measured with the same driving force and  is taken at the resonant frequency. (The driving force comes from the gate voltage oscillation at frequency ω; however, in the 2-source technique used to measure

is taken at the resonant frequency. (The driving force comes from the gate voltage oscillation at frequency ω; however, in the 2-source technique used to measure  the voltage amplitude is not modulated; we note again that we study the regime where

the voltage amplitude is not modulated; we note again that we study the regime where  is comparatively small.)

is comparatively small.)

Estimation of ILF due to capacitive nonlinearity

In this section, we estimate the current that is expected due to the nonlinearity of the capacitance with respect to displacement,  Cg (see Supplementary Equations (S2, S3 and S11)). From Supplementary Equations (S2 and S3), the current at ωAM that we expect due to the capacitive nonlinearity in the presence of a DC bias voltage (

Cg (see Supplementary Equations (S2, S3 and S11)). From Supplementary Equations (S2 and S3), the current at ωAM that we expect due to the capacitive nonlinearity in the presence of a DC bias voltage ( ) has the form

) has the form

Comparing Equation (14) with Equation (8), we can express this current in terms of the 2-source mixing current measured on resonance in Fig. 3. We get

where the currents are taken at the resonance frequency and for the same amplitude  . This relation is useful, because it depends on a small number of parameters. Using

. This relation is useful, because it depends on a small number of parameters. Using  =37 pA from Fig. 3b,

=37 pA from Fig. 3b,  =10 mV,

=10 mV,  =0.3 mV, ∂zCg=5.6 pF m−1,

=0.3 mV, ∂zCg=5.6 pF m−1,  Cg=21 μF m−2 and zvibra=2.1 nm, we get that

Cg=21 μF m−2 and zvibra=2.1 nm, we get that  =9.7 pA±5 pA, which is far below

=9.7 pA±5 pA, which is far below  =219 pA that we measured in Fig. 2c.

=219 pA that we measured in Fig. 2c.

Estimation of ILF due to conductance nonlinearity

We estimate the current that is expected due to the nonlinearity of the conductance with respect to the gate voltage,  G, which is described by the last term in Supplementary Equation (S1). From Supplementary Equations (S2 and S3), the current at ωAM is

G, which is described by the last term in Supplementary Equation (S1). From Supplementary Equations (S2 and S3), the current at ωAM is

Using  =10 mV,

=10 mV,  =−0.4 V, ∂zCg=5.6 pF m−1, Cg=12 aF, zvibra=2.1 nm and

=−0.4 V, ∂zCg=5.6 pF m−1, Cg=12 aF, zvibra=2.1 nm and  G=54 μS V−2, we get that

G=54 μS V−2, we get that  =0.19 pA. We determine

=0.19 pA. We determine  G by twice differentiating the conductance in Supplementary Fig. S2a with respect to the gate voltage.

G by twice differentiating the conductance in Supplementary Fig. S2a with respect to the gate voltage.

Estimation of the symmetry breaking strength

In the presence of the AM vibrational motion of the form of δ z(t)=zvibra × cos(ωdrivet) × [1−cos(ωAMt)] and in the limit of small δ (such that the leading-order term in the restoring force is m

(such that the leading-order term in the restoring force is m δ z), δ

δ z), δ is related to the parameter β as

is related to the parameter β as

Using Equation (17) together with Equation (13), we arrive at the relation

Here again the currents are taken at the resonance frequency and for the same amplitude  . This relation also depends on a small number of parameters that, in addition, are well characterized. With

. This relation also depends on a small number of parameters that, in addition, are well characterized. With  =37 pA from Fig. 3b,

=37 pA from Fig. 3b,  =10 mV,

=10 mV,  =0.3 mV, ω0=2π × 51 MHz, zvibra=2.1 nm and

=0.3 mV, ω0=2π × 51 MHz, zvibra=2.1 nm and  =219 pA measured in Fig. 2c, we get δ

=219 pA measured in Fig. 2c, we get δ =0.18 nm and β=4.3 × 1024 m−1 s−2.

=0.18 nm and β=4.3 × 1024 m−1 s−2.

An alternative estimation of β is possible using the fact that the symmetry breaking force leads to a shift of the resonance frequency with driving force. We have measured the shift of the resonance frequency as a function of the vibrational amplitude with the FM technique as well as with our new detection technique. The values measured with the two methods agree well and are plotted in Fig. 4d. We use the relation41

where Δω0 is the shift of the resonance frequency and

(γ is the coefficient of the Duffing nonlinearity, see Supplementary Equation (S8)). We estimate γeff=−1.8 × 1032 m−2 s−2 from Equation (19) by inserting zvibra=2.1 nm, ω0=2π × 51 MHz and Δω0≃−2π × 150 kHz from Fig. 4d at the driving voltage  =1.1 mV. We then get β=4.1 × 1024 m−1 s−2 from Equation (20) by assuming that γ is negligible. A nonzero value of γ>0 would slightly increase the estimate for β. See Supplementary Discussion for yet another method to estimate β.

=1.1 mV. We then get β=4.1 × 1024 m−1 s−2 from Equation (20) by assuming that γ is negligible. A nonzero value of γ>0 would slightly increase the estimate for β. See Supplementary Discussion for yet another method to estimate β.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Eichler, A. et al. Symmetry breaking in a mechanical resonator made from a carbon nanotube. Nat. Commun. 4:2843 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3843 (2013).

References

Sazonova, V. et al. Tunable carbon nanotube electromechanical oscillator. Nature 431, 284–287 (2004).

Lassagne, B., Tarakanov, Y., Kinaret, J., Garcia-Sanchez, D. & Bachtold, A. Coupling mechanics to charge transport in carbon nanotube mechanical resonators. Science 325, 1107–1110 (2009).

Steele, G. A. et al. Strong coupling between single-electron tunneling and nanomechanical motion. Science 325, 1103–1107 (2009).

Gouttenoire, V. et al. Digital and FM demodulation of a doubly clamped single-walled carbon-nanotube oscillator: towards a nanotube cell phone. Small 6, 1060–1065 (2010).

Ganzhorn, M. & Wernsdorfer, W. Dynamics and dissipation induced by single-electron tunneling in carbon nanotube nanoelectromechanical systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 175502 (2012).

Benyamini, A., Hamo, A., Kusminskiy, S. V., von Oppen, F. & Ilani, S. Real-space tailoring of the electron-phonon coupling in ultra-clean nanotube mechanical resonators. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1304.2779 (2013).

Chaste, J., Sledzinska, M., Zdrojek, M., Moser, J. & Bachtold, A. High-frequency nanotube mechanical resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 213502 (2011).

Laird, E. A., Pei, F., Tang, W., Steele, G. A. & Kouwenhoven, L. P. A high quality factor carbon nanotube mechanical resonator at 39 GHz. Nano Lett. 12, 193–197 (2012).

Hüttel, A. K. et al. Carbon nanotubes as ultrahigh quality factor mechanical resonators. Nano Lett. 9, 2547–2552 (2009).

Eichler, A. et al. Nonlinear damping in mechanical resonators made from carbon nanotubes and graphene. Nat. Nanotech. 6, 339–342 (2011).

Chiu, H.-Y., Hung, P., Postma, H. W. Ch. & Bockrath, M. Atomic-scale mass sensing using carbon nanotube resonators. Nano Lett. 8, 4342–4346 (2008).

Chaste, J. et al. A nanomechanical mass sensor with yoctogram resolution. Nat. Nanotech. 7, 301–304 (2012).

Moser, J. et al. Ultrasensitive force detection with a nanotube mechanical resonator. Nat. Nanotech. 8, 493–496 (2013).

Krivoglaz, M. A. & Pinkevich, I. P. Concerning one mechanism for absorption of low frequency electromagnetic oscillations by localized states in crystals. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 51, 1151–1161 (1966) [Sov. Phys.-JETP 24, 772-779 (1967)]).

Dykman, M. I., Mannella, R., McClintock, P. V. E., Soskin, S. M. & Stocks, N. G. Zero-frequency spectral peaks of underdamped nonlinear oscillators with asymmetric potentials. Phys. Rev. A 43, 1701–1708 (1991).

Eichler, A., Chaste, J., Moser, J. & Bachtold, A. Parametric amplification and self-oscillation in a nanotube mechanical resonator. Nano Lett. 11, 2699 (2011).

Sansa, M., Fernandez-Regulez, M., San Paulo, A. & Perez-Murano, F. Electrical transduction in nanomechanical resonators based on doubly clamped bottom-up silicon nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 243115 (2012).

Minot, E. D. et al. Tuning carbon nanotube band gaps with strain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 156401 (2003).

Stampfer, C. et al. Nano-electromechanical displacement sensing based on single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 6, 1449–1453 (2006).

Eichler, A., del Álamo Ruiz, M., Plaza, J. A. & Bachtold, A. Strong coupling between mechanical modes in a nanotube resonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 025503 (2012).

Dykman, M. I. & Krivoglaz, M. A. Classical theory of nonlinear oscillators interacting with a medium. Phys. Stat. Sol. (B) 48, 497–512 (1971).

Barnard, A. W., Sazonova, V., van der Zande, A. M. & McEuen, P. L. Fluctuation broadening in carbon nanotube resonators. PNAS 109, 19093 (2012).

Dykman, M. I. & Krivoglaz, M. A. Spectral distribution of nonlinear oscillators with nonlinear friction due to a medium. Phys. Stat. Sol. (B) 68, 111–123 (1975).

Croy, A., Midtvedt, D., Isacsson, A. & Kinaret, J. M. Nonlinear damping in graphene resonators. Phys. Rev. B 86, 235435 (2012).

Zaitsev, S., Shtempluck, O., Buks, E. & Gottlieb, O. Nonlinear damping in a micromechanical oscillator. Nonlinear Dynamics 67, 859–883 (2012).

Lifshitz, R. & Cross, M. C. Reviews of Nonlinear Dynamics and Complexity Vol. 1, (Wiley-VCH (2008)) www.tau.ac.il/ ronlif/pubs/RNDC1-1-2008-preprint.pdf.

Bunch, J. S. et al. Electromechanical resonators from graphene sheets. Science 315, 490–493 (2007).

Chen, C. et al. Performance of monolayer graphene nanomechanical resonators with electrical readout. Nat. Nanotech. 4, 861–867 (2009).

Singh, V. et al. Probing thermal expansion of graphene and modal dispersion at low-temperature using graphene nanoelectromechanical systems resonators. Nanotechnology 21, 165204 (2010).

Song, X. et al. Stamp transferred suspended graphene mechanical resonators for radio frequency electrical readout. Nano Lett. 12, 198–202 (2012).

Reserbat-Plantey, A., Marty, L., Arcizet, O., Bendiab, N. & Bouchiat, V. A local optical probe for measuring motion and stress in a nanoelectromechanical system. Nat. Nanotech. 7, 151–155 (2012).

Chang, D. E. et al. Cavity opto-mechanics using an optically levitated nanosphere. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1005–1010 (2009).

Li, T., Kheifets, S. & Raizen, M. G. Millikelvin cooling of an optically trapped microsphere in vacuum. Nat. Phys 7, 527–530 (2011).

Gieseler, J., Deutsch, B., Quidant, R. & Novotny, L. Subkelvin parametric feedback cooling of a laser-trapped nanoparticle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 103603 (2012).

Yamaguchi, H., Okamoto, H. & Mahboob, I. Coherent control of micro/nanomechanical oscillation using parametric mode mixing. Appl. Phys. Exp. 5, 014001 (2012).

Antonio, D., Zanette, D. H. & López, D. Frequency stabilization in nonlinear micromechanical oscillators. Nat. Commun. 3, 806 (2012).

Faust, T. et al. Nonadiabatic dynamics of two strongly coupled nanomechanical resonator modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 037205 (2012).

Dykman, M. I., Mannella, R., McClintock, P. V. E., Soskin, S. M. & Stocks, N. G. Noise-induced spectral narrowing in nonlinear oscillators. Europhys. Lett. 13, 691 (1990).

Kenig, E. et al. Passive phase noise cancellation scheme. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 264102 (2012).

Villanueva, L. G. et al. A nanoscale parametric feedback oscillator. Nano Lett. 11, 5054–5059 (2011).

Landau, L. D. & Lifshitz, E. M. Mechanics Elsevier (2004).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the European Union through the RODIN-FP7 project, the ERC-carbonNEMS project, and a Marie Curie grant (271938), the Spanish state (FIS2009-11284), the Catalan government (AGAUR, SGR) and the US Army Research Office.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.E. fabricated the devices and carried out the measurements. J.M. participated in the measurements. M.I.D. provided support with the theory and wrote the theoretical part of Supplementary Information. All the authors contributed to writing the manuscript. M.I.D. and A.B. conceived the experiment. A.B. supervised the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S3, Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary References (PDF 1670 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eichler, A., Moser, J., Dykman, M. et al. Symmetry breaking in a mechanical resonator made from a carbon nanotube. Nat Commun 4, 2843 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3843

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3843

This article is cited by

-

Pseudo-break imaging of carbon nanotubes for determining elastic bending energies

Nano Research (2023)

-

Mode coupling bi-stability and spectral broadening in buckled carbon nanotube mechanical resonators

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Visualizing nonlinear resonance in nanomechanical systems via single-electron tunneling

Nano Research (2021)

-

Dynamically-enhanced strain in atomically thin resonators

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Real-time vibrations of a carbon nanotube

Nature (2019)