Abstract

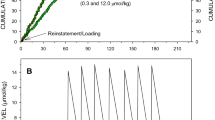

Various self-administration procedures are being developed to model specific aspects of the addiction process. For example, ‘increased cocaine intake over time’ has been modeled by providing long access (LgA) to cocaine during daily self-administration sessions under a fixed-ratio (FR1) reinforcement schedule. In addition, ‘increased time and energy devoted to acquire cocaine’ has been modeled by providing access to cocaine during daily self-administration sessions under a progressive-ratio (PR) schedule. To investigate the distinctiveness of these models, the behavioral economics variables of consumption and price were applied to cocaine self-administration data. To assess changes in consumption and price, cocaine self-administration was tested across a descending series of doses (0.237–0.001 mg per injection) under an FR1 reinforcement schedule to measure drug intake in the high dose range and thresholds in the low range. Cocaine consumption remained relatively stable across doses until a threshold was reached, at which maximal responding was observed. It was found that a history of LgA training produced an increase in cocaine consumption; whereas a history of PR training produced an increase in the maximal price (Pmax) expended for cocaine. Importantly, the concepts of consumption and price were found to be dissociable. That is, LgA training produced an increase in consumption but a decrease in Pmax, whereas PR training produced an increase in Pmax without increasing consumption. These results suggest that distinct aspects of the addiction process can be parsed using self-administration models, thereby facilitating the investigation of specific neurobiological adaptations that occur through the addiction process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC.

Ahmed SH (2005). Imbalance between drug and non-drug reward availability: a major risk factor for addiction. Eur J Pharmacol 526: 9–20.

Ahmed SH, Koob GF (1998). Transition from moderate to excessive drug intake: change in hedonic set point. Science 282: 298–300.

Ahmed SH, Koob GF (1999). Long-lasting increase in the set point for cocaine self-administration after escalation in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 146: 303–312.

Ahmed SH, Koob GF (2005). Transition to drug addiction: a negative reinforcement model based on an allostatic decrease in reward function. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 180: 473–490.

Allen RM, Uban KA, Atwood EM, Albeck DS, Yamamoto DJ (2007). Continuous intracerebroventricular infusion of the competitive NMDA receptor antagonist, LY235959, facilitates escalation of cocaine self-administration and increases break point for cocaine in Sprague–Dawley rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 88: 82–88.

Bickel WK, DeGrandpre RJ, Higgins ST (1993). Behavioral economics: a novel experimental approach to the study of drug dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 33: 173–192.

Bickel WK, DeGrandpre RJ, Higgins ST, Hughes JR (1990). Behavioral economics of drug self-administration. I. Functional equivalence of response requirement and drug dose. Life Sci 47: 1501–1510.

Campbell UC, Rodefer JS, Carroll ME (1999). Effects of dopamine receptor antagonists (D1 and D2) on the demand for smoked cocaine base in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 144: 381–388.

Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME (2002). Effects of bremazocine on self-administration of smoked cocaine base and orally delivered ethanol, phencyclidine, saccharin, and food in rhesus monkeys: a behavioral economic analysis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 301: 993–1002.

Dalley JW, Laane K, Pena Y, Theobald DE, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW (2005). Attentional and motivational deficits in rats withdrawn from intravenous self-administration of cocaine or heroin. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 182: 579–587.

Deroche-Gamonet V, Belin D, Piazza PV (2004). Evidence for addiction-like behavior in the rat. Science 305: 1014–1017.

Emmett-Oglesby MW, Lane JD (1992). Tolerance to the reinforcing effects of cocaine. Behav Pharmacol 3: 193–200.

Emmett-Oglesby MW, Peltier RL, Depoortere RY, Pickering CL, Hooper ML, Gong YH et al (1993). Tolerance to self-administration of cocaine in rats: time course and dose–response determination using a multi-dose method. Drug Alcohol Depend 32: 247–256.

Epstein DH, Preston KL, Stewart J, Shaham Y (2006). Toward a model of drug relapse: an assessment of the validity of the reinstatement procedure. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 189: 1–16.

Ettenberg A (2004). Opponent process properties of self-administered cocaine. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 27: 721–728.

Greenwald MK, Hursh SR (2006). Behavioral economic analysis of opioid consumption in heroin-dependent individuals: effects of unit price and pre-session drug supply. Drug Alcohol Depend 85: 35–48.

Hursh SR (1991). Behavioral economics of drug self-administration and drug abuse policy. J Exp Anal Behav 56: 377–393.

Hursh SR, Silberberg A (2008). Economic demand and essential value. Psychol Rev 115: 186–198.

Lenoir M, Ahmed SH (2008). Supply of a nondrug substitute reduces escalated heroin consumption. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 2272–2282.

Li DH, Depoortere RY, Emmett-Oglesby MW (1994). Tolerance to the reinforcing effects of cocaine in a progressive ratio paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 116: 326–332.

Liu Y, Roberts DC, Morgan D (2005a). Effects of extended-access self-administration and deprivation on breakpoints maintained by cocaine in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 179: 644–651.

Liu Y, Roberts DC, Morgan D (2005b). Sensitization of the reinforcing effects of self-administered cocaine in rats: effects of dose and intravenous injection speed. Eur J Neurosci 22: 195–200.

Lu L, Grimm JW, Hope BT, Shaham Y (2004). Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal: a review of preclinical data. Neuropharmacology 47 (Suppl 1): 214–226.

Lynch WJ, Carroll ME (2001). Regulation of drug intake. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 9: 131–143.

Morgan D, Liu Y, Roberts DC (2006). Rapid and persistent sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 121–128.

Panlilio LV, Katz JL, Pickens RW, Schindler CW (2003). Variability of drug self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 167: 9–19.

Paterson NE, Markou A (2003). Increased motivation for self-administered cocaine after escalated cocaine intake. Neuroreport 14: 2229–2232.

Perry JL, Carroll ME (2008). The role of impulsive behavior in drug abuse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 200: 1–26.

Pettit HO, Justice Jr JB (1989). Dopamine in the nucleus accumbens during cocaine self-administration as studied by in vivo microdialysis. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 34: 899–904.

Pickens R, Thompson T (1968). Cocaine-reinforced behavior in rats: effects of reinforcement magnitude and fixed-ratio size. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 161: 122–129.

Richardson NR, Roberts DC (1996). Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods 66: 1–11.

Roberts DC, Goeders NE (1989). Drug self-administration: experimental methods and determinants. In: Boulton AA, Baker GB, Greenshaw AJ (eds). Neuromethods: Psychopharmacology. Humana Press: Clifton. pp 349–398.

Roberts DC, Morgan D, Liu Y (2007). How to make a rat addicted to cocaine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 31: 1614–1624.

Roberts DC, Zito KA (1987). Interpretation of lesion effects on stimulant self-administration. In: Bozarth MA (ed). Methods of Assessing the Reinforcing Properties of Abused Drugs. Springer: New York. pp 87–103.

Rodefer JS, Carroll ME (1997). A comparison of progressive ratio schedules versus behavioral economic measures: effect of an alternative reinforcer on the reinforcing efficacy of phencyclidine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 132: 95–103.

Schmidt HD, Anderson SM, Famous KR, Kumaresan V, Pierce RC (2005). Anatomy and pharmacology of cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking. Eur J Pharmacol 526: 65–76.

Tsibulsky VL, Norman AB (1999). Satiety threshold: a quantitative model of maintained cocaine self-administration. Brain Res 839: 85–93.

Vanderschuren LJ, Everitt BJ (2004). Drug seeking becomes compulsive after prolonged cocaine self-administration. Science 305: 1017–1019.

Wade-Galuska T, Winger G, Woods JH (2007). A behavioral economic analysis of cocaine and remifentanil self-administration in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 194: 563–572.

Wee S, Mandyam CD, Lekic DM, Koob GF (2008). Alpha 1-noradrenergic system role in increased motivation for cocaine intake in rats with prolonged access. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 18: 303–311.

Wee S, Specio SE, Koob GF (2007). Effects of dose and session duration on cocaine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320: 1134–1143.

Wilson MC, Hitomi M, Schuster CR (1971). Psychomotor stimulant self administration as a function of dosage per injection in the rhesus monkey. Psychopharmacologia 22: 271–281.

Wise RA, Newton P, Leeb K, Burnette B, Pocock D, Justice Jr JB (1995). Fluctuations in nucleus accumbens dopamine concentration during intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 120: 10–20.

Zittel-Lazarini A, Cador M, Ahmed SH (2007). A critical transition in cocaine self-administration: behavioral and neurobiological implications. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 192: 337–346.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Steve Hursh for supplying spreadsheets containing modeling tools that we used to calculate Pmax values. We also thank Leanne Thomas for providing technical assistance and Keri Chiodo for helpful comments in the preparation of this paper. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants F31DA024525 (EBO) and R01DA14030 (DCSR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

DISCLOSURE/CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no related financial interests on considerations to disclose.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oleson, E., Roberts, D. Behavioral Economic Assessment of Price and Cocaine Consumption Following Self-Administration Histories that Produce Escalation of Either Final Ratios or Intake. Neuropsychopharmacol 34, 796–804 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2008.195

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2008.195

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Microbial short-chain fatty acids regulate drug seeking and transcriptional control in a model of cocaine seeking

Neuropsychopharmacology (2024)

-

Intermittent nicotine access is as effective as continuous access in promoting nicotine seeking and taking in rats

Psychopharmacology (2024)

-

Amphetamine maintenance therapy during intermittent cocaine self-administration in rats attenuates psychomotor and dopamine sensitization and reduces addiction-like behavior

Neuropsychopharmacology (2021)

-

Shifts in the neurobiological mechanisms motivating cocaine use with the development of an addiction-like phenotype in male rats

Psychopharmacology (2021)

-

The impact of cocaine and heroin drug history on motivation and cue sensitivity in a rat model of polydrug abuse

Psychopharmacology (2020)