Abstract

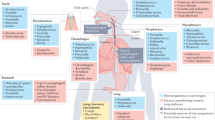

Lung diseases caused by microbial infections affect hundreds of millions of children and adults throughout the world. In Western populations, the treatment of lung infections is a primary driver of antibiotic resistance. Traditional therapeutic strategies have been based on the premise that the healthy lung is sterile and that infections grow in a pristine environment. As a consequence, rapid advances in our understanding of the composition of the microbiota of the skin and bowel have not yet been matched by studies of the respiratory tree. The recognition that the lungs are as populated with microorganisms as other mucosal surfaces provides the opportunity to reconsider the mechanisms and management of lung infections. Molecular analyses of the lung microbiota are revealing profound adverse responses to widespread antibiotic use, urbanization and globalization. This Opinion article proposes how technologies and concepts flowing from the Human Microbiome Project can transform the diagnosis and treatment of common lung diseases.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adams, W. C. California Air Resources Board contract no. A033-205: Measurement of breathing rate and volume in routinely performed daily activities. California Air Resources Board https://www.arb.ca.gov/research/apr/past/a033-205.pdf (1993).

Weibel, E. R. & Gomez, D. M. Architecture of the human lung. Use of quantitative methods establishes fundamental relations between size and number of lung structures. Science 137, 577–585 (1962).

Hasleton, P. S. The internal surface area of the adult human lung. J. Anat. 112, 391–400 (1972).

Bowers, R. M. et al. Sources of bacteria in outdoor air across cities in the midwestern United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6350–6356 (2011).

Helander, H. F. & Fandriks, L. Surface area of the digestive tract — revisited. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 49, 681–689 (2014).

Guest, J. F. & Morris, A. Community-acquired pneumonia: the annual cost to the National Health Service in the UK. Eur. Respir. J. 10, 1530–1534 (1997).

Adriaenssens, N. et al. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): outpatient antibiotic use in Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 (Suppl 6.), vi3–vi12 (2011).

Murphy, T. F. Vaccines for nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: the future is now. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 22, 459–466 (2015).

Dickson, R. P., Erb-Downward, J. R. & Huffnagle, G. B. The role of the bacterial microbiome in lung disease. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 7, 245–257 (2013).

Hilty, M. et al. Disordered microbial communities in asthmatic airways. PLoS ONE 5, e8578 (2010).

Charlson, E. S. et al. Topographical continuity of bacterial populations in the healthy human respiratory tract. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184, 957–963 (2011).

Brook, I. Bacterial interference. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 25, 155–172 (1999).

Reid, G., Howard, J. & Gan, B. S. Can bacterial interference prevent infection? Trends Microbiol. 9, 424–428 (2001).

Falagas, M. E., Rafailidis, P. I. & Makris, G. C. Bacterial interference for the prevention and treatment of infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 31, 518–522 (2008).

Pamer, E. G. Resurrecting the intestinal microbiota to combat antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Science 352, 535–538 (2016).

Ferkol, T. & Schraufnagel, D. The global burden of respiratory disease. Ann. Am. Thorac Soc. 11, 404–406 (2014).

Walker, C. L. et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet 381, 1405–1416 (2013).

Park, D. R. The microbiology of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir. Care 50, 742–765 (2005).

Goss, C. H. & Burns, J. L. Exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. 1: Epidemiology and pathogenesis. Thorax 62, 360–367 (2007).

Donaldson, G. C., Seemungal, T. A., Bhowmik, A. & Wedzicha, J. A. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 57, 847–852 (2002).

Beasley, R. & The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet 351, 1225–1232 (1998).

Cookson, W. The immunogenetics of asthma and eczema: a new focus on the epithelium. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 978–988 (2004).

Johnston, S. et al. Community study of role of viral infections in exacerbations of asthma in 9–11 year old children. BMJ 310, 1225–1229 (1995).

Bisgaard, H. et al. Childhood asthma after bacterial colonization of the airway in neonates. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1487–1495 (2007).

Green, B. J. et al. Potentially pathogenic airway bacteria and neutrophilic inflammation in treatment resistant severe asthma. PLoS ONE 9, e100645 (2014).

Huang, Y. J. et al. Airway microbiota and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with suboptimally controlled asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127, 372–381.e3 (2011).

Goleva, E. et al. The effects of airway microbiome on corticosteroid responsiveness in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 188, 1193–1201 (2013).

Huang, Y. J. & Boushey, H. A. The microbiome in asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135, 25–30 (2015).

Man, W. H., de Steenhuijsen Piters, W. A. & Bogaert, D. The microbiota of the respiratory tract: gatekeeper to respiratory health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 259–270 (2017).

Cardenas, P. A. et al. Upper airways microbiota in antibiotic-naive wheezing and healthy infants from the tropics of rural Ecuador. PLoS ONE 7, e46803 (2012).

Stearns, J. C. et al. Culture and molecular-based profiles show shifts in bacterial communities of the upper respiratory tract that occur with age. ISME J. 9, 1246–1259 (2015).

Molyneaux, P. L. et al. The role of bacteria in the pathogenesis and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190, 906–913 (2014).

Twigg, H. L. et al. Use of bronchoalveolar lavage to assess the respiratory microbiome: signal in the noise. Lancet Respir. Med. 1, 354–356 (2013).

Dickson, R. P. et al. Spatial variation in the healthy human lung microbiome and the adapted island model of lung biogeography. Ann. Am. Thorac Soc. 12, 821–830 (2015).

Salter, S. J. et al. Reagent and laboratory contamination can critically impact sequence-based microbiome analyses. BMC Biol. 12, 87 (2014).

Wilson, L. G. Commentary: Medicine, population, and tuberculosis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 34, 521–524 (2005).

Kennedy, W. A. et al. Incidence of bacterial meningitis in Asia using enhanced CSF testing: polymerase chain reaction, latex agglutination and culture. Epidemiol. Infect. 135, 1217–1226 (2007).

Sethi, S. & Murphy, T. F. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2355–2365 (2008).

Keller, L. E., Robinson, D. A. & McDaniel, L. S. Nonencapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae: emergence and pathogenesis. mBio 7, e01792 (2016).

Siegel, S. J. & Weiser, J. N. Mechanisms of bacterial colonization of the respiratory tract. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 69, 425–444 (2015).

American Thoracic Society & Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171, 388–416 (2005).

Holcombe, L. J., O'Gara, F. & Morrissey, J. P. Implications of interspecies signaling for virulence of bacterial and fungal pathogens. Future Microbiol. 6, 799–817 (2011).

Lessler, J. et al. Incubation periods of acute respiratory viral infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9, 291–300 (2009).

Kuhnert, P. & Christensen, H. Pasteurellaceae: Biology, Genomics and Molecular Aspects (Caister Academic Press, 2008).

Morens, D. M., Taubenberger, J. K. & Fauci, A. S. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J. Infect. Dis. 198, 962–970 (2008).

Bosch, A. A., Biesbroek, G., Trzcinski, K., Sanders, E. A. & Bogaert, D. Viral and bacterial interactions in the upper respiratory tract. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003057 (2013).

Scott, J. A. et al. Aetiology, outcome, and risk factors for mortality among adults with acute pneumonia in Kenya. Lancet 355, 1225–1230 (2000).

McCullers, J. A. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19, 571–582 (2006).

Wilkinson, T. M. et al. Effect of interactions between lower airway bacterial and rhinoviral infection in exacerbations of COPD. Chest 129, 317–324 (2006).

Wheat, L. J., Goldman, M. & Sarosi, G. State-of-the-art review of pulmonary fungal infections. Semin. Respir. Infect. 17, 158–181 (2002).

Pihet, M. et al. Occurrence and relevance of filamentous fungi in respiratory secretions of patients with cystic fibrosis — a review. Med. Mycol. 47, 387–397 (2009).

Kastman, E. K. et al. Biotic interactions shape the ecological distributions of Staphylococcus species. mBio 7, e01157-16 (2016).

Enoch, D. A., Ludlam, H. A. & Brown, N. M. Invasive fungal infections: a review of epidemiology and management options. J. Med. Microbiol. 55, 809–818 (2006).

Hesse, W. Walther and Angelina Hesse – early contributors to bacteriology. ASM News 58, 425–428 (1992).

Croxatto, A., Prod'hom, G. & Greub, G. Applications of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in clinical diagnostic microbiology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 380–407 (2012).

Waters, B. & Muscedere, J. A. 2015 update on ventilator-associated pneumonia: new insights on its prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 17, 496 (2015).

Joos, L. et al. Pulmonary infections diagnosed by BAL: a 12-year experience in 1066 immunocompromised patients. Respir. Med. 101, 93–97 (2007).

Boyton, R. J. Infectious lung complications in patients with HIV/AIDS. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 11, 203–207 (2005).

Bush, K. et al. Tackling antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 894–896 (2011).

Zaura, E. et al. Same exposure but two radically different responses to antibiotics: resilience of the salivary microbiome versus long-term microbial shifts in feces. mBio 6, e01693-15 (2015).

Lim, W. S. et al. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax 64 (Suppl. 3), iii1–iii55 (2009).

Freter, R. In vivo and in vitro antagonism of intestinal bacteria against Shigella flexneri: II. The inhibitory mechanism. J. Infect. Dis. 110, 38–46 (1962).

Mogayzel, P. J. Jr. et al. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation pulmonary guideline. Pharmacologic approaches to prevention and eradication of initial Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Ann. Am. Thorac Soc. 11, 1640–1650 (2014).

Smyth, A. R. & Walters, S. Prophylactic anti-staphylococcal antibiotics for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11, CD001912 (2014).

Langton Hewer, S. C. & Smyth, A. R. Antibiotic strategies for eradicating Pseudomonas aeruginosa in people with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11, CD004197 (2014).

Melnyk, A. H., Wong, A. & Kassen, R. The fitness costs of antibiotic resistance mutations. Evol. Appl. 8, 273–283 (2015).

Clarridge, J. E. III. Impact of 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis for identification of bacteria on clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17, 840–862 (2004).

Woo, P. C., Lau, S. K., Teng, J. L., Tse, H. & Yuen, K. Y. Then and now: use of 16S rDNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification and discovery of novel bacteria in clinical microbiology laboratories. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14, 908–934 (2008).

Janda, J. M. & Abbott, S. L. 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification in the diagnostic laboratory: pluses, perils, and pitfalls. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 2761–2764 (2007).

Koljalg, U. et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 22, 5271–5277 (2013).

Bosshard, P. P. Incubation of fungal cultures: how long is long enough? Mycoses 54, e539–e545 (2011).

Balajee, S. A. et al. Sequence-based identification of Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Mucorales species in the clinical mycology laboratory: where are we and where should we go from here? J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 877–884 (2009).

Hanage, W. P. et al. Using multilocus sequence data to define the pneumococcus. J. Bacteriol. 187, 6223–6230 (2005).

Vebø, H. C., Karlsson, M. K., Avershina, E., Finnby, L. & Rudi, K. Bead-beating artefacts in the Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes ratio of the human stool metagenome. J. Microbiol. Methods 129, 78–80 (2016).

Browne, H. P. et al. Culturing of 'unculturable' human microbiota reveals novel taxa and extensive sporulation. Nature 533, 543–546 (2016).

Linden, S. K., Sutton, P., Karlsson, N. G., Korolik, V. & McGuckin, M. A. Mucins in the mucosal barrier to infection. Mucosal Immunol. 1, 183–197 (2008).

Koser, C. U., Ellington, M. J. & Peacock, S. J. Whole-genome sequencing to control antimicrobial resistance. Trends Genet. 30, 401–407 (2014).

Punina, N. V., Makridakis, N. M., Remnev, M. A. & Topunov, A. F. Whole-genome sequencing targets drug-resistant bacterial infections. Hum. Genom. 9, 19 (2015).

Walker, T. M. et al. Whole-genome sequencing for prediction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug susceptibility and resistance: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 15, 1193–1202 (2015).

Bradley, P. et al. Rapid antibiotic-resistance predictions from genome sequence data for Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 6, 10063 (2015).

Winstanley, C. et al. Newly introduced genomic prophage islands are critical determinants of in vivo competitiveness in the Liverpool Epidemic Strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Genome Res. 19, 12–23 (2009).

Feehery, G. R. et al. A method for selectively enriching microbial DNA from contaminating vertebrate host DNA. PLoS ONE 8, e76096 (2013).

Fischer, N. et al. Evaluation of unbiased next-generation sequencing of RNA (RNA-seq) as a diagnostic method in influenza virus-positive respiratory samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 53, 2238–2250 (2015).

Coley, H. M. Mechanisms and strategies to overcome chemotherapy resistance in metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 34, 378–390 (2008).

Kupferschmidt, K. Resistance fighters. Science 352, 758–761 (2016).

Day, T. & Read, A. F. Does high-dose antimicrobial chemotherapy prevent the evolution of resistance? PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1004689 (2016).

Pena-Miller, R. et al. When the most potent combination of antibiotics selects for the greatest bacterial load: the smile-frown transition. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001540 (2013).

McArthur, A. G. et al. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 3348–3357 (2013).

Rubin, B. K. Pediatric aerosol therapy: new devices and new drugs. Respir. Care 56, 1411–1423 (2011).

Traini, D. & Young, P. M. Delivery of antibiotics to the respiratory tract: an update. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 6, 897–905 (2009).

Palmer, L. B. & Smaldone, G. C. Reduction of bacterial resistance with inhaled antibiotics in the intensive care unit. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 189, 1225–1233 (2014).

Ryan, G., Singh, M. & Dwan, K. Inhaled antibiotics for long-term therapy in cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, CD001021 (2011).

Quon, B. S., Goss, C. H. & Ramsey, B. W. Inhaled antibiotics for lower airway infections. Ann. Am. Thorac Soc. 11, 425–434 (2014).

Summers, W. C. Bacteriophage therapy. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55, 437–451 (2001).

Young, R. & Gill, J. J. Phage therapy redux — what is to be done? Science 350, 1163–1164 (2015).

Nobrega, F. L., Costa, A. R., Kluskens, L. D. & Azeredo, J. Revisiting phage therapy: new applications for old resources. Trends Microbiol. 23, 185–191 (2015).

Reyes, A., Wu, M., McNulty, N. P., Rohwer, F. L. & Gordon, J. I. Gnotobiotic mouse model of phage-bacterial host dynamics in the human gut. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20236–20241 (2013).

Servick, K. Beleaguered phage therapy trial presses on. Science 352, 1506 (2016).

Alemayehu, D. et al. Bacteriophages phiMR299-2 and phiNH-4 can eliminate Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the murine lung and on cystic fibrosis lung airway cells. mBio 3, e00029-12 (2012).

Debarbieux, L. et al. Bacteriophages can treat and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections. J. Infect. Dis. 201, 1096–1104 (2010).

He, X., McLean, J. S., Guo, L., Lux, R. & Shi, W. The social structure of microbial community involved in colonization resistance. ISME J. 8, 564–574 (2014).

Lawley, T. D. et al. Targeted restoration of the intestinal microbiota with a simple, defined bacteriotherapy resolves relapsing Clostridium difficile disease in mice. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002995 (2012).

Adamu, B. O. & Lawley, T. D. Bacteriotherapy for the treatment of intestinal dysbiosis caused by Clostridium difficile infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16, 596–601 (2013).

Gough, E., Shaikh, H. & Manges, A. R. Systematic review of intestinal microbiota transplantation (fecal bacteriotherapy) for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 53, 994–1002 (2011).

Colman, R. J. & Rubin, D. T. Fecal microbiota transplantation as therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crohns Colitis 8, 1569–1581 (2014).

Dickson, R. P., Martinez, F. J. & Huffnagle, G. B. The role of the microbiome in exacerbations of chronic lung diseases. Lancet 384, 691–702 (2014).

Conklin, L. et al. Systematic review of the effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine dosing schedules on vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease among young children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 33 (Suppl. 2), S109–S118 (2014).

Esposito, S. et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation in children and adolescents with asthma: impact of the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and evaluation of potential effect of thirteen-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. BMC Infect. Dis. 16, 12 (2016).

Hampton, L. M. et al. Prevention of antibiotic-nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae with conjugate vaccines. J. Infect. Dis. 205, 401–411 (2012).

Kyaw, M. H. et al. Effect of introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 1455–1463 (2006).

Ammann, A. J. et al. Polyvalent pneumococcal-polysaccharide immunization of patients with sickle-cell anemia and patients with splenectomy. N. Engl. J. Med. 297, 897–900 (1977).

Bou, R. et al. Prevalence of Haemophilus influenzae pharyngeal carriers in the school population of Catalonia. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 16, 521–526 (2000).

Lerman, S. J., Kucera, J. C. & Brunken, J. M. Nasopharyngeal carriage of antibiotic-resistant Haemophilus influenzae in healthy children. Pediatrics 64, 287–291 (1979).

Murphy, T. F. et al. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae as a pathogen in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 28, 43–48 (2009).

Dagan, R. & Klugman, K. P. Impact of conjugate pneumococcal vaccines on antibiotic resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8, 785–795 (2008).

Wilby, K. J. & Werry, D. A review of the effect of immunization programs on antimicrobial utilization. Vaccine 30, 6509–6514 (2012).

Leach, A. J. et al. Reduced middle ear infection with non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae, but not Streptococcus pneumoniae, after transition to 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable H. influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine. BMC Pediatr. 15, 162 (2015).

Simpson, J. L. et al. Airway dysbiosis: Haemophilus influenzae and Tropheryma in poorly controlled asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 47, 792–800 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. Airway microbiota in severe asthma and relationship to asthma severity and phenotypes. PLoS ONE 11, e0152724 (2016).

Johansen, H. K. & Gotzsche, P. C. Vaccines for preventing infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8, CD001399 (2015).

Maiden, M. C. Population genomics: diversity and virulence in the Neisseria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 467–471 (2008).

Rao, D., Webb, J. S. & Kjelleberg, S. Microbial colonization and competition on the marine alga Ulva australis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5547–5555 (2006).

Ley, R. E., Peterson, D. A. & Gordon, J. I. Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell 124, 837–848 (2006).

Comas, I. et al. Out-of-Africa migration and Neolithic coexpansion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with modern humans. Nat. Genet. 45, 1176–1182 (2013).

Walker, T. M. et al. Whole-genome sequencing to delineate Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreaks: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 137–146 (2013).

Snitkin, E. S. et al. Tracking a hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with whole-genome sequencing. Sci. Transl Med. 4, 148ra116 (2012).

LiPuma, J. J., Dasen, S. E., Nielson, D. W., Stern, R. C. & Stull, T. L. Person-to-person transmission of Pseudomonas cepacia between patients with cystic fibrosis. Lancet 336, 1094–1096 (1990).

Cheng, K. et al. Spread of β-lactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a cystic fibrosis clinic. Lancet 348, 639–642 (1996).

Bryant, J. M. et al. Whole-genome sequencing to identify transmission of Mycobacterium abscessus between patients with cystic fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 381, 1551–1560 (2013).

Bryant, J. M. et al. Emergence and spread of a human-transmissible multidrug-resistant nontuberculous mycobacterium. Science 354, 751–757 (2016).

Saiman, L. et al. Infection prevention and control guideline for cystic fibrosis: 2013 update. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 35 (Suppl. 1), S1–S67 (2014).

Chotirmall, S. H. & McElvaney, N. G. Fungi in the cystic fibrosis lung: bystanders or pathogens? Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 52, 161–173 (2014).

Parize, P. et al. Impact of Scedosporium apiospermum complex seroprevalence in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 13, 667–673 (2014).

Larkin, E. et al. The emerging pathogen Candida auris: growth phenotype, virulence factors, activity of antifungals, and effect of SCY-078, a novel glucan synthesis inhibitor, on growth morphology and biofilm formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e02396-16 (2017).

de Wit, R. & Bouvier, T. 'Everything is everywhere, but, the environment selects'; what did Baas Becking and Beijerinck really say? Environ. Microbiol. 8, 755–758 (2006).

Byrd, A. L. & Segre, J. A. Infectious disease. Adapting Koch's postulates. Science 351, 224–226 (2016).

Acknowledgements

W.O.C.M.C., M.J.C. and M.F.M. receive funding from the Wellcome Trust and from the Asmarley Trust. W.O.C.M.C. and M.F.M. are joint Wellcome Senior Investigators. W.O.C.M.C. also received funding for microbiome studies with a Senior Investigator award from the National Institute for Health Research, United Kingdom.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.O.C.M.C. carried out research, wrote the article and contributed to discussions, review and editing of the manuscript. M.J.C. and M.F.M. carried out research and contributed to discussions, review and editing of the manuscript. The authors gratefully acknowledge the considerable input of two anonymous reviewers.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cookson, W., Cox, M. & Moffatt, M. New opportunities for managing acute and chronic lung infections. Nat Rev Microbiol 16, 111–120 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.122

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.122

This article is cited by

-

Microrobots for pulmonary drug delivery

Nature Reviews Bioengineering (2026)

-

YouTube and TikTok as sources of information on acute pancreatitis: a content and quality analysis

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

Limited value of Nanopore adaptive sampling in a long-read metagenomic profiling workflow of clinical sputum samples

BMC Medical Genomics (2025)

-

Antimicrobial peptide delivery to lung as peptibody mRNA in anti-inflammatory lipids treats multidrug-resistant bacterial pneumonia

Nature Biotechnology (2025)

-

Molecular probes for in vivo optical imaging of immune cells

Nature Biomedical Engineering (2025)