Abstract

In vivo imaging of small animals offers several possibilities for studying normal and disease biology, but visualizing organs with single-cell resolution is challenging. We describe rotational side-view confocal endomicroscopy, which enables cellular imaging of gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts in mice and may be extensible to imaging organ parenchyma such as cerebral cortex. We monitored cell infiltration, vascular changes and tumor progression during inflammation and tumorigenesis in colon over several months.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The gastrointestinal tract and respiratory airways are major sites of immunological challenge. The interplay among microorganisms, the epithelial barrier, immunity and genetics is critical to control organism homeostasis. Impairment of one or some of these factors can lead to homeostatic imbalance, causing disease such as inflammatory bowel diseases1, diet problems, infectious lung diseases2 and cancer. To investigate the complex mucosal immune system and diseases related to it, small animal models, particularly mice, have been widely used. Animal studies have primarily relied on histological examinations of excised tissues ex vivo. Although well established, this approach provides only static information at a specific time point and therefore is inadequate for investigating dynamic longitudinal events involved, for example, in host-microbial interactions, immune reactions and tumor development. Real-time intravital fluorescence microscopy could be a powerful technique for visualizing such processes in natural environments3,4. Until now, however, in vivo cellular imaging of the mucosa in small animals has been difficult owing to the lack of a noninvasive endoscopic method with high resolution and easy maneuverability.

Recently, considerable effort has been made to realize high-resolution, minimally invasive endoscopy in mice. Laser-scanning confocal endomicroscopy, based on a resonantly vibrating fiber or a fiber bundle, has shown a potential for cellular examination of the colon5,6. The front-view configuration of the instruments requires direct contact of the probe perpendicular to the intestinal wall. Although such a contact probe would be viable in a human individual5, it has proven very difficult to maneuver in small animals, such as mice, because of their small lumen diameters. Noncontact endoscopes have been developed to provide a fish-eye view similar to conventional clinical colonoscopy7,8. But this approach requires a large depth of field for a given limited aperture size, and therefore, microscopic resolution could not be achieved. Microendoscopy using graded-index (GRIN) lenses has been demonstrated for imaging brain neural circuitry9 and muscle kinetics10 in mice. However, the field of view of such a high-resolution probe is typically only 5% of its cross-sectional area, seriously limiting the size of tissue interrogated at a given insertion site.

Here we describe a new approach based on a side-view microprobe that overcomes the limitations of current endoscopes and enables wide-area cellular-level fluorescence imaging of tissue in live mice. Contact between the view window and luminal wall makes it easy to navigate along the tract by rotation and translation of the probe. This allowed us to obtain a comprehensive map of fluorescently labeled cells and microvasculature in the mucosa in vivo at multiple time points. We demonstrate the new possibilities enabled by this technology in mouse models of colitis and colorectal tumor.

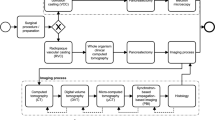

To fabricate a high-resolution side-view endoscopic probe, we modified a 1-mm-diameter triplet GRIN lens microendoscope9,11 and attached an aluminum-coated right-angle prism at the distal end (Fig. 1a). We then sealed the optical unit in a stainless protection sleeve with a transparent epoxy. The assembled rigid endoscope has an outer diameter of 1.25 mm and a length of 50 mm. We integrated the endoscope into a custom-built video-rate scanning-laser confocal microscope11. The laser beam is raster scanned over a fixed x-y plane at the proximal end, so we used a simple image rotation to convert the x-y data to a circumference-lumen frame (Fig. 1b). The endoscope had a field of view of 250 μm × 250 μm and transverse and axial resolution of about 1 and 10 μm, respectively, in the air. The endoscope could be rotated endlessly to change the imaging plane along the circumference. To change the view plane along the lumen, we moved the mouse axially by using a motorized translation stage. The focal depth (z) in the tissue was controlled externally without having to move the endoscope or mouse, simply by translating the coupling 40× objective lens to change the distance to the endoscope (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1).

(a) Schematic of a laser-scanning side-view endoscope. The raster-scanned beam in x and y dimensions is relayed by grade-index lenses in the probe and directed by a 90° prism to a side-view window. ζ and φ represent the axial and circumferential coordinates, respectively, in the imaging plane. θ denotes the rotation angle of the probe, or the angle between x and φ axes. (b) Coordinate transform between the proximal (x-y) and distal (ζ-φ) imaging planes. The trace of the raster-scanned beam is depicted in blue solid lines. (c) In the imaging setup, the laser beam emitted from the endoscope is projected to a stage. Dashed lines depict the outline of the beam diverging after going through the imaging plane. Inset, distal tip of the probe. (d) Three-dimensional rendered fluorescence image of the vasculature in the descending colon of a normal C57B6/L mouse. (e) A fly-through rendered image of d. The wall-to-wall diameter is 1.3 mm. (f–h) Fluorescence images of the microvasculature in the esophagus (f), vasculature of villi in the small intestine (g) and MHC-II–GFP expression in dendritic cells in the trachea (h). Blood vessels were visualized by intravenously injected FITC-dextran conjugates. In f–h, the horizontal axis represents the circumferential angle φ. Scale bars, 200 μm.

To perform wide-area imaging, we used rotational and axial scanning; the probe scans along the luminal length repeatedly at different angles or, alternatively, along a helical path. During scanning, we continuously acquired a movie at 30 frames per second (512 × 512 pixels per frame). We rotated each frame according to the probe angle and applied image registration to display the entire scanned area (Supplementary Fig. 2). We obtained a wide-area vasculature image in the descending colon of an 8-week-old mouse in vivo after intravenous injection of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran conjugates. We rendered a three-dimensional image of the microvasculature, constructed from a total of 60,000 frames acquired in 2,000 s over a 12-mm-long section (Fig. 1d). The dataset can be presented in various ways such as a flythrough view (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Video 1) and a two-dimensional presentation. The high spatiotemporal resolution enabled quantitative analysis of vascular parameters such as flow velocity and vessel diameters (Supplementary Video 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). The small-diameter probe was also well-suited for esophageal imaging via trans-oral endoscopy (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Video 3). We also imaged the extensive network of the vessels and mucosal dendritic cells in the small intestine through a gastric 'feeding' tube (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 4) and in the airway by bronchoscopy (Fig. 1h). The high resolution of the side-view probe allowed us to visualize the interaction of mucosal dendritic cells with fluorescently labeled antigens (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Video 4).

To use the probe for quantitative cellular imaging, we performed wide-area colonoscopy in Foxp3-GFP reporter mice (Online Methods) over the course of acute colitis induced by adding dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) to the drinking water for 5 d. In these mice, the regulatory T (Treg) cell–specific transcription factor FoxP3 is expressed along with GFP. We visualized the FoxP3+ GFP+ Treg cells over a 2 mm (circumference) × 5 mm (lumen) × 50 μm volume of the colonic mucosa repeatedly on the following days relative to the start of DSS treatment: −1 (normal colon), 3 (acute phase of colitis), and 7 and 14 (recovery phase). In the normal state, Treg cells were distributed sparsely (Fig. 2a,b). We observed a substantial increase in the number of Treg cells during the course of DSS-induced colitis (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 6), which supports a recent finding that a breach in the epithelial barrier enhanced the expansion of Treg cells in the colon12.

(a) Map of GFP-expressing Treg cells taken before DSS treatment (day −1). (b) Magnification of the boxed area in a, showing Treg cells (green) and blood vasculature (red). Inset, close-up of the boxed region. (c) A typical image of Treg cells at day 7 in the recovery phase of colitis. Blood vessels in b were visualized by intravenously injected Evans Blue. Scale bars, 200 μm (20 μm in the inset).

Next, we used side-view colonoscopy to investigate spontaneous colorectal tumorigenesis. We used an inducible tumor model13 in which the 'floxed' adenomatosis polyposis coli (Apc) gene is inactivated by administration of adenoviral vector encoding the Cre recombinase (adeno-Cre) into the colon. This mouse model mimics the somatic mutation observed in most individuals with colorectal cancer and enabled us to control the location and timing of the onset of tumorigenesis. Necropsy taken at 16–18 weeks after introduction of adeno-Cre revealed that all of the floxed Apc mice treated with adeno-Cre (n = 13) developed a few large adenomatous polyps in the descending colon. Control mice that received saline only (n = 4) did not have polyps. We performed in vivo colonoscopy in these mice every 2 weeks from week 9 until week 19 and imaged the blood vessels in a segment of descending colon about 5 to 25 mm from the anus. In the Apc conditional knockout mice, but not in the control mice, we observed regions with abnormal vasculature. A vascular image taken at 11 weeks revealed a small lesion ∼500 μm in diameter, characterized by vessel dilation and increased spacing between vessels (Fig. 3a). In the same mouse imaged at 13 weeks, this anomalous area had grown to a size of ∼1.5 mm; we observed a strong fluorescent signal from fluorescent tracer (FITC-dextran) that had presumably leaked from the vessels and transiently accumulated in the middle of the lesion (Fig. 3b). We confirmed the formation of tumors by examining sections of dissected colon (Supplementary Fig. 7). In another mouse, at week 17, we observed a larger lesion ∼4 mm in diameter with severe vessel dilation, tortuous vasculature and elevated leakage of fluorescent tracer (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Video 5). These features are typical for angiogenic vessels associated with tumor development, which we confirmed by histology analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7).

(a–c) Fluorescence image of colorectal vasculature in a floxed Apc mouse at 11 weeks (a) and 13 weeks (b) after adeno-Cre administration, and of a large lesion at week 17 in another adeno-Cre–treated mouse (c). (d) Fluorescence images of Apc-knockout GFP+ cells (green) and blood vessels (red) at the same site in the descending colon, observed at days 10, 12, 14 and 28. Each image is a projection view of 50-μm z-dimension stack. The images show a GFP+ lesion that appeared to grow (*). Other GFP+ nodules shrunk (arrowhead) or vanished at day 28 (dashed circle). Blood vessels were visualized by intravenously injected FITC-dextran in a–c and by tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA)-dextran in d. Scale bars, 200 μm.

We then engineered the mouse model so that the Apc inactivation was accompanied by constitutive expression of GFP13. Side-view endomicroscopy enabled us to observe the formation of GFP-expressing Apc-knockout cells and to monitor their progression over time. We identified multiple groups of GFP+ cells typically within the first two weeks after adeno-Cre administration (Fig. 3d). From z-dimension stack images (50 μm), we could determine the volume of small nodules over time. By this measure, some of these lesions continued to grow, whereas others apparently shrank or vanished (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 8). These results demonstrate the possibility of using our side-view endoscope to monitor the fate of these cells in vivo from the moment of genetic mutation to the formation of large adenomas.

In addition to genetic predisposition, the stromal microenvironment is important in the initiation and progression of tumors4. Side-view endomicroscopy can be used to visualize a variety of events, such as vascular changes, matrix modulation and circulating cell infiltration, during development and treatment, and thus we expect it to be a powerful research tool in oncology. Also, it may also be used to directly monitor the transport of orally or systemically administered therapeutic agents, including nanoparticles, across the epithelial and endothelial barriers in the intestine and other organs, providing insights into new therapeutics14. Finally, 'needle' endoscopy9 is an effective way to access internal tissues of solid organs. The side-view microprobe offers the possibility of visualizing the entire tissue surface along the insertion hole (Supplementary Fig. 9), which may prove useful in investigating brain diseases and neural signaling15.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Methods website.

Methods

Side-view endomicroscope.

We fabricated the side-view endoscopes in-house using 1-mm-diameter graded-index lenses (NSG America) and aluminum-coated right-angle microprisms (base length = 0.7 mm). The lens unit had a triplet structure with a magnification of 0.84, comprising a proximal coupling lens (ILW, pitch = 0.25), a relay lens (SRL, pitch = 1) and a distal imaging lens (ILW, pitch = 0.16). We attached the microprism to the end surface of the imaging lens. The assembled optical unit was inserted into a stainless sleeve and glued. UV epoxy (Norland 81) was used to create a protective and transparent window at the distal tip (Fig. 1). The finished endoscope was mounted on a custom-built x-y-z translational and rotational stage and coupled into a custom-built confocal imaging system11.

Imaging system.

Our imaging system was built on a video-rate scanning laser confocal microscope platform previously described. The system has two continuous-wave lasers with emission at both 491 nm and 532 nm (Dual-Caylpso; Cobolt) and 635 nm (Radius; Coherent), respectively. For video-rate raster scanning, we used a custom-developed scanner comprised of an aluminum-coated polygonal mirror (MC-5; Lincoln Laser) and a galvanometer (6220H; Cambridge Technology). The scanner was configured to provide a field of view of 250 × 250 μm at the focal plane of a 40× objective lens (LUCPlanFl, numerical aperture (NA) = 0.6; Olympus). The objective lens was mounted on a linear translational stage for fine control of the distance from the GRIN probe. Three photomultiplier tubes (PMT, R9110; Hamamatsu) were used as fluorescence detectors, which were placed after multilayer color filters (Semrock) and confocal pinholes. The PMT outputs were digitized by an 8-bit 3-channel frame grabber (Solios; Matrox) at ten million samples per second each channel. Images were displayed on a computer monitor at a frame rate of 30 Hz (512 × 512 pixels per frame, 3 windows) and stored in a hard disk in real time by using custom-written software and Matrox Imaging Library (MIL9).

Wide-area image acquisition and processing.

We used image registration to produce a wide-area image from the movie acquired by the rotational and pullback operation of a side-view endoscope. The scan speed of the endoscope was controlled to be typically 100–200 μm s−1. With a frame rate of 30 frames per second and a field of view of 250 × 250 μm, this ensured that there is sufficient overlap in position between adjacent frames for image registration. Individual images were rotated according to the angular position of the rotational stage of the endoscope (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Then, we applied an image registration algorithm16 written in Matlab (MathWorks) to merge the individual frames to produce a wide-area image. This process enhanced image contrast by averaging the noise over multiple frames and also effectively removed artifacts resulting from tissue motion such as breathing (for more information, see Supplementary Fig. 2). The three-dimensional presentation of vasculature images (Fig. 1d,e) was made using SketchUp Pro 7 (Google).

DSS-induced mouse model of acute colitis.

We used FoxP3-GFP knock-in mice17 (5 weeks old, female). We added 3.5% (wt/vol) dextran sulfate sodium (DSS; 36,000–50,000 MW; MP Biomedicals) to drinking water for 5 d. The DSS treatment was terminated from day 6 to induce the recovery process from the inflammation.

Conditional Apc knockout model of colorectal tumor.

We used floxed Apc mice13. The administration of adenoviral Cre into the colon epithelia can inactivate the Apc gene, which mimics somatic Apc mutation in human individuals with sporadic colorectal cancer. Apc-GFP mice were homozygous for a floxed exon 14 of the Apc allele and heterozygous for a latent GFP reporter allele13,18. For adeno-Cre delivery, we anesthetized the mouse at the age of 8 weeks by inhalation anesthesia (4% isoflurane, oxygen flow 1.5 l min−1) and made a 3–4-cm midline incision along about one-half the length of the lower abdomen. A 5 × 0.8 mm 10 g pressure vessel clip was placed proximally around the colon about 2 cm from the anus. A 3-cm-long polyethylene tube (0.28 mm inner diameter) attached to a 1-cc syringe was introduced into the colon through anus until the extent of the proximal clip. A second clip was placed 1 cm distal to the first one. We infused 100 μl of adenovirus (Ad5CMVCre; Gene Transfer Vector Core, University of Iowa) and incubated for 30 min. After removing both clips, the wound was closed with 4.0 silk sutures in two layers. Control mice were prepared by the same surgical procedure without adeno-Cre transduction.

In vivo mouse imaging.

Before in vivo imaging, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine-xylazine anesthesia (90 mg and 9 mg, respectively, per kilogram of body weight). Eye ointment was applied to protect the cornea from dehydration during anaesthetization. The mice were placed on a heated plate of a motorized x-y-z translational stage. For vasculature imaging, we injected fluorescent tracer intravenously. Images were typically acquired within 5–40 min after the injection. FITC-dextran conjugates (500 μg in 100 μl, 2,000,000 MW, FD2000S; Sigma Aldrich) was used for experiments shown in Figures 1d–g,3a–c; TAMRA-dextran conjugates (500 μg in 100 μl, 2,000,000 MW; Invitrogen) was used for the experiment shown in Figure 3d; and Evans Blue dye (1 μg in 100 μl; Sigma Aldrich) was used for the experiment shown in Figure 2b. GFP-expressing cells and the FITC vessel tracer were visualized by excitation at 491 nm and detection through a bandpass filter at 502–537 nm (Semrock). TAMRA was imaged by excitation at 532 nm and detection through a bandpass filter at 562–596 nm (Semrock). Evans Blue was excited at 635 nm and detected at 672–712 nm. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with institutional guidelines and approved by the subcommittee on research animal care at the Massachusetts General Hospital.

In vivo esophageal imaging.

The mouse was laid down on the heated plate. A small block of gauze was placed under the neck. The plate was tilted to make a straight access for the endoscope through the mouth into the esophageal tract. We opened the mouth using forceps, gently pulled and pushed down the tongue using a cotton tip, and inserted a side-view endoscope through the mouth. Care was taken not to obstruct the airway. Breathing of the mouse was monitored during imaging.

In vivo percutaneous imaging of the small intestine.

Small-intestine imaging was done via laparotomy. The mouse was laid down on the heated plate. After making a midline incision in the skin, we placed the jejunum over the center of the surgical opening by using cotton tips. Saline was applied to the exposed jejunum regularly during imaging to prevent the tissue from drying out. With an 18-gauge needle, we made a small hole on the jejunum. Through the hole, we injected 0.5 ml of distilled water, which serves as a lubricant, and inserted a side-view endoscope.

In vivo colonoscopy.

Before gastrointestinal imaging, mice were starved for 24 h before imaging to avoid strong autofluorescence signal of mouse excrement and digested food. We dilated the colon by injecting 0.5 ml of distilled water via enema using a rubber-tipped needle. The injected water also served as a lubricant during endomicroscopy, avoiding tissue damage. We applied a small drop of 2% methylcellulose (Methocel; Dow) onto the tip of a side-view endoscope, which also served as a lubricant and helped the endoscope pass through the anus.

In vivo tracheal imaging.

Before imaging, we performed tracheotomy to open a direct airway for breathing through a small incision on the trachea. We then inserted a side-view probe into the trachea through the mouth.

In vivo brain imaging.

We used a Hist1h2bb-GFP transgenic mouse (12-weeks-old, female; Jackson Laboratory) in which all the cell nuclei were green fluorescent. A craniotomy was performed under anesthesia before imaging. After applying a drop of saline, we inserted a GRIN side-view probe deep into the brain. We then performed wide-area imaging by a helical pullback scanning of the probe.

References

Xavier, R.J. & Podolsky, D.K. Nature 448, 427–434 (2007).

Mizgerd, J.P. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 716–727 (2008).

Miller, M.J., Wei, S.H., Parker, I. & Cahalan, M.D. Science 296, 1869–1873 (2002).

Jain, R.K., Munn, L.L. & Fukumura, D. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 266–276 (2002).

Kiesslich, R., Goetz, M., Vieth, M., Galle, P.R. & Neurath, M.F. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 4, 480–490 (2007).

Hsiung, P.L. et al. Nat. Med. 14, 454–458 (2008).

Becker, C., Fantini, M.C. & Neurath, M.F. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2900–2904 (2006).

Funovics, M.A., Alencar, H., Montet, X., Weissleder, R. & Mahmood, U. Gastrointest. Endosc. 64, 589–597 (2006).

Jung, J.C., Mehta, A.D., Aksay, E., Stepnoski, R. & Schnitzer, M.J. J. Neurophysiol. 92, 3121–3133 (2004).

Llewellyn, M.E., Barretto, R.P.J., Delp, S.L. & Schnitzer, M.J. Nature 454, 784–788 (2008).

Kim, P., Puoris'haag, M., Cote, D., Lin, C.P. & Yun, S.H. J. Biomed. Opt. 13, 010515 (2008).

Boirivant, M. et al. Gastroenterology 135, 1612–1623 (2008).

Hung, K.E. et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1565–1570 (2010).

Sanhai, W.R., Sakamoto, J.H., Canady, R. & Ferrari, M. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 242–244 (2008).

Murayama, M. et al. Nature 457, 1137–1195 (2009).

Guizar-Sicairos, M., Thurman, S.T. & Fienup, J.R. Opt. Lett. 33, 156–158 (2008).

Bettelli, E. et al. Nature 441, 235–238 (2006).

Belteki, G. et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 10 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Human Frontier Science Program (cross-disciplinary fellowship 2006), Tosteson Fellowship, National Research Foundation of Korea (R31-2008-000-10071-0) and the US National Institutes of Health (R21AI081010, RC1DK086242, RC2DK088661, U54CA143837, U01CA084301, R01CA85140, P01CA08124, R01CA96915 and R01CA126642).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.K. developed endomicroscopy, performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. E.C. and H.Y. performed the conditional-knockout procedure and helped with angiogenesis imaging. K.E.H. developed the conditional-knockout procedure. A.M. designed the colitis model. R.K., D.F. and R.K.J. designed the tumor model and angiogenesis study. S.H.Y. directed the overall project, developed endomicroscopy and wrote the manuscript with input from other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–9 (PDF 1601 kb)

Supplementary Video 1

Virtual cellular colonoscopy visualizing the microvasculature of normal colonic mucosa. (MOV 4039 kb)

Supplementary Video 2

Real-time endoscopic view of the blood vessels in the normal colon. (MOV 2730 kb)

Supplementary Video 3

Fly-through movie showing the blood vessels of esophageal mucosa. (MOV 2246 kb)

Supplementary Video 4

Time-lapse movie showing the interaction of dendritic cells (green) and Ovalbumin (OVA) allergen (red) at 12 h after OVA challenge. (MOV 735 kb)

Supplementary Video 5

Real-time movie showing the angiogenic blood vessels near the tumor at week 16 after conditional Apc knockout. (MOV 1912 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, P., Chung, E., Yamashita, H. et al. In vivo wide-area cellular imaging by side-view endomicroscopy. Nat Methods 7, 303–305 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1440

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1440

This article is cited by

-

Activation of mechanoluminescent nanotransducers by focused ultrasound enables light delivery to deep-seated tissue in vivo

Nature Protocols (2023)

-

Double-layer polarization-independent achromatic metasurface array for optical fiber bundle coupling in microendoscope

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Clear optically matched panoramic access channel technique (COMPACT) for large-volume deep brain imaging

Nature Methods (2021)

-

Phonon imaging in 3D with a fibre probe

Light: Science & Applications (2021)

-

Handheld endomicroscope using a fiber-optic harmonograph enables real-time and in vivo confocal imaging of living cell morphology and capillary perfusion

Microsystems & Nanoengineering (2020)